Pittsburghers riding bikes and walking dogs along the North Shore’s river walk over Memorial Day weekend stopped for a minute to watch and listen to a moving service at Carnegie Science Center.

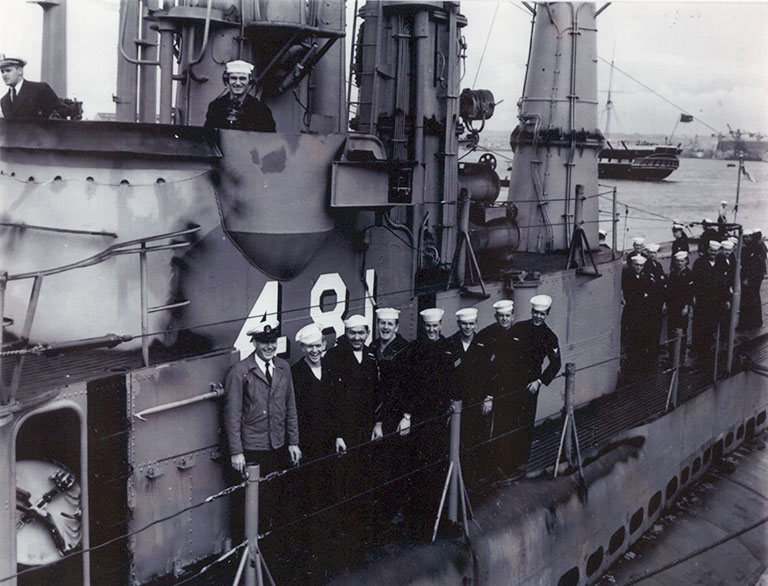

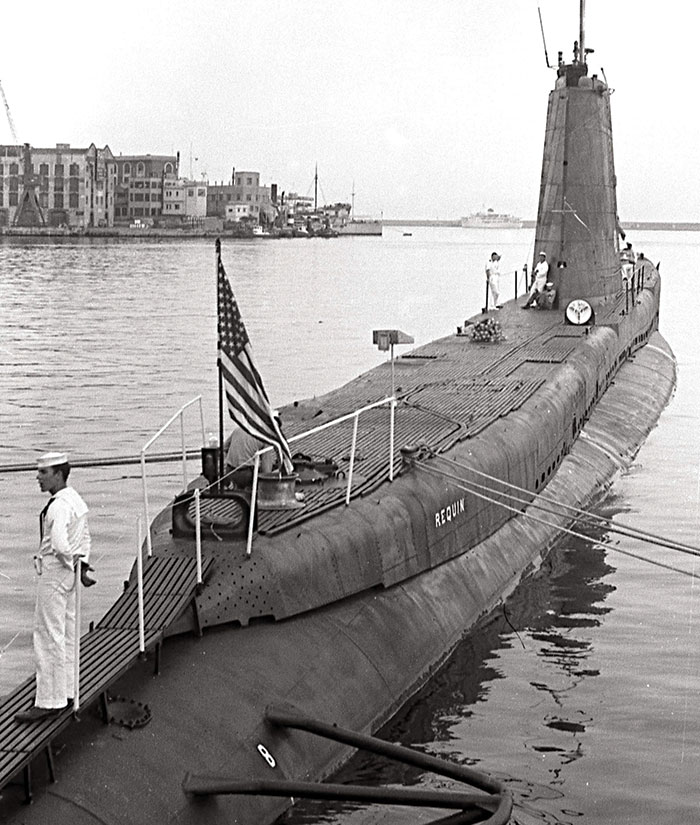

More than 20 Navy veterans perched on the deck of the USS Requin, the submarine that has been moored at the banks of the Ohio River since 1990. Slowly, they read aloud the names of U.S. submarines lost over the years and the numbers of crew members lost with them.

A bell tolled for each vessel and, from the shoreline, a color guard and firing party issued a 21-gun salute. A veteran read from Leslie Nelson Jennings’ poem, Lost Harbor.

There is a port of no return, where ships

May ride at anchor for a little space

And then, some starless night, the cable slips,

Leaving an eddy at the mooring place …

Gulls, veer no longer. Sailor, rest your oar.

No tangled wreckage will be washed ashore.

One of a handful of historic submarines on public view in the United States, Requin lends a poignancy to Memorial Day remembrances of crews who served and sacrificed in the deep. The submarine is especially meaningful to members of the USSVI Requin Base, a group of veterans who meet monthly to honor fallen comrades and celebrate the culture of a unique subset of the military.

“They [subs] were our livelihood,” says USSVI Requin Base Commander Huey Dietrich, of Glenshaw, Pennsylvania, who served on the USS Henry Clay from 1962 to 1965. “We grew up on these and served here and lost our brothers on these. To have one in our hometown is really special to us.”

But now, 78 years after it was commissioned and more than 30 years since it first arrived in Pittsburgh, Requin’s future depends on significant repairs. The Science Center has started to craft a vision for Requin’s next chapter and is seeking funding from foundations, corporations, individual donors, and the government to shore up its future. Specifically, the Science Center will undertake the monumental task of lifting the 1,516-ton craft from the water to repair and restore its deteriorating hull, make cosmetic improvements, and change the way it’s displayed.

“The USS Requin is the single largest item in the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh collection, and it’s our responsibility to make sure it’s preserved,” says Jason Brown, Henry Buhl, Jr., Director of Carnegie Science Center and Vice President of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.

Iconic and Educational

Requin holds the distinction of being the U.S. Navy’s first radar picket submarine—a lookout vessel offering extended radar protection for surface fleets. It would eventually complete stints as a military training sub and tourist attraction before it was nearly sunk to create a coral reef off the coast of Florida in the late 1980s.

The late Pennsylvania Senator John Heinz rescued it by introducing legislation to transfer Requin (pronounced RAY-kwin, French for shark) to the shore of Carnegie Science Center, which opened in 1991. Steel plates covered damaged portions of the hull before barges guided Requin from the Gulf of Mexico, up the Mississippi and Ohio rivers to Pittsburgh.

Once the sub was safely moored in Pittsburgh, the Science Center went about making badly needed repairs to its walls, tiles, and floors. Decades later, Requin now needs considerable exterior maintenance below the water line to keep it ship-shape for its ongoing mission: educating more than 168,000 visitors a year.

“The USS Requin is the single largest item in the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh collection, and it’s our responsibility to make sure it’s preserved.”

–Jason Brown, Director of Carnegie Science Center

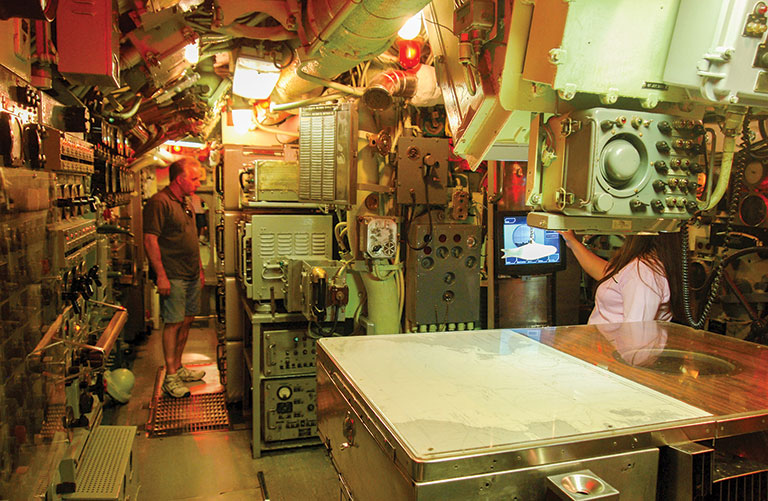

In its own unique way, Requin helps the Science Center fulfill its mission of connecting science and technology with everyday life. Basic sub operations bring scientific concepts alive for visitors: how subs dive and surface, how torpedoes launch, how to navigate with sonar, and how desalination tanks kept the crew stocked with potable water.

And the technology of a diesel-electric sub nearly eight decades old is still surprisingly relevant to modern transportation.

“Requin was powered by modified versions of railroad train engines that ran generators that charged batteries,” says Maria Renzelli, submarine manager for the Science Center. “It essentially works like a hybrid car.”

