You May Also Like

Curate This ‘We Do Still Exist, and We’re Thriving.’ Objects of Our Affection: GortOut of public view on the third floor of Carnegie Museum of Natural History sits a pair of storied field scientists, John Rawlins and Bob Davidson, their well-loved workspaces bookending a windowless maze of bug cabinets, overflowing bookshelves, and mounting boxes of meticulously prepared specimens.

Within easy reach of Rawlins is a computer, a high-powered microscope, and box upon box of beautifully pinned bugs—moths mostly. Just behind him is his life’s work: some 30,000 drawers filled with millions of butterflies and moths, waiting, as Rawlins describes it, “to be worked.” The prized collections of the museum’s section of invertebrate zoology—aka the bug rooms—reveal an accumulation of breathtaking biodiversity.

John Rawlins (left) and Bob Davidson (above) in the “bug rooms.” Photos: Joshua Franzos

“Weird, showy, subtle—we’ve got it all,” says Rawlins, leaning in, drama in his voice. “Nobody does it like we do it in terms of the numbers, and the really wild, weird stuff.”

Standing among the bugs, Rawlins is in his natural habitat.

Much of the wild, weird stuff he refers to is new to science, the result of 15 collecting trips to the Dominican Republic and three to Haiti. And that’s just in his specialty of Lepidoptera, or moths and butterflies. There are millions more where they came from, and Rawlins knows the museum is sitting on a gold mine of undescribed material that will one day soon inform conservation efforts in one of the world’s most devastated regions.

“We will tell them what the bugs had to say about the debate between preserving new reserves or parks on the border of Haiti and high in the mountains, or down in the desert—which one is more valuable to save,” Rawlins says. “Prioritizing protection. That’s a dream. But it’s doable.”

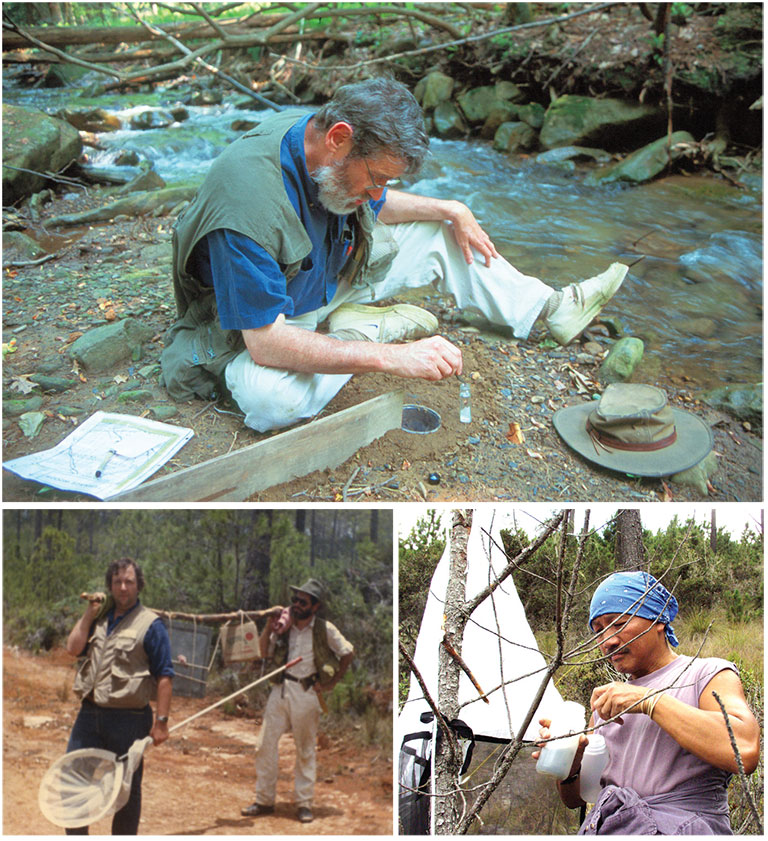

In the spring of 2002, Rawlins and longtime officemates and fellow entomologists Davidson and now-retired Chen Young embarked on a National Science Foundation- funded foray into the ecologically threatened mountainous regions of Hispaniola, the tropical island shared by the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The team, which included colleagues at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, Harvard University, and a number of locally based institutions, collected on every mountain range in each of the four seasons for three weeks at a time. The five-year venture built upon at least a half-dozen earlier trips by Rawlins and Davidson starting in 1987.

