Trevor Paglen throws himself into James Bond-like adventures to make art that exposes mass surveillance and its impact on society. He’s a disrupter, shining his camera on those who secretly watch us, documenting what invisibility looks like.

He tracked drones high in the sky and learned to scuba dive to photograph government-tapped fiber-optic internet cables resting deep in the ocean. He chartered a helicopter to capture the rarely photographed National Security Agency headquarters in Fort Meade, Maryland (he called and gave the NSA a heads-up, asking them not to shoot). He uncovered secrets behind facial recognition software, which creates pictures we never see and makes conclusions we can’t dispute.

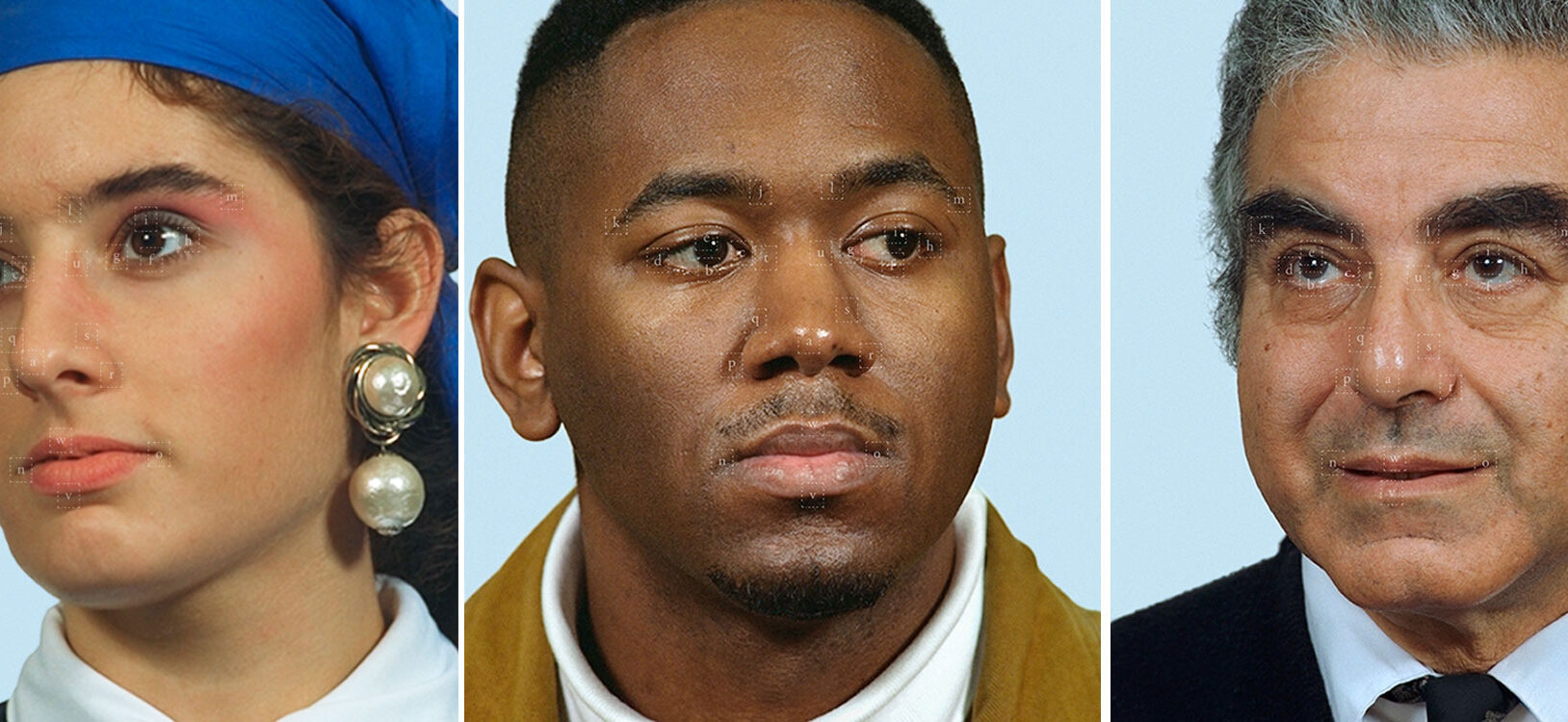

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead… (00520 1 F), 2019, inkjet print ©️ Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

To create facial-recognition software, computer scientists and software engineers need large collections of faces as “training images.” Before the advent of social media, a common source of faces for this research came from mug shots of accused criminals. Trevor Paglen ran the faces through facial recognition software and the lines that are drawn on top are markers of that software.

As much an investigative journalist as an artist, in 2017 Paglen was awarded the MacArthur “Genius” Grant for his provocative artworks at the intersection of photography, artificial intelligence, and mass surveillance.

Paglen’s art investigations reveal the utter fallibility and human biases behind computer vision. “There is an elaborate relationship between photography and power,” he says. “To what extent is power embedded in computer vision systems used to target weapons, for example, or to create algorithms that do profiling for law enforcement?”

His latest exhibition, Trevor Paglen: Opposing Geometries, is on view at Carnegie Museum of Art through March 14, 2021, as part of the museum’s Hillman Photography Initiative (HPI), a project that explores new ideas about photography. The questions Paglen’s work surfaces are urgent and timely, says Dan Leers, the exhibition’s organizer and curator of photography at Carnegie Museum of Art.

“There is a simultaneous increase in surveillance and a decrease in people’s perception of surveillance. There isn’t a police officer standing on the corner anymore. In a very artistic and emotionally grounded way, Trevor helps people understand that.” – David Danks, technology and society scholar at Carnegie Mellon University

“This exhibition has become even more relevant because of what is happening in the world right now,” says Leers. “Whether it’s policing Black Lives Matter protests or recording body heat as part of COVID-19 screening, cameras and computers are watching us at every turn.”

Paglen’s work alerts people to that pervasiveness of surveillance—in stores, in the office, and on the streets.

“Artificial intelligence is making it possible for governments to do surveillance on a scale never seen before, but it’s also less visible,” says David Danks, chief ethicist of Carnegie Mellon University’s Block Center for Technology & Society, co-director of the school’s Center for Informed Democracy and Social Cybersecurity, and a collaborator for this latest iteration of HPI. “There is a simultaneous increase in surveillance and a decrease in people’s perception of surveillance. There isn’t a police officer standing on the corner anymore. In a very artistic and emotionally grounded way, Trevor helps people understand that.”

Trevor Paglen, CLOUD #902 Scale Invariant Feature Transform; Watershed (detail), 2020, dye sublimation print © Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

Inside the front entrance of the museum hangs a large, site-specific mural created by Paglen of a cloud-covered sky. His choice of content—clouds—has a dual meaning: the white fluffy objects seemingly floating above us and virtual servers used to store data—a convenient, ubiquitous system but one susceptible to hacking. To the mural, Paglen applied an algorithm, a mathematical technique that allows machines to recognize objects. His project soon revealed that the algorithm doesn’t always get it right. Sometimes it misidentifies random swirls in the clouds as circles and other geometric shapes.

“How is a machine seeing circles in this image? That’s crazy,” Paglen says. “But you can take that further and say, ‘Does that mean we have this incredibly complex image and it’s been reduced by a computer to a series of circles? What are the implications of building tools that flatten out experience and flatten out history and flatten out personalities?’ You are taking a very complicated world and reducing it to something that is intelligible to a computer.”

The installation shatters the notion that computer-generated algorithms are a reliable version of the truth—in, say, distinguishing innocent faces from those of criminals. “We think computers are objective truth machines that reflect reality back at us,” Leers says. “But there is so much more to life than one algorithm can capture.”

Understanding the AI Brain

The implicit bias of artificial intelligence was evident in a 2019 project by Paglen titled ImageNet Roulette. The concept was simple: People could upload photos of their faces to a database to see how they were categorized by facial recognition software. Some of the labels were offensive, including “trollop” and “loser.” Many people of color noted an obvious racist bias to their results. The project, co-created with Microsoft researcher Kate Crawford, went viral and laid bare the pitfalls of computer-generated algorithms that unfairly label groups of people. The project drew on more than 14 million photographs included in ImageNet, a database developed in 2009 by researchers at Princeton and Stanford and widely used to train artificial intelligence systems.

“How do photographs, coupled with things like facial recognition, computer vision, and artificial intelligence, amplify certain kinds of power and economic interests at the expense of other kinds of social and economic interests?” Paglen asks. “For example, what is facial recognition software and who does it serve? Well, it mostly serves cops. It’s looking at these systems and understanding that they are political systems that weigh power in certain places and people at the expense of other people.”

It reveals how bias, racism, and misogyny are simply transferred to the technology. And it’s a powerful reminder of how our images are not only captured without our consent, but that the constant categorization of people can be dangerous.

Trevor Paglen, It Began as a Military Experiment (detail), 2017, 10 inkjet prints ©️ Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

The artist selected 10 photographs from a database of thousands of images taken of military employees in the mid-1990s and used to develop Facial Recognition Technology (FERET) by the U.S. Department of Defense. Faint letters mark the corners of each person’s eyes, nose, and lips. By comparing the physical features of many different faces, an algorithm could be taught how to “see” and identify individuals. Before social media, Trevor Paglen shows us, military research had already begun to create ever-growing data sets that could power systems of surveillance.

Similarly, the exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art includes a series of photographs of faces, as well as landscapes from the Old West. The work shows how artificial intelligence analyzes and labels them in ways that can be harmful.

“The world is messy and complicated,” says Leers. “It’s not going to fit into nice and neat categories. Humans can be more flexible. Computers are not. It’s the rigidity that leads to the kind of mistakes that can be problematic.”

“Through [Paglen’s] artistic efforts, he shows how difficult it is to watch those who are watching us.” – David Danks, technology and society scholar at Carnegie Mellon University

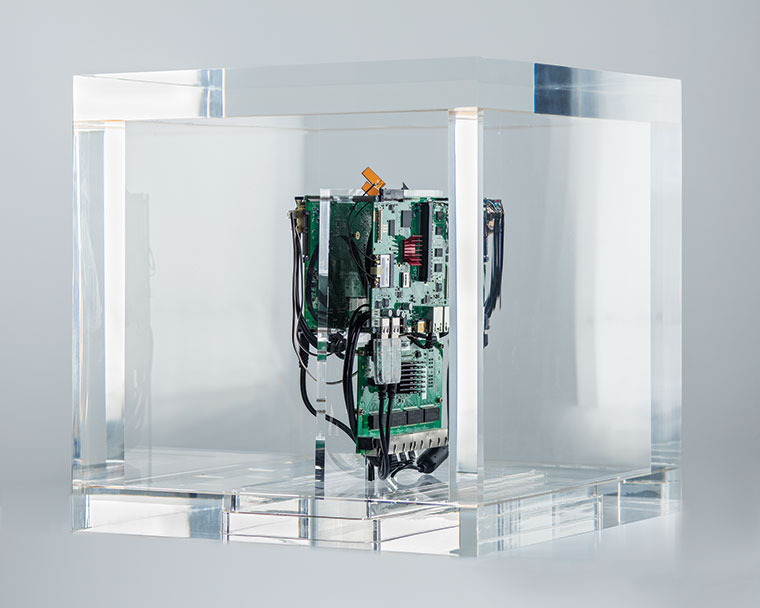

In the museum’s Modern and Contemporary Galleries, visitors can connect to a minimalist sculpture that Paglen calls the Autonomy Cube. Comprised of a computer motherboard encased in plexiglass and perched atop a pedestal, not only is it an elegant piece of art, it allows people to hop on the internet via Tor, a network that allows for anonymous browsing and prevents any kind of tracking.

Trevor Paglen, Autonomy Cube, 2015, plexiglass box, computer components ©️ Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

“He’s trying to raise awareness that as soon as you open a web browser, your online movements are being traced,” Leers says. “This artwork provides a safe space. The transparency of plexiglass holding the innards of a computer is a metaphor for how Paglen seeks to pull back the curtain on ‘big data’ and disrupt the surveillance state. Disruption is a great word when talking about Paglen’s work.”

Mapping Secret Places

Not surprisingly, Paglen took a nontraditional path as an artist.

After earning a master of fine arts degree at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2002, he weighed his options. He figured he could go the starving-artist route and work a minimum-wage job in New York City or go back to school. He opted for a Ph.D. “In graduate school, you get paid the same as working at 7-Eleven and you get to read books, instead of slinging Slurpees,” he says.

Paglen returned to the University of California–Berkeley, where he had received his bachelor’s degree, to study geography. Hardly a typical field for an artist, it fascinated him and changed the way he looked at the world. Already steeped in science-based art, he wanted to do science that would pass scrutiny. “I wanted someone in the field to be able to look at it and say, ‘Yes, that is research at the highest level possible, not some kind of amateur version.’”

Photo: Bryan Conley

“What are the implications of building tools that flatten out experience and flatten out history and flatten out personalities? You are taking a very complicated world and reducing it to something that is intelligible to a computer.” – Trevor Paglen;

The expansiveness of the subject also appealed to Paglen. “You can do almost anything with geography,” he says. “People have their own definitions of it, but to me, it’s the study of how humans change the surface of the earth.”

In the 1990s, as the number of prisons grew, he worked with activists on preventing new prisons from opening in California. “I was a prison abolitionist,” he says.

His art focused more on government secrecy after September 11, 2001, when the government declared a “war on terror.” Paglen turned his attention to Guantanamo Bay and “black sites,” the secret prisons the CIA set up in Afghanistan and other places around the world. To track down the Salt Pit, a notorious prison northeast of Kabul, he used commercial satellite imagery. He talked to former prisoners, even using one of their maps to zero in on the location.

He also tracked down secret military bases. The son of an Air Force ophthalmologist who was born on Andrews Air Force Base, he knew the right questions to ask. “I knew how to talk to people. I knew the language, the culture, and it opened a lot of doors.”

Trevor Paglen, Near Tahoma Circle Hough Transform, 2020, albumen print ©️ Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the artist and Altman Siegel, San Francisco.

Returning to iconic western landscapes captured by his predecessors, Trevor Paglen translates his 8-by-10-inch negatives into digital files that can be read by artificial intelligence (AI). He then overlays lines, circles, and strokes that signify how computer vision algorithms attempt to “see” by creating mathematical abstractions from images.

Paglen photographed places we aren’t supposed to see—such as the National Reconnaissance Office Ground Services Station in Jornada del Muerto, New Mexico. The base is tucked away deep in the desert and surrounded by restricted lands, and he managed to photograph it using the kind of high-powered telescope that astronomers use to look at stars.

Going to such extreme measures to make art is another part of his unsettling message. “Through his artistic efforts, he shows how difficult it is to watch those who are watching us,” Danks says.

Cameras at Every Crosswalk

In recent years, as large tech companies such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon began collecting data, Paglen began asking questions about how that information is used. “You have these massive global infrastructures ingesting information,” he says. “How is that information interpreted?”

All the issues of Big Brother-like surveillance are heightened during the coronavirus pandemic, as socially isolated people are forced to use technology to connect. “The only way that we can be sociable with each other right now is by using platforms that are designed to extract as much information as possible about us and use that information ultimately against us,” Paglen says. “There are newer versions of online productivity software. There’s tools that try to measure your eyes and attention, trying to quantify your productivity.”

Other applications, he notes, are used in places like call centers to try to capture employees’ faces and measure their emotions as they interact with customers. “Are you happy? Are you confused? Are you sad? Are you fearful? Are you surprised? They are trying to ensure and quantify the degree to which you’re emoting in the kind of proper way that the company wants you to.”

Trevor Paglen, “de Beauvoir” (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) Eigenface (Colorized), 2019, dye sublimation print ©️ Trevor Paglen. Courtesy of the artist and Pace Gallery.

Paglen’s portrait of the late philosopher Simone de Beauvoir captures her facial “signature” created by the most sophisticated AI software.

The documented surveillance of Black Lives Matter protesters raises new concerns about policing, as voiced by elected officials and the American Civil Liberties Union. News organizations have reported that police are using Amazon’s Ring doorbell cameras, facial recognition technology, powerful infrared and electro-optical cameras mounted to the wings of planes, drones, and other military-grade technology to perform surveillance on both protesters and journalists.

To critics who say that police surveillance keeps criminals behind bars, Paglen professes that efficiency is not an ideal thing in law enforcement. “As a society, sure, we can put every single resource into law enforcement. We could actually have far less lawbreaking if we wanted to, because having cameras on every crosswalk means that every single person who jaywalks could get a ticket. There’s systems that do that in China, for example.”

His art shines a light on issues that people in authority would prefer to keep hidden.

“I make art so that I can teach myself how to see differently,” says Paglen. “I feel like by learning how to see differently, we can question the assumptions we have about how we think the world works and think about how the world might look different.”

Generous support for the Hillman Photography Initiative is provided by the William T. Hillman and the Henry L. Hillman Foundations.