Editor’s note: Beginning with this issue, Carnegie magazine will feature items from the magazine’s 98-year-old archives. The following is an excerpt of an article written by Dr. M. Graham Netting, former director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, about the animal portraiture collection that he established, which is also featured on page 26 of this issue. The original article appeared in the November 1979 issue.

I have long expected that anthropologists would find in some cavern frequented by early man a mysterious assemblage of objects tucked away in a stygian niche. These would be categorized according to standard procedure, as ceremonial objects, the catchall designation for all artifacts whose true function evades explanation. I can even forecast some of the items that would be represented in the horde, with exact composition somewhat varied by location—a piece of veined quartz, a concretion, several sea shells, an iron nodule, perhaps a gold nugget or piece of amber. And being ancient enough to remember traveler’s curiosa in corner whatnots in Victorian parlors, I can second-guess young anthropologists and assert that early man, like his descendants ever since, suffered from pack-ratting.

The collecting urge is most catholic and unrestrained in childhood. In many persons it becomes submerged during school years and pursuit of a living. Some individuals achieve wealth and then begin to amass the great personal collections of art, books, or whatever that eventually enhance entire galleries in great museums; others, less affluent, specialize in inexpensive or yet unappreciated materials—the rubbish collector who salvaged Toby jugs, the visionaries who saved samples of barbed wire, the much traveled scientist who saved air-sickness bags—intriguing examples could be multiplied geometrically. Finally, there is a much smaller group so infected by the collecting urge that they jump from childhood into professional collecting with scant concern for their future—they become curators, or keepers of collections, and eschew both high salaries and the chance of selling personally assembled collections at greatly appreciated values.

Curators, however, and some advanced amateurs, for whom collections are the prime focus of daily life, rather than an off-hours hobby, have the rewarding satisfaction of utilizing collections for a variety of scholarly and research purposes of inestimable value to society. Any large grouping of related but dissimilar objects, either products of nature or works of man, may impress the eye, but no collection achieves its ultimate potential until it is studied and interpreted by successive generations of scholars.

For many years, I had the personal delight of adding to the herpetological collections of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and studying and publishing upon some aspects of these collections. Then I had the administrative responsibility for the museum as a whole and the new challenge of finding support for the orderly growth of all the collections and their utilization for research, exhibition, and education.

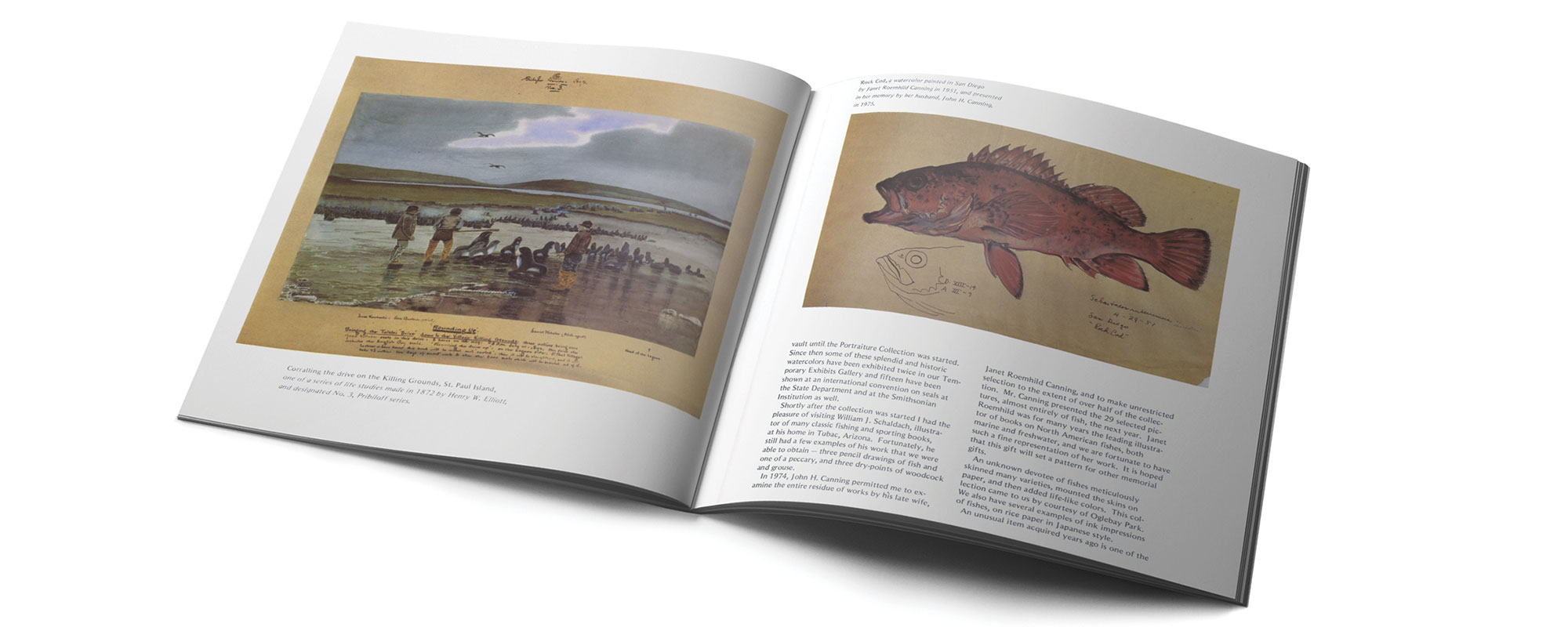

Now I am engaged as a volunteer in assembling a relatively new collection and also in preserving some remnants of the museum’s history. Unlike other collections of the museum, vast in scope and internationally recognized, both the collection of nature portraits and the archival materials have only incipient greatness. They have already proved useful in many ways—for public exhibitions here and in other institutions, for illustrations in publications, and as source material for articles and lectures. They will not become truly significant, however, until artists and illustrators feel that they must contribute examples of their work in order to be represented, and until donors give or bequeath paintings, photographs, or memorabilia that cry for the long-term custody and scholarly utilization that only a museum can provide.

Receive more stories in your email

Sign upTags:

From the Archives