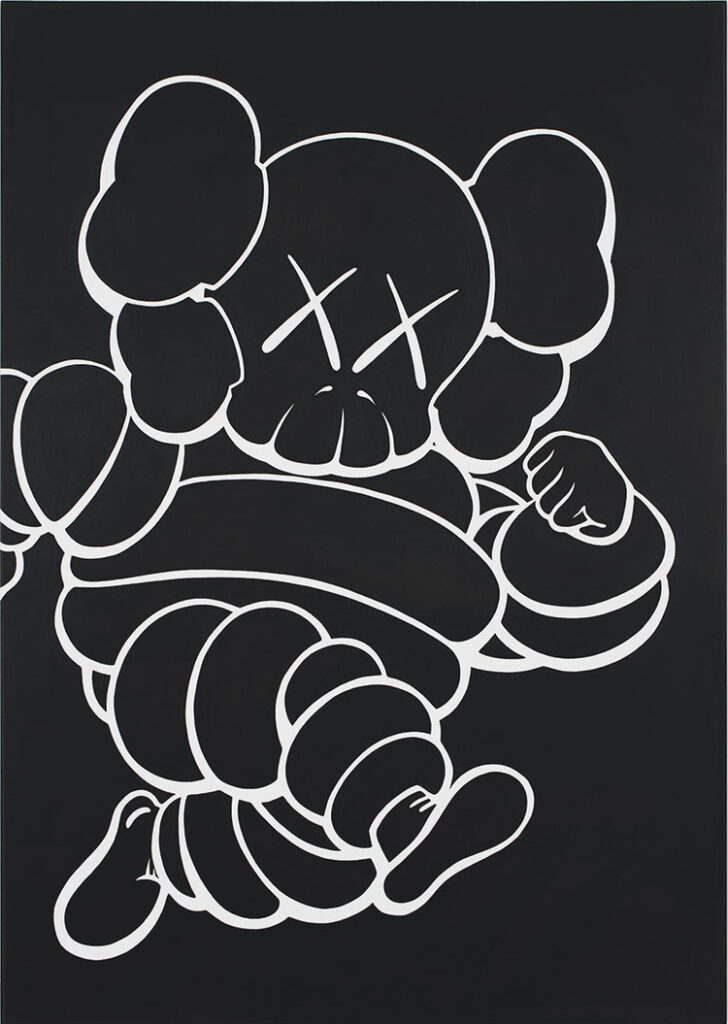

The sculpted figure known as COMPANION is lying face down on the floor of The Andy Warhol Museum, arms at its sides, positioned in a straight line from head to toe. The character’s broad head is cartoonish, like a flattened skull with crossbones jutting from the sides like ears. The shoes, which resemble the bulbous cartoon feet of Mickey Mouse, are extended “laces down.”

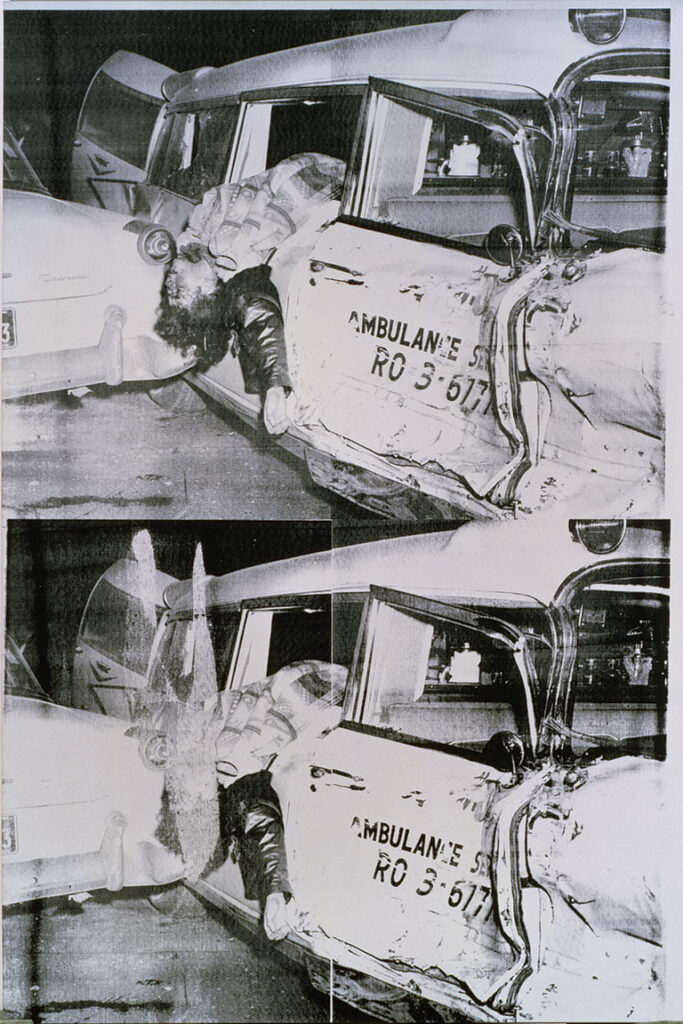

It carries the signifiers of a children’s cartoon character while emoting more somber human feelings: Is it the acquiescence of total relief or utter hopelessness? Perhaps COMPANION’s not even resting, but dead—like the person in the images next to it, in Andy Warhol’s Ambulance Disaster. Hung on the wall above COMPANION, Ambulance Disaster is made of two nearly identical pictures, from photographs of a 1960 automobile accident—a dead body, thrown halfway over the window of a crumpled ambulance.

