Avonworth junior Emelia Houser says she’s “not the best” at history. As a creative thinker who likes to work with her hands, it’s the rote memorization and constant note taking, she says, that trips her up. But it’s clear from the video Houser created—her first ever—for a class assignment on imperialism that she has a real knack for the storytelling that brings the complexity and humanity of history to life.

In her short video, black-and-white clips of life in Egypt in 1882 appear—people in a busy market, ship traffic on the Mediterranean—then Houser’s hand emerges, and using a brush she slowly blacks out these once peaceful moments with paint.

“It’s showing what the British invasion took from the people of Egypt, in trade, in freedom of religion, to devastating effect,” says Houser, noting that she worked on a related essay as she developed the video. “We spent weeks researching what interested us, and learning people’s stories, instead of just memorizing a bunch of facts for a test. I chose to make a video to convey the emotional parts of imperialism.”

Her inspiration came during a class trip to Carnegie Museum of Art as part of her integrated art, world history, and language arts course. A trio of teachers partnered with museum educators on how to make the best use of the museum’s strengths—a vast collection and a dedicated group of educators to help activate it—as a key component of the course’s curriculum and months-long culminating project.

“Our visit to the museum deepened the students’ understanding of imperialism,” says world history teacher Molly Chester, who co-teaches the elective offering. “They learned how artists play a role by using their voice. It also opened the students’ eyes to different mediums and materials. We want them to be open and take risks with their projects.”

For Houser, it was conceptual artist Alex Da Corte’s contribution to the Carnegie International—an epic neon house filled with pop culture and cartoons inside the Heinz Galleries—that made a lasting impression.

“His videos are so abstract. You really have to watch them, sometimes more than once, to see how much there is to them,” she says. “I thought they were so interesting. They inspired me to try video.”

Personalizing the museum experience

Museum educators working collaboratively with teachers and students to personalize their project-based museum experience is an ongoing experiment appropriately titled Create Your Museum, made possible through generous support from The Grable Foundation. Especially meaningful, says Nina Unitas, coordinator of visual arts and design in the curriculum office of Pittsburgh Public Schools, is having the repeat presence of museum educators in area classrooms.

“Many kids don’t naturally see themselves in the museum, but when you bring the museum staff to their school and there is a multiple-day connection—it’s like, ‘hey, we can connect to you in our environment.’ It’s very powerful,” says Unitas. “The museum isn’t just a place; it’s connected to humans we’ve had contact with, who care enough to come and spend time with us in our school.”

Museum educator Valerie Herrero talks art and empathy with fourth graders at Beechwood Elementary. Photo: Bryan Conley

“Many kids don’t naturally see themselves in the museum, but when you bring the museum staff to their school and there is a multiple-day connection—it’s like, ‘hey, we can connect to you in our environment.’ It’s very powerful.”

– Nina Unitas, coordinator of visual arts and design in the curriculum office of Pittsburgh Public Schools

In the 2018–19 school year, nearly 800 students from 13 schools participated in the prototype program. Five of the schools, including three Pittsburgh Public Schools fourth-grade classes, benefited from multiple-session experiences, including classroom visits—allowing time and space for students to build a relationship with museum educators and the art. The remaining schools focused on a single museum visit. While it’s a serious time commitment for museum staff to work with area teachers to personalize museum experiences, it’s proving to be a game changer in meeting the needs of local schools, and the hope is to scale it over time.

“We went into the project assuming we would need to make a case for the value of museum arts education,” says Laurie Barnes, museum educator and program manager for school groups. “We were wrong. The audiences we serve already know we possess valuable resources—they just don’t know all the ways they can make use of them.”

This collaborative, multiple-session approach is working to change that. In some cases, the schools know exactly what they want.

For fourth graders in Pittsburgh Public Schools, reading and writing is a main focus, so museum-led curriculum has focused on reading images like text, which involves lots of close looking and visual thinking.

Students and museum educator Laurie Barnes team up for close looking in the galleries.

“How do we make it so the museum is something they need in their lives, that is essential to their learning?”

– Tim Kunze, the museum’s community educator

“We explore how an artist creates tone, mood, and setting similar to how a writer does,” says Tim Kunze, the museum’s community educator. It’s more fun than it may sound, with museum docents encouraging students to imagine dialogue between characters in a painting, or letting students explore a gallery scavenger hunt-style as a way to think more closely about place and character choices. Overheard during many of the school gallery visits is docents asking students: “What do you see that makes you think that?”

“Once they make that connection between artist and writer,” continues Kunze, “we hope they can do better on their exams and also apply it to real life, to other circumstances. What we’re really trying to figure out is how do you measure meaningfulness—for teachers, for students. How do we make it so the museum is something they need in their lives, that is essential to their learning?”

Remembering through art

With an energetic fourth grade class, Beechwood Elementary teachers Tish Rygalski and Kellie Spinneweber identified building empathy as a key goal of their project, along with exploring the idea of what’s worth remembering and preserving.

“We had a very chatty group and the kids were always talking over each other,” says Rygalski. “We wanted to focus on the idea of respecting each other’s opinions, taking time to listen to others. And we wanted our experience at the museum to reflect the idea that art can be about everyday things—feelings you may have, memories you may hold.”

During the group’s tour of the Carnegie International, the students kept returning to ideas centered in the miniature sculptures of Japanese artist Yuji Agematsu, which he pieces together from the tiny leftovers of life found on the streets during his daily walks in New York City—used chewing gum, dental picks, dead bugs, cotton swabs, candy wrappers. Back in his studio, he assembles the day’s finds within cellophane sleeves stripped from cigarette packs and groups the tiny terrariums together by month.

Time capsules created by Beechwood fourth graders.

“His work led to questions about who gets to make art. What’s trash and what’s not? The students were interested in the idea that Yuji took trash and turned it into something else,” says Valerie Herrero, one of the museum’s school programs instructors. She co-led seven visits with the class—three at the museum and four in their classroom, where they created individual Yuji-inspired time capsules to store favorite memories from fourth grade. At the end of the project, the students joined together to create a group installation of their time capsules.

Gathered in a half-circle around the front of their classroom, Herrero prompts students. “Tell us something that you’re keeping that is unique to you. Something you want to remember from fourth grade,” she asks.

“This is the first fish I ever caught with my papa and dad,” says 10-year-old Alexis, showing off a small fish she sculpted from clay to be included in her time capsule.

Waiting patiently for his turn, Jonathan is up next. “This is Conan O’Brien,” he says, holding up a head he sculpted for all to see. “When I grow up I want to host a late-night talk show and tell jokes.”

Inspired by Noah Davis’ painting depicting a neighborhood known as “Black Wall Street” and the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, Avonworth students collaborated on a work featuring the 1965 Watts Riots, an urban rebellion similarly withheld from history books.

Who is not represented?

No doubt, museum visits inspire area teachers, too.

Ryan Kelly’s eighth grade American history classroom at Quaker Valley Middle School was decorated the way one might expect: with American flags, historical figures, famous speeches, and a list of the U.S. presidents. What was missing were less celebrated but no less important figures. It’s an oversight Kelly and his teaching colleague had been contemplating together with museum educators, who introduced them to the work of Nassau-born artist Tavares Strachan circling the outside of the museum.

When Andrew Carnegie gave the massive sandstone museum building to the city of Pittsburgh in 1895, the names of Aristotle, Darwin, Leonardo, Mozart, and other accomplished men of literature, science, art, and music were etched into the fascia. In 2018, as part of Carnegie International, between the names of these famous figures, Strachan installed, in glowing neon, the names of 54 artists, scientists, explorers, and other innovators whom the artist didn’t want to slip through the cracks of history.

Among these revolutionaries: Qiu Jin, a feminist poet who became known as “China’s Joan of Arc”; Sister Rosetta Tharpe, a queer black woman from Arkansas who was the godmother of rock ’n’ roll and the first gospel-singing sensation; and Cécile Chaminade, a prolific and much celebrated French composer and pianist. The expression was an extension of the artist’s Encyclopedia of the Invisible, a well-researched list of people, places, and things society has forgotten over time, some 2,800 pages worth and counting.

“We immediately wanted to know how could we do that—make a location-based work at school and take on Tavares’ role,” says Kelly, “to bring to light figures in our history not traditionally discussed. We wanted to know whose stories the students think should be told and illustrated in our classroom.”

“The question at the core of our discussions was who is represented and who is left out? Some people question if eighth graders can handle these kinds of conversations. They can.”

– Ryan Kelly, American history Teacher at Quaker Valley Middle School

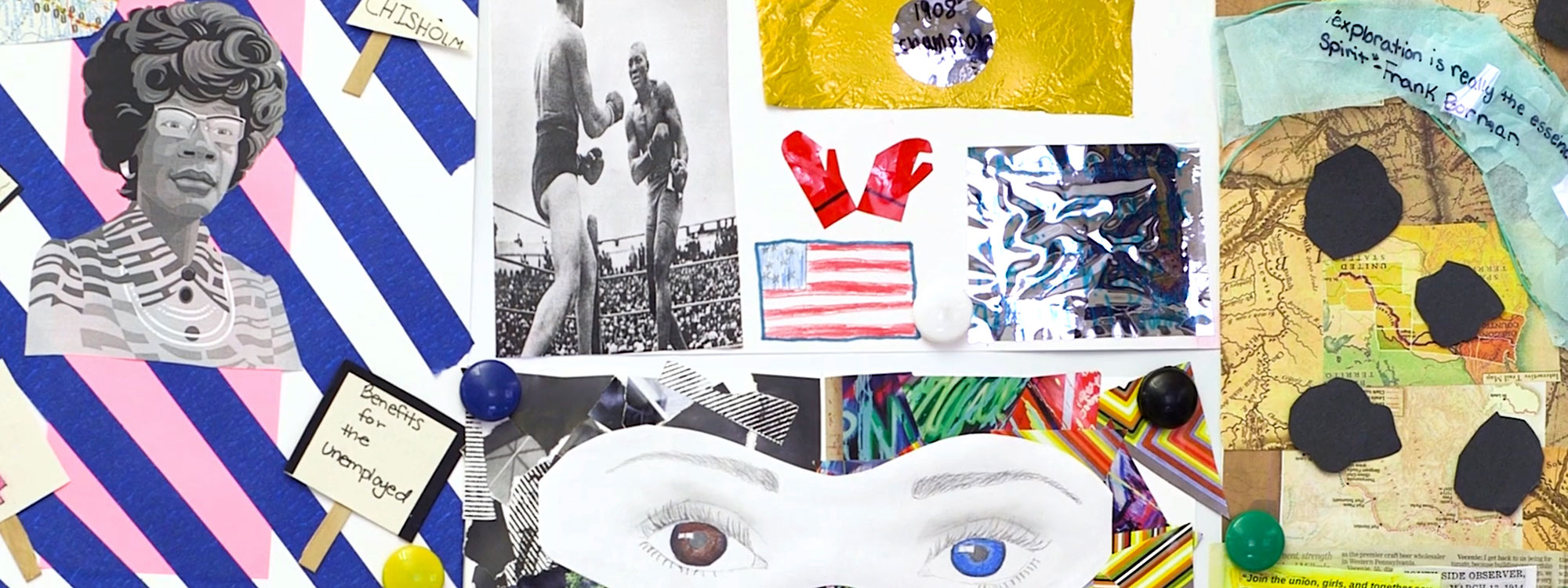

Inspired by the work of artist Tavares Strachan, Quaker Valley eighth graders created portraits of figures from history who they decided should be represented in their classroom.

To start the project, the students visited the museum, and then a pair of museum educators joined them in their Quaker Valley classroom for four additional sessions. Working in groups of four, the students conducted research and created portraits and accompanying essays of their own “invisible” figures.

“The question at the core of our discussions was who is represented and who is left out?” says Kelly. “We, as schools, the Carnegie, as a museum—these are conversations we’re engaged in, with students, with parents, with patrons. Some people question if eighth graders can handle these kinds of conversations. They can. They speak very clearly about it and provide examples from the world, from their own lives. And they applied this thought process to other projects as the year went on—How can they include additional voices in research, what kinds of sources can we look at as a class that are not as commonly referenced?”

Among the portraits added, front and center, to the walls of the group’s classroom: Misty Copeland, the first black female principal dancer with the American Ballet Theatre; soul legend Sam Cooke; and Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to the U.S. Congress.

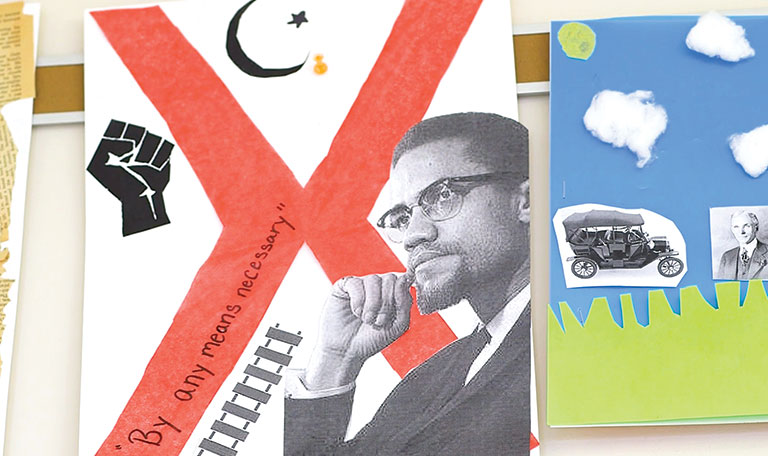

On display day, Kelly asked students to select a meaningful place in the classroom where their tribute should be hung. The group who researched Malcolm X suggested that his portrait hang near the classroom door.

“One of the students said, at the beginning of the year, you told us, when we enter this room, we’re all equal. This is our shared space,” recounts Kelly. “‘I want to put Malcolm X by the door. I want people to think about that statement when they enter and when they leave class.’”

The Create Your Museum program is generously suported by The Grable Foundation.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Art