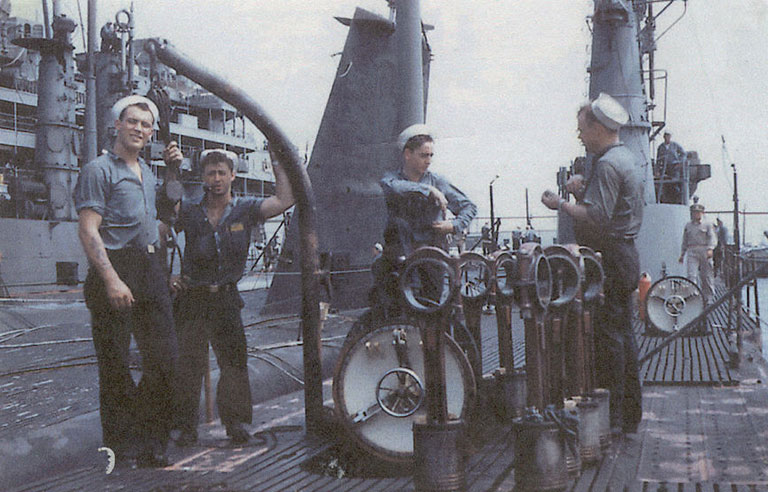

Year after year, busloads of school children cross Requin’s gangway to explore the technology that makes voyaging beneath the sea possible. But the venerable sub’s teaching versatility makes it far more than a floating science lab. Requin provides a window into a different way of living and a snapshot of a bygone era.

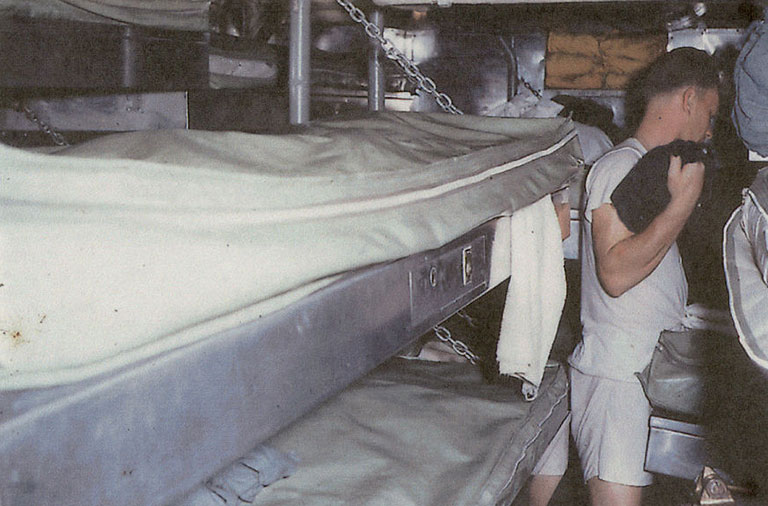

Descending Requin’s narrow stairwells, visitors navigate cramped hallways lined with pipes and equipment and breathe in its distinctive odor—a blend of fuel, hydraulic fluid, metal, and grease.

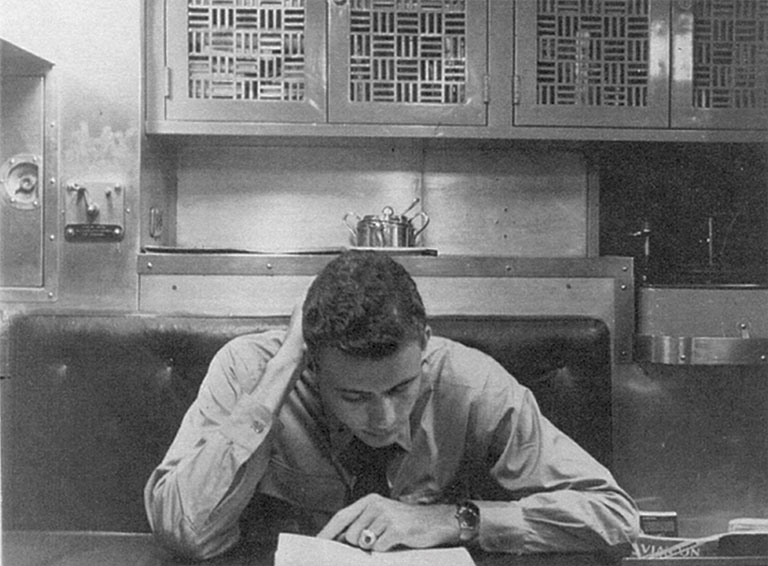

Touring Requin gives people an understanding of what it was like for six to eight dozen men to spend up to 90 days at a time living in extremely close quarters. One visitor said her favorite part of visiting was watching her 6-foot-5-inch boyfriend duck through the sub’s diminutive doorways.

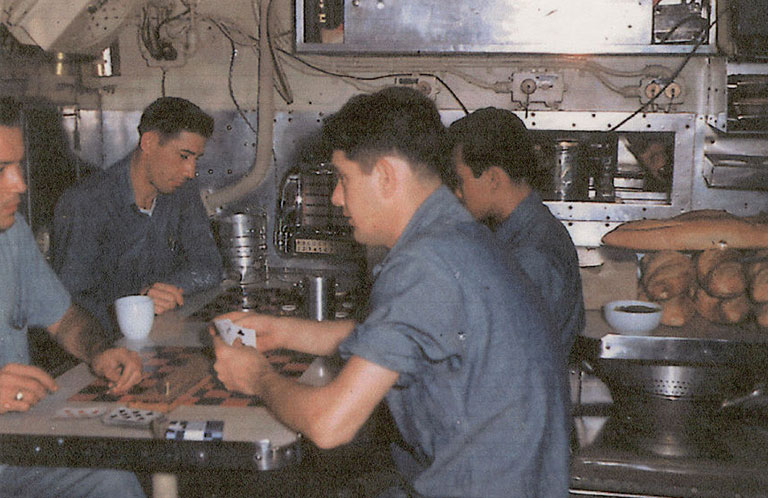

From a group of preschoolers piling into a bunk to test its comfort, to local ham radio operators broadcasting from its radio room, Requin teaches different concepts and means different things to different people.

“Visitors are mostly interested in how they lived,” Renzelli says. “‘Where’s the bathroom?’ is the most common question we get.”

Requin visitors see the officers’ quarters, which afforded a modicum of privacy, and crew quarters, which offered none. A kitchen loaded with food props, a functioning radio room, engine rooms, the control room, and the torpedoes. A favorite spot is the mess deck, where tables painted with checkers, chess, and backgammon boards helped crew members occupy their leisure hours.

More than three decades after Requin’s arrival in Pittsburgh, the Science Center team is still exploring areas of the sub, making new discoveries, and restoring items for public viewing.

Staff recently found the dates of various maintenance procedures scrawled within the maneuvering room. The electronics room—untouched until now—is being inventoried this year. Under the sleeping quarters, Renzelli’s team keeps an archive of items they came across while maintaining and preserving the interior. Their discoveries show how the crew valued and hoarded treats: a desiccated lime; an antique can of cinnamon stashed atop a pipe. Food was squirreled away everywhere.

“Visitors are mostly interested in how they lived. ‘Where’s the bathroom?’ is the most common question we get.”

–Maria Renzelli, submarine manager for Carnegie Science Center

The crew quarters are currently being refurbished to provide more insight into how they were lived in, including ambient sound of snoring and chatter. The crew slept, performed maintenance, and had free time in staggered shifts so men were snoozing, working, and playing around the clock.

North Side resident and USSVI Requin Base member Chuck Loskoch said Requin reminds him of his days “hot bunking” (rotating through shared beds) aboard the USS Tinosa.

Loskoch sports twin hearing aids from working in deep water next to turbo generators running at 36 revolutions per minute.

“There was no such thing as OSHA. We were down there working without earplugs or any kind of protection,” he says. “If you take this away, a good part of the history is gone. This lets people see what it was like in real life.”

Cultivating a Vibrant Future

Brown visited and talked with other institutions that display submarines to see what gives visitors the best experience, including the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry, which displays the USS Blueback in the Willamette River, and the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, which buried its U-505 submarine in an underground bunker.

“You go through this long, concrete tunnel that’s telling you a narrative to get into the underground sub, and at the end of the tunnel, you are face-to-face with a U-boat with its torpedo coming right at you,” Brown says of Chicago’s presentation.

“We want to look at the long term of how our sub continues to be here and how we tell the story of the people who worked on it. We want to create that interpretive component as well.”

The project team will weigh the immediate cost of moving and repairing the sub and the costs of its long-term maintenance as it considers options both for keeping Requin in the water or moving it onto land.

Brown says removing the sub from the water offers two key benefits: slowing the deterioration caused by immersion in the river and allowing the public to view the entirety of the vessel.

This summer, landscape, urban design, and maritime engineering experts, led by LBA Landscape Architecture, began a $350,000 analysis of options for conserving and displaying the sub while enhancing the entire riverfront area alongside the Science Center. Working with Science Center staff and key stakeholders in the community, the group hopes to flesh out a plan and budget for the refurbishment, which will be conducted over the next five to 10 years.

Riverlife, a nonprofit organization devoted to redeveloping Pittsburgh’s downtown riverfront, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are already collaborating on a $20 million project to improve a three-quarter-mile stretch of riverfront from Acrisure Stadium to the West End Bridge.

“Requin itself is an iconic part of the riverfront experience. The destination piece is there, but how we attract new visitors is important.”

