There are problems, and then there are wicked problems. These existential dilemmas, such as climate change and the legacy of colonialism, have been in the making for generations and promise no simple solutions.

“Wicked problems require integration and synthesis,” says Stephen Tonsor, the Daniel G. and Carole L. Kamin Interim Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. That’s why the museum is taking a decidedly integrated approach to its scientific research and outreach, enlisting a corps of new scientists eager to collaborate with the museum’s renowned scientific team, and each other, on ongoing and novel research, exhibitions, and community-based science.

Among those joining the ranks within the past eight months: Bonnie McGill, an ecosystem ecologist and science communicator; Travis Olds, a mineralogist, crystallographer, and materials scientist; and Carla Rosenfeld, an environmental biogeochemist.

From their perspective, this cross-disciplinary approach will allow them to expand their science beyond the inherent restraints of academia.

Bonnie McGill samples spring cover crops from an Iowa cornfield. Cover crops provide multiple benefits, including retaining nitrogen in the soil, which prevents river pollution, the topic of her Smith Fellowship research.

“I could have applied for a university job and made a career out of building watershed models showing what’s going on with nitrate in rivers,” says McGill, who in 2018 completed the David H. Smith Conservation Research Fellowship in Iowa, the nation’s premier postdoctoral program in conservation science. “But there are people already doing that. This job at the museum was an opportunity to translate the science and empower communities to weigh the scientific evidence in their decision making.”

That’s exactly what Tonsor had in mind back in 2015 when, as director of science and research, he first started to imagine a different kind of future for the now 124-year-old institution. “It’s been a deliberate process,” he says. “We’ve been contemplating not only what it means to be a natural history museum in the 21st century, but also what it means to be human, to be inextricably linked to nature.”

And to each other.

Breaking Down Barriers

Traditionally, natural history museums are staffed with taxonomists whose primary functions are to identify and catalog specimens, from minerals to mammals and birds to insects. Building relationships with fellow scientists and the public is not typically a top priority. Carnegie Museum of Natural History was no exception to this rule. But by instituting an interdisciplinary approach to confronting urgent challenges such as environmental degradation and biodiversity loss, the museum is forging a new model. In 2018, the museum hired Nicole Heller as the world’s first curator of the Anthropocene, and the institution’s focus strategically shifted to the interconnectedness of the sciences, and of humans and nature.

Tonsor is committed to establishing a think tank, an environment within the museum that encourages—and expects—researchers to reach beyond the boundaries of their fields and take action by sharing ideas, interpreting data, and interacting with a variety of different communities.

McGill is doing just that in her role as science communication fellow within Anthropocene studies.

“We want to encourage communities to take real action in ways that connect to their specific locations and cultural values.” – Bonnie McGill, ecosystem ecologist

Unlike geological epochs before it, the Anthropocene is all about us—humans—and how our behavior, including our seemingly insatiable use of fossil fuels, has been the major cause of climate change and other irreversible changes to the planet.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History has opened the door to the Anthropocene, as visitors can literally pull up a chair in the Anthropocene Living Room and, in a casual, comfortable space, learn more about it.

McGill shares with farmers and other Mercer County residents prints of museum herbarium specimens from western Pennsylvania to show changes in plant life cycles from 100 years ago to today in response to climate change.

“We’re interested in changing the narrative from doom and gloom to success stories of resilience and figuring out how to talk about climate change without getting mired in politics,” McGill says. “We want to encourage communities to take real action in ways that connect to their specific locations and cultural values.”

McGill and her museum education colleagues are working to bridge the gap between science and those communities. As part of a $1.2 million grant from the National Science Foundation, they’re actively listening to and working alongside Mercer County farmers, among others, to better communicate the effects of climate change in rural communities.

It’s a step toward actionable science. “Part of my job is to take a community’s questions and concerns to the right people and then return with locally relevant, meaningful, and productive information,” says McGill.

For example, many of the museum’s collaborators talk about the increasing rainfall and are curious if that shows up in the data. “People know what’s happening in their backyard. Validating that experience with scientific analysis helps build science literacy,” says McGill. So she downloaded more than 100 years of weather station data from Mercer and surrounding counties, and walked community members through her analyses, including evidence that the number of days with over one inch of precipitation has increased significantly, especially in the fall.

Behind the scenes at the museum, Travis Olds and Carla Rosenfeld, the new assistant curators in minerals and earth sciences, respectively, are joining forces to understand similar questions related to human activity.

One of their overarching goals is to build a research lab that would not only rival those found in universities, but also offer the benefits that only a natural history museum could provide.

Travis Olds and Carla Rosenfeld, behind the scenes in the section of minerals and earth sciences, are a new kind of pairing at natural history museums. Photo: Joshua Franzos

“I think it will be a unique facility,” Olds says. “There aren’t many other advanced analytical labs that have access to an enormous in-house mineral collection—some 30,000 specimens. And as far as I know, there aren’t many—if any—museums that will have a mineralogist like me working directly with an environmental scientist like Carla.”

Earth system scientists are indeed a rare species at most natural history museums. As Carnegie Museum firsts, Rosenfeld and McGill study human-caused change on whole earth systems such as watersheds, ecosystems, and the atmosphere. And instead of collecting rocks and biological specimens like their natural history colleagues, out in the field they collect samples of water, microorganisms, and soil.

“There aren’t many other advanced analytical labs that have access to an enormous in-house mineral collection—some 30,000 specimens. And as far as I know, there aren’t many—if any—museums that will have a mineralogist like me working directly with an environmental scientist like Carla [Rosenfeld].” – Travis Olds, assistant curator of minerals

As Tonsor sees things, it’s a matter of recognizing how seemingly disparate elements are connected. Consider the museum’s Hall of North American Wildlife, for example. Given its name, it’s no surprise that its primary focus is on the animals. But Tonsor wants visitors to take in the bigger picture—the plants, the rocks, the insects, even the things you can’t see, like the microbes. That’s the ecosystem, and that’s what enables the animals to survive.

And that’s what intrigues Rosenfeld. “I’m fascinated by how chemistry and biology interact in the natural environment,” she says. “There are millions of microorganisms in the soils beneath our feet. I study how pollutants and nutrients behave in the environment and the effect microbes have on soil and water quality.”

One of her current projects involves testing the potential for fungi to remove toxins from acid mine drainage.

Travis Olds and Carla Rosenfeld both do fieldwork underground. Above, Rosenfeld and a colleague sample copper and aluminum minerals and associated microbes in the Soudan Mine in Minnesota. Below, Olds poses in front of a seam of uranium ore where leószilárdite was found, a new uranyl carbonate mineral. It was able to form because humans mined the ore, allowing water to oxidize it and leach uranium from it.

Born and raised in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, mines are near and dear to Olds’ heart. Upper Peninsula mines have been operating for some 200 years, and a large share of the billions of tons of iron and manganese they yielded found its way into Pittsburgh steel.

Olds is particularly intrigued by radioactive minerals, the ones containing uranium and thorium. “The atomic arrangement and properties of uranium minerals are good analogs for advancing mining and processing, as well as the storage of used fuel and waste in nuclear power generation,” he explains.

New scientists, new areas of research, and new possibilities for collaboration.

Meaningful change, however, requires an understanding of the past, and that’s especially true when considering the museum’s exhibits.

Back to the Future

In the late 1800s, the world was still a mysterious place full of strange-looking rocks, plants, animals, and people—at least through the eyes of most Westerners.

Since many citizens of that era were unlikely to travel far beyond their own backyards, a new kind of public institution—the natural history museum—was created to bring the world to them.

Officially opening its doors in 1895, Carnegie Museum of Natural History did just that. The mission seemed clear, undeniable. If you fill the galleries with wonders and curiosities—from dinosaur fossils to Egyptian artifacts, birds of different feathers to African wildlife—the public will come.

Since then, priorities have shifted, perceptions and research have evolved, and environmental problems have escalated. The world has changed in ways unimaginable a century ago. That reality has prompted natural history museums to redefine their very reason for existing.

It starts with the name itself.

“‘Natural history’ is an antiquated phrase that we need to unpack,” Tonsor says. “In some ways, many of our collections are like mausoleums showcasing remnants of Western, white, patriarchal, colonial power.”

Case in point: the Lion Attacking a Dromedary diorama. Tonsor acknowledges that this popular display depicting a very dramatic scene of a lion, a symbol of French colonial power, attacking a person of color is a beautifully crafted work of art and certainly one of the most memorable in the museum’s collection. However, the display of unidentified human remains within the human figure is a major ethical issue and the portrayal of violence against a person of color perpetuates desensitization to such violence. Even the display’s landscape—a desert scene of ferocious drama—fits into a colonial view of North Africa. While in 2016–2017 the museum went to great lengths to reinterpret and rename the storied exhibit, it failed to address the fact that it’s fictional, and historically and culturally inaccurate.

For now, the display is curtained off from public view as Tonsor, with a cross-disciplinary team of staff, grapples with how to communicate to visitors a clearer explanation of the diorama’s troubled context and content. Exactly how a museum goes about the broader task of decolonizing is a topic of much debate. Generally speaking, the process involves moving beyond the dominant culture’s “ownership” of museum collections and interpretations by deconstructing what that ownership meant and its impacts, as well as elevating diverse voices, ways of knowing, and experiences to provide greater context, richer nuance, and alternative worldviews.

“We want to be inclusive,” Tonsor says, acknowledging the need to address all of the museum’s cultural halls, a priority that has become even more urgent in this moment of renewed demands for racial justice. “We want this to be a comfortable place for uncomfortable conversations.”

As far as he’s concerned, the conversations are just getting started.

“We’ve been contemplating not only what it means to be a natural history museum in the 21st century, but also what it means to be human, to be inextricably linked to nature.” – Stephen Tonsor, interim director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History

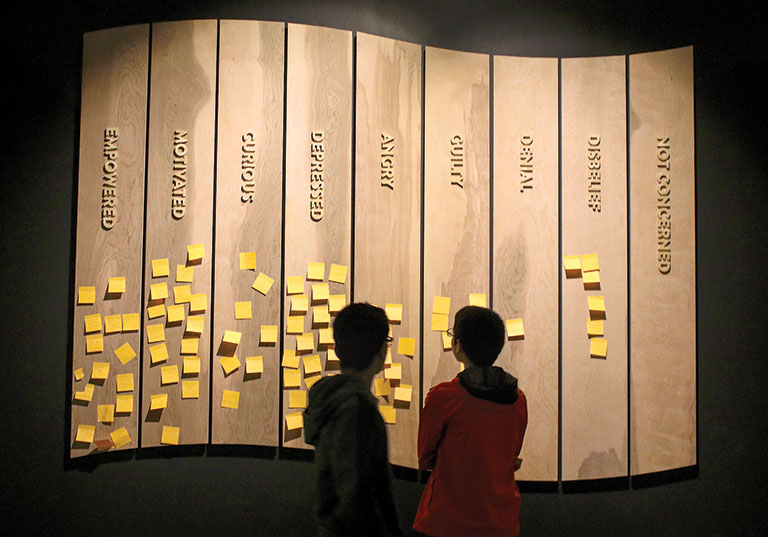

The museum’s recent We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene exhibition was the first of its kind in North America. It turned the lens on humans as a species to be studied and was designed to be participatory, offering visitors areas to reflect.

“In the 20th century we saw our advances as triumphs,” Tonsor says. “Well, as we now know, those triumphs were accompanied by unintended consequences.” Fossil fuels are a great example. When geologists discovered that there were vast deposits of carbon compounds from ancient life trapped in the rocks beneath us, the Industrial Revolution began. So much of what makes life comfortable for so many people results from harnessing the energy stored in fossil fuels. Their use literally changed the world. But even if we stop burning fossil fuels today, their effects on atmosphere and climate will be around for millennia to come—the melting of polar ice and displacement of low-lying populations, desertification of other regions resulting in loss of food production and massive wildfires.

So, what is the role of a natural history museum in this brave new world we’ve forged? “We want to take what we’ve learned by looking backward and apply it toward an intentional future,” Tonsor says.

Even if that future seems precarious.

“We’re not interested in creating an environment where visitors leave the museum thinking we’re all doomed,” Tonsor continues.

“We want people to understand the challenges and responsibilities we all have. We want them to feel fully a part of nature and to love their place in the earth’s great living system. We want them to feel hope that we can create a just and sustainable world to live in.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature