As a teacher I am constantly looking for ACT 48 continuing education hours that are actually interesting, so I seek opportunities where I can learn and grow intellectually, both personally and professionally. A few years ago, I happened upon an offering from Carnegie Museum of Art called the Empowered Educators Series. I consider this community of learners one of the museum’s greatest treasures because it has helped make me a better teacher and person by allowing me to connect with some truly inspirational people.

Our inaugural session asked us to “imagine a just world where inequities have been eradicated. How does that society operate? What are your personal experiences living in this world?” First of all, how’s that for an introduction?! Secondly, the idea of a “just world”—is there anything more desirable or needed today? This is a question we need to ask, and a conversation we need to have not only in classrooms but also in our daily lives. And so that was our first meeting, and we haven’t stopped wrestling with sensitive topics, having difficult conversations, or challenging each other to be better in every way. Regardless of how frustrated, stressed, or tired we were after working all day, these were sessions we all embraced.

Over the years we have talked about race and social justice, Pittsburgh’s history of inequality in gender and race, how to build new worlds and Black futures, and invisibility and erasure. This last example was particularly powerful in that we were asked how we could annotate the spaces of our schools to tell the invisible stories. Who would we include? Who would we leave out? We were asked how we might amend our curriculums, keeping the same premise in mind. My students at McKeesport High School, where I’m entering my 23rd year as an English teacher and which has one of the most racially diverse student populations in Allegheny County, were quick to point out the lack of Black teachers in our school (I am white), and that the English curriculum rarely goes beyond Martin Luther King, Jr. in its representations of writers of color.

All of the topics discussed are vitally important to our lives in and out of school. As teachers, we’ve been able to take these conversations back to our classrooms to help our students express themselves about these issues that have real-life consequences, such as the school-to-prison pipeline for far too many Black students, or the inequity in disciplining Black and white students. The learning has also helped us think more critically about our roles, and how we can effect change in our schools and communities.

“As teachers, we’ve been able to take these conversations back to our classrooms to help our students express themselves about these issues that have real-life consequences.”

We were asked to write our responses to the following prompts: “My perception of power is …” and “I use my power to …” As a teacher, these are profoundly impactful ideas. I shared with my colleagues my belief that power is not control, but the ability to be oneself. It is the ability to be who you are, warts and wonders and all. It’s the ability to let the world see that you are someone who matters. And how I use my power is to offer a safe space for anyone and everyone to be themselves, without contingencies or restraints. In a school, teachers are role models, and that’s a powerful position to be in, so having honest conversations with students is something they welcome and hunger for. Being a part of Empowered Educators has helped me have these conversations by giving me tools to use and impressing upon us all that we do important work by allowing students to recognize that they have power, too.

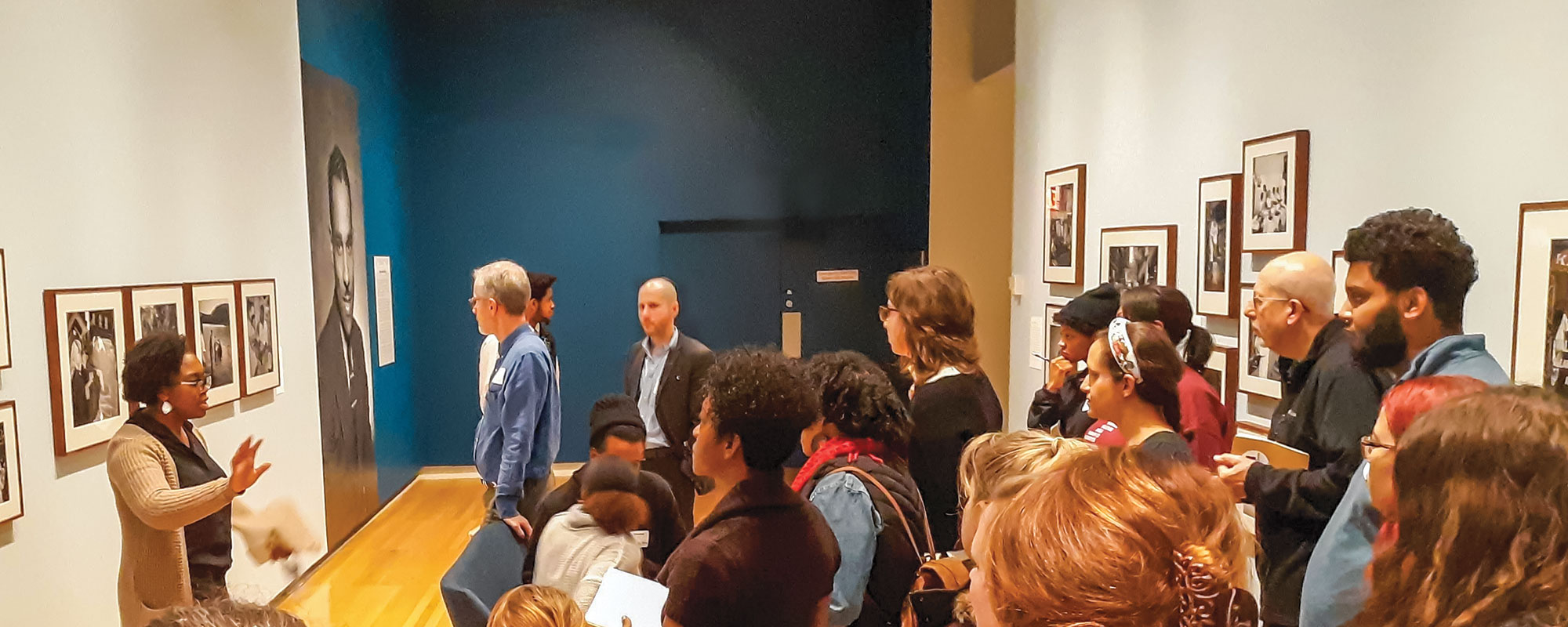

We explored the magnificent photography of Pittsburgh’s very own Charles “Teenie” Harris, whose archive is stewarded by the museum and used in area classrooms. Students write stories based on what they see in his images that document the city’s historic Black community from 1935 to 1975. A few things my students noticed and wrote about were that Harris photographed not just Black people but had many pictures of white people also. They were surprised by the many Black men in military uniforms. And the students noted how often Harris chronicled scenes of death, whether it was the pictures of children in caskets or a body covered with a blanket on a Hill District porch. Death is something too familiar in McKeesport, particularly of the young.

We teachers walked the museum’s galleries in order to note what we saw, and invisibility and erasure again arose as we viewed predominantly white characters and subjects in the artworks. This led to discussions about the Guerrilla Girls, activist-artists dedicated to exposing gender and racial bias in the art world, and how Carnegie Museum of Art is actively working to make its holdings more diverse. We experienced extraordinary guest speakers who offered insights and inspiration.

The Empowered Educators Series has been an eye-opening and motivating experience for me. What began as a search for Act 48 credits has turned into the discovery of a community of teachers giving voice to our students and hope for a more just world.

Carnegie Museum of Art partners with the Center for Urban Education, Western Pennsylvania Writing Project, and PittEd Justice Collective for the Empowered Educators Series, with support from The Grable Foundation. Register for upcoming sessions, which are free, on Nov. 18, Dec. 16, Feb. 17, March 17, and May 19 by contacting teachers@cmoa.org.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up