T. rex Holotype

Despite their relatively puny arms, Tyrannosaurus rex had the jaw-dropping power of a 40-foot-long, 5-ton body. And their spiky teeth were sharp, efficient, and deadly. Roaming what is today the western U.S. and southwestern Canada in search of food, the meat-eating T. rex ruled some 68 to 66 million years ago during the late Cretaceous Period. But it wasn’t until 1902 that the holotype—the scientific name-bearing specimen and the one to which all others must be compared—was unearthed at Hell Creek, Montana. At the turn of the century, the competition among museums to discover and display dinosaur fossils was fierce. Young fossil hunter Barnum Brown was hired by New York’s American Museum of Natural History to lead its charge, and he did not disappoint. Over three years, he unearthed what was at the time a whole new species of dinosaur. But it didn’t take long before Brown moved on to bigger and better findings. His 1908 excavation of a more complete T. rex skeleton prompted the museum to move the holotype into storage, and in 1941, with a dwindling research budget, the American Museum sold the T. rex holotype to Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The price? $7,000 ($130,000 in today’s currency) for what is by definition the first fossil of the world’s most famous dinosaur.

Richard Serra, Carnegie, 1985, Given in memory of William R. Roesch by his wife Jane Holt Roesch © Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York | Photo: Tom Little

Richard Serra’s Carnegie

As the 1985 Carnegie International approached, sculptor Richard Serra was mired in controversy surrounding his public sculpture Tilted Arc. Some New Yorkers weren’t happy about having to negotiate its curving wall of raw steel outside the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in Lower Manhattan. It prompted a local court battle to have the artwork removed and a national debate about the purpose and placement of public art. But when a massive crane arrived on Forbes Avenue in front of Carnegie Museum of Art to position the four Cor-Ten steel panels that would lean against each other to form Serra’s 40-foot tower titled Carnegie, no one voiced any concerns or objections. The reaction was quite the opposite. People were intrigued by the sculpture’s interesting edges and angles, not to mention its weathering patina. Serra’s Carnegie emerged as one of two winners of the prestigious Carnegie Prize and it still stands near the museum’s front door. Its title conveys the industrial legacy of art in Pittsburgh by recalling both the museum and its founder, Andrew Carnegie, whose U.S. Steel Corp. invented Cor-Ten steel.

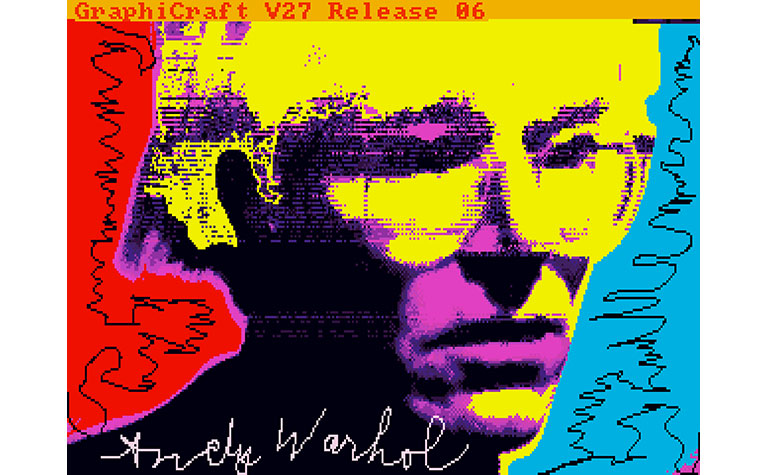

Andy Warhol, Andy1, 1985, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Andy Warhol’s Amiga Digital Art

In 1985, the electronics company Commodore introduced the world to the then-revolutionary Amiga 1000 personal computer. Amid great fanfare that featured a full orchestra and tuxedo-clad employees, the PC took center stage at New York City’s Lincoln Center, accompanied by two revolutionaries in their own right—Andy Warhol and Blondie’s Debbie Harry. Never one to miss an opportunity to explore uncharted media, Warhol eagerly took on his new role as a Commodore brand ambassador. His assignment that day: Use the Amiga’s ProPaint software to create a portrait of Harry in real time in front of a live audience. Warhol accomplished that goal, and more. For decades, 28 of his digital works—among them, two self-portraits and the untitled renderings of a banana and Campbell’s soup can—existed only on floppy disks stored within The Warhol’s archives. Then in 2014, the museum, artist Cory Arcangel, Carnegie Museum of Art, and Carnegie Mellon University’s computer club set out to rescue the paintings from their decadeslong purgatory. After painstakingly reverse-engineering the program, the CMU squad revived Warhol’s digital images. In May 2021, five of them were minted and auctioned as nonfungible tokens by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. and Christie’s.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, No Need of Speech, 2018, Purchase, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Scaife, by exchange © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Corvi-Mora, London.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s No Need of Speech

At first glance, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s timeless paintings seem to recall the classic style of portraitists who have come before her. And so, one might assume that her subjects, a predominantly Black cast of characters, sit for days as she studies their faces, gestures—their very souls. But the people who populate her world don’t exist in ours. They are manifestations of the British-Ghanaian artist’s imagination, composites of images found in scrapbooks and magazines, and hinted at in her own writings. The creation of each large oil-on-linen canvas usually begins and ends in one exhaustive eight-hour session. Yet despite that sense of immediacy, the paintings purposefully betray no sense of time or place. In 2018, she created 13 new works for that year’s Carnegie International—including No Need of Speech, now part of the museum’s collection—earning her the prestigious Carnegie Prize.

Andy Warhol, Endangered Species: San Francisco Silverspot, 1983, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Andy Warhol’s Endangered Species series

Luminaries such as Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor weren’t the only treasures to receive Andy Warhol’s silkscreened star treatment. The artist’s 1983 Endangered Species series features 10 creatures great (the African Elephant and Black Rhinoceros) and small (the San Francisco Silverspot and Pine Barrens Tree Frog) who, thanks to human behavior, had found themselves in a perilous position. Placed on the endangered species list, they were facing the very real possibility of extinction. The project started with a conversation between Warhol and the environmentally conscious art dealers Ronald and Frayda Feldman. The idea was to use the Pop icon’s celebrity status to call attention to the plight of animals around the world. Warhol deployed his signature style—choosing bold, vibrant colors for each portrait, prompting him to refer to the collection as “animals in makeup.” Unfortunately, eight of the 10 animals remain endangered.

Bontebok

In 1837, a farming family in South Africa’s Western Cape Province realized that the bontebok, an antelope native to the region and distinguished by its white markings and ringed antlers, was in danger of extinction. Knowing the animals couldn’t jump very high, they enclosed the few remaining bonteboks they could find using a simple 4-foot-tall fence. Thanks to this intervention and subsequent conservation efforts, the animal’s numbers have increased from just 17 to 158 in a national park in South Africa, and about 6,000 worldwide. The species is not out of the woods yet, though. In 2011, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service confiscated a bontebok from a shipment at Los Angeles International Airport that included 20 mounted mammals from South Africa. As is the agency’s policy, the mount of the endangered animal was not returned to its country of origin. It was offered to Carnegie Museum of Natural History as a teaching tool, making it one of the few on view in North America. It’s part of the museum’s Hall of African Wildlife and is the only animal on display to have been acquired while endangered. Many older dioramas include animals that, though endangered now, were hunted and collected legally, in some cases more than 100 years ago.

Heartbeat Drum

First there’s the lub, then there’s the dub: the sounds of the heart at work. Although the heart—its four chambers, valves, and vessels—is essentially the same in all mammals, its drumbeat pace is much more variable. Basically, the larger the creature, the slower the heart rate. Elephants: 30 beats per minute. Pygmy shrews: 1,300. Humans rest somewhere in the middle at 60 to 100. At Carnegie Science Center, you can hear the difference for yourself. As part of its interactive BodyWorks exhibition, which highlights the marvelous machine that is the human body, you can place your hands on a set of metal handprints and discover the answer to the question, “How fast is my heartbeat?”

Big Joe

It’s estimated that the art handlers at Carnegie Museum of Art move between 1,000 and 2,000 works of art each year, depending on the year’s activity. “Oddly, we’ll often handle the same object five or six times, and occasionally more, as we work through an accession, exhibition, or collections project,” says Mark Blatnik, the museum’s chief preparator. When an artwork is unusually large or heavy or in a tricky location, to protect both the art and the handlers, the team brings in “Big Joe,” a Class III electric walkie stacker, for an assist. Pictured here, the team installs Ary Scheffer’s 1851 masterwork depicting the swirling shades of entwined lovers Francesca and Paolo from Dante’s Inferno. They’re using a frame fashioned from an oversized painting cart (dubbed the S.S. Steve for its creator) to provide support and security for the painting, while Big Joe provides the muscle to make the lift. Purchased with funds from Carnegie Museum of Art’s Women’s Committee, the equipment is key to the art of moving artwork safely.

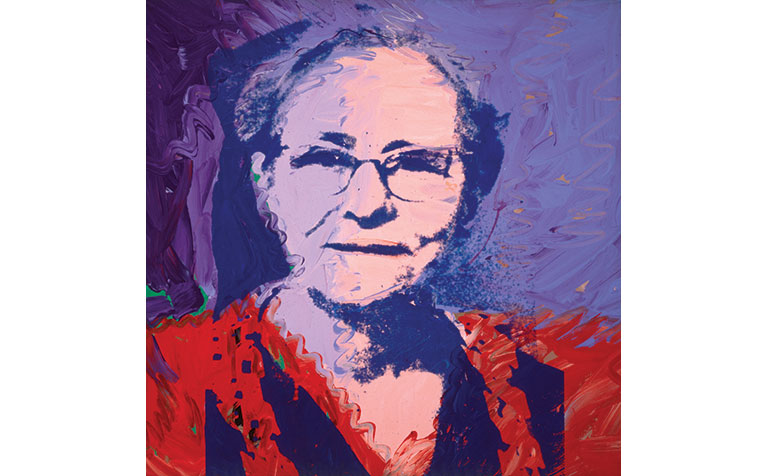

Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, 1974, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Portrait of Julia Warhola

There is an intimacy in Andy Warhol’s portraits of his mother, Julia Warhola, that distinguishes them from his other works. Julia was a constant in Andy’s life, overseeing his religious upbringing in the Byzantine Catholic faith and taking care of his many medical needs as a child. An artist herself, Julia quickly recognized and nurtured her youngest son’s talent, making sure he went to college to study art. Following his graduation, she soon joined him in New York City where the two not only became roommates—an arrangement that lasted nearly two decades—but also artistic collaborators. Julia’s decorative handwriting was a factor in Warhol’s early commercial success. Still, there’s more to the portraits than history. Completed just two years after her death in 1972, the paintings show the artist’s mother in full “Bubba” mode, complete with apron and granny glasses. The color palette is muted, in sharp contrast to Warhol’s famous electric celebrity portraits. And, perhaps most striking of all, Warhol made embellishments using his fingers, which are visible around his mother’s head and shoulders, a rare hands-on approach for the artist.

The Water Table

One of Carnegie Science Center’s most popular spots for its youngest explorers involves dropping a line in a fishing pond and keeping boats afloat in a clawfoot bathtub. Part of the Little Learner’s Clubhouse on the fourth floor, the water table is a great place for making real-world connections to water sources we use every day—and a splash. No water table at home? No problem. A bathtub and a few plastic containers can also make a great science lab.

John Snow, an African Pied Crow

The pied crow is an adaptable bird that can be spotted from Sub-Saharan Africa down to the Cape of Good Hope, Madagascar, and Zanzibar. Black with a distinctive white patch that wraps around its body like a vest, it can also be found at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Nicknamed John Snow after the Game of Thrones character, the museum’s pied crow is one of the stars of its Living Collection, a group of animal ambassadors that teach visitors about their wild counterparts. Like other crows and ravens, the pied crow is highly intelligent, and John’s animal handlers say he’s easily the brainiest in the collection. Recent studies show that birds belonging to the genus Corvus, including the pied crow, have the same cognitive function as children ages 5 to 7. They’re able to mimic sounds and speech like some parrots, and John knows several phrases, including “good boy,” “baby bird,” and “I love you.”

Sports Challenge at Highmark SportsWorks

Run, bounce, spin, fly—and learn—is the mantra at Highmark SportsWorks®. In sports-obsessed Pittsburgh, it’s fitting that Carnegie Science Center filled an entire building with experiences that are also a gateway to the physics, anatomy, biology, and even chemistry behind popular sports. Adjacent to the main museum, the attraction includes a section called Sports Challenge, in which visitors can test themselves against the skills of elite athletes, all the while learning techniques for improving performance through better nutrition and safe warmup exercises. Those who want to test their speed can run the 10-meter dash down the track, chasing a hologram of Lauryn Williams, local track star and Olympic silver medalist. Competitors can check their reflexes against an NHL goalie with a whack-a-mole-style game. And one of the newest Olympic sports to debut in Tokyo, skateboarding, is featured in an exhibit that challenges visitors to adjust their center of gravity to keep them from falling off the board as they “hang 10.”

