For nearly 60 years, Carnegie Museum of Natural History researchers have risen with the morning mists to string hundreds of feet of netting along the grounds of Powdermill Nature Reserve, the museum’s environmental research center in Rector, Pennsylvania. Their goal? To snatch as many birds out of the sky as possible.

While this may sound like the actions of a super villain, the procedure is the basis for one of the longest continuously running studies in the Western Hemisphere. Some 15,000 birds safely find their way into these nets annually-American goldfinches and magnolia warblers as well as sharp-shinned hawks, northern saw-whet owls, and yellow-bellied sapsuckers. They spend as little as 20 minutes in captivity before being released back into the wild, but the information they leave behind is priceless.

Lucas DeGroote removes a bird caught in a mist net at Powdermill Nature Reserve. Photo Pam Curtin

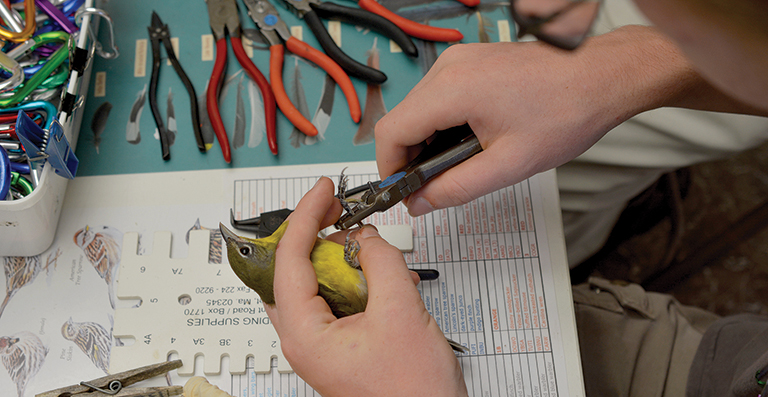

DeGroote bands a bird.

A cerulean warbler

That’s because even the most common of birds can be crucial indicators of change in an ecosystem. And while most people might not notice the teensy shifts occurring among the tiny, feathered dinosaurs scrapping for seed on their backyard birdfeeders, scientists like Lucas DeGroote can find patterns in all of those decades’ worth of capture data.

“We see many birds adapting, and that can give us hope. But with some species not keeping up with earlier springs, it also shows us that there’s reason to be concerned. There are sometimes limits to adaptation.”

– Lucas DeGroote, avian researcher at Powdermill Nature Reserve

In a study published in the journal Global Change Biology in 2016, DeGroote and fellow Carnegie Museum researcher Molly McDermott recounted their quest to find out if birds were altering their life cycles in response to climate change. The pair looked at more than half a century’s worth of capture data for 21 species of passerines, more commonly known as songbirds. Interestingly, the researchers found that 13 of these species now hatch their young earlier in the year, with eight of those species showing advancements of more than three days per decade. Three days might not seem like that big a deal, but when you consider that records go back as far as the 1960s, we’re actually talking about a change of more than two weeks.

“So, if you’re watching the birds in your backyard, you’ll see them showing up earlier than they once did and certainly nesting a lot earlier than they once did,” says DeGroote.

As to whether all of this is good or bad, DeGroote says it’s complicated.

Some of the species seemed to be thriving under the new conditions, including the eastern phoebe, red-eyed vireo, black-capped chickadee, and indigo bunting. In turn, others such as the cedar waxwing, American goldfinch, and hooded warbler showed decreased productivity as springs warmed. Another one of DeGroote’s studies, which is currently in peer review, suggests that the range for one species has been marching steadily northwest each decade, apparently as the birds follow the temperatures, foods, and nesting conditions they have evolved with.

“We see many birds adapting, and that can give us hope. But with some species not keeping up with earlier springs, it also shows us that there’s reason to be concerned,” says DeGroote. “There are sometimes limits to adaptation.”

The wisdom of trees

Birds aren’t the only organisms taking note of the warming world, of course. We can also find nuance in the world of plants.

For example, if you had gone to Squaw Run in Fox Chapel last April 27, you would have been greeted by a dense understory of head-high spicebush shrubs just beginning to pop with glossy red berries. If you could time travel back to the very same spot in the spring of 1900, the scene would look quite different. That year, the spicebush shrubs had just begun to produce flowers by late April, and it would be another few weeks before leaves and then fruit emerged.

We know this because Carnegie Museum of Natural History has its own time machine, of sorts. It’s called a herbarium, and it contains more than half a million plant specimens from as far back as 1754.

Collection manager Bonnie Isaac and fellow botanist Mason Heberling have been scouring the herbarium’s cabinets for specimens they can use to create a side-by-side view into the past. The botanists hope to show how plant life has adapted to a warming world simply by showing how early each species emerges from its winter slumber.

“Even though we’ve been studying the plants around here for decades or centuries, we still don’t know some of the basic information about our really common plants,” says Isaac.

As with birds, the botanists believe the differences will vary among species, and some of the examples they currently have on display in the museum’s We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene exhibition are striking.

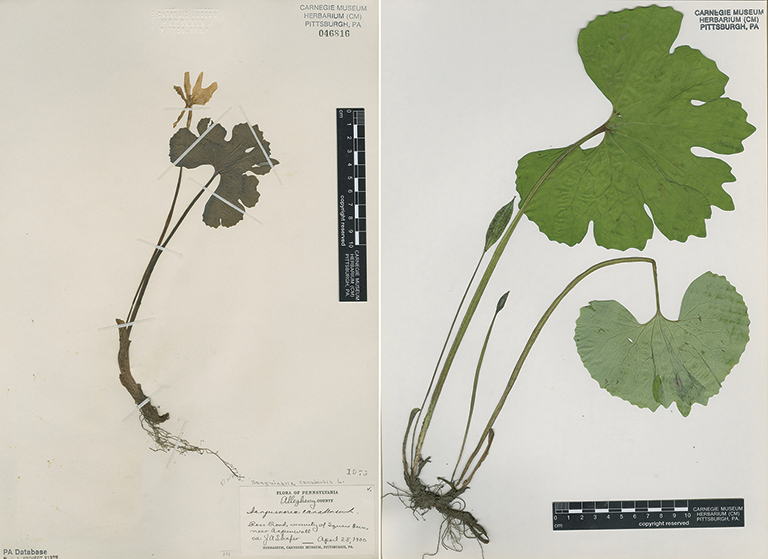

A bloodroot plant from O’Hara Township on April 24, 1905, and on the same day and location in 2017.

Botanist Bonnie Isaac (center) in the field.

Take bloodroot, a plant that typically produces large, fan-like leaves that keep close to the ground. On April 24, 1905, the bloodroot plants in Powers Run, O’Hara Township, sported leaves no bigger than a fist, with long, white and yellow flowers erupting up the middle. But on the very same day 112 years later, the Powers Run bloodroots had already shed their bouquets and the leaves had spread out as big as a human head.

It’s a similar story with the redbud trees, which were just starting to pump out their characteristic, coral-colored blooms on May 4, 1915, but were unmistakably green on May 4, 2017.

This is important for more than aesthetics. Some plants, known as spring ephemerals, have to perform their entire life cycle before the trees above them begin to sprout leaves and choke off the sunlight. For some of these species, climate change could mean a longer growing season, which could be a boon.

For others, it could lead to phenological mismatches, or missed connections, with other species those plants rely upon, such as bees, butterflies, and other pollinators.

“Do they come out earlier and have the same amount of time to do their thing, or are they going to try to do their whole life cycle in a compressed amount of time?” Isaac asks. “We’ll probably have some of each.”

Heberling adds that this change may well benefit invasive plant species like garlic mustard more than natives-so, again, the effects of a warming world are anything but simple. To really understand these changes, the botanists hope to broaden the species they collect each year so to lay the groundwork for a project that will continue for decades or even centuries to come. Eventually, the duo also hope to incorporate a citizen-science component to encourage everyday people to get in on the record keeping.

“This is just the very beginning,” says Heberling.

Beetles offer clues

Polar bears get a lot of headlines for the way scientists project climate change will remake their world. And no wonder. The bears are simultaneously adorable and ferocious, as big as sedans, and easily converted into stuffed animals. But when it comes to actually studying how the world is changing across a variety of habitats, we’d do better to look at the beetles.

There are about 45,000 known species of ground beetle on Earth, with nearly 2,700 species crawling around North America. This family of beetles, officially known as Carabidae, includes fan favorites like the fleet-footed tiger beetles and the explosive bombardier beetles, but also countless species of nondescript black insects that the average person could never hope to recognize. In fact, there may be as many as 600 species of ground beetles hiding out in Pennsylvania-some no bigger than the period found at the end of this sentence.

“People often don’t go into this field because it’s something where you can never know it all,” says Bob Davidson, entomologist and collection manager for invertebrate zoology-aka bugs-at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Entomologist Bob Davidson. Photo: Renee Rosensteel

A six-spotted tiger beetle, a common North American species of ground beetle. Photo: Mike Lewinski

Of course, Davidson knows more than most. Not only does he preside over some 650,000 ground beetles at the museum, but he’s also one of the leading experts for the National Ecological Observatory Network.

Called NEON for short, this network was created in 2012 as a way to take stock of how climate change, land use change, and invasive species are remaking the biosphere. It uses sensor stations and on-site experts to measure an array of variables such as water and air quality, precipitation, and foliage growth from dozens of field sites from Alaska to Puerto Rico. And one of those variables includes sampling for the presence and abundance of ground beetles.

“We know that the entire ecosystem of the earth is all interlocked. And we know from experience that it’s like pick-up sticks. You can keep pulling a piece out and it will stay, but there’s a critical point at which the whole thing collapses.”

– Bob Davidson, entomologist at Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Because there are so many of these critters, Davidson says the Carabidae are useful indicators of ecosystem health. And while the NEON project is only just getting started (the aim is to keep collecting specimens for at least 30 years), there are already worrying reports that ground beetles are in decline. Climate change is surely just one of the factors involved, since the beetles would also be vulnerable to changes in land use, pesticides, invasive species, and a host of other factors. All the same, ground beetles are predators, pollinators, and prey for innumerable other species. And problems at the bottom of the food web have a way of working their way upward and outward.

“We know that the entire ecosystem of the earth is all interlocked,” says Davidson. “And we know from experience that it’s like pick-up sticks. You can keep pulling a piece out and it will stay, but there’s a critical point at which the whole thing collapses.”

Climate science and you

In today’s embattled world, it’s become increasingly difficult to talk about topics like climate change.

“It’s upsetting,” says Nicole Heller, the museum’s newly hired-and the world’s first-curator of the Anthropocene, a cultural term for the broad sum effect humans are having on the planet. “You risk turning people off by showing them information that they don’t really want to deal with because it seems removed from their everyday experience.”

It’s crucial, she notes, that scientists and educators find new and engaging ways to present this information since climate change- as well as other main evidence areas of the Anthropocene, including pollution, habitat alteration, and extinction-touches more than the birds, bugs, and buds in our backyards.

Studies in the social sciences show that facts alone rarely convince anyone to change their point of view. When it comes to engagement with climate change, it helps to examine concrete phenomena that people have experienced.

In western Pennsylvania, that experience might be an intense summer storm. Whether overflow events have sidelined your kayaking plans, or you live in a community that is recovering from flash flood damage, these events are likely more frequent because of climate change. Connections like these provide context for facts and figures, like a study from the National Climate Assessment that found a 78 percent increase in the amount of precipitation falling in extreme weather events in the Northeast between 1958 and 2012-nearly double the increase seen for the Midwest, the region with the next highest increase.

Steve Tonsor, the museum’s director of science and research, says you can boil the whole thing down to fishing, if you like.

While the smallmouth bass he and other fishermen and women prize can grow to around two feet long as adults, these fish begin their lives as tiny larvae. And those larvae are one of the favored foods of dragonfly nymphs.

“The dragonflies are small but voracious predators,” says Tonsor, “with the ability to project their jaws forward nearly instantaneously and grab little fish out of the water.”

Dragonfly larvae hatching is regulated by day length, which means the animals emerge at about the same time every year. On the other hand, bass eggs hatch according to water temperatures, which means their life cycle is more variable. In years where the dragonfly nymphs hatch first, they end up slaughtering the young bass, leaving very few that make it to adulthood. Likewise, when the bass hatch first, they have already beefed up a bit by the time the dragonflies come out and are able to eat the insects instead.

There’s also evidence that smallmouth bass are extending their ranges northwards as the climate warms-all of which is arguably good news for anglers. But even as some species may prosper, others will fade. Tonsor offers up the migrating monarch butterflies, a cherished sight of many a gardener and wildlife enthusiast.

The milkweed plant is not only an important food source for monarch caterpillars, it’s the only plant on which a monarch butterfly will lay its eggs. Photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Monarchs rely on milkweed plants. Even though these plants contain toxins that prevent other animals and insects from eating them, the orange-and-black butterflies have found a way to not only neutralize these bitter compounds, but also repurpose them for their own defense. For roughly 5 million years, the butterflies have relied upon milkweed to provide sustenance and a safe place for their eggs everywhere they roam, from Canada to Mexico. As has been well-publicized, the insects are now having a tougher time completing their epic migration, thanks to our eradication of milkweed. Scientists also suspect climate change will do the monarchs no favors, as they are highly sensitive to extreme weather and rely on temperature as a trigger for reproduction, migration, and hibernation.

In other words, the pick-up sticks are piling up.

Interestingly, Tonsor says that while monarchs have been mooching off milkweed for around 5 million years, scientists figure that the plants evolved their toxic defense some 10 million years before that. Whether it’s monarchs and milkweeds or bass and dragonflies, these intricate relationships between species don’t just happen overnight.

“How long is it before our descendants will see something like that again?” wonders Tonsor. “The scale is millions of years.

“It’s hard for people to wrap their heads around periods of deep time like that, but it’s really worth thinking about.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature