“I saw Teenie’s photographs for the first time when I was 18,” says artist and cinematographer Bradford Young. American photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris’ images of black urban life in Pittsburgh are a point of departure for Young’s three-channel video installation, REkOGNIZE (2017), the latest artwork commissioned for LIGHTIME, a project of the Hillman Photography Initiative at Carnegie Museum of Art. “The things that really spoke to me about Teenie’s work was that beautiful balance between deep intention and engagement with the community at the most fundamental level.” The gravity that Harris brought to every frame of film, that interplay between the ordinary and the sublime, is what drew the 40-year-old artist to the work of the late photographer.

In the 1930s, Harris purchased his first camera and set his sights on imaging black Pittsburgh. Working his beat for the Pittsburgh Courier, a local African American newspaper with a wide readership, often led him to the Hill District, the historically black community that sits above the city’s downtown. He roved the heart of the Hill’s streets, seemingly snapping a picture of everything. His archive of some 80,000 photographs, which is housed at the Museum of Art, offers the record of a people who were swept north during the Great Migration to manufacture steel and the later decadence of postindustrial black urban life.

In black and white, Harris chronicled quotidian scenes of blackness. There are images of Pittsburgh Negro League legend Josh Gibson working the field in his catcher’s uniform, the great American playwright and the Hill’s native son August Wilson sitting in a public amphitheater at Point State Park, and the trailblazing pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams making jazz history. One image from 1942 of a wedding party posed in a front yard on Chalfont Street captures the Steel City’s black middle- class glamour, recalling James VanDerZee’s pictures of Harlem. In others, black men, women, and children are grasped in rapture, dancing, crying, trick-or-treating, politicking, and mourning. For nearly five decades, Harris’ lens saw it all, imaging the fullness of one black community’s rhythm and blues.

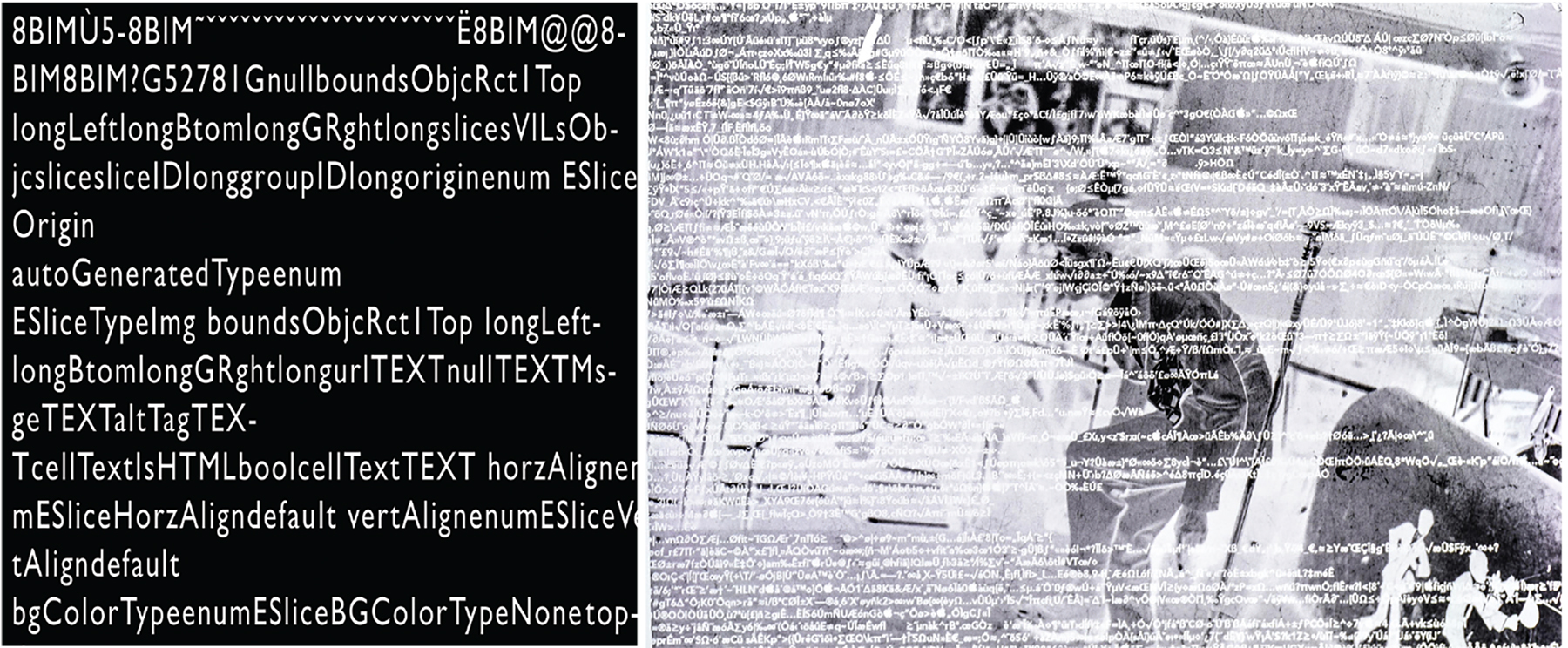

To create REkOGNIZE, Young took 10 of Harris’ pictures and digitized them as a way to “release the metadata of the images.” The artist took, for instance, Harris’ image of a nighttime Pittsburgh landscape and scanned it. Before the scanning process rendered the late 1930s/early 1940s photograph as a digital file it produces the image’s underlying binary code of at least 140 pages of numbers, hashtags, and symbols known as “metadata code.” Young is interested in seeing what the binary information says about the images’ tonal value, light, and space. Harris’ art, like Young’s cinematography in films like Selma (2014) and conscious rapper Common’s recent music video Black America Again (2016), uses what Young has called “available light” to physically and conceptually explore the shadow of a body or space. “What I’m trying to do is dig into his practice at the very fundamental level,” Young says. “I think he knew how to bend light and shadow in a way that meant the most for black people, for black bodies, for black space.”

Installation view of REkOGNIZE (2017) at Carnegie Museum of Art.

In REkOGNIZE, Harris’ photography is the catalyst for both image and sound. On one channel of the installation, parts of the unearthed code create a representation of the numeric layers beneath the images that establish their essence. As Harris’ photographs flash on screen, code scrolls across the faces of men, women, and children from the Hill District, their expressions veiled by alphanumeric masks. Behind their bodies numbers drop in rapid descent, conjuring a sense of disintegration. And within their bodies the code consumes them, cutting a silhouette both familiar and foreign. “I’m trying to crack the code,” Young explains. On the installation’s other two channels, the cinematographer’s black-and-white footage of the Hill and Pittsburgh’s well-traveled tunnels act as an anchor to the present.

The metadata collected from Harris’ images also informs the installation’s slow-moving, melancholic score. “Even before Bradford sent images,” explains Jason Moran, who composed the installation’s sound, “we started talking about what is space in a photograph?” Like a true jazz man, Moran improvised from a theme: darkness. Like the installation’s filmic images, its score explores darkness as a photographic technique, the color of a community, and a state of mind. Using the quantities involved with the depth of brightness of the images that inspired REkOGNIZE, Moran produced a score that corresponds with the bottom 10 keys of the piano. “I took sections of the [images’] data that renders these long series of numbers, and then literally mapped them with the corresponding piano notes.” If the digitizing computed, for instance, 0013, and “0” corresponded with note c, Moran would read “00” in the sequence and hit the c note twice. For the “1” in the series, Moran would move a half step on the piano.

A portion of metadata and how it scrolls across images in REkOGNIZE.

“What I’m trying to do is dig into his practice at the very fundamental level. I think he knew how to bend light and shadow in a way that meant the most for black people, for black bodies, for black space.”

– Bradford Young

“Composers rarely put that much darkness in combination with one another,” Moran says. “If I take the bottom 10 notes and play them all together for eight minutes, that makes a world rarely heard. That’s where we started.” Moran then got inventive, adding trap beats, today’s expression of black pain and pleasure. The conceptual composition also accounts for the tension, color, and sounds that pierce Harris’ images. There are moments of pure sonic speculation, which is to say jazz, where Moran imagines abstractly the sound of the flashbulb from Harris’ camera or the pow of the gunshot that killed Raymond Jones in Crestas Terrace back in 1949. In every one of Moran’s notes lives the bebop of Mary Lou Williams and the swing of Erroll Garner, two of Pittsburgh’s great black jazz pianists. The score is a kind of jazz that works in tandem with Young’s moving images to convey a history of the darkness beneath black space.

A History of Erasure, Marginalization

On visits to the Hill, Young sat at the tables of community elders like lifelong Pittsburgh political activist Sala Udin. Udin told Young of life at home in the community. They talked in personal terms about the area: What it meant. What it means. Where it is now. Where it’s going. The 74 year old, who is a candidate for the Pittsburgh school board, was born in the Hill in 1943 to parents recruited north from plantations in Mississippi and Georgia to labor in the city’s steel mills. The history of the black community “throughout the country is like a paper cutout,” Udin says. “The face of it may change, but the actual dynamics were all identical.”

For the former city council member, one major city-led demolition largely tells the contemporary story of the Hill. The city, according to Udin, using funds partly drawn from the implementation of the postwar United States Housing Act of 1937, developed a residential and cultural plan to revitalize the Hill, which like most urban communities in America by the 1950s had fallen into disrepair. “In Pittsburgh, the federal policy and state policy added a layer of racial residential discrimination, or segregation,” Udin says, “which put white families in federally subsidized homeownership tracks and black families in public housing.” The city demolished 95 acres of homes in the lower Hill District with the promise to replace them. “They relocated 8,000 families and organizations out of the lower Hill District and drove a highway to the suburbs right through the heart of the black community.” In 1962, when the promises of redevelopment didn’t bear any fruit, community activists put up a billboard declaring, “NOT ANOTHER INCH.” The protest stopped the city’s plan to build on the land and from destroying anything east of the community’s line in the sand. Fifty years later, the land remains empty.

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Crestas Terrace police officer D. A. Cook and Dorothy Anderson at crime scene of murder of Raymond Jones, Crestas Terrace, 1949, Carnegie Museum of Art, Heinz Family Fund

“What I tried to do is put my feet in places where I actually saw beauty and trauma. Where the space could actually speak on its own.”

– Bradford Young

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Wedding party posed in front yard on Chalfont Street, 1942, Carnegie Museum of Art, Heinz Family Fund

Udin’s home was demolished. He moved with his family into the Bedford Dwellings housing projects. The house of his friend and Holy Trinity classmate, the future playwright August Wilson—who would later ask Udin to star as Becker in Jitney, the first play in his century cycle set in the lower Hill District—was saved. “Teenie captures all of that in his photography,” says Udin, who left the Hill when he was 17 to become a Freedom Rider. “He captures the period of high cultural development that occurred with all of the baseball teams and the jazz and economic development,” Udin says. “All of that was captured through Teenie’s camera lens, and he captured the demolition.” In a photograph from 1969, which was turned into code for REkOGNIZE, Harris captured Udin at a press conference along with other local leaders espousing the unity of Black Power.

“The effect of the demolition and displacement is not as well captured,” Udin says. “Those images are more subtle.” REkOGNIZE is one way of documenting what came after. As the black-and-white code flashes on the screen, with Harris’ photographs of housing projects, wedding parties, crime scenes, and night clubs interspersed with their own digital DNA, the tone of the installation shifts from meditative to chaotic to violent before receding again to calm. It is both mesmerizing and jarring to witness—the collision of past with present. “What I tried to do is put my feet in places where I actually saw beauty and trauma,” Young says. “Where the space could actually speak on its own.”

A Witness to Light and Shadow

Young always had aspirations of becoming an image maker. He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1977 and raised mostly in the black middle-class section of the West End. He spent a lot of time with his mother’s parents, Woodford and Harriet Porter, who owned and operated A.D. Porter & Sons Funeral Home and kept black photography books. He remembers poring over Gordon Parks and Roy DeCarava’s images of the civil rights era and the vernacular images of the local black photographer Nat Brown, who, like Harris, shot the pictures of black weddings and funerals that ended up in family photo albums as a personal record of time.

“Photography always interested me,” Young says. “Like my sisters and my mom were always reading books to sort of transport them through time and space.” But initially books didn’t work for Young; photographs did. He would listen to his grandfather tell stories of going to Africa in the 1950s—or about what it meant to be a black man during the civil rights and Black Power movements—and a 10-year-old Young felt a connection between Woodford Porter’s stories and the photographs he saw. “I felt like the people in those coffee table books were my relatives,” he says, laughing. “That’s how photographs really always moved me.”

By age 12, Young was working in the family business. He would help his grandmother set up the chairs for funeral services, light the caskets, switch out the carpeting, and hang art in the parlor. He became fascinated by the way that within four walls “there was always a fine crossroads between love and loss, light and dark, and organized chaos.” It didn’t seem to really sit with me when I was 12 but by the time I turned 18 I realized, ‘Oh wow, those things really affected how I see the world and how I bear witness to light and shadow.’”

Young’s interest in light and shadow led him to Howard University in 1995. On the Hilltop, he studied film under the direction of legendary black filmmaker and professor Haile Gerima. Gerima helped shape the photographic sensibility of Young and a generation of black cinematographers such as Arthur Jafa, Malik Sayeed, and Ernest Dickerson. Gerima’s Ashes and Embers (1982), a tale about a disaffected black Vietnam War veteran, transformed Young’s ideas about image making. It showed him that there’s a “structural photographic” that creates a reality that plays with time and space and the construction of the moving image.

“In terms of its language and grammar, black cinema has to reflect us,” Young says. “And when it reflects us, it will not be the typical structure. It will have a very awkward structural reality as it relates to white supremacist storytelling structure.” Photographically, Young says, Roy DeCarava, Harris Savides, and Teenie Harris used their own relevant cultural language grammar as a way to express blackness through light and shadow.

Bradford Young behind the camera.

REkOGNIZE maps on one community the Academy Award-nominated cinematographer’s technical and cultural exploration of light and shadow. For nearly 15 minutes, the black and white film installation traces the history and long postindustrial decline of black urban communities in America. The project could have easily been shot in today’s Harlem, Bronzeville, Watts, or the West End, all spaces that burgeoned during the 20th century black exodus that collected black southerners from sharecropping schemes to labor in the cities and factories ultimately altered by redlining, Black Power, crack, and gentrification. Young’s camera moves slowly across the Hill, lingering on an empty basketball court at night, pitched tunnels, matted distant buildings, silhouettes of trees, bright street lamps, and flickers of white light under the cover of a shifting gray sky. It’s a dystopian journey of black space. At one point in the film, Young’s camera sweeps over what seems like a dark burden landscape hovering in a way that marks a moment of convergence between the stillness of Harris’ photography and Young’s film.

REkOGNIZE recalls the ways that Young, as cinematographer for Mother George (2013) and Selma (2014), routinely shot what’s referred to as an “empty plate”—a scene of the set without people present. The complications and contradictions of human existence are not seen but felt. Young’s 2012 collaboration with the artist Leslie Hewitt called Untitled (Structures), informed by a collection of civil rights era photographs, also seemed to have influenced REkOGNIZE. The two-channel video installation comprised a series of silent vignettes filmed at civil rights movement sites in Chicago, Memphis, and Arkansas, and unpacked the historical significance of black space. “Something that I learned working with Leslie Hewitt is to unpack space first,” Young explains. “Once we had a better relationship with space, then we felt we could add the next layer of mind and body to the frame. This is part of the reason why the installation is called REkOGNIZE.”

In wanting “the space to speak on its own,” Young doesn’t employ the black body to take up space in his frames of the Hill, although we know as the builders of the community they are central to its narrative. It’s as if Young is saying to the audience, like a late ‘90s rapper: y’all betta recognize where you are; recognize that I’ve got some shit to say; recognize blackness in total darkness. “In the absence of the space that is not there, there’s the space we make under duress,” writes the poet and theorist Fred Moten of black folks in his Blue Black exhibition catalogue essay, “Black and blue in white. In and and in space. Church and cell in absence.” Black people in the Hill and across America stretched out, found solace in circumstance, got inventive about surviving, turning blues into jazz. “How many times have you walked past this house with this tree just sitting nestled against it the way it is, and actually stopped and said, ‘Oh, that’s wonderful?’” Young asks, rhetorically. “I did a lot of that in the Hill District. ‘Oh, this is wonderful. This is beautiful. This reminds me of home.’”

This article originally appeared on Storyboard, Carnegie Museum of Art’s digital journal. Antwaun Sargent is a writer based in New York City. He has written for the New Yorker, The Nation, The New York Times, and Vice.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up