John Rawlins, Bob Davidson, and Chen Young in the Dominican Republic.

The specimens and data, now archived in the museum’s collections, have already been used in more than 80 scientific papers by researchers around the world. And now, on a brisk March afternoon about five months before he’s scheduled to retire, Rawlins, who turns 68 in June, is daydreaming about breaking free from his ever-increasing administrative duties as curator and section head to get back to the bugs, to identify and study the butterflies and moths still awaiting their coming-out parties.

“In my emeritus period, I wouldn’t be surprised if I publish almost monthly describing species, mostly from the Dominican Republic, but also from around the world,” says Rawlins, rattling off the far-flung locations of other significant collecting expeditions such as Taiwan, the High Andes of Ecuador, and the central and east African sites of Cameroon, the Upper Congo Basin, and Malawi.

The time is now

The museum’s small, scrappy gang of bug scientists is in a race against time and increasing environmental change. Since Young, Davidson, and Rawlins first arrived at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in the 1980s, they’ve doubled the collection, prioritizing expeditions to some of the world’s most endangered and under-surveyed regions—areas that provide plenty of danger to humans, too.

For the first two decades, the trio spent an average of three months a year in the field; at their peak they spent six months. As a result, roughly 5 million of the 13 million specimens tucked away in the bug rooms still need to be prepared, labeled, and studied—everything from tropical grasshoppers from the Upper Oubangui River in the Congo Basin, to Mongolian crane flies, to ground beetles from Pittsburgh.

“Weird, showy, subtle—we’ve got it all. Nobody does it like we do it in terms of the numbers, and the really wild, weird stuff.” – John Rawlins

A small sample of inspiration: a Cecropia moth caterpillar, crane fly, and green tiger beetle. Photos: Marvin Smith, John Flannery, Katja Schulz

Simultaneously, they and a then-growing support staff, partnered with Charles Bier of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy to track biodiversity at home, began undertaking frost-to-frost surveys in western Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia.

Equally as important—and unlike in the days of the collection’s earliest stewards such as William Holland and Andrey Avinoff—today’s staff look beyond their own specialties and areas of interest.

“When we arrived, the collection was quite nice already, except the earlier collectors concentrated only on their own groups, so the focus was on butterflies,” says Young, a leading expert on crane flies who retired in the spring of 2015 and now lives in California.

“When we were out in the field, we collected everything. That’s how the collection became noticed by other researchers. They knew the Carnegie had all of the new material from all around the world. We were collecting for the whole community. We were thinking big and for the future.”

The Carnegie Museum’s transformation from quiet collector to magnum force on the world stage didn’t go unnoticed, at least partially due to the six degrees of separation from John Rawlins rule in the world of entomology.

The trio in the field at Powdermill Nature Reserve in the Laurel Highlands, and in the Dominican Republic in 1987 and 2002.

“The Carnegie guys collect everything, which is really awesome for the rest of us because they get to some really interesting places that a lot of people haven’t been to,” says Chris Dietrich, a systematic entomologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey, who was first introduced to entomology as a freshman work study student at Carnegie Museums in 1980.

But they don’t stop there, notes Dietrich. Just as Rawlins and company have had to be equally as assertive in seeking out external funding to support their brand of salvage collecting—driven by the mantra that there’s never enough bugs—they also actively recruit external support to work the specimens, all in the name of science.

“They’ll actually call you up and say, ‘We just got a whole bunch of this particular group of insects from the Dominican Republic, do you want to look at them?’ And you say ‘of course I do,’ and they’ll pack them up and send them to you,” adds Dietrich. “I think that’s one of the big differences that [Rawlins], in particular, has made in leading that department. He’s really proactive about reaching out to researchers and keeping track of who in the field is doing what, and who might need specimens in a particular group. It’s rare, and it makes a difference on a broader scale.”

“When we were out in the field, we collected everything. That’s how the collection became noticed by other researchers.We were collecting for the whole community. We were thinking big and for the future.” – Chen Young

Not everyone appreciates this aggressive style of building a collection. Even in-house colleagues in other science sections weren’t—aren’t—always supportive of this collect-now, work-the-specimens-later approach. With ever-shrinking science staffs at natural history museums around the country, it does have its administrative drawbacks. But the urgent argument for collecting before it’s gone is a powerful one, and under Rawlins’ leadership the department has secured a record $4.4 million in external funding since the 1990s.

