Under a hazy blue sky on a hot and sticky June morning, Raven Chacon and Cristóbal Martínez circle the scrap heaps scattered along the grounds of the Carrie Furnaces in Rankin, just east of Pittsburgh. Over the next several hours, bare-handed and determined, the artists dig in, salvaging material to use in a monumental site-specific installation in Carnegie Museum of Art’s Hall of Sculpture.

Accumulating in their “take pile” are pipes of all sizes, I-beams, tangled cables, hefty stacks of rectangular plates, what appears to be a locker, and a 9-foot ladder—all rusted steel vestiges of the now idle, hulking blast furnaces. Much of their harvest, some 11 tons in all, are remnants of the top of a towering hot-stove stack that, for safety reasons, was painstakingly disassembled last summer.

Chacon and Martínez, with fellow artist and instigator Kade Twist, form the interdisciplinary artist collective Postcommodity. They live and work in New Mexico and California andcome from indigenous backgrounds (Navajo, Mestizo, and Cherokee, respectively) that inform their practice. The day’s foraging for mostly 100-year-old steel is part of the trio’s fourth trip to Pittsburgh and second visit to the former U.S. Steel complex to prepare for the Carnegie International.

Over the past year, as they’ve developed the work of art that now blankets 2,000 square feet of the Hall of Sculpture’s brilliant white marble floor, they’ve merged—and complicated—the histories of industry and jazz in Pittsburgh.

Kade Twist of Postcommodity in the early stages of building the collective’s installation on the ground floor of Carnegie Museum of Art’s Hall of Sculpture. Photo: Bryan Conley

“An assumption of ours is that when people think about the steel industry, they probably think about blood, sweat, and tears—and football,” Martínez says. “But maybe not so much about the role of African Americans in the context of that history, or how the role of industry has been a factor in the emergence and the rise of jazz in America.”

On a guided walking tour of Pittsburgh’s Hill District by ethnomusicologist Colter Harper and in the images of the late Pittsburgh Courier photojournalist Teenie Harris, the three men discovered the ghost of the African American city-within-a-city that from the 1930s to the 1950s was a mecca of black culture and business known as “the crossroads of the world.”

Through the lens of Harris’ camera, Postcommodity learned of the neighborhood’s essential place in jazz history—launching the careers of the likes of First Lady of Jazz Mary Lou Williams, Billy Eckstine, and Erroll Garner, and, in its heyday, serving as home to more than 30 jazz clubs, regular stops for national artists. But the trio’s conversations with community members would quickly move on to talk of racial discrimination in the mills, the hard-fought unionization of the city’s black labor, and the city’s urban renewal of the 1950s that displaced more than 8,000 residents and 400 businesses, forever changing the neighborhood.

“Through that experience we began to imagine the connections between what black steelworkers were experiencing at the workplace in relationship to maybe what it might have felt like after a hard day’s work,” says Martínez. “You know, going out to the club on weekends and listening to jazz, and how those stories, those feelings, those experiences influenced the music. Part of it was listening to those stories, letting them sink into our bones, and providing feedback through the artistic process.”

Embedded in Postcommodity’s installation titled From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home are symbols that include an abstracted North Star and the confluence of Pittsburgh’s rivers—a path toward freedom and “perceived social and cultural mobility,” says Twist. It’s the story of the Underground Railroad and a people swept north during the Great Migration for the opportunity to make iron, steel, and aluminum. From the years of World War I through the late 1960s, 6 million African Americans moved from the South to the North and West, with more than 100,000 African Americans ending up in Pittsburgh. The movement was momentous not only for its scale, but because it was organic; it was not organized.

“An assumption of ours is that when people think about the steel industry, they probably think about blood, sweat, and tears—and football. But maybe not so much about the role of African Americans in the context of that history, or how the role of industry has been a factor in the emergence and the rise of jazz in America.” — Cristóbal Martínez

“They came for a better life, and now we are experiencing another wave of northward migration. And so, do we position those historical narratives as contemporary metaphors for new immigrant experiences?” Martínez lets the question hang in the air. “This is a way of remembering. By remembering we can see history repeating itself. In negative ways, in positive ways, and everything in between.”

Within the 57th edition of the Carnegie International, opening on October 13, a number of artists, like Postcommodity, will ask visitors to wrestle with history, and with what curator Ingrid Schaffner calls “shifting terrain”—issues of borders and boundaries, nationhood, and a world and its people in transition.

The architecture of displacement

For Saba Innab, a Palestinian architect and urban researcher, questioning the meaning of architectural and urban planning in a state of occupation and constant conflict is a recurring theme. Through painting, mapping, sculpture, and design, Innab, who was born in Kuwait and lives between Amman and Beirut, says she’s constantly working through notions of building and dwelling in “the temporary that is mutating into a permanent state,” referencing the Palestinian refuge and exile as a point of departure.

For the International, the artist is creating a site-specific work for the Museum of Art’s beloved Hall of Architecture. Titled What is Unseen Cannot Be Broken, the work is an abstraction triggered by an image of a partially exposed tunnel in the Gaza Strip, a tiny coastal wedge that is home to nearly 2 million Palestinians. The tunnel had been excavated by the Israeli army. “Seeing becomes destroying,” Innab says. “To think about this image, invisibility is what keeps the tunnel.”

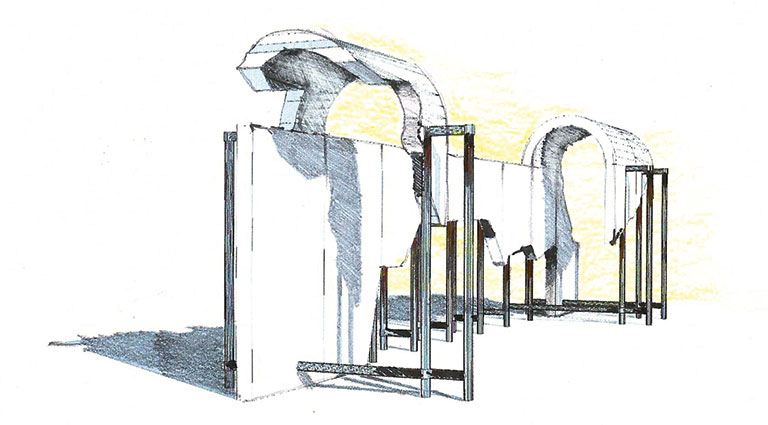

Saba Innab, Study, 2018, Courtesy of Saba Innab

An early sketch by Saba Innab of her installation for the Carnegie International.

Gaza citizens have been digging and using tunnels for years. Because of the Israeli blockade of Gaza, introduced when Hamas won elections in 2006, the underground passageways have been an economic lifeline for Gaza citizens in need of basic consumer goods like food, clothing, and gasoline.

In recent years, Hamas has boasted of a border tunnel-building frenzy. Referring to them as “terror tunnels,” the Israeli military says the new vast tunnel network is complex and advanced and designed to carry out attacks on Israeli civilians and soldiers alike. Israel reports destroying a number of them.

“Simply, Gaza is under siege, and the tunnel is a way of survival,” Innab says. “To expose the tunnel—whether by exposing it physically or freezing it in a museum of dominantly Western history—the movement becomes the impossibility of movement.

“Things are better recognized by their contraries; we recognize movement when we are still, and a gate is a gate because it closes. Everything can be the thing and its opposite, depending on where we stand. The tunnel is a structure, or a method of survival. When excavated, it becomes the sign of the colonizer—so the oxymoron is not only represented in the possibility/ impossibility of movement.”

Saba Innab, Time is Measured by Distance, Commissioned by Marrakech Biennale 6, 2016, Courtesy of Saba Innab

Innab’s contribution to the 2016 Marrakech Biennial, Time is Measured by Distance, emulates the negative space of the Strait of Gibraltar, the narrow passage that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa. Photo: Photo: Diego Jiménez

The International marks only the second time the artist will exhibit in the United States. Innab says that while specific audiences don’t impact the way she thinks about a project, sites are always implicated in her work.

Asked if she considers her project to be in dialogue with the rare collection of 140 architectural casts of the Greco-Roman world housed in the Hall of Architecture, she says, “I think it’s a contrast more than a dialogue; the collection assumes a specific mode of authority of a major history line, with clear writers of history. What I’m interested in is not only to challenge this authority, but it is also an invitation to imagine the source of the excavated body; to imagine what is normally marginalized, terrorized—which is also a form of resistance and survival.”

Life along an invisible line

While Postcommodity was reconstructing Pittsburgh’s past, New York-based artist Zoe Leonard was out exploring with her camera the once-mighty Rio Grande as it flows downstream from Juárez, Mexico, on one side, and El Paso, Texas, on the other. She’s focusing on both sides of an 1,100-mile stretch, says Leonard, “where a natural feature is used to perform a political task.”

Leonard’s three-decade-long career producing photography and sculpture that tussles with themes like migration, the urban landscape, and gender and sexuality is being celebrated in a major retrospective slated to open in November at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, after debuting at the Whitney Museum of American Art this past spring.

Zoe Leonard, Image from Rio (working title), 2016-2018. Gelatin silver prints. © Zoe Leonard, Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galerie

For this latest project, she photographed the desert and the mountains, the cities and the villages, the farms, factories, fences, armed barricades, and the pastoral open country that coexist with and often are made possible by the Rio Grande. In some areas, it’s now just a trickle due to historic drought and irrigation demands on both sides of the border.

“ I am looking closely at the river in order to observe the multiple and complex pressures that bear down on this thin line of moving water; this work is a way of thinking about a larger social and political landscape.”

– Zoe Leonard

For the International, Leonard will show Prologue, the first part of ongoing work titled El Rio/The River. She has written: “Historically, the Rio Grande has figured large in the public imagination, as a symbol and icon of the American West. Currently it is at the center of contemporary political debates regarding borders, immigration, national security, labor, economy, culture, climate change, energy, resources, drug trade, wildlife, and water rights.

“I am looking closely at the river in order to observe the multiple and complex pressures that bear down on this thin line of moving water; this work is a way of thinking about a larger social and political landscape.”

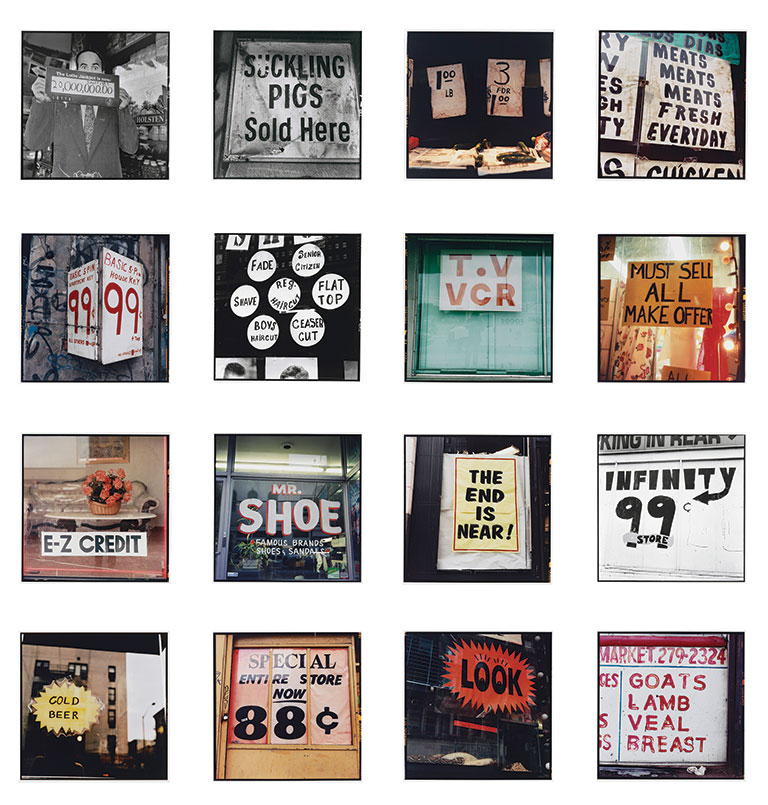

Zoe Leonard, Analogue (detail), 1998–2009, 412 C-prints and gelatin silver prints, 28 x 28 cm/11 x 11 inches (each) © Zoe Leonard, Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne Photo: Scala/Art Resource, NY

Made over decades, Analogue (above) is a landmark project by Zoe Leonard that in 412 photographs connects the vanishing mom-and-pop shops from her Lower East Side neighborhood to the emergence of a global rug trade.

The U.S.-Mexico border is also the site of a past work by Postcommodity. Repellent Fence crossed the border with a line of “scare-eye” balloons highlighting both the absurdity and humanity of border politics. It seems fitting, then, that Leonard’s photographs of the Rio Grande on the second-floor balcony of the Hall of Sculpture will hang above the collective’s work on the hall’s ground floor.

An installation detail from Postcommodity’s 2015 Repellent Fence. Photo by Michael Lundgren, courtesy of Postcommodity

The act of remembering

Over four full days in late July, Cristóbal Martínez and Kade Twist—armed with brooms, a rake, and orange contractor buckets full of crushed glass and coal—painstakingly installed From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home. It was a monumental effort made possible with the added muscle of three museum preparators and two installation assistants.

“We’re riffing on the sand painting, reimagining its ceremony,” says Twist. “The Navajo were not concerned about the Rust Belt. But the tribes suffered lots of casualties in construction.” In traditional Navajo sand paintings, finely ground charcoal, cornmeal, and turquoise are among the materials used to form a storyline of harvests and healing. In addition to chunks of rusted steel, Postcommodity added to its palette 7 tons of recycled white crushed glass from Dlubak Glass in Natrona Heights and 3 tons of nut and stove coal from Kiefer Coal & Supply in Bethel Park, references to important themes in their art and music practices: cultural self-determination in the face of the destruction of native lands through the extraction of fossil fuels.

While the focus is on Pittsburgh’s history, the sacrifices made by marginalized laborers is personal for Twist and Martínez, whose fathers were a steamfitter and a metalworker, respectively.

“The entire city of Pittsburgh made sacrifices for this country. The labor is a shared sacrifice,” says Twist. “The entry point [for the painting] is black history, but it’s relevant to all Rust Belt towns. Eighty years of suffering—that’s a lot of cancer, death, a lot of families dealing with emotional and physical pain.”

Martínez looks out over the finished artwork: “There are lots of secrets in there. There are lots of ideas. We’ve been making art together for a long-time, and things emerge and recede. We thought about coded messages, symbols, the confluence of ideas, connected knowledge, drawing a through-line across complexity.

“This is a pictogram,” he says. “It ties to images and ideas we grew up with. There’s a river, a snake, of course lots of Western influences, lots of influences from Africa, from our own peoples.”

But the painting’s story, says Raven Chacon, is for the people of Pittsburgh to tell.

The group is partnering with James and Pamela Johnson, the founders of the Afro American Music Institute in Homewood, to identify a rotating group of intergenerational jazz musicians to interpret the painting by performing it. In September, Chacon, who is a composer, will work with the musicians to develop their own readings of the work that doubles as a graphic score.

“As a musician, you analyze the various regions of the work and you take from it; this part is telling me to play so many nodes, or I have to have so much texture to my playing,” he explains. “There is no wrong way to play it, but there are guidelines to help you navigate it.”

From the Hall of Sculpture balcony, at 1 p.m. on Thursdays through Sundays during the run of the exhibition, a single musician will emerge, “telling us their own version of the story,” says Chacon.

As the first note is played, the rear doors on the lower level of the Hall of Sculpture—which have been closed to the public for decades—will open, the music transmitting the ideas throughout the building and across disciplines.

“It will provide audiences with an opportunity to construct a kind of emotional experience with Pittsburgh’s history,” says Twist. “It’s a spiritual communication to open yourself, to open the institution up, to let people listen together and feel connected.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up