One hundred years ago this past July, not long after the last of the once-plentiful passenger pigeons vanished from the skies, a cornerstone wildlife protection law passed in the U.S., the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In addition to explicitly protecting more than 1,000 species, it has also provided a critical incentive for industries to take actions to reduce risks to birds. Today, as hundreds of bird conservation organizations worldwide celebrate the “Year of the Bird” as a way to mark the centennial, it is with the sobering and urgent knowledge that birds’ habitats are shrinking, and the legislation responsible for protecting them has been walked back by the federal government. A reinterpretation of the law now absolves companies that engage in foreseeable and preventable activities that kill birds—despite the knowledge that many of the deaths are easily avoidable and for decades industries have partnered with conservation groups to develop bird-safe solutions. The U.S. Department of the Interior argues that the law should only elicit penalties when individuals or companies are trying to kill migratory birds—a practice that will surely put many more birds at risk. Why does it matter? For one, healthy bird populations are essential to human well-being. Birds devour pests, keeping farmers in business. Birds are vital seed dispersers for plants that provide food and medicine, they’re a key indicator of imbalance in ecosystems, and so much more. We asked a few local bird lovers to weigh in on why birds matter. It’s no surprise no two answers are alike.

We’re interconnected

By Ashley Cecil, artist

Ashley Cecil, Kingfisher on Orange Wreath, 2016, watercolor, pen and ink, oil, and 22k gold on paper

Birds matter because their condition foreshadows what’s to come for our own species. We should feel the same level of concern for them as we do our own family members.

In an age when people often are far removed from nature, I find solace in closely studying birds by making art inspired by them. Masterfully capturing a bird’s likeness with a pen or paintbrush must be one of the purest forms of ornithological study. I’ve come to understand aspects of them by rendering their shape on canvas until it was intuitively clear that, for example, a hummingbird’s beak was built for nectar feeding.

This method of active learning makes art a valuable tool for understanding and appreciating the grandeur of nature. Birds, in particular, make excellent subjects—their stunning variation in color, pattern, and shape beg for careful inspection. Through this creative pursuit, my studio has become a sort of lab.

Beyond any one artist’s benefit, art is also an approachable means for the public to be curious about birds, appreciate their beauty, and understand their importance to our health. Not everyone absorbs information when read or spoken. For some of us, understanding comes from seeing

and feeling, and that’s what makes art a powerful conduit to knowledge.

Art has the ability to draw us closer to this creature that plays an important role in the well-being of our shared environment. And what we know intimately we are more inclined to protect. Summed up more eloquently by Oscar Wilde, “No better way is there to learn to love Nature than to understand Art. It dignifies every flower of the field. And, the boy who sees the thing of beauty which a bird on the wing becomes when transferred to wood or canvas will probably not throw the customary stone.”

Naturally selected for flight

By Chase D. Mendenhall, assistant curator of birds at Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Osprey Photo: David Y. Amamoto

Flight has evolved at least three times in animals with fleshy bodies built around a backbone—in pterosaurs, birds, and bats. Among each group, wings evolved from existing appendages, organs underwent natural selection to increase power, and novel strategies to decrease the mass of their bodies triumphed. Birds are the best vertebrate flyers because for more than 150 million years of natural selection their bodies have been shaped to fly—more than triple the time bats have been in the air.

Birds fly so well because they repurposed dinosaur anatomy to build bodies for flight. In fact, avian natural history provides clues to extinct dinosaur biology. For example, all birds breathe through a network of internal air sacs that span the length of their bodies and supply fresh oxygen to their unique, flight-ready lungs. It is thought that the air sacs of dinosaurs evolved to structurallysupport their bodies, some growing as large as a float in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

“Flight brought birds to every continent and ocean, and they would diversify into more than 10,000 species over millions of years. Song, radical coloration, nest building, and dancing have made birds powerful symbols for love and cooperation.”

Birds repurposed dinosaur scales into diverse “protofeathers” that would eventually serve as the raw materials for the evolution of bird feathers. Dinosaurs are thought to have used rudimentary feathers to keep warm, communicate, camouflage, and chase prey. Over generations, filaments continued to fraction and branch in diverse ways—eventually forming the microscopic hooks that zip the vane on a feather together to form a strong, flexible appendage for flight.

Flight brought birds to every continent and ocean, and they would diversify into more than 10,000 species over millions of years. Song, radical coloration, nest building, and dancing have made birds powerful symbols for love and cooperation. Incubating eggs in a nest and parenting warm-blooded chicks has generated a beautiful diversity of social reproductive behavior among birds. The diversity of bird parenting strategies range from dropping an egg into another’s nest (cowbirds), a single mother or single father raising a brood alone (manakins and tinamous), or parents splitting up tasks—as a pair (ostriches and 90 percent of all birds), a trio (oystercatchers), or a group (Acorn woodpeckers). Their diverse family arrangements make their sex lives and parenting strategies valuable case studies of cooperation—a trait many bird families share with human families.

They make us curious

By Michele Rice, Carnegie Museums member and mother of three explorers

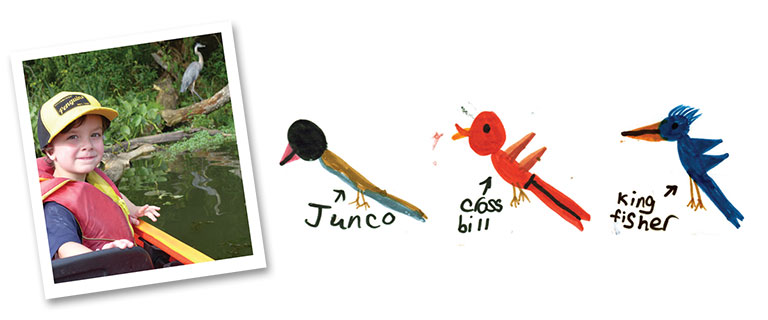

Illustrations by Nathan Rice

When my third child, Nathan, was a toddler, he was into birds—I mean, really into birds. We spent our time at the National Aviary, touring the bird exhibit at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and looking for birds everywhere we went. I couldn’t believe what we could see in our backyard or on a short drive to North Park. He made us a family of birders. My husband runs in North Park listening for kingfishers, we watch overhead as herons fly by, and we walk the dog listening for the towhee’s song “drink your tea.” We all have Nathan to thank for this hobby and the excitement that comes with each new discovery.

I interviewed Nathan, who is now 7, about why he likes birds: “I like them because they are colorful and fun to watch. My favorite birds are kingfishers and great blue herons—they do cool things. Herons go into the water and eat fish; kingfishers can fly up high then go diving into the water for fish.”

Birds keep our curiosity alive. There is nothing that gets my heart pumping more than a new discovery outside. On vacations we learn what new birds we can see and set out to find them. We were recently in Nevada and Nathan wanted to spot a roadrunner in the wild. As a family, we set out to find one. We were unsuccessful in that pursuit, but along the hike we spotted four bighorn sheep and spent three hours overlooking beautiful, blue Lake Mead. There is no app my kids can download for that.

In today’s world where habitat destruction is constant and kids are glued to their latest electronic devices, getting outside and engaged is crucial for our next generation to make a change and protect our environment. The more you know, the more likely you are to be a steward for the environment and all the things that call it home. So, get outside and learn something new today!

Expanding our sense of place

By Patrick McShea, Carnegie Museum of Natural History educator

Photo: Steven Kessel

Noticed birds enhance learning. Observing a cardinal pecking at its window reflection or a bald eagle soaring above a Pittsburgh neighborhood can motivate us to learn more about broader topics such as instinct or migration. At every noticed appearance, birds can widen our perspective, creating vantage points that vary with both observer and species observed.

Sometimes birds attract attention because they’ve already drawn the attention of other people. “What’s everyone looking at?” asked the North Shore trail runner as he slowed to a stop one cold February evening. He was dressed for exercise, but the dozen people obstructing his path were bundled in heavy boots and hooded parkas. We all had binoculars, and half of us peered through tripod-mounted spotting scopes at the ice-caked waters of the Ohio River.

“At every noticed appearance, birds can widen our perspective, creating vantage points that vary with both observer and species observed.”

Several hundred ring-billed gulls and herring gulls rested on the ice, and flying among them was a large pale bird. As the group’s least skilled gull identifier, I fielded the runner’s question while still listening to the discussion of those tracking the mystery bird.

In the literal shadow of Heinz Field, I attempted to explain the appeal of a spectacle far different than professional sports. “Pittsburgh’s rivers offer open water during the coldest weather,” I explained, “and the gulls gather here at dusk to spend the night.”

Before I could describe the two species represented in the flock, there came a loud celebratory confirmation of a third. “That’s a glaucous gull that just came in!” shouted a confident watcher behind one of the spotting scopes, setting me up perfectly to finish my answer. “The birds out there might be from all over the Great Lakes region, and it’s likely a few of the young herring gulls hatched just six miles up the Allegheny in nests on the piers of the Highland Park Bridge. The bird that just came in, the glaucous gull, is a big deal because that species mostly nests above the Arctic Circle.”

Someone with a spotting scope offered the runner a close-up look, ensuring that he could resume his circuit with an understanding that birds matter, even in fading February light, because their appearance can drastically expand our geographic sense of place.