It’s wood frogs that educator Jenise Brown likes to sneak into the curriculum she’s bringing to life for Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s summer camps and home-school programs. Mainly because most kids think frogs are icky and slimy. Gross. Not cool at all. Until they hear about the wood frogs. “They burrow under leaves in the winter and they can freeze solid, a frozen frogsicle, for the whole winter because of what’s basically antifreeze in their blood to keep their body from forming crystals in their blood cells,” she says. “In the spring, when it warms up, they just wake up and go about their lives. Everyone always thinks that’s such a cool thing. It’s a great way to get kids and adults excited about crazy animal adaptations.”

The idea that the natural sciences can be cool is the key to the curriculum taught by the museum’s team of 19 full- and part-time educators. “It’s not just for someone wearing a white lab coat,” says Brown, who graduated from the University of Pittsburgh with an undergraduate degree in biological science and a master’s in integrative biology from the University of South Florida. But even after getting published in top scientific journals and working with a roster of impressive colleagues, she felt frustrated.

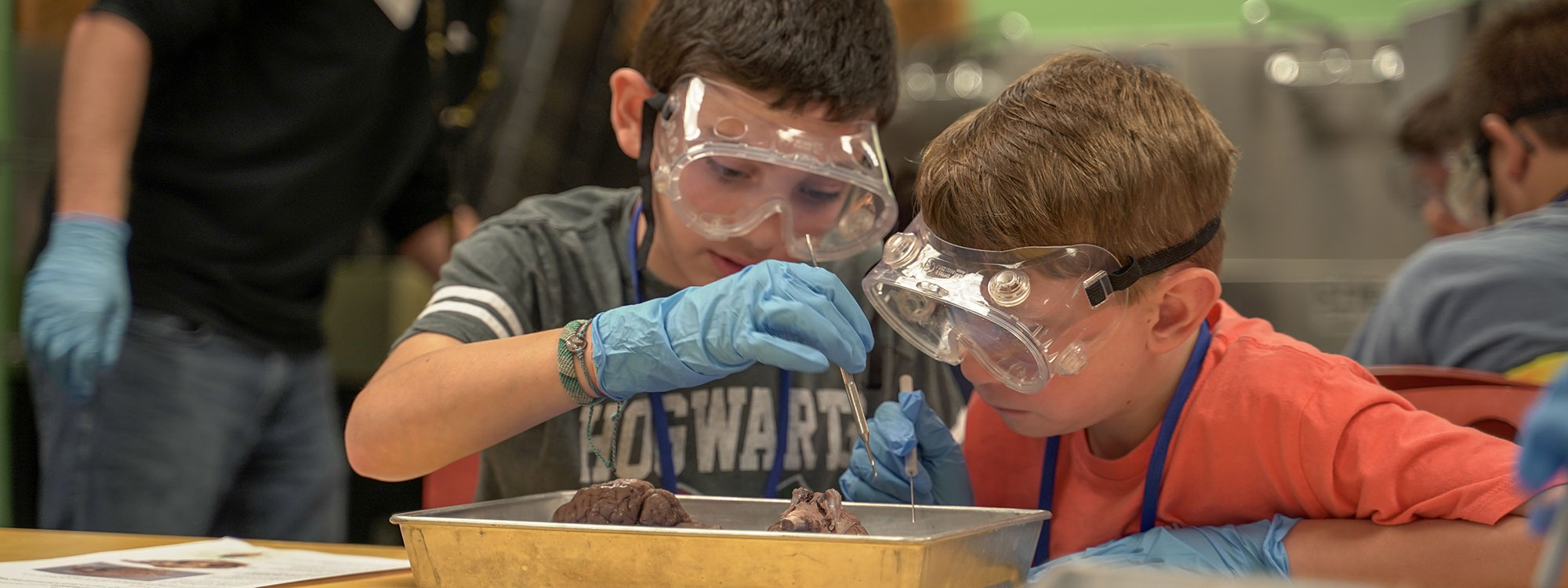

“I felt like I was doing science for other scientists,” Brown says. “My work wasn’t getting out to the public. It felt like it wasn’t making a broader difference.” It didn’t compare to the feeling she got from teaching kids, training them how to think like a scientist, to experiment, get their hands dirty. “To not take everything at face value,” she says. “We’re inundated with data and not necessarily trained on how to think through the process of whether something is real, as compared to 30 years ago, when information was verified. It’s scary. Especially for kids.”

“It wasn’t until I found myself knee deep in a tide pool that I thought, ‘Wow, biology is super cool!’”

– Educator Brandon Lyle

Museum educator Brandon Lyle had the same thought after someone casually recommended that he should stop eating pork. “They had watched a video on YouTube that claimed if you poured Coca-Cola on raw pork chops, worms would appear. And I thought, ‘That’s kinda ridiculous.’” But the video had gone viral, getting more than 4 million views. As the person responsible for having written 30 lesson plans in three years for the museum’s summer camps, home-school programs, and a new, family-based offering called Nature Lab, the experience inspired him to design a camp investigation titled “Internet Hoax?”

“The idea is that we watch the pork chop video, talk about what lines up with their own experiences, and then do the experiment ourselves so that the kids learn the concept of processing information, thinking about it, and drawing their own conclusions instead of just hearing something and saying, ‘Yeah, that sounds right!’” Lyle explains.

Educating through science has always been Lyle’s calling. After earning a history degree from California University of Pennsylvania, he landed an internship at Acadia National Park in Maine, serving as an educator, tour guide, and park ranger. “I basically was there to inspire people to appreciate the environment and conservation, making connections with nature and falling in love with it.” Having despised biology and chemistry in school, mainly for the bland way it was presented, serving at Arcadia was his chance to fall in love, too. “It wasn’t until I found myself knee deep in a tide pool that I thought, ‘Wow, biology is super cool!’”

Which is why the curriculum he designs finds ways to connect science with things like pop culture. “For example, to show that superhero superpowers are just like animal adaptations,” he says. “It needs to stick in their minds. Otherwise, it’s just information overload.”

Museum teaching artist Katie Trupiano agrees. “I was never a science person,” she says. “If my parents had put me in a science camp, I would have dreaded it every day. Those are the kinds of kids who I’m trying to target.” With a background in the creative arts, a degree in musical theater performance from Point Park University, and a job as education and accessibility manager at City Theatre, it’s the element of play that serves as Trupiano’s “in,” using live-action gaming and creative thinking exercises to get the more than 1,000 kids attending 63 summer camps excited about science and natural history. Infusing art into the summer camp experience is just one more pathway to reach young people.

“If we’re talking about ponds, I’ll take them into the museum to look at Monet’s Water Lilies. I’ll ask them, ‘What time of day do you think this is?’ or ‘What objects do you see?’ and it’s amazing. They see things I don’t, and I’ve been up there a hundred times.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature