You May Also Like

Reimagining Landscapes Opening up the World for Others Progress in the Pop DistrictIn Kim Gordon’s memoir, Girl in a Band, the Sonic Youth co-founder and bassist mentions why the quartet wound up titling their Bad Moon Rising album after a Creedence Clearwater Revival song.

“That’s just the way we did things,” she wrote, “borrowing something from a pop culture landscape and giving it a different meaning.”

It reads like a tossed-off comment, as casual as the appropriation itself. But Gordon’s acknowledgement not only captures the essence of both pop art and Andy Warhol’s career, it expresses how deeply the influence of both permeated the entire art world and pop culture in general.

Examples of appropriation can be found in every aspect of Sonic Youth’s boundary-breaking work, from song titles such as “Sympathy for the Strawberry” and “Expressway to Yr Skull” to album art, videos, and even the band’s Ciccone Youth side project, for which they borrowed the pop star Madonna’s last name.

It’s a major element of Gordon’s visual art, too, as revealed in Kim Gordon: Lo-Fi Glamour, on view at The Andy Warhol Museum through September 1. Marking the artist’s first solo museum exhibition in North America, Lo-Fi Glamour includes paintings, ceramic sculpture, a new series of figure drawings, and a commissioned score for Warhol’s 1963–64 silent film, Kiss. The show takes its title from a quote in Gordon’s 2013 memoir: “I had always loved Andy Warhol, the Strip-like aesthetic that showed up in his movies and in the spray-painted factory in New York—the use of tacky, impure elements like metallic material and glitter, the lo-fi glamour of it all.”

Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art and co-curator of Lo-Fi Glamour, says the exhibition is more than a survey of Gordon’s work. It’s meant to connect the dots between the multidisciplinary artist and her influences.

“For Kim, Warhol has served as a standard for what it is to push boundaries with art practice,” says Beck, noting that the exhibition catalyzed new work that is on display for the first time—a series of nude figure drawings Gordon says were partly inspired by visiting The Warhol.

“I had always loved Andy Warhol, the Strip-like aesthetic that showed up in his movies and in the spray-painted factory in New York—the use of tacky, impure elements like metallic material and glitter, the lo-fi glamour of it all.”

– Kim Gordon

The idea for the exhibition grew from conversations Gordon had with Ben Harrison, The Warhol’s curator of performing arts and special projects and co-curator of Lo-Fi Glamour. The pair were introduced by Gordon’s friend, indie rocker Eleanor Friedberger, who was among the artists Harrison commissioned to create scores for The Warhol’s 2014 project, Exposed: Songs for UnseenWarhol Films.

Initially, the two talked about what Gordon had been doing recently musically and her interest in Warhol films, says Harrison. “But we quickly started to talk about what else she was doing in a very interdisciplinary fashion, and a returning back to her roots in visual art.”

Kim Gordon, Secret Abuse, 2009; Airbnb Hollywood, 2019; #Youdon’townme, 2017, Courtesy of the artist and 303 Gallery, New York

What developed, says Beck, is “a look at Kim as an artist who has been creating and developing her artistic practice for 30 years. The success of the exhibition is that we feature existing works, Noise Name paintings for instance, and also, through conversations about Warhol, we encouraged Kim to make new work. Seeing the collection and talking about a more intimate side of Warhol, which is one of my motivations with the collection, led to the new series of female figure drawings. It’s been exciting to see this inspiration of her site visit in her new work.”

#Faux

To Gordon’s surprise, she didn’t have any trouble digging out the pair of white, lace-up canvas boots she’s hung on to since Warhol autographed one during a mid-’70s book-signing appearance at a gallery in Venice, California.

“I just put my leg up there for him to sign,” says Gordon, now 66, who was an art student living in the boho beach community at the time. She chose the vintage boots instead of the Campbell’s Soup cans others presented because “they reminded me a little bit of early Warhol, of his shoe drawings,” Gordon recalls. He also initialed them—an extra-special touch, someone in his entourage told her.

There’s slight irony in the fact that the brief interaction—the only one the two ever had—didn’t occur in New York, where both felt so at home after leaving the cities where they grew up (Los Angeles and Pittsburgh), and where the degrees of separation between them were so few.

Though Gordon arrived in New York City in 1980, seven years before Warhol passed away, she would manage only to spot him there one day crossing West Broadway. Not even her connection to influential art dealer Larry Gagosian—who shows up in Lo-Fi Glamour in her Noise Name series—would put her in Warhol’s proximity. She had worked for Gagosian in both L.A. and New York—including serving as an office assistant to him and Annina Nosei, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s first art dealer. Gagosian’s mentor was Leo Castelli, who represented Warhol.

And, of course, there’s the Velvet Underground. Sonic Youth often cited the Velvets, once managed by Warhol, as a major inspiration. Gordon’s Bad Moon Rising account includes this matter-of-fact observation: “Creedence Clearwater Revival was a faux-southern country band in the same way we were a faux-Velvet Underground band.”

Gordon uses the term “faux” often, in both writing and conversation.

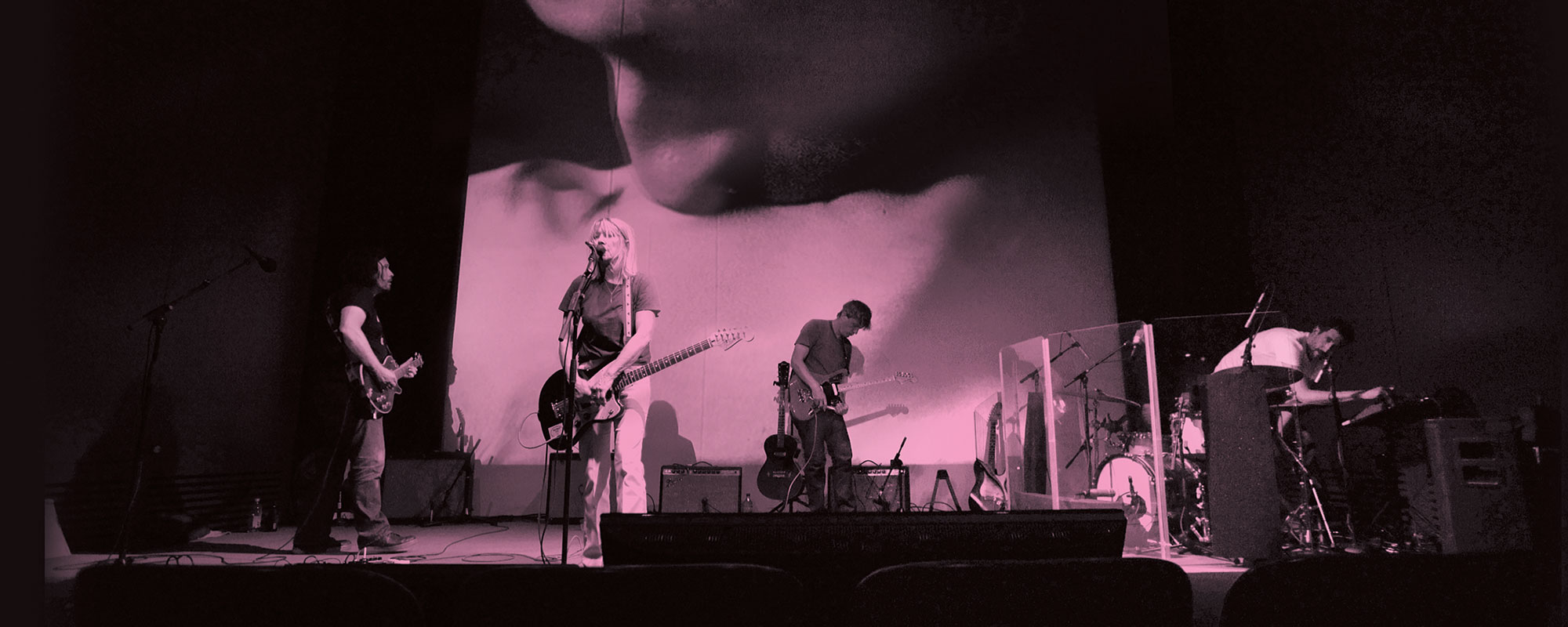

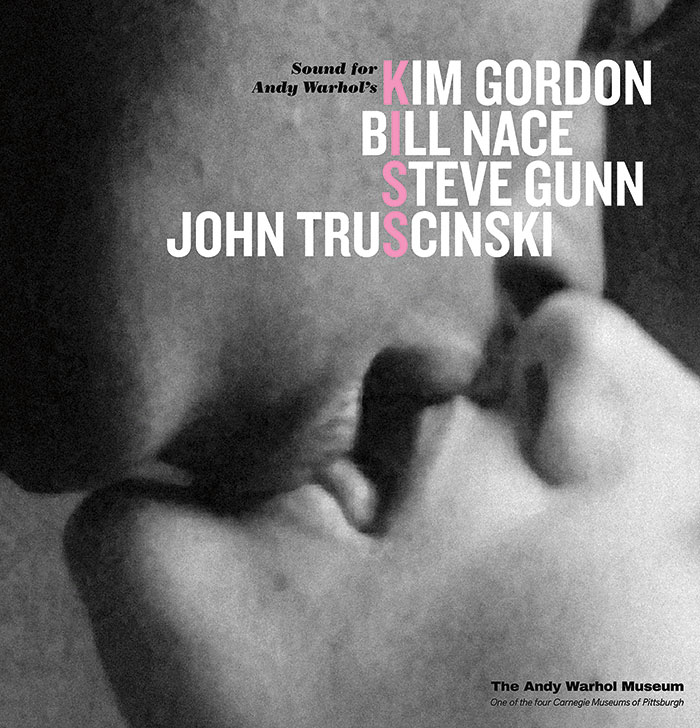

Discussing Kiss, for which she recorded the improvisational Sound for Andy Warhol’s Kiss with John Truscinski, Steve Gunn, and Bill Nace, her partner in the experimental guitar duo Body/Head, Gordon says the film—an hour-long depiction of 14 couples locking lips—appeals to her because of its “fake intimacy.”

Sound for Andy Warhol’s Kiss LP cover

Describing the evolution of her Twitter paintings, Gordon says they started with her Noise Name series—performative, raw works that pay tribute to little-known experimental bands by scrawling their names in dripping black paint. That series led to additional word-focused paintings, with statements such as “The Promise of Originality,” and works she describes as her “faux political hashtag protest paintings,” which exclaim “#Youdon’townme” and “#ThisisIllegal.”

Of the Noise Name paintings, she notes, “I just like the idea of taking something obscure that had little value, in terms of the monetary system, and putting it into the context of a painting where it could accrue value. And the idea of someone buying one, it’s kind of like getting a T-shirt from somewhere you’ve never been. That’s a thing now; people wear T-shirts for bands they’ve never seen.”

In that series and others, Gordon challenges the nature of art and its value, while skewering consumer culture and revealing just how deeply the pop art ethos is ingrained in her subversive, irony-loving psyche. And it’s all wrapped within the boundary-pushing, status-quo-questioning, authority-resisting nonconformist she became while growing up middle-class

in 1960s L.A.

The making of a feminist icon

Gordon says she started seeking ways to thwart expectations even before she had a clear sense of what those expectations were. She would learn soon enough about conformity as she sought to fit in while questioning sexual and class stereotypes and other societal norms. She still raises those questions in her creative endeavors.

The daughter of a sociology professor and a seamstress mother, Gordon says in her memoir that as a youth she was uncomfortable drawing attention to herself, especially because her older brother, who would later develop schizophrenia, demanded so much. She endured his mocking and belittling, but it hurt. Her frustration with her parents’ failure to address the situation compounded the pain. “In many ways,” Gordon wrote, “he erased me, made me feel invisible even to myself.”

What developed “is a look at Kim as an artist who has been creating and developing her artistic practice for 30 years.”

– Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art

Kim Gordon, The Pitch 21 (detail), 2018; Ladies of the Paradise #10, 2016, Courtesy of the artist and 303 Gallery, New York

She learned to channel her emotions into art, dance, and, later, music, which allowed her to rebel in ways she couldn’t manifest elsewhere. She sought the fringe types at college and art school—she graduated from Otis College of Art and Design in L.A.—and was pursuing art as a career before launching the pioneering noise rock band that made her famous.

Gordon suspects Warhol was also more interested in being seen, as in valued and respected, than actually being famous. “There was so much that he hid behind a mask of passivity,” she says, noting he seemed to be conducting a game of tag, and everyone else was it. Like a professional voyeur, he could stand around and watch them play.

In Gordon’s case, fame has always been a source of emotional ambiguity, if not conflict. It wasn’t something she chased; in fact, she resisted being labeled a “rock star.” In her book, she says it feels “dishonest.”

“I like to work … obviously, so much of my identity is just from working,” she says, struggling to express her thoughts while hinting at the peculiar dilemma fame presents: It’s difficult to discuss its downsides without sounding unappreciative of its perks or ungrateful to those who elevated you to that seemingly envious perch.

“It’s kind of a love-hate relationship,” she continues. “I always felt like I wanted to not be that well known, so you can still do things and not carry around so much baggage that you’re labeled in a certain way.”

Gordon wasn’t into being anointed as half of a rock ’n’ roll power couple, either, even though that’s how she and guitarist Thurston Moore, Sonic Youth’s co-founder and her former husband of 27 years, were cast in most media.

Unlike Warhol, who was obsessed with manipulating images in art— including his own—and popular culture, Gordon wasn’t interested in crafting a faux persona. Being from L.A., where fabricating reality is big business, it was yet another way of defying expectations.

Sonic Youth inspired another form of erasure. In trying to “punk myself out,” Gordon admits, she sought to “lose any and all associations with my middle-class West L.A. appearance and femininity.”

DIY Glamour

That concept of appearance figures heavily in her connection to Warhol. In her memoir, Gordon mentions that even though the Sunset Strip was off-limits to her as a teen, she’d always been drawn to the “seediness and sadness” underlying its allure. She appreciated a similar aesthetic in Warhol’s films and his studio, which he dubbed the Silver Factory.

Gordon suggests Warhol’s fascination with Hollywood stars accounts for the glitzy sheen he applied to the scene he created. But it was just that—a superficial masking of reality. “There was a certain glamour around Warhol and his Silver Factory, but if you really look closely at it,” she elaborates, “it was like, ‘Oh yeah, silver spray paint. That really hides a lot.’ I mean, it instantly adds glamour. It’s like do-it-yourself superstardom. You make your own kind of glamour scene.”

Beck notes that Gordon began working with “lo-fi” materials like glitter spray paint early on, expressing an interest in the “silver materiality” that echoes Warhol’s Factory and his Silver Clouds sculptures. Even Sonic Youth’s first big-budget video, for Kool Thing, was filmed against a silver-foil backdrop, which Gordon calls “a nod to Warhol Factory-era East Coastness.”

“It’s like do-it-yourself superstardom. You make your own kind of glamour scene.”

– Kim Gordon, on the Pop world Warhol Created

Just one year after moving to New York along with friend and future art star Mike Kelley, Gordon staged her first exhibition, Design Office, and a year later co-curated an exhibition of musicians for Noise Fest, both at the artist-led White Columns. Art remained central to how she saw and processed the world, but Gordon’s visual-art career would not take off for two decades. Perhaps her discovery that she liked performing—despite having no musical background—distracted her just enough to slow its development.

Sonic Youth came together when she and Moore started dating in 1981. By then, Dan Graham, the artist, writer, and curator who had become Gordon’s friend and mentor, had enticed her to start writing, convincing her that artists have a responsibility to contribute to the larger cultural dialogue.

She also became Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain’s confidante; his wife, Courtney Love, talked Gordon into producing her band Hole’s debut album, Pretty on the Inside. The Beastie Boys’ Mike D invited Gordon to develop X-Girl, a women’s street fashion line, with Daisy Cafritz, sister of Gordon’s pal Julie Cafritz of the band Pussy Galore (and, with Gordon, “anti-rock” band Free Kitten). Following daughter Coco’s birth in 1994, Gordon also got involved in directing and acting.

“When I moved to New York, I moved there to do art and I fell into playing music,” Gordon says. “I felt like, in a way, the next step from what pop [art] did was making comments about popular culture within popular culture, as opposed to being a voyeur on the outside.”

In the early 2000s, Gordon developed her Noise Name paintings, which are inspired by her life in music. When she and Moore split in 2011, Sonic Youth disbanded, giving Gordon even more time to focus on her visual art, though she still records and performs in Body/Head and Glitterbust with Alex Knost. She also released a solo single in 2016.

These days, she lets her muse take her where it will. Lately, she’s been pondering a perceived trend toward treating art as entertainment—“something that you can digest as easily as a commercial or TV show.”

Art as commodity is a subject Warhol knew a little something about, and with Lo-Fi Glamour, it’s almost as if he and Gordon are finally having their long-overdue conversation—hashtags and all.

Kim Gordon: Lo-Fi Glamour is generously supported by Alexa and Adam Wolman.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up