–Matthew Galluzzo, president and CEO of Riverlife

“The Science Center sits in the middle of that, so we’re delighted to be able to work with their team on the repositioning of Requin and thinking about its future and how that intersects with our work,” says Matthew Galluzzo, president and CEO of Riverlife.

Developing a naturally graded riparian setback to stabilize the riverbank, restore vegetation, and create 13 new areas of aquatic and floodplain habitats are all on the agenda for Riverlife. A successful project will result in the return of native plant species and an increase in smallmouth bass, which are an indicator of improved environmental conditions for other species of fish, mussels and aquatic life, according to Gavin White, Riverlife’s director of planning and projects.

The collaborators also hope to incorporate more accessible trails to connect the community with the river. Plans are under way to create a community greenspace and develop a pedestrian thoroughfare to link North Shore attractions with the city’s Manchester neighborhood.

“We generally want to see elements that activate and enhance the waterfront, making it more replete with attractions, amenities, and public art,” Galluzzo says. “Requin itself is an iconic part of the riverfront experience. The destination piece is there, but how we attract new visitors is important.”

“Familiarity breeds apathy. We want to remind people about Requin. It’s cool, it’s a benefit to Pittsburgh, it has historical value, and it’s worth saving.”

–Jason Brown

The Science Center has ramped up efforts to increase the sub’s visibility in the community and get people invested in Requin’s future. Among them are special events such as popular “escape room” experiences, the annual commemoration of the anniversary of Requin’s commissioning, and its annual Memorial Day wreath-laying ceremony.

This July brought an Independence Day celebration featuring music performed from the sub and the Science Center’s inaugural Steel Beach Party. Adopting a military tradition of celebrating the halfway point in a voyage with a day on the surface spent

swimming, fishing off the deck, grilling, and enjoying fresh air and sunshine before resubmerging, the Steel Beach Party gave Science Center guests a chance to party like they just spent 45 days below deck.

On select weekends this fall, visitors will be invited to a new escape room experience based on Pittsburgh’s legendary lost B-25 bomber. The escape room proved wildly popular when it launched in 2022, drawing gaming enthusiasts from neighboring states and inquiries from other museums that wanted to create a similarly immersive and fun experience for guests.

“Familiarity breeds apathy,” Brown says. “We want to remind people about Requin. It’s cool, it’s a benefit to Pittsburgh, it has historical value, and it’s worth saving.”

Cementing a Legacy

Capt. Tom Calabrese, of South Fayette, served 30 years as an officer on six subs, then as commanding officer of the Navy ROTC unit at Carnegie Mellon University before “retiring” to work at Bettis naval nuclear laboratory, in West Mifflin, in 2014. He visited Requin with his wife, Deneen, for the 2023 Memorial Day service.

The Calabreses agree Requin provides an important, highly visible reminder of our military’s rich history of ingenuity and service.

“After Pearl Harbor, while the surface fleet fixed itself, subs held the enemy at bay—3,506 men on 52 subs were lost in World War II,” Tom Calabrese says. “We can so easily forget about the sacrifices of those who served before us.”

Requin also sparks curiosity about serving below the surface and military life in general.

“There’s no Navy base here, so this shows people about that branch of the service,” Deneen Calabrese adds.

Renzelli has seen that curiosity bear out. Her team had interacted frequently and developed a special bond with the crew of the USS Pittsburgh before it was decommissioned in 2020. She learned that one of USS Pittsburgh’s crew members was inspired to pursue serving on a submarine after visiting USS Requin as a child.

An honorary member of USSVI Requin Base, Renzelli says sub vets share an uncommon bond. Rank seemed to matter less on a submarine, where everyone needed to have each other’s back.

New recruits were blindfolded and taken to various spots in the sub and quizzed. They had to know every inch of the sub by feel to earn the coveted gold and silver dolphin pins, proving they had completed the rigorous training to become part of the crew family.

Dick Geyer, of West Sunbury in Butler County, enjoyed the camaraderie as well as the discipline of working on a sub. He went on to run a diving team in Holy Loch, Scotland, after six years of service on the USS Toro and USS John Marshall in the early 1960s.

“Every person is qualified to do every duty from bow to aft,” Geyer says. “You have to pay attention to everything that’s going on, and every person depends on everyone else.”

Submarine service was so significant to one former crew member of Requin during World War II that his family requested to place some of his ashes on board. “We are memory keepers for a historic vessel,” Renzelli says. “We’re keeping alive the memory of all who worked on it.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature