For this Carnegie International, painting is migrating out of oil paint, off the canvas, into many other forms,” says curator Ingrid Schaffner.

She considers painting a “subplot” of the 57th edition of the exhibition, with the worlds of architecture, design, nature, decorative arts, and literature all providing content and context for today’s contemporary painters—even inspiring their choices in materials, colors, and format.

Among the painters creating new works for the show, which opens October 13, are Sarah Crowner, Ulrike Müller, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, each of whom explore the medium in bold and surprising ways, and from novel starting points.

As Crowner contemplated her work for the International, it was the world she discovered within Carnegie Museum of Art that started her thinking. After touring the Heinz Galleries this past May, she was inspired by the space itself. “It’s impressive,” Crowner says. “The ceilings are high and there’s a beautiful terrazzo floor. It has a grand, symmetrical feeling, and I knew I wanted to do something that paid attention to or honored the architecture.”

Sarah Crowner at work on a sewn canvas in her studio. Photo: Rosy Keyser

She looked to the skylights, which Müller suggested opening, to bring another, ever-changing dimension to her work. “I think it’s interesting the ways in which painting can respond to light and nature,” she says. “It then becomes something that’s living and malleable, not something that’s fixed.”

The Brooklyn-based artist is creating two new works—one made of terra-cotta blue-glazed tiles, the other a sewn canvas. Both are large, hang on the wall, and from Crowner’s perspective fall somewhere between painting and architecture.

“I always had this idea about walking on a painting or immersing yourself in a painting,” she says. “I started working with colorful tiles making floor installations. It occurred to me that tile is a form of hard-edged geometric painting. There’s a lot of gesture, imperfection, and inconsistency within the surface of each tile,” Crowner adds. “It relates so much to painting.”

Her stitched works reflect that same mindset. Their shapes and curves are cut out of different canvases, and their lines are the seams that bind the patterns together. Though installation-based, they’re informed by a painterly way of looking at and processing the visual world.

“Sarah’s work casts us as compositional elements or players within a more expanded field that she’s calling painting,” says Eric Crosby, Carnegie Museum of Art’s Richard Armstrong Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art. “It’s a liberating way of thinking about a medium that is so often defined by its limitations.”

An installation view of Crowner’s 2016 exhibition Plastic Memory at Simon Lee Gallery in London. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography, courtesy of the artist

Composed of adjoining panels, Crowner’s vibrant, 64-by-8-foot tile painting is described by International associate curator Liz Park as a “wash of blue” that will greet visitors at the top of the Scaife stairs, a main entrance for the exhibition. From there, the work will punch its way into Heinz Gallery A, prompting visitors to follow, as it flows from a pale blue to a darker blue along the way. Once inside Heinz Gallery A, museumgoers will also find Crowner’s wall-sized sewn canvas and Ulrike Müller’s baked enamel on steel and woven-rug paintings.

“Sarah’s work will very much catch the viewers as they come up the stairs and point them into the exhibition,” Müller says. “I was interested in creating moments of resistance in relation to that flow so that there is a tension—a closeness and a farness, a fastness and a slowness—a certain engagement from the very beginning of you entering the space.”

Müller’s choice of enamel and wool is no accident. “Painting is a medium associated with art-historical canons and certain notions of power,” she says. “I’m interested in decentering those ideas, and one way to do that is through material.”

Unexpected tension

Müller’s use of enamel evolved from her desire to develop the visual vocabulary of her drawings in a new medium. Working exclusively on paper simply didn’t cut it. “It was too quiet, too vulnerable,” says Müller, who was born in Austria and now lives and works in New York City. Ultimately, it was enamel’s sign-like quality that spoke to her.

She also likes its contradictions. “The enamel paintings look so geometrical and sharp-edged from a distance,” Müller says, “but then when you go closer there’s actually quite a bit of fuzziness in the lines because I use powdered glass.”

Her woven-wool-rug pieces offer a similar sensibility. And although she does have a background in textiles, Müller collaborates with rug makers in Mexico to transform her drawings into woven paintings, which she sometimes displays on gallery floors.

Ulrike Müller at the 2015 opening of Ulrike Müller: The old expressions are with us always and there are always others in Vienna, Austria. Photo: eSeL.at – Lorenz Seidler

For the International, she will introduce new wall hangings—six smaller enamel works and two new large-scale rugs. Both of the rugs will prominently feature a shoe.

“It’s a very specific image of a high-heeled woman’s shoe [and part of a lower leg] that is 8 foot tall and that can be read in a number of ways,” says Müller.

“The most obvious is along the lines of entering the space or stepping into the exhibition. But then it’s also a ridiculously large shoe, and it’s gendered and it’s sexy and it sits in an unexpected tension.

“I’ve had fun thinking about different ways in which this shoe could resonate in the contemporary moment,” she continues, “and in the context of the Carnegie—the museum and the International. It’s introducing a signifier that holds enough different kinds of potential meaning.”

But, says Müller—who is known for her use of a wide range of artistic mediums, including performance and publishing, to explore the relationship between abstraction and the human body—meaning is not inherent to the artwork. “It’s what happens when somebody is looking at, talking about, and interacting with the work.”

Ulrike Müller, Wraps, 2018, vitreous enamel on steel, Courtesy of the artist

Crosby is attracted to the importance of drawing in Müller’s pieces. “Regardless of her chosen medium, there is always something intimate and hand-drawn in the work,” he says. “She’s also an incredible colorist who’s exploring the different ways in which color can prompt an emotional reaction or evoke an historical reference.”

Over the past year, in preparation for the reinstallation of Carnegie Museum of Art’s contemporary galleries, which opened in July, Crosby has given much thought to the museum’s robust holdings in contemporary painting, a clear strength of the museum’s permanent collection thanks in large part to acquisitions from past Internationals. Some of the heavyweights whose works were collected out of the show just in the past two decades include Laura Owens, Christopher Ofili, Peter Doig, and most recently Nicole Eisenman, the winner of the 2013 Carnegie Prize. An entire gallery of the museum’s contemporary reinstallation, which Crosby titled Crossroads: Carnegie Museum of Art’s Collection, 1945 to Now is devoted to the “challenges and pitfalls” of contemporary painting.

“What Ingrid has done with her choice of painters for this International,” says Crosby, “is invite all of us to imagine what else a painting can be.”

Every picture tells a story

“Ahistoric” is the term Lynette Yiadom-Boakye uses to capture the enigmatic essence of her paintings. Unveiling a new series of portraits for the International, her signature style is unambivalent: large oil-on-linen canvases, hung low on the wall, and featuring black figures.

At first glance, Yiadom-Boakye’s work seems to recall the classic style of portraitists who have come before her. And so, one might assume that her subjects sit for days as she studies their faces, gestures—their very souls.

But the people who populate Yiadom-Boakye’s world don’t exist in ours. They are manifestations of the artist’s imagination. “Everything’s a composite,” this daughter of Ghanaian parents who moved to London 50-some years ago told Interview Magazine in 2017. “I work from sources. I make scrapbooks, I make drawings, and collect things that I might use later, so they are all very literal compositions in the way that I pull things together. A lot of that decision-making happens on the painting itself. In each case, it’s a negotiation of how I want each figure to fill the space.”

An installation view of the 2017 exhibition Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Under-Song For A Cipher at the New Museum in New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio

There are also negotiations going on between the written word and the brush stroke. “I’m endlessly fascinated by Lynette’s work and her cast of characters,” Crosby says. “The work is rooted in writing, and the entities she conceives then take physical shape in paint.”

For Yiadom-Boakye, who lives in London, the two pursuits are inextricably linked. “The same thread of logic runs through my writing and painting. It’s something to do with having a particular way of thinking creatively. The things I can’t paint, I write, and the things I can’t write, I paint.”

Artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye with work from her Versus After Dark exhibition, Serpentine Galleries. Photo: The PinchukArtCentre © 2013. Photographed by Sergey Illin

Although she admits that her writing projects are still very much works in progress, each of her paintings usually begins and ends in one exhaustive eight-hour session. Despite that sense of immediacy, they purposefully betray no sense of time or place.

“The timelessness is completely important,” she said in Interview. “It’s partly about removing things that would become in some way nostalgic. There aren’t really any markers of time, like furniture or a particular style of shoe that denote a particular period or place. I think that’s why I like the outdoors, because it removes a sense of time and I want the painting to feel timeless, because it increases that sense of omnipotence.”

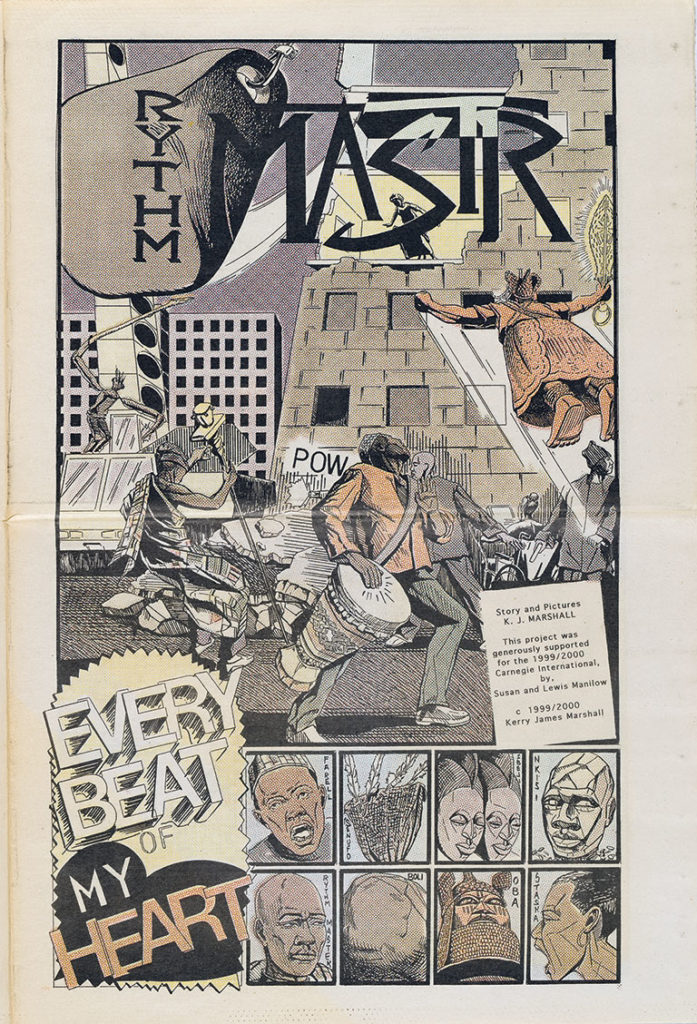

Kerry James Marshall, Rythm Mastr, 1999–present, © Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Kerry James Marshall is returning to his epic narrative featuring black superheroes two decades after the comic series debuted at the 1999 Carnegie International.

That sense of power and influence can be exhilarating, and in at least some small way that’s what the International is all about. Dating back to its debut in 1896, after which the museum acquired paintings by Winslow Homer and James A. McNeill Whistler, the show has always informed the museum’s permanent collection.

This year’s International will be infused with new ways of considering painting today as prompted by the work of Crowner, Müller, and Yiadom-Boakye. Also noteworthy are the print-like paintings of words by Mel Bochner (at right), an installation of strangely romantic paintings and photographs by Karen Kilimnik, and a return to an epic narrative by Kerry James Marshall, who is revisiting his Rythm Mastr comic series featuring black superheroes two decades after it debuted at the 1999 Carnegie International.

“Painters are always reaching back—reaching back and pulling things forward,” says Crosby. “Our collection so eloquently speaks to how artists have done this over the years.”

Come October, perhaps the past will be present once again as old ideas are revisited among the new.

“Ingrid [Schaffner] is making a very serious effort to evaluate an old convention, the tradition of the exhibition format, to see how much weight it can carry in this moment,” Müller says. “For me, it’s an opportunity to think about how my work fits in this situation. It was also a challenge in terms of scale. The rugs are the biggest pieces I’ve ever made. It wasn’t necessarily my primary ambition to go large, but I liked the challenge.”

The Carnegie International, 57th Edition, 2018, presented by Bank of America, is made possible with major support from the Carnegie International Endowment, The Fine Foundation, and the Keystone Members of the 2018 Carnegie International. Additional support is provided by the Friends of the 2018 Carnegie International, the Jill and Peter Kraus Endowment for Contemporary Art, the National Endowment for the Arts, the EQT Foundation, The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art, and the Louisa S. Rosenthal Family Fund.