On April 12, as part of the monthlong Carnegie Nexus series, Becoming Migrant, Carnegie Museums is partnering with The Documentary Works and its founder, photographer and activist Brian Cohen, on a presentation of compelling photographs and the stories behind them culled from the project Out of Many: Stories of Migration. The images are part of the current exhibition, Emigration-Immigration-Migration: Five Photographic Perspectives, on view at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, which documents generations of immigrants and their descendants. To follow is an excerpt from an essay that first appeared in the Out of Many catalogue, along with images from the project.

——–

While other cities became magnets for immigrants from Asia and Latin America in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, Pittsburgh did not. By the end of the 20th century, only about one in 25 people in the city had been born outside of the country.

While its numbers are still lower than the rest of the country’s, Pittsburgh is now attracting more immigrants. Its foreign-born population grew 32 percent from 2000 to 2015. (In Allegheny County, the number was 40 percent.) About one in three immigrants have come since 2010. Just over half are from Asia, around one in four are from Europe, 10 percent are from Latin America, and 9 percent are from Africa.

New citizens, the Mirza family from Pakistan (left to right): Laiba, Mohid, Raqna, Muhab (front), and Naeem. Naeem has been in the United States for 18 years. His first visit was in 1999. His company transferred him permanently in 2001. The Mirza children typically dress in American attire. Originally from the flat, hot, dry part of Pakistan, the family stands outside in the first snow of the season. Photo: Lynn Johnson

The reason: there are jobs here now. It’s relatively safe, housing is relatively affordable, schools are relatively decent. And the region’s immigrants, including many who are undocumented, are once again contributing to the local economy.

The thousands of immigrants who are now in Pittsburgh include many who have come as refugees. The U.S. refugee program is administered through the Department of State, and is part of a worldwide effort through the United Nations to help some of the 65 million people who have been forcibly displaced from their homes. The United States has been accepting about 85,000 annually in recent years, though President Donald Trump has lowered that number by half. About 500 refugees a year are placed in Pittsburgh, one of about 200 cities and towns in the United States that accept them. Refugees are eligible for permanent residency in the United States; after five years, they are eligible to become U.S. citizens.

New citizens from multiple nations raise their hands in pledge to America during a naturalization ceremony this past fall in the federal courthouse in Pittsburgh. Photo: Lynn Johnson

They come from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Congo. From Somalia and Myanmar. Nepali speakers from Bhutan and Meskhetian Turks from Russia. Some were forced into the army. Or their families have lived in refugee camps for generations. They cannot go back to where they are from.

When they first descend the escalator at Pittsburgh International Airport, they are greeted by a refugee officer from a local agency. Some come with massive suitcases. Some come with just a small bag and the clothes on their back. The agencies help the refugees for three months; they place them in housing and pay rent on their apartment, help them pay for utilities, bus passes, and food.

Dua Zeglam, Khalid Azzouz, and their two children Zizo, 3, and Zayd, 3 months, from Tripoli, Libya. Professionals, the couple has lived in the United States since 2012. Originally they settled in Ohio but are now in Morgantown, W.Va. “It’s a relief to have another home. We feel welcome here,” said Dua. But the process of becoming a citizen was long and expensive. Photo: Lynn Johnson

They also help translate modern American life to them. The money to do all this comes from the federal government. But three months go by quickly; after that, apart from Medicaid and food stamps, which are available to all eligible citizens and legal immigrants in the United States, the refugees are on their own.

Bahati Kasongo came into Pittsburgh at night, after taking four planes across three continents to get here. There was snow on the ground. She’d never seen snow.

Bahati Kasongo with her daughter, Atifa. Photo: Brian Cohen

She came with her two sisters; they were placed in an apartment in a housing complex in the West End. Other Africans had warned her: “The Americans are mean. They don’t like Africans.” But, she said, she wouldn’t just take their word for it. “I decided not to believe it before I saw it with my own eyes. I told my sisters: ‘Don’t be afraid.'” Some kids took the clothes off her drying line and dumped them on the hillside behind her apartment. But that only happened once, and she harbors no ill will.

She has heard gunshots near her home. The pastor at her church says don’t be afraid. Americans won’t go after you unless you provoke them. There are so many things to learn. She initially was told her daughter, Atifa, wasn’t old enough for school. But she’s trying to figure out how to get her into the preschool that is down the hill from her apartment. There are forms to fill out and countless administrative boxes to check. The agency that placed her was able to help her secure the basics of food and housing. But there are many other things they simply didn’t have time to help her with, and now she is figuring these things out on her own, in a foreign language.

Back in Burundi, where she lived after leaving the Congo several years ago, there was the lake, Tanganyika. There was singing in her church choir, in Swahili, in French, in Kirundi, in Lingala, in English. Her English is passable, but limited. A few months into her life as an American, she understands more than she can speak. Her father is in Tampa now, but she doesn’t have enough money to visit him. She takes two buses to get to her job washing dishes at a restaurant in Robinson Township. She works, comes home, takes care of Atifa, calls her husband back home in Burundi. She is trying to get him to come to the United States. Would she ever want to go back to Africa? “No,” she says. It’s too dangerous. “Je vais chercher la vie ici.” I’m going to find my life here.

The Undocumented

Some undocumented Latinos in Pittsburgh worry more about deportation since the election of Donald Trump. They have stopped going to parks. Husbands and wives have stopped driving in cars together, so that if one gets stopped and deported, the other will be able to stay and take care of their children. They look outside their apartments to make sure Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents aren’t waiting there before sending their kids to school. They have become a community in hiding.

Gisela came to the United States 13 years ago, from Acapulco, where the drug gangs were brutalizing each other and terrorizing the populace. Her oldest son, Oscar, was born in Mexico, and is undocumented. He is a senior in high school, and wants to go to college. Her two younger children, Felipe, age 11, and Migdalia, 13, are U.S. citizens.

Gisela and her husband, Ricardo, work in kitchens. They pay taxes and rent. They make sure the kids’ homework gets done. They don’t see returning to Acapulco as much of an option: when Gisela’s brother-in-law returned to Mexico, a gang immediately threatened to kill his family if he didn’t pay a $10,000 ransom.

Single father Jose Luis Ibarra of Mexico flanked by daughters Brianna and Emma. The family lives in Brookline. Photo: Nate Guidry

After the 2016 election, Felipe asked Gisela if it was true they’d have to live in Mexico. His teacher had told the class that if Trump won, all the Mexicans would have to go home. “I wish this was something the kids didn’t have to worry about. This is something that grown-ups should have to worry about, not kids,” she said. She told him that if they get deported, they won’t be broken up. They will stay together, and go to Mexico. They would be juntos, together. But her children are more American than anything, she says. “They are used to living here,” she says. “They think they are of this country.” Which, of course, they are.

Making a Home in America

In many ways, it was a standard suburban life: three kids in school, both parents working, sports, activities, church on Sunday. But Elizabeth and Sebastian Gnalian knew their children lived in two worlds. Inside the house, they spoke Malayalam, the official language of the southern Indian state of Kerala, and ate Indian food. Outside the house, they lived as Americans. The kids went to student council meetings and played sports. They spoke English. “When I go to work, I am not Indian at all,” Elizabeth says.

Elizabeth came to Pittsburgh in 1985; Sebastian followed her in 1991, a few years after they married in India. Both pursued graduate degrees and got professional jobs, and bought a small home in the suburb of McCandless. Yet they knew some would not accept them in their adopted home.

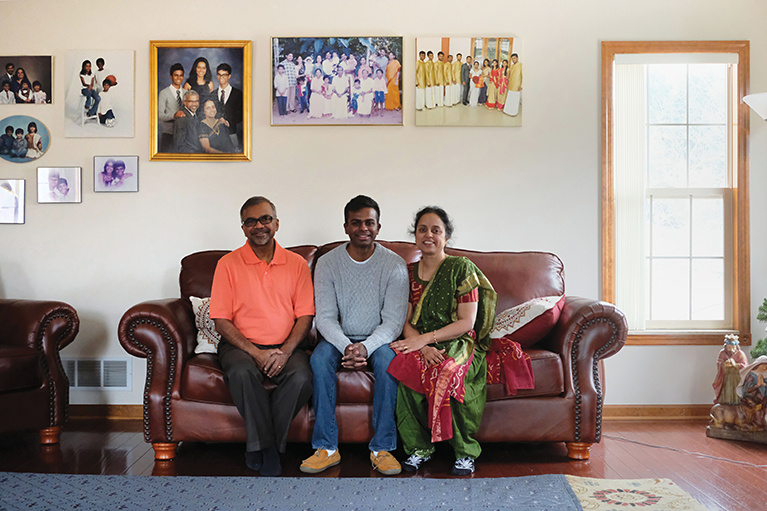

Sebastian, Antony, and Elizabeth Gnalian. Photo Brian Cohen

Sometimes Elizabeth’s patients would object to her taking care of them. “Why are you here?” they would say. “Go back to your country.” When that happened, she would fetch a co-worker. “I would say ‘I’m a nurse, I’m here to comfort you, and if you’re not comfortable that’s okay, I’ll send someone else,'” she says. She trained herself not to take it personally.

In some ways, the Gnalians were used to trying not to take these everyday slights to heart. The Gnalians are Indian Catholics from the southern state of Kerala. India’s Christian community dates to St. Thomas the Apostle in the first century. Christians in India are a minority, and occupy an outsider position in their society similar in some ways to being Indian in America.

“That minority feeling never left me,” Sebastian says. “It is not a first-time, raw, stinging experience,” Elizabeth says. In South India, Elizabeth says, some Brahmins would not touch the hand of a Christian, believing them “untouchable.” When a Christian entered the room of a Brahmin, the Brahmins would step back.

Sebastian, a soft-spoken man, felt completely at home among his co-workers. He remembers how his boss drove him to the hospital when one of his children was born and he was without a car. But sometimes in public, he could feel the eyes of people on him, as if to ask “why are you here?”

“You almost wanted to distance yourself from your own heritage because you didn’t want to be the ‘other.’” – Antony Gnalian

These feelings were magnified in the months after 9/11. Sebastian went out and bought tiny American flags, and stuck them in his front yard. He thought of them as demonstrations of sympathy that he wanted to show his neighbors. “I wanted to make sure they understood that what happened affected all of us,” he says.

The couple’s middle child, Antony, was 7 at the time. He was one of the few brown kids at his school. His classmates made terrorist jokes, and he would laugh along. Later on, he began to suspect the kids were also laughing at him. Antony remembers feeling uncomfortable when his dad blared Indian folk music on the speakers of the family car. “You almost wanted to distance yourself from your own heritage because you didn’t want to be the ‘other,'” he says.

But being the “other” is at times unavoidable. In some ways, the election of Donald Trump-and the anti-immigrant sentiment surrounding it-has made these feelings more intense for the Gnalians. In February 2017, a white man shot and killed two Indian software engineers in a Kansas bar, after questioning them about their immigration status. A week later, as Antony was going out to meet a friend at a bar, Sebastian and Elizabeth quizzed him on where he was going.

“There was a lot of fear in my father’s eyes, and my mother’s eyes,” Antony says. They wanted him to be careful. It’s something he’s learning to do-he doesn’t go to bars outside of the city. He doesn’t want to be vulnerable. At the same time, he doesn’t want to live in fear.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Community