At age 8, Mel Bochner spent Saturday mornings boarding the trolley near his East End home, handing the conductor 8 cents and then traveling alone to Carnegie Museum of Art. It was 1949, and Bochner was headed to his weekly Tam O’Shanter art class. There he met creative kids from all over Allegheny County, and his natural drawing ability thrived on the formal instruction. “A whole new world opened up, and that world was the museum,” he recalls.

When class let out, he learned just as much roaming the cavernous halls of Carnegie Museums of Art and Natural History. His favorite exhibit was the dinosaurs. He remembers sitting on the floor, staring up at museum painter Ottmar von Fuehrer perched atop scaffolding as he brought the Tyrannosaurus rex to life in a mural that once loomed large over Carnegie’s dinosaurs.

This October, Bochner will return to his childhood museum as a participant in its premier exhibition, the Carnegie International. The homecoming is long overdue for an innovator who rejected abstract expressionism and was among the first to introduce language into the visual field.

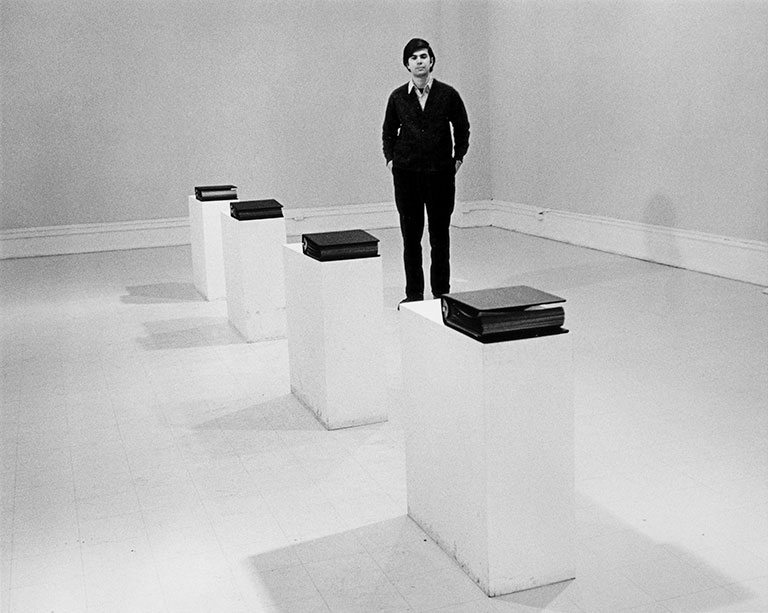

“You cannot study contemporary art and the conceptual art movement and not learn about Mel Bochner. In 1966, he exhibited four three-ring binders loaded with pieces of paper from other artists that he had collected and Xeroxed and called it a drawing show,” says Ingrid Schaffner, curator of the 2018 Carnegie International. “He is a generative figure who has been collected by our museum, who has a major public artwork on the Carnegie Mellon University campus, and yet Mel has never been in a Carnegie International. So, we had to set that situation right. It’s very significant for Mel and very significant for us.”

Bochner’s 1966 show Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art is credited as the earliest exhibition of conceptual art, a movement that forefronts the idea or concept behind a work of art over the finished art object. Bochner, who is also a writer, has long used words and numbers as his material, exploring the limits of language as well as the relationship between language and images by experimenting with how they influence perception. Repetition plays a major role in his work, and he often revisits the same words and phrases. His word paintings are at once playful and provocative, intellectual and ironic.

Mel Bochner in his 1966 show Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to Be Viewed as Art, credited as one of the earliest exhibitions of conceptual art.

Consider his 2008 work titled Blah, Blah, Blah, now on view in Crossroads: Carnegie Museum of Art’s Collection, 1945 to Now and one of several works by Bochner in the museum’s permanent collection. Painted in light blue capital letters against a dark blue background, the word is repeated over and over, oil paint dripping from the edges of some letters.

“It’s a response to the world as it is, the current level of the discourse, the conversation,” says Bochner. “On one level it’s funny, and on another level it’s critical. On a third level it’s political.”

His well-known thesaurus paintings include lines of synonyms that often grow increasingly confrontational as he makes his way down the canvas. A painting titled Go Away begins gently with “go away” and “get lost” and then escalates to “leave me alone” and “scram” before culminating in a profanity.

For the International, Bochner is creating a series of new word paintings, the sum of which the curatorial team imagines will be a “very aggressive greeting” inside the Heinz Galleries. Several paintings will pop up in more unexpected locations throughout the museum. One asks, Do I have to draw you a picture? spelled out in white block letters on black velvet, some of the letters smudged or protruding to create nuance. To build in an element of surprise, Bochner will only say that the other new works are on velvet. “It’s a beautiful surface. It absorbs all the light. It does not reflect. It has all these oddly kitschy qualities, an “Elvis-is-alive” quality. That was inadvertent but not unappreciated.”

Inside his New York studio, Bochner’s process is one of exploration. “It’s like a rope with many strands and you can take apart the strands and reweave them and find different ways of saying things,” he says. “It’s not one thing after the other. It’s many things at once. That’s the fun of it.”

Bochner would distinguish himself as an artist and lover of language after putting in some hard time as the assistant to a sign painter. His father, Meyer Bochner, was responsible for the lettering on shop windows and storefronts throughout Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood, including the well-known Original Hot Dog Shop. Working long hours for meager pay, he set up shop in the basement of the family’s modest house near the corner of Beechwood Boulevard and Wilkins Avenue (“it wasn’t called Point Breeze back then”) and enlisted his son to fill in the letters he had outlined.

“Basically, I apprenticed against my will,” Bochner says. “But I learned a lot, most of all how to work hard.”

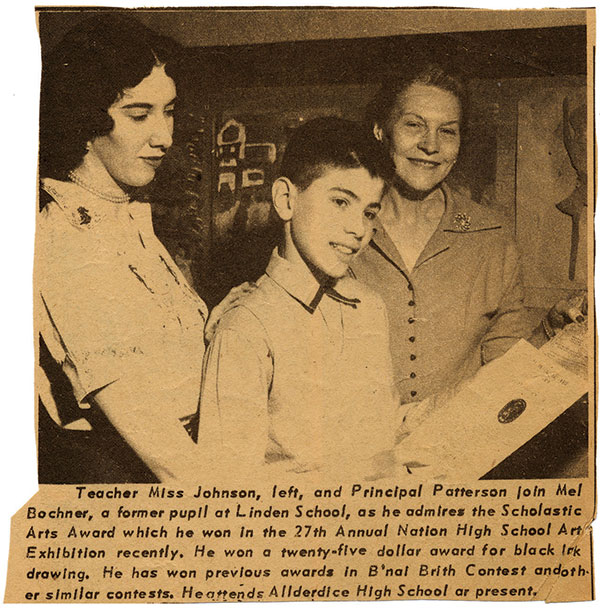

From an early age, the artist’s talent showed through his drawings. As a student at Linden Elementary School, his teachers selected him to be one of two students to attend the Tam O’Shanter art classes, a museum program that will turn 90 this fall and is known today as The Art Connection. Bochner continued taking the classes throughout high school, and, when time allowed, he sometimes set off to explore the surrounding Oakland neighborhood or go to a Pirates game at nearby Forbes Field for 99 cents—or, even better, sneak in for free.

Selected to attend the museum’s Tam O’Shanter art classes in 1949, Mel Bochner won a Scholastic Arts Award for his efforts.

Bochner also remembers viewing the Carnegie International, which occurs about every four years, on class field trips, but it made little impression. He was more enthralled with the tour of the Heinz ketchup factory, coming home with a pickle-pin souvenir.

Even so, the art instruction at the museum awakened something in him. But he wasn’t sure of the path forward. “I didn’t know what being an artist meant,” recalls Bochner. “The closest thing was the covers of the Saturday Evening Post. My father revered Norman Rockwell.”

Of Bochner’s artwork, his father’s favorites were the drawings of Moses and the Ten Commandments he created as a kid in Hebrew school. He was less enamored with the works that would one day hang on museum walls and garner international acclaim. “Success for him would have meant that I became

a doctor,” says Bochner. “There was nothing that would be equivalent. My mother was more appreciative.”

Instead of going to medical school, Bochner studied art at Carnegie Technical Institute, now Carnegie Mellon University (CMU). He says he received an excellent education, but the one thing he didn’t learn was how to make a living with a fine arts degree.

After graduation, Bochner headed west to post-beatnik San Francisco, where he apprenticed at an antiques restoration business, “basically making fake antiques.” After a stop in Mexico, he returned to Pittsburgh and worked as a substitute teacher at an elementary school in Homewood. While he loved the work, teaching didn’t leave enough time for painting.

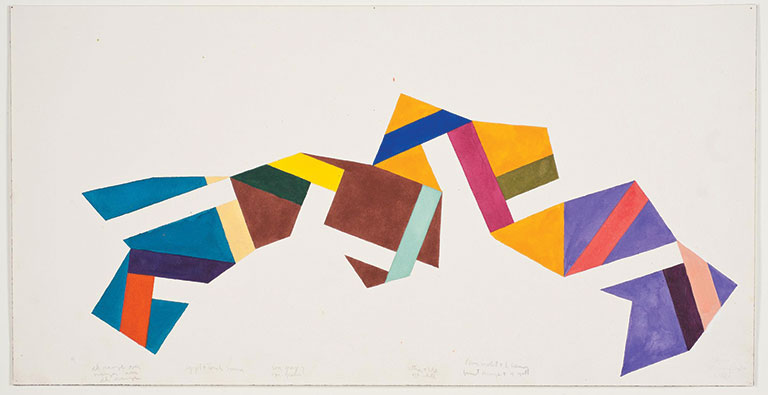

Mel Bochner, Syncline, 1979/1981, William G. Bechman Charitable Trust in Memory of William G. and Beatrice M. Bechman © Mel Bochner

Bochner’s 1979/1981 wall drawing Syncline was among the first conceptual artworks to enter the museum’s collection.

He arrived in New York City in 1964, just as the art scene was exploding with the avant-garde work of Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. “I didn’t know anybody or anything,” he says. “It was all happening above my radar.”

Even after he became acclimated to the New York scene, he was still reaching for something original. His breakout moment came in 1966, when he was asked to curate an art show. But instead of mounting works on the walls, he photocopied the notes, sketches, and diagrams of various artists, putting them in binders displayed on pedestals in the gallery. The show created a sensation, and from there he moved on to words and numbers—and international acclaim as a conceptual artist. But it’s a term he doesn’t like. “All art is conceptual,” Bochner says. “It’s redundant.”

He returned to CMU in 2004 as part of a collaboration with landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh. Together, they created the Kraus Campo, a rooftop installation at the Posner Center that combines art—including Bochner’s trademark numerical sequencing patterns and text—and landscape design. It’s often described as both garden-as-sculpture and sculpture-as-garden.

Today, Bochner is once again making new art for the city that helped shape him as an artist. At 77, he says he has no desire to slow down. “Artists don’t retire.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up