Crowding the sidewalks outside and filling the pews within, the faithful and the skeptics gathered at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City on April 1, 1987. Their common purpose was to bear witness to Andy Warhol’s memorial service.

Predictably, the scene that unfolded in Midtown Manhattan that chilly spring day had all the trappings of a true Warholian extravaganza.

There were celebrities. The 2,000-plus guest list included the beautiful (Bianca Jagger, Grace Jones, and Raquel Welch); the fashionable (Diane von Furstenberg, Halston, and Calvin Klein); the avant-garde (Robert Mapplethorpe and Yoko Ono); the stars (Richard Gere, Don Johnson, Liza Minnelli); and the Superstars (Baby Jane Holzer, Gerard Malanga, and Ultra Violet).

And there was a sense of tragedy. Having survived a near-fatal shooting almost 20 years earlier, Warhol’s death due to complications from gallbladder surgery was shocking.

But perhaps the biggest shock of all was delivered by art historian and critic John Richardson, who in his eulogy recalled a spiritual side of the Pop icon’s character that was mostly kept under wraps. “Those of you who knew him in circumstances that were the antithesis of spiritual may be surprised that such a side existed. But exist it did,” Richardson proclaimed, “and it’s key to the artist’s psyche.”

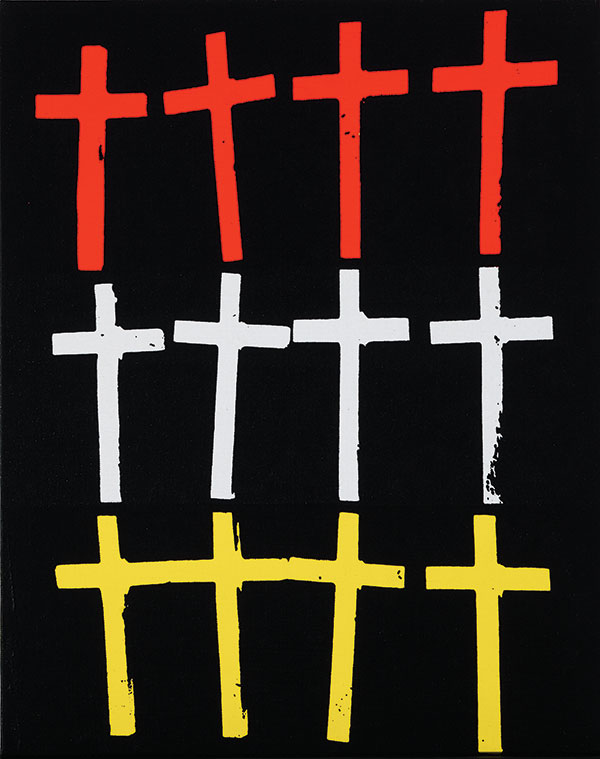

Andy Warhol, Crosses, 1981–82

“Those of you who knew him in circumstances that were the antithesis of spiritual may be surprised that such a side existed. But exist it did, and it’s key to the artist’s psyche.”

– John Richardson, art historian and critic

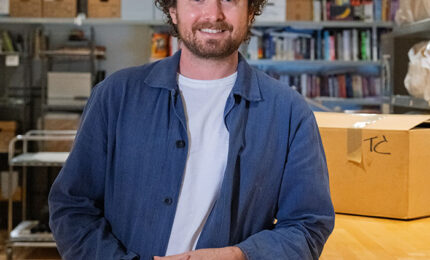

Donna De Salvo remembers the moment. The former longtime chief curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art would go on to steward five Warhol-themed exhibitions, including the recent critically acclaimed Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again. But in 1987, it was the Hollywood-like fanfare that captured her attention.

“I was a young curator and I was just honored to have been invited,” she says. “I was in awe watching all the celebrities and famous people coming in. It was very grand.”

Richardson went on to disclose how Warhol, a regular churchgoer, would often serve meals to the homeless at a local shelter, and was proud to have been able to help pay for his nephew’s seminary studies. Paul Warhola, or Pauly, as the son of Warhol’s oldest brother was known to the family, did become a priest, but ultimately renounced his vows to marry a nun.

“The knowledge of this secret piety,” Richardson continued, “inevitably changes our perception of an artist who fooled the world into believing that his only obsessions were money, fame, and glamor, and that he was cool to the point of callousness.”

It turns out that the signs, symbols, and imagery from Eastern and Western Catholicism were hiding in plain sight all along. But as with all things Warhol, it’s complicated.

The sacredness of everyday culture

“We know that Andy Warhol takes visual language from contemporary culture and re-presents it, and that includes religious content,” says José Diaz, chief curator of The Andy Warhol Museum. “Warhol repeatedly appropriated images from Catholic visual culture and reinterpreted them in the context of Pop.”

That fundamental principle is the guiding force behind Andy Warhol: Revelation, the first exhibition to exclusively explore the connection between Catholicism and his body of work. Curated by Diaz, it will debut at The Warhol on October 20, and next spring it will travel to the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Kentucky.

“Warhol repeatedly appropriated images from Catholic visual culture and reinterpreted them in the context of Pop.”

– José Diaz, chief curator, The Andy Warhol Museum

Featuring more than 100 objects from the museum’s collection and archive, Revelation will provide visitors with an opportunity to behold personal memorabilia, universally lauded masterpieces, and little-known commissions.

[URIS id=7439]

“I do think this show will be a revelation,” says De Salvo. “What’s very distinct is the access to the archival material that’s not available to other people, and certainly wasn’t available during Warhol’s lifetime.”

Not long after the artist’s passing, staff at The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (and, upon its founding in 1994, The Andy Warhol Museum) started sorting through and cataloging all the many things Warhol left behind, including his 610 Time Capsules. That work continues to this day. Most of the Time Capsules are cardboard boxes filled with newspaper clippings, day planners, bills, ticket stubs, handwritten letters—life’s detritus. For those seeking to better understand Warhol, they’re the holy grail.

By taking a deep dive into these archival materials, Revelation presents material clues of Warhol’s Catholic influences.

This includes family prayer books and prayer cards, as well as a chalkware plaster statue of Jesus on loan from the John Warhola family that Warhol painted when he was between 10 and 13 years old, taking great care to detail the crucifixion wounds on the hands of Christ and color the Sacred Heart a deep red. There are souvenirs from Pope Paul VI’s 1965 visit to New York City and mementos from Warhol’s 1980 visit to the Vatican, where he met Pope John Paul II in St. Peter’s Square.

But perhaps one of the more illuminating finds is the source material Warhol used for his Last Supper silkscreens. In 1984, a Greek gallerist named Alexander lolas commissioned Warhol to create a group of works based on Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper for an exhibition space in Milan located across the street from the home of the original. Warhol exceeded the demands of the commission and produced more than 100 variations on the theme. He died just a month after the Milan opening.

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (detail), 1986

Just recently, the archives staff at The Warhol found a perfect match between a “kitschy” circa 1980s cardboard reproduction of the The Last Supper and Warhol’s famous Last Supper silkscreen series. They attribute the image to German engraver Rudolf Stang (1831–1927), confirming that Stang’s 1888 rendition of The Last Supper was the true source image used by Warhol for these silkscreens—including Revelation’s showstopper, The Last Supper doubled and in pink, made in 1986. This particular iteration is more than 25 feet long, bold, and undeniable. In other versions Warhol overlaid the logos for Dove soap, General Electric, and Wise potato chips.

“Warhol understood the meaning of The Last Supper,” Diaz says. “He frequently encountered the image at his childhood church and home. In his works, Warhol not only contributes to the common consciousness of organized religion but also celebrates the sacredness in everyday culture, as experienced through advertising, film, and television,” Diaz says. “He treats Jesus as he would a movie star.”

Warhol’s faith is clearly on display in the exhibition. “We know that he was going to church throughout periods in his life; his diaries in particular record church attendance from 1976 to 1987,” Diaz says, noting that the diaries were published posthumously. “He would pop in and sit quietly in the back. Warhol embraced Catholicism on his own terms.”

Warhol was quite adept at compartmentalizing his life. He often traveled with an entourage, and most of the members of his inner circle were Catholic. Photographer Christopher Makos recalled in his memoirs, “[Andy] may have related better to us Catholics because we all have the same background: Mass, priests, nuns, Catholic school, a sense of guilt. His religion was a very private part of his life.”

He was out professionally as a gay man but chose to remain more closeted about his Catholicism. “It’s a very complex topic,” De Salvo acknowledges. “The challenge is how to tease out all the contradictions—all the collisions—within Warhol.”

“In his works, Warhol not only contributes to the common consciousness of organized religion but also celebrates the sacredness in everyday culture, as experienced through advertising, film, and television. He treats Jesus as he would a movie star.” – José Diaz

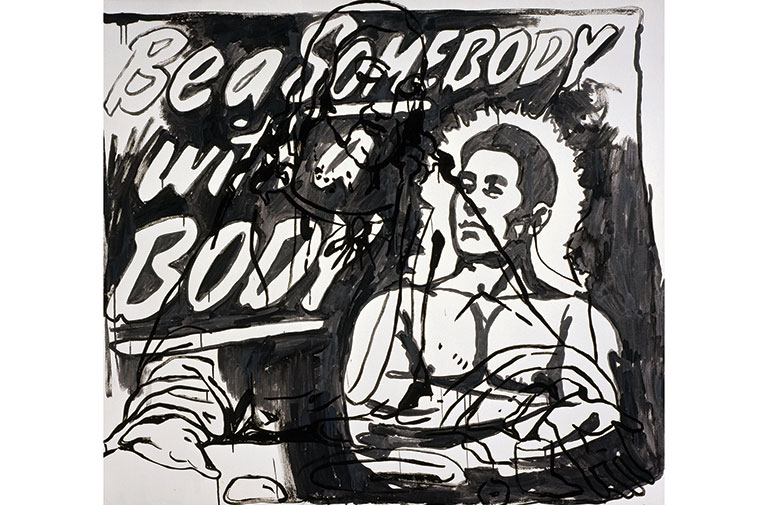

Those collisions, Diaz says, can be found in Warhol’s explorations of the body—its contours, fluids, and behaviors. “The Catholic imagination conflates sexual encounters with the presence of God,” Diaz says, “using passionate erotic love as a metaphor for God’s love. Think of depictions of Christ in Western art history. He’s this muscular man who’s practically naked hanging on a cross. There’s an element of eroticism, desire, perhaps a little bit of provocation. The artistic focus of the Renaissance intensified the mystification of the body, which continues to the present,” Diaz continues. “Warhol, as a queer Catholic man, was undoubtedly influenced by this carnal, even sexualized imagination, which explains why he created artworks that grapple with the body, queer desire, and holy figures.”

Andy Warhol, The Last Supper (Be a Somebody with a Body [detail]), 1985–86

By way of example, Revelation offers the flesh: Christ juxtaposed against a bodybuilder (The Last Supper (Be a Somebody with a Body [detail])). And the sanctified: a woman breast-feeding (Madonna and Child).

Church and community

Warhol’s Catholic influence truly begins with his family—and, more specifically, his mother.

“The public’s general sense of Andy Warhol is usually associated with his Silver Factory, Studio 54, soup cans, and Marilyns,” Diaz says. “We realized that people often don’t know that he was from Pittsburgh, that he went to church, and was the son of immigrants.”

Life was difficult, the Great Depression made sure of that. But the Warholas were true believers. They held fast to their Carpatho-Rusyn roots, immersing their sons Paul, John, and Andy in the culture, heritage, and religious traditions of their Eastern European homeland.

When Andy was 6, the family settled in the working-class neighborhood of South Oakland. The primary selling point for the modest Dawson Street duplex was its close proximity to St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church in lower Greenfield.

Sunday liturgies were never optional. And with the family sometimes attending four services in a single weekend, young Warhol spent hours and hours taking in the sights, sounds, and smells (of incense) within the church.

Original icon panels from Andy Warhol’s childhood church, St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church. Warhol would have seen the icon on his weekly trips to church.

John Hegedus, Saint Andrew, Saint Peter, ca. 1916–1919, Courtesy of St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church, Pittsburgh, PA

Looming large at the front of St. John Chrysostom was the iconostasis, or icon screen. Its function was to separate the altar from the pews, while its striking aesthetic reflected the old-world style of painted saints framed amid pastoral landscapes, an iconographic tradition brought over from Eastern Europe. Made of wood, its symmetrical construction called for the religious paintings to be displayed in rows, creating a serial effect.

Today, St. John Chrysostom is home to a different, more elaborate and gilded icon screen. But four panels dating back to 1916—the very same panels Warhol would have gazed upon as a child—will be on view in the exhibition.

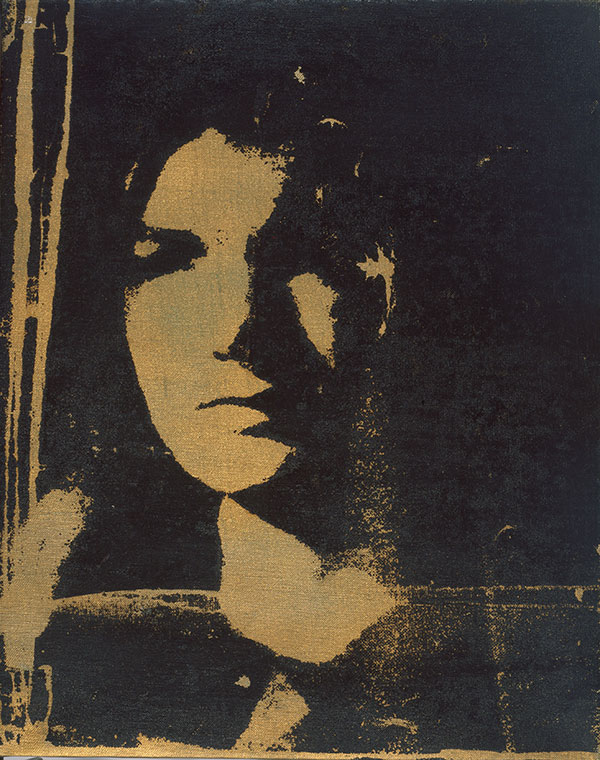

Donald Warhola, who serves as The Warhol Foundation’s vice president and liaison to The Warhol, sees the vividness of his uncle’s celebrity portraits reflected in the church’s original icon screen.

But there’s more to it than that, Diaz notes. “Warhol drew inspiration from these icon paintings and transformed images of celebrities into modern saints and gay icons. He takes the secular and turns it into the sacred.”

His Jackies, Marilyns, and other cultural denizens of the day—not unlike images of the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and St. Veronica—become worshipped figures.

Andy Warhol, Jackie, 1964

Sitting in church for great lengths of time was no doubt a transcendent experience for Warhol. “He was the consummate visual thinker,” De Salvo says. “He absorbed everything.”

And like so many experiences of his youth, Warhol’s mother was clearly in the picture. In addition to overseeing her son’s spiritual upbringing, she presided over his medical care when his various health issues kept him home from school, and she cultivated his creative growth.

An artist herself, Julia took note of her son’s God-given talent, encouraging him to participate in the Tam O’Shanter art classes at Carnegie Museum of Art. Even after the family patriarch died in 1942, the Warholas remained committed to Andrej’s hope that Andy would go to college.

That hope became a reality. In 1949, soon after graduating from Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) with a degree in pictorial design, Andy Warhola packed up his few possessions, moved to New York City, and as part of the nascent adman stage of his career dropped the “a” from his name.

Mama’s boy

According to Diaz, Warhol’s early years in New York provide the most obvious connection to his religious upbringing, and his mother. “During the 1950s, Andy was working as a commercial illustrator for clients like I. Miller Shoes, Cadillac, and Lord & Taylor,” Diaz says. “We have examples of his commissioned works on paper showing Nativity scenes and angels,” imagery he would have been extremely familiar with.

That’s no coincidence. Angels and cats, and sometimes holy cats, were Julia’s favorite subjects to draw. In 1952, she took her own leap of faith and not only moved to New York but also moved in with Andy. Far from cramping his style, Julia became his secret weapon, lending her cursive script to some of his commercial projects.

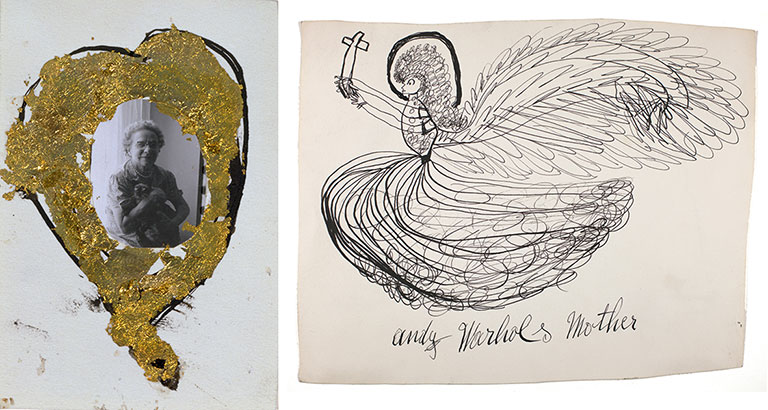

Above left: Andy Warhol, Julia Warhola, ca. 1957 Above right: Julia Warhola, Angel Holding Cross, created between 1952 and 1970

Mother and son shared a home for nearly two decades. And every morning, says Donald Warhola, “Uncle Andy and Baba [Julia] would kneel down and pray.” The pair also attended St. Mary’s Byzantine Catholic Church in Manhattan together.

It was during their New York years together that Warhol became a star. But even stars, and their mothers, are mortal. After surviving the assassination attempt in 1968 that left him scared and scarred, Warhol faced the death of his mother just a few years later in 1972.

Every morning, “Uncle Andy and Baba [Julia] would kneel down and pray.”

– Donald Warhola, nephew of Andy Warhol

It’s hard not to notice the theme of mortality lurking in Warhol’s work. There’s the Death and Disaster series and the Skull paintings, and there’s the subtler reel 77 of Warhol’s 25-hour film **** (Four Stars), which was originally made for his unfinished “sunset” film project.

Andy Warhol, reel 77 of **** (Four Stars) (“Sunset”), 1967

Commissioned in the summer of 1967 by Catholic art collectors John and Dominique de Menil, the sunset project was funded by the Catholic Church specifically for the 1968 world’s fair in San Antonio, Texas.

To meet the patron’s request, Warhol began traveling across the country in search of his ideal setting sun. He would stake out a location and then allow the camera to run uninterrupted, yet he never captured one that satisfied him.

In the end, the church opted not to participate in the fair. Warhol never completed the film, and what he did shoot has rarely seen the light of day, until now. Visitors to Revelation will have the opportunity to watch a section from Warhol’s sunset film footage, and view four Sunset prints, completed five years later and inspired by the film. Thirty minutes long, reel 77 focuses on one sunset on one summer day along the coast of California, and features the voice of the Velvet Underground’s Nico reciting haunting incantations.

“Sunsets,” Diaz says, “are spiritual in a very inclusive way of just being on this Earth. They’re symbolically tied to the transience of life and the certainty of death. Warhol understood the dichotomy between life and death.”

It is a distinction that became meaningless, at least for Warhol. But the artist’s unexpected death has left Diaz to ask what might have come after the Last Supper series.

“Who knows what he would have produced beyond that last body of work,” Diaz says. “He was able to take sacred culture and make it secular by using a lot of the same tools that religion uses. He made art that spoke to the masses.”

And who knows how the masses will respond to what they will see in Revelation. “We’re not trying to make Warhol into a role model,” Diaz says. “I don’t think anyone should come looking for religious guidance. I hope that people come in with an open mind!

“We are still finding new clues about the Catholic side of Warhol, and this will continue long after the exhibition. The goal of Revelation is to open the door on this complex and uncharted topic for future generations of scholars, curators, and Warhol enthusiasts.”

Andy Warhol: Revelation is presented by Bank of America and supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Fine Foundation.

All artworks by Andy Warhol, The Andy Warhol Museum © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.