You May Also Like

Reimagining Landscapes Opening up the World for Others Progress in the Pop DistrictRising from the absolutist politics of the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation, Europe’s Age of Enlightenment sparked a seismic shift in thinking and, subsequently, a dramatically different way of doing things. Big things like fighting revolutions, establishing representative governments, abolishing slavery, and educating women.

During its heyday in the 1700s, the Enlightenment was the domain of serious scholars and deep thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Isaac Newton, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Voltaire. It ultimately gained a firm foothold in the colonies as founding fathers Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington adopted its doctrines to help fuel the American Revolution and form a more perfect union.

As the people of Europe began looking forward with a heightened sense of optimism and purpose, says Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts at Carnegie Museum of Art, they also began looking for inspiration. For Lippincott, that raised the question: Where did those inspired ideas come from?

Lippincott found some answers in the museum’s extensive holdings from 1750–1850. From here, an exhibition was born.

Ary Scheffer, Dante and Virgil Encountering the Shades of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta in the Underworld (detail), 1851, Heinz Family Fund and anonymous gift

In Visions of Order and Chaos: The Enlightened Eye, on view March 3 through June 24 in the Heinz Galleries, the museum features artists’ visions of an 18th-century world rapidly becoming modern, shaped by fierce debates about the role of religion in public life, the distribution of wealth, a woman’s place in society, and the value of public education. The exhibition will feature paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings, furniture, and personal objects such as fans and miniatures. Some of them will be on view for the first time. Others are already popular with museumgoers, including the utopian view of a young United States in Edward Hicks’ 1837 painting, The Peaceable Kingdom, which depicts European colonists, Native Americans, and the animal world all coexisting peacefully.

Lippincott’s years-long quest to develop the show began when she descended into the bowels of the museum to survey its vast collections.

“It was wonderful to rummage through the basement and discover a great many important portraits that haven’t been on view here for 50 to 75 years,” she recounts. Several of those finds were in great need of conservation and cleaning to restore them to their original brilliance, such as an 8-foot-tall portrait by Scottish painter Henry Raeburn.

“It is absolutely a commentary on our times, and as every day passes it becomes more and more relevant.” – Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts at Carnegie Museum of Art

Removing decades of “Pittsburgh atmosphere,” as Lippincott refers to the layers of dirt and grime that accumulated in pre-climate-controlled museum environments, is a painstaking process that museum conservators applied to six paintings. With more than 200 works in all, the exhibition reflects an important and fascinating period in history, while also having something to say about the here and now.

Mary Darly, Matthew Darly, Bunker’s Hill and Cupid’s Tower, 1776, Howard N. Eavenson Memorial Fund

“It is absolutely a commentary on our times,” Lippincott says, “and as every day passes it becomes more and more relevant. There’s been a lot of talk and thinking and writing today about where the United States is going and where we fit in the world. Those were exactly the questions that were being asked here during the revolution and the creation of the United States. And they’re still really important questions.”

When the pendulum swings

The Enlightenment was a time of reason and order. But the quest for perfection did not always result in happy endings. The French Revolution, inspired by ideals of liberty and equality, quickly devolved into a Reign of Terror that resulted in 300,000 arrests and some 17,000 official executions.

By the end of the 18th century, the Enlightenment was waning. Feeling more, thinking less was rapidly becoming the preferred approach to life, politics, and art. Dubbed Romanticism, this backlash movement, Lippincott says, “can be interpreted as a pessimistic withdrawal from global optimism and a retreat into one’s interior world.”

Reason gave way to emotion, the collective conscience to individualism, the power of science to the poetry of nature. Certainly, the principles and attributes associated with the Enlightenment and Romanticism are not mutually exclusive. Nor are they intrinsically good or bad. But each era illustrates how the pendulum can swing far to one side, and back again. “The view of history that emerges,” Lippincott says, “is cyclical.”

Jean-Frederic Bosset, Miniature Portrait of Madame Jeanne Jacquelin Therese Vimont Bellon Depont (or De Pont), 1808, Gift of Herbert DuPuy

The exhibition provides a broad view through art. “We’re presenting a continuum,” she explains. “There will be images that some people will find exciting, interesting, and stimulating and other people will find terrifying or awful. We go from the extreme of rational order to the extreme of chaos. Certain parts of the show are going to make people uncomfortable and certain parts are going to have them laughing or giggling or recognizing themselves.”

As visitors catch glimpses of their 21st-century personas in 18th-century art, they’ll be asked to consider whether or not humans are perfectible. The query itself seems to prompt a sense of inevitability.

“While our technology and our culture have changed,” Lippincott says, “human nature hasn’t, and the Enlightenment’s understanding of that is very modern.”

Enter the portrait. It is, in essence, today’s selfie-the face we choose to share with the world. Hardly as instantaneous as a picture captured on a smartphone, formal portraits required a certain thoughtfulness. And that’s what makes the Miniature Portrait of Madame Jeanne Jacquelin Therese Vimont Bellon Depont (or De Pont) so beguiling.

Her gentle smile suggests an air of contentment. But not so fast. Nestled between the watercolor and the frame, researchers discovered two locks of hair-one blonde, one dark-and a playing card with hearts and the French word for lover (amante) on it. These tokens were, and still are, hidden away. Her public façade seems to belie the reality of her life.

“While our technology and our culture have changed, human nature hasn’t, and the Enlightenment’s understanding of that is very modern.”

– Louise Lippincott, curator of fine arts at Carnegie Museum of Art

And as far as Lippincott is concerned, ornate 18th-century fans, made of ivory, mother of pearl, and swanskin, were the Snapchat of their day. “The way you held, positioned, and moved your fan sent signals across the room to people you wanted to communicate with,” she explains.

Artist unknown, Fan, c. 1723–1774, Gift of Herbert DuPuy

She’s talking about secret messages sent to admirers to arrange clandestine rendezvous. The code was simple for those in the know; displaying three folds meant meet me at 3 o’clock, for example. But a quick flick of the wrist could erase the entire exchange from prying eyes, such as your mother-in-law’s.

As it turns out, 300-year-old fans and today’s smartphones have something in common. “They’re both small, portable, luxury objects whose decorations reflect something important about your character, personality, and tastes,” says Lippincott.

Now and forever

These days, there’s much debate about the parallels that can be drawn between the United States and the Roman Empire. It’s both a logical and emotional connection to make, especially since our country was founded during the Enlightenment and based, at least in part, on the Roman Republic.

The exhibition doesn’t provide an answer, but it does offer some perspective on the symbols of power and the costs of war. “We have some really gut-wrenching stuff here,” Lippincott says.

Perhaps most evocative are Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Camera Sepolcrale (Funerial Chamber) showing Rome in ruins and Francisco de Goya’s image of bayonet combat from his Disasters of War series.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Camera Sepolcrale (Funerial Chamber), c.1750s, Charles J. Rosenbloom Fund

Less visceral but no less engaging is a series of portraits. What makes these images even more intriguing is how they’ll be presented. Taking a less traditional approach to art interpretation, Lippincott opted to group them together to encourage people to look at them closely and compare and contrast.

Visitors will find three versions of George Washington: the revolutionary, the hero, and the president; France’s King Louis XVI seeking to hold on to power; a Greek revolutionary leader trying to gain support for his cause; and a Native American chief striving to rally public opinion against western expansion.

“When you line these all up,” Lippincott says, “you can see that they’re all in the same pose and they’re all trying to make the same point. These are images of embattled leaders at a moment when the future of their cause is not clear.

“It’s political propaganda, and it hasn’t changed much.”

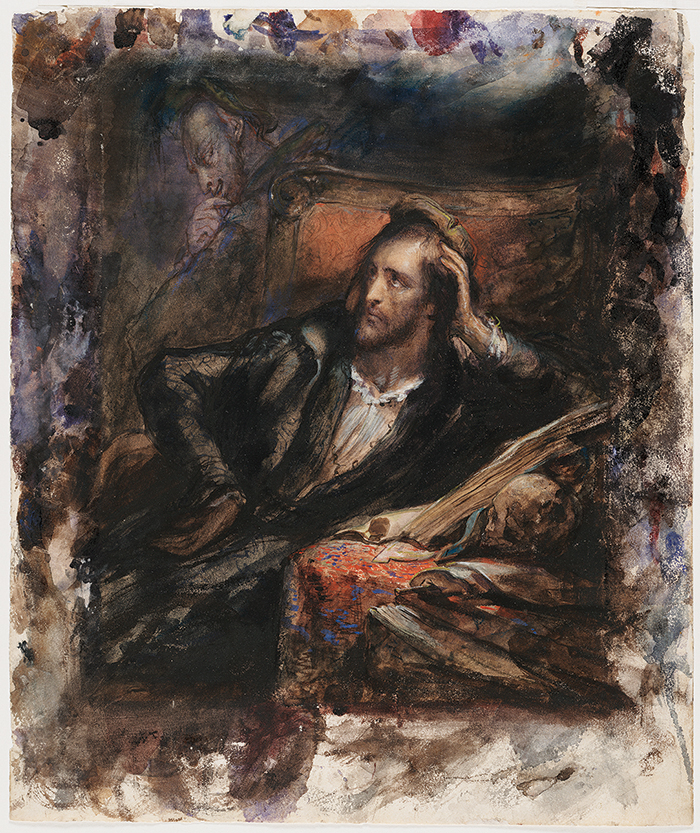

Ary Scheffer, Faust in His Study, c. 1831, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Daniel Fishkoff

It’s about politics, power, and public relations-and every era has its own rules of engagement and social conventions. Sure, the mediums change throughout time-from formal portraits to digital avatars, from 1,400-word speeches to 140-character tweets-but the purposefulness behind the message remains timeless.

So, how best to describe the 21st-century sensibility? Order or chaos?

Lippincott leaves museumgoers to ponder a quote from another enlightened founding father, Thomas Paine: “We have the power to build the world anew.”

His words are, Lippincott says, “political, philosophical, optimistic, and quintessentially American.”

Generous support for Visions of Order and Chaos: The Enlightened Eye is provided by The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art, the Richard C. von Hess Foundation, Mary Louise and Henry J. Gailliot, and Ritchie Battle. Additional support is provided by the Mary Louise and Henry J. Gailliot Fund for Exhibitions, the Martin G. McGuinn Art Exhibition Fund, Martha Malinzak, and The European Fine Art Foundation.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art