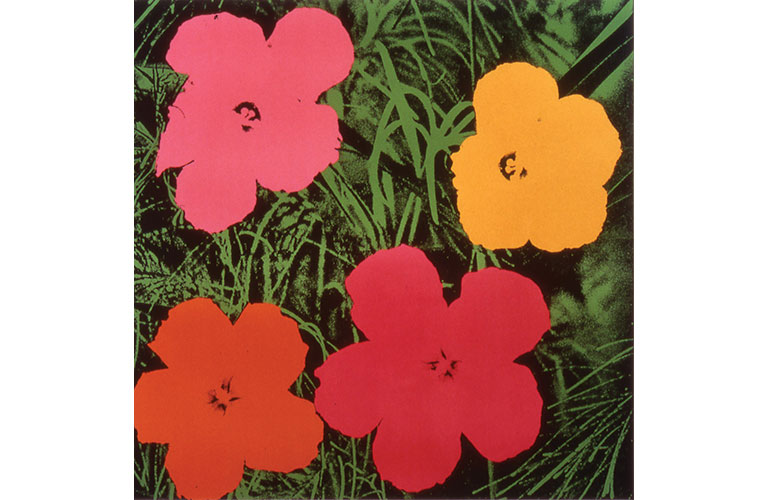

Andy Warhol, Flowers, 1964, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Andy Warhol’s Flowers

“The reason I’m painting this way,” Andy Warhol famously told ARTnews in 1962, “is that I want to be a machine.” The machine-like method he was referring to is photographic silkscreen printing, a process that allowed him to quickly reproduce images en masse. For his iconic Flowers series, Warhol set his sights on a photograph of four hibiscus flowers in Modern Photography magazine taken by Patricia Caulfield. Changing its contrast and cropping the image into a square format, Warhol sent it to a commercial silkscreen maker with exacting specifications. Then, with the help of assistants, he copied it across more than 500 canvases, methodically producing paintings in different sizes—mirroring the options of small, medium, large, and extra-large in consumer culture—but with each new reproduction he would apply his own signature style. Caulfield was not amused. She sued Warhol but ultimately settled out of court for a reported $6,000, two paintings, and future royalties. When the canvases were exhibited in Paris and New York in 1964 and 1965, Warhol exploited the serial arrangement and variation in the series by responding to the architecture of each gallery and installing the works in floor-to-ceiling grids, resulting in an immersive environment.

Storyteller

Potter Helen Cordero, who was born in 1915 in Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, is known for her popular storyteller figures from Cochiti folklore. She formed the figures from clay found around her home and fired them over an open cedar flame. Inspired by memories of her paternal grandfather, a Cochiti storyteller who Cordero says was always surrounded by small children, she created many likenesses similar to the storyteller on view in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians. She said of her grandfather, “He would put us on his lap or wherever we could sit. His eyes are closed because he was thinking; his mouth is open because he is chanting or telling stories.” In 1964, when she sold her then-experimental storyteller figures based on her “singing mother” motif, Cordero’s work helped revive interest in Pueblo pottery. Her figures have been exhibited in museums across the U.S. and Canada.

Image courtesy Jeff Brown

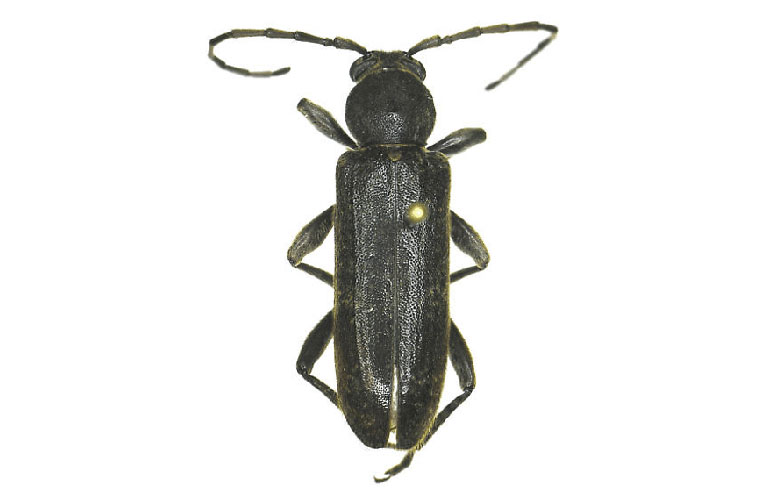

Velvet long-horned beetle

Behind the scenes in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s world-famous bug rooms, a small group of researchers screen and identify some 60,000 insects each year as part of the museum’s Biodiversity Services Facility (BSF). Their charge: Detect unwanted invasive species—think moths and bark- and wood-boring beetles—that can cause billions of dollars in damage to crops and forests. What the museum has to offer is quite unique: a massive comparative collection and the expertise to translate it. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and numerous state departments of agriculture set insect traps, collect the raw samples, and then ship their catches to the museum’s expert entomologists, who check the insects against the USDA’s National Priority Pest List and an ever-increasing target list of worrisome species. The velvet long-horned beetle is just one example of a species introduced to the United States and detected in BSF samples. Native to the Old World, it’s monitored and managed by states, as it infests fruit, forest, and ornamental trees, damaging both timber and lumber.

Teeny tiny trees

People visit Carnegie Science Center’s Miniature Railroad & Village® to see the sights: the historically accurate and meticulously crafted replicas of some of the region’s most significant and beloved landmarks—Fallingwater, Forbes Field, and Kaufmann’s Department Store among them. But what about the famous display’s trees—all 250,000 of them? They infuse each scene with a sense of vitality and reality. Some trees are in full summer mode, while others are showing off the changing hues of fall; each one handmade, a feat that can take hours to complete. The process starts with the twisting and bending of a copper wire to form the trunk and limbs. Flower tops from dried hydrangea plants harvested every autumn by Science Center staffers are then affixed with hot glue. Finally, the trunk and branches are coated with a layer of hot beeswax to mimic bark. The result: a one-of-a-kind tiny tree.

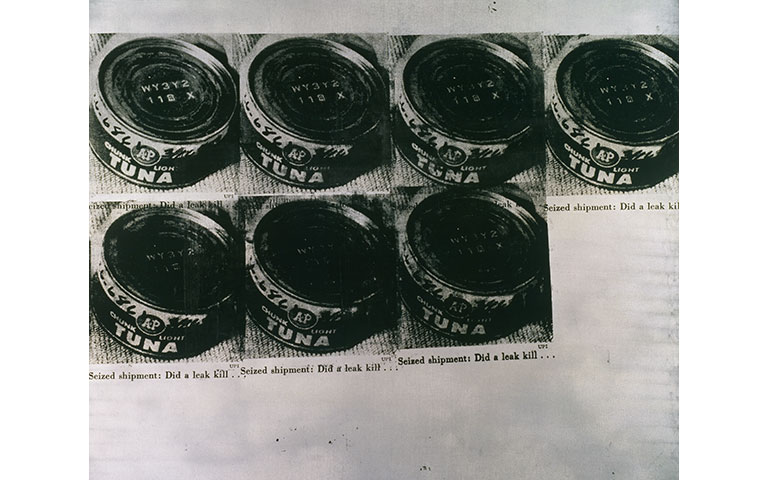

Andy Warhol, Tunafish Disaster, 1963, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Warhol’s Tunafish Disaster

The April 1, 1963, edition of Newsweek contained an article about a contaminated can of tuna that killed two housewives in suburban Detroit. Andy Warhol, news junkie that he was, ripped the photo from the headlines and appropriated it for his art. In his painting of the same year titled Tunafish Disaster, he repeated the image of the tuna can with its cutoff caption seven times on a silver background. Well before the advent of social media, the Pop art innovator instinctively understood the power of mass media. He plucked images from other horrific scenes—car crashes, nuclear explosions, suicides—for his Death and Disaster series, and he used a gruesome kind of repetition in works such as his Electric Chair series to convey the way society has become numb to it. In an interview with ARTnews, Warhol explained that he began the series when he read the front page of a newspaper chronicling a plane crash. It read: 129 Die. “I realized that everything I was doing must have been Death. … Every time you turned on the radio they said something like ‘4 million are going to die.’ That started it. But when you see a gruesome picture over and over again, it really doesn’t have any effect.”

Gorilla (formerly known as George)

He was born in Gabon, West Africa, but after being captured at a young age in the 1960s he spent most of his 14 years in zoos, initially in Copenhagen, Denmark, and then for a decade at the Pittsburgh Zoo. Growing to a remarkable 350 pounds, the silverback western lowland gorilla was known simply as George to a generation of Pittsburghers, many of whom still remember his playful antics at the zoo. Although the animal died unexpectedly in 1979 from complications of an infected tooth, thanks to skilled taxidermists he found new life in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Hall of African Wildlife. His silence speaks to new generations. It serves as a warning that all gorillas are in danger of extinction as humans continue to illegally hunt them and invade their natural habitats.

Dan Graham, Heart Pavilion, 1991, A. W. Mellon Acquisition Endowment Fund and Carnegie International Acquisition Fund © Dan Graham. By permission.

Heart Pavilion

The heart-shaped aluminum and glass structure created by Dan Graham for the 1991 Carnegie International is a visitor favorite in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Scaife Galleries. At first glance, the nearly 8-foot-tall and 14-foot-wide installation projects the architectural gravitas and cool detachment of an urban skyscraper. But as viewers inch closer, its surface—both transparent and reflective—provides a much more intimate experience. As visitors wander in and around the Heart Pavilion, they see their own reflections and watch as total strangers enter the space, becoming an integral part of the installation. “My pavilions derive their meaning from the people who look at themselves and others, and who are being looked at themselves,” said Graham, a seminal figure in contemporary art. “Without people in them, they might look a bit like minimal-art sculptures, but that’s not what they’re meant to be.”

Tools for tracking birds

Powdermill Avian Research Center has always sought to provide a bird’s eye view of the world. Established 60 years ago as part of Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s environmental research center, it reached a remarkable milestone this summer in banding its 800,000th bird. Each tiny aluminum bracelet bearing a nine-digit identification number and slipped onto a bird’s leg gives avian researchers a crucial snapshot of bird populations and their migration patterns. And while banding is invaluable for long-term studies, it only tells us something when a bird is caught by another researcher or found dead by someone who knows to submit the data online. We don’t know where they go on their journey, and why. By using the emerging technology known as Motus Wildlife Tracking, Powdermill researchers are now also receiving real-time data by attaching tiny, lightweight transmitters to birds. Paired with a large-scale network of receiving stations, radios can pick up the signal from a transmitter up to 9 miles away. Because each transmitter produces a unique ping, a bird wearing one is under surveillance everywhere it goes, sometimes for life.

John Kane, Bloomfield Bridge, c. 1930, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James H. Beal

John Kane’s Bloomfield Bridge

John Kane, who emigrated from Scotland in the late 1870s at age 19, helped build industrial Pittsburgh by performing backbreaking labor. In the aftermath of a freak accident in which he severed his leg at age 31, he increasingly turned to his childhood love of drawing. With no professional training, it seemed unlikely that his art would ever be recognized. But when he was 67, one of his paintings was accepted into Carnegie Museum of Art’s International Exhibition of Paintings, now known as the Carnegie International. Breaking into the prestigious exhibition in 1927—his second attempt after being rejected the previous year—wasn’t a fluke. Kane’s artwork appeared in the show six more times and was quickly added to the collections of not only Carnegie Museum of Art (which houses 17 of his paintings and four drawings) but also New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Many of Kane’s paintings depict classic Pittsburgh scenes—like his portrayal of the Bloomfield Bridge—in a hopeful light. Asked why Pittsburgh was his muse, Kane replied: “I helped to build its steel mills and homes; I paved its streets, made its steel, and painted its houses. It is my city; why shouldn’t I paint it?”

