Inside The Andy Warhol Museum’s studio, 8-year-old Nyeila Ferguson uses a squeegee to drag pink paint across a screen. A few minutes later, she stares in astonishment at the finished product-she and her dad smiling radiantly, shoulder to shoulder. It’s like magic, this way of immortalizing her father, Walter, almost two years after he died of a heart attack.

“It’s amazing and awesome,” she says, her brown eyes widening. “I don’t know how they got the picture of my dad and me on the screen. Can I make a thousand?”

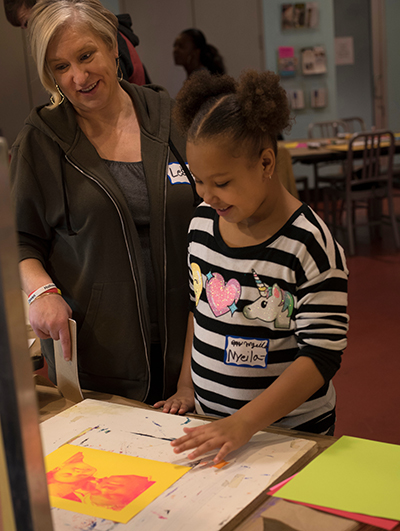

Nyeila Ferguson tries her hand at silkscreening with help from artist-educator Paul O’Brien.

The third-grader from Penn Hills couldn’t make quite that many images during a three-hour tour and silkscreening workshop on a recent Saturday morning. But she did personalize more than a dozen prints in various color combinations-a kaleidoscope of paternal love. She also printed a turquoise version of the image on a pink T-shirt-it’s a way to keep her dad closer. Pointing to her stack, she says, “It means a lot to me. I will keep them forever, so I can show my kids.”

Four times a year, artist-educators at The Warhol guide a small group of Caring Place youth through the process of making silkscreen prints of cherished photographs of their deceased family members. The activity gives young people a creative way to express their grief and talk about their loss, a subject often too uncomfortable for many people to broach with kids.

Kenyh Taylor’s personalized silkscreen print of her with her late father, Kenneth.

“It’s like spending an hour or two with Mom or Dad,” says Andrea Lurier, a psychologist and program manager of Highmark Caring Place. “The kids aren’t just making art; they are making memories. It’s beautiful to watch the moment when the first print comes up.”

Nyeila Ferguson and her mother, Lesley Mallon, watch as Nyeila’s first print is revealed.

The kids make silkscreens the same way that Pop Art pioneer Andy Warhol churned out his famous portraits, one after another, in his legendary studio, The Factory, in New York City. Today, those iconic images hang in his museum, a glitterati of Marilyn, Jackie, and Elvis, alongside intimate portraits of his mother, Julia.

“The kids aren’t just making art; they are making memories. It’s beautiful to watch the moment when the first print comes up.”

– Andrea Lurier, program manager of Highmark Caring Place

As part of the experience, the families learn about a more personal and softer side of Warhol, who was widely known for his rebellious spirit and wild parties with hip celebrities. Leading the group on a private tour of the museum, Donald Warhola, the late artist’s nephew, shares his uncle’s own experience with grief. Warhol’s father, Andrej Warhola, a Carpatho-Rusyn immigrant from present day eastern Slovakia who worked in construction, died when Andy was 13 years old. The loss devastated the family. Soon after, his mother was hospitalized for colon cancer. “How scary, to lose your father and then worry about your mother,” Donald says as he leads the group through the museum’s seventh floor, which is dedicated to the artist’s early years.

Kenyh Taylor, and her mother, Jamira Taylor, try applying gold leaf to artwork at The Andy Warhol Museum.

Julia survived the cancer, and Andy, who was a notoriously sickly kid, had a close relationship with her throughout his life. “She was really the most influential person in his life,” says Donald, explaining to the families that when a young Warhol had bouts of illness brought on by a neurological disorder, it was Julia who helped him develop his interest in art, sharing her love of drawing and folk-craft traditions of the Carpatho-Rusyn culture. In 1952, she moved in with Andy in New York, where he became a successful commercial artist and eventually a Pop Art superstar. Julia’s hand is seen in her son’s art, as her distinct, decorative handwriting graces many of his drawings, album covers, and book illustrations. In 1957, he published a book of her drawings, Holy Cats by Andy Warhol’s Mother.

Donald Warhola giving a tour of the museum

with a photograph of “Uncle Andy” in the background.

“It’s amazing to witness the kids lose themselves in the process in a meaningful way—they vent and grieve and create in a way that Andy found solace.”

– Donald Warhola, nephew of Andy Warhol

Donald recalls that as an adult, Andy, just like Julia, would kneel on the floor in the morning and say a prayer, asking God to bring him back home alive. “My dad did it, too,” says Donald. “Bubba had a saying in Slovak about the preciousness of life. That it’s on a thread.” Bubba is what Donald and the other grandchildren lovingly call Julia.

When she died in 1972, Andy was so overcome with grief that he couldn’t go to her funeral. “He wanted to go,” Donald explains. “But everyone deals with grief in different ways.”

Art that’s good for you

On the fifth floor of the museum, hanging alongside portraits of glamorous celebrities, is a pair of paintings of Julia Warhola in an apron, peering through her glasses. Created two years after her death, one portrait is in blue and green, while its double is in cheerier shades of red and purple. Warhol used his fingertips, rather than brushes or other tools, to apply paint on the canvases, providing an uncommon intimacy and abstract quality. Pointing to the images, Donald says, “She was his icon, his celebrity, his rock star. Of all the photos he could have used, he chose to depict her as a mom and grandmother and his primary support system,” Donald continues, describing the source photo as the “classic Bubba photo.”

Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, 1974, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

If his uncle were still alive, he would love seeing young people honoring their parents in the same way, Donald tells the group. “I know Uncle Andy would love this project.”

Before the youth begin a form of stenciling known as silkscreening, Paul O’Brien, museum artist-educator and studio programs coordinator, tells the families that he conceived of the workshop five years ago while he was missing his own mother, who had died about a decade earlier. He had been looking longingly at a giant white leather wedding album of his parents, wishing he could keep it as a cherished heirloom. But as one of 10 children, he knew he couldn’t just take it home. “There were a lot of hands on it,” says O’Brien.

He decided to multiply those memories in a very Warholian way-by reproducing the contents of the album as silkscreened images, the vibrant splashes of red, blue, yellow, and other colorful paints modernizing the vintage photographs. He gave a copy to each of his siblings for Christmas. “I made multiples that were almost the same but a little different,” says O’Brien. “Each one is a treasure. By reproducing the wedding album, I realized that it took a lot of pressure off the original album. It’s just as dear as it ever was, but it’s no longer this sacred relic.”

O’Brien found the time he spent with the album meaningful in and of itself, an experience he wanted for others.

“In art education, all the conversations are about how art is good for you, how art is good for the soul,” he says. “Day in and day out, you don’t get to see it with the same immediacy as you do in this project. With this experience you can really help ease some of the weight for these young people.”

In this way, it’s not unlike the art programs the museum hosts to help students on the autism spectrum identify facial expressions, body language, and social cues.

Looking Forward

A week before each workshop, participating kids share one of their favorite photos of their deceased loved one with The Warhol. O’Brien then makes screens of the images so the youth can come in on Saturday morning and start printing.

To make the screens, O’Brien burns film positives onto mesh fabric coated with a light-sensitive emulsion, which hardens under an exposure lamp, creating a photographic stencil. “The color brings it into today,” he says. “The photographs are about the past. With printing and colors, it makes them contemporary.”

There’s an art to making a silkscreen image of a photo so the nuances aren’t lost when gray tones are reduced to black and white. O’Brien wanted to make sure he caught the essence of each person-a shadow, the thickness of their eyebrows, the tilt of the head. He felt a heavy responsibility to make sure he did justice to a child’s cherished memory.

“Did I turn their parents into strangers?” he asks Lurier at one point during the workshop. “No, you consistently do well,” she responds. The true answer came in the joy on 8-year-old Nyeila’s face as she made her first print.

“It makes me smile to see her happy and doing something with her father and keeping his memory alive.” – Lesley Mallon

Unlike more boisterous activities hosted by Highmark Caring Place, this workshop is somewhat subdued, with children murmuring quietly with their parents as they examine the images. But as the morning progresses and they see their finished silkscreens, the kids start to talk more, laugh, and reminisce, especially as they cut hearts out of construction paper and add borders around their prints, applying watercolor and gold leaf as Warhol often did to his blotted-line drawings.

Kenyh Taylor in the Silver Clouds gallery.

“It’s amazing to witness the kids lose themselves in the process in a meaningful way-they vent and grieve and create in a way that Andy found solace,” says Donald.

The kids take a short break from printmaking and immerse themselves in the Silver Clouds gallery filled with Andy’s pillow-shaped Mylar balloons. “Art doesn’t have to be on the wall,” Donald tells the group. “You can experience and touch it. Let the clouds come to you.”

Nyeila bounces up and down, pushing the Silver Clouds through the air. But she can’t wait to get back to the studio to make more prints of her father.

“She could do this all day,” says her mother, Lesley Mallon. “This is up her alley. It makes me smile to see her happy and doing something with her father and keeping his memory alive.”

Nyeila likes to talk about the man who would run with her at the playground and who loved roses. “It keeps him in my memory,” she says. “I don’t talk to my friends about it.” That’s one reason she likes going to Highmark Caring Place. She loves painting and doing other projects that help her grieve. She gets to talk to other children who understand what she’s going through. The youth at the Caring Place work together to make a quilt of remembrance-each square represents a family member. The finished quilts are hung on the walls at the nonprofit’s main office on Stanwix Street in downtown Pittsburgh.

Ian Gallagher at The Andy Warhol Museum.

As the workshop comes to a close, Nyeila is happy that she gets to take her prints-her new memories-home with her. She wishes she could make more. “I wish I owned this place,” she says. Her mother laughs.

“What are we going to do to celebrate his birthday this year?” she asks her mother. They bat ideas back and forth before Nyeila announces a plan to remember her dad’s birthday with a bonfire in the backyard. “All the kids will jump on the trampoline with me,” she says.

Seventeen-year-old Ian Gallagher of Crafton is leaving with his own small stack of prints, including an image of his father, Peter, on the cover of a sketchbook where he draws tattoo designs. Ian says people get nervous when he brings up his father, who died of a heart attack last December. “It makes people uncomfortable,” he says.

“I usually deal with it myself.” This worries his mother, Lyllian Rose, who is concerned that Ian doesn’t talk about his grief. She thinks programs like this help him to remember and honor his father. “It was cool,” says Ian. “I like museums. “I don’t have that many photos of him. It’s nice to be able to put his photo on something. I’ll probably keep these prints forever.”