“Some people don’t agree with it because it’s meant there’s a lot of stuff to take care of and find room for, but what’s the alternative?” Davidson asks.

“The alternative is to do what a lot of other institutions have done, and that’s to clean your own nests and database all of your specimens. But, when that’s complete and you go out to get more, it’s all gone, it’s all extinct. So we made a calculated and sometimes unpopular decision to continue collecting while we still can, and let the next generation take care of it and clean it up and database it. The point is the specimens are here—and quite possibly nowhere else.”

Hooked on caterpillars

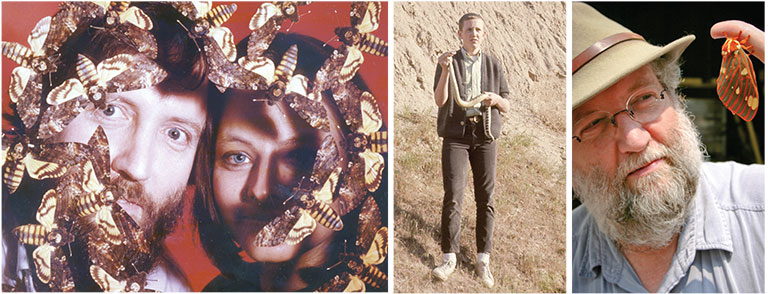

Rawlins didn’t get to his first bug until age 25, a rarity for insect lovers. He was first taken by snakes.

Having grown up on a remote sheep farm in eastern Oregon, Rawlins was immediately drawn to zoology, the branch of biology that focuses on the structure, function, behavior, and evolution of animals. The family farmhouse included a floor-to-ceiling library stuffed with, among other things, his mother’s National Geographic magazines, which he devoured, cover to cover. He studied at Oregon State University before going to graduate school at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where he met a charismatic mentor who changed his trajectory.

“I met this old gentleman at Cornell, Dr. John Franclemont. I watched him raising caterpillars in the lab,” says Rawlins. “Discovering that I, too, could go out and get a known female and get her to lay eggs and that I could raise them, I started raising them and never stopped.”

In fact, the laborious practice of discovering life histories in the field—rearing moths and butterflies from egg, larva, and pupa to adult—has become a trademark for Rawlins.

“He was a pioneer of sorts in this regard,” says Jacqueline Miller of the University of Florida, who, like Rawlins, is an expert on Caribbean and tropical moths and butterflies. “He was the first I met who did it. He helped set the standard. … Today it’s part of students’ coursework.”

In 1990, John Rawlins was a scientific advisor for the Oscar-winning thriller The Silence of the Lambs, starring Jodie Foster (pictured above with Rawlins) and Anthony Hopkins, in which a scene was filmed in the bug rooms. Rawlins’ first love was snakes. He’s shown here at age 15 and after becoming a full-fledged bug man.

What’s gleaned from the process aren’t the kinds of discoveries published in a high-impact journal, but they provide fundamental information you can’t tease out in any other way. By observing the life cycle, you document the plant that the caterpillars are eating, the role the caterpillars play in their environments, and whether or not they face—or pose—any threats.

It requires the same level of patience and attention to detail that makes Rawlins, Davidson, and Young so good at systematics, the study and classification of lineages whose features differ among species. For instance, Davidson, a leading expert on ground beetles, officially known as Carabidae, can determine whether a beetle just discovered in Pennsylvania is one whose eating habits make it a danger to local forests, or if it’s just a harmless species that merely looks a lot like the destructive kind.

Why are insects so ecologically important? “Because there are so blessed many of them,” Davidson says, noting that when it comes to studying how the world is changing across habitats, entomology is a science with a unique take on biodiversity. Worldwide, estimates range from 5 million to 30 million species, with only about a million identified. Some insects carry disease, many are all-important pollinators, and most are hyper- sensitive to climate change. Some can also cause devastating agricultural damage.

“We’re the ones who answer the question, ‘what bug is it?’” says Rawlins. “We’re a lookout for bad bugs and all the things bad bugs can do. And we have the power of the big comparative collection in our corner. The problems caused by the bad bugs are, largely, best solved by the good ones.”

When federal authorities turned up a potentially disastrous agricultural pest along the outskirts of southern Miami, they speed-dialed Rawlins, an internationally renowned moth expert. With millions of dollars of American agricultural crops in the direct line of fire, what happened next unfolded like a fine-tuned military maneuver.

During a routine U.S. Department of Agriculture survey, the government had captured the enemy: a type of moth destructive to corn, wheat, and soybean crops, commonly known as the old-world armyworm, or cutworm. The question was: Were there more where that came from?

By way of FedEx, thousands of dead moths arrived on Rawlins’ doorstep. Were they or weren’t they “tiny little terrorists,” as he likes to refer to invasive species? “Thankfully, no,” says Rawlins.

In 2006, Rawlins and team established the Biodiversity Services Facility (BSF), through which they help the U.S. Forest Service and various state agencies identify unwanted invasive insects such as the wood-boring bark beetles that decimate forests. Bob Androw, a scientific preparator who jokes that he’s in his 22nd year of a one-year position, oversees the BSF’s sorting and identification process. Jim Fetzner, the department’s assistant curator and resident crayfish expert, developed the unique database that powers the tool.

“What we offer is not easy to match. You get a lot of bang for the buck,” says Androw, referring to the department’s comparative collection and expertise to translate it. He identifies some 60,000 specimens a year through BFS, and representatives of all of them make their way into the Carnegie Museum collection. “These scientific services are one way of making our knowledge and our collections available to the public in solving real problems,” says Steve Tonsor, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s director of science and research.

For the love of bugs

Rawlins’ legacy extends beyond any one discovery, program, or service, says Tonsor.

“John took on this wonderful collection, but in the process sort of sacrificed himself to it. But I would say joyfully so, because he saw the immense value of the collection and of the museum as a whole. There are a lot of curators in the world who only care about their own collection. John, instead, has been an ambassador to the world for representing the value of collections and love of the natural world, and of understanding the diversity of life.

“John’s just the quintessential entomologist and he’s so good at communicating his excitement about insects and their diversity. It’s infectious. I certainly was infected.” – Chris Dietrich, a systematic entomologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey

“John has a big heart,” Tonsor adds. “Some people have a big heart and just sort of stand back and watch. John has a big heart and he gives it away on a regular basis. All the people who are reached by the museums, as well as the butterflies and moths of the world—he deserves all of their respect and gratitude.”

Rawlins’ vast network of “bug people,” which stretches far and wide, agrees.

“John’s just the quintessential entomologist and he’s so good at communicating his excitement about insects and their diversity,” says Dietrich, who credits Rawlins with inspiring his career choice. “It’s infectious. I certainly was infected.”

Closer to home, Charles Bier, the senior director of conservation science at the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, credits Rawlins as both a willing collaborator and teacher.

John Rawlins in his element: turning the next generation on to the natural world. Jane Hyland (seated at left), a longtime scientific preparator and illustrator in invertebrate zoology, is credited with much of the preparation of an always growing collection.

“The amount of time John has given people is pretty amazing,” says Bier. “A lot of scientists go into their corner and look through their dissecting scope and do their thing. That’s not John. He’s a natural teacher. John’s professional and personal time—there’s no boundary there. That’s something that has helped me to grow as an ecologist and a conservation biologist, just to have access to John’s experience and intellect.”

For Rawlins, it’s all about the bugs.

Filling in the gaps of science is expensive, oftentimes nasty and unglamorous work, and occasionally precarious. Rawlins and team were collecting in the Congo in 1995 when civil war broke out. They’ve been held at gunpoint, contracted malaria, survived scorpion bites and even an African rebel prison cell.

“That explains why I’ve been in Costa Rica for 10 days total,” he says. “Costa Rica is a wonderful place with wonderful habitats; it’s little America, it’s an easy place to go. But somebody has to check what’s on the backside of that mountain peak over there, and let’s go see what’s up there, too.

“It’s been a wild ride,” continues Rawlins, who as part of his retirement dreams of return trips to Hispaniola—if not for future Carnegie scientists, for eager takers at other institutions.

“What would we find there now, 20 years later?” the bug man wonders. “That’s what we have to find out. The hunt goes on.”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

Science & Nature