50-million-year-old Fossil Fish

Three years before Diplodocus carnegii (aka Dippy) captured Andrew Carnegie’s imagination, a roughly 50-million-year-old fish fossil became the first specimen to enter Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s vertebrate paleontology collection, now world famous for its Jurassic dinosaurs. Donated by Frank F. Nicola in 1896, the fossil was discovered in the Green River Formation in Wyoming, one of the most important sites for understanding the Eocene Epoch. While the collection that spans a staggering 465 million years is heralded for its dinosaurs, they account for only a small fraction of its holdings, with a surprising 79% being mammals, 12% fish, 5% reptiles—including an impressive 760 dinosaur fossils—3% amphibians, and 1% birds. Fossil fish are a strength of the collection due largely to the early purchase of the Baron de Bayet Collection, one of the finest groupings of European fossils in North America, complete with ancient plants, squid and cuttlefish relatives, and flying insects. William Jacob Holland, the museum’s second director, told Carnegie that the 1903 acquisition “will make our museum one of the Gibraltars of paleontological science in the world,” and many of the specimens are on view today in Dinosaurs in Their Time.

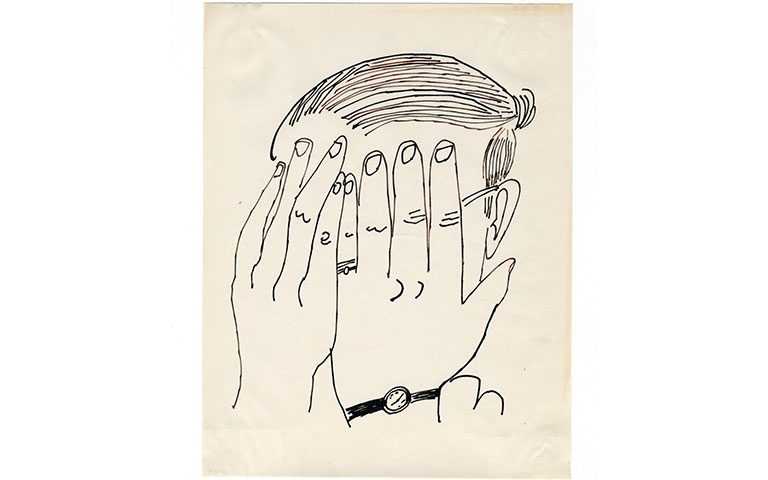

Andy Warhol, Self-Portrait, ca. 1953, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Andy Warhol Self-Portrait

Andy Warhol traced this 1953 self-portrait from a photograph taken by Otto Fenn, but it’s not a unique image. He repeated this pose with other photographers including McKeesport native Duane Michals and Edward Wallowitch, one of his earliest boyfriends. “This portrait reminds me of the struggles and rejection that Warhol faced during his entrée into New York’s elite art scene,” says Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art. “But it also speaks to his youthful, unyielding aspiration for fame and attention—his drive, which he’s safely guarding behind those tender hands.”

River Aquarium

While taking in the spectacular view of the confluence of Pittsburgh’s three rivers, the hope is that visitors to Carnegie Science Center’s first-floor H2Oh! gallery will gain a newfound appreciation for these complex and fragile ecosystems that provide drinking water and support recreation, commerce, and native wildlife. The exhibition’s river aquarium, which weighs in at nearly

3 tons, mimics the rivers outside by maintaining a temperature of 72 degrees Fahrenheit and showcasing native game fish: the critically imperiled longear sunfish, green and redear sunfish, yellow perch, and, soon, rock bass and the endangered warmouth—all surprisingly beautiful critters to those who might think of freshwater fish as drab. “Many anglers come in shocked by the large size of our fish compared to the same species caught in the wild,” says Carla Littleton, animals and habitats manager. “It gives the perfect platform to talk about overfishing and the importance of proper catch-and-release techniques to preserve wild

fish stocks.”

Art Cat

Art Cat, the mascot for Carnegie Museum of Art’s youth programs, lives in the museum. The gray feline with a red beret and jaunty scarf knows all the museum’s secrets. He’s also a budding artist, taking a sketchbook wherever he goes. Like any good mascot, he gets the crowd pumped, inspiring young artists to help him finish his doodles. Technically, he’s a stuffed animal, but don’t tell him that. He has an excellent pedigree, created by artist Dave Klug. He’s bursting with ideas that he can’t complete himself—what with all the naps he takes throughout the day. Art Cat’s Sketchbook, sold at the museum store, invites kids to draw a background scene for a suit of medieval armor. Another Art Cat idea—for kids and their adults—imagines what the people in museum portraits might say to you if they could talk.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Where Art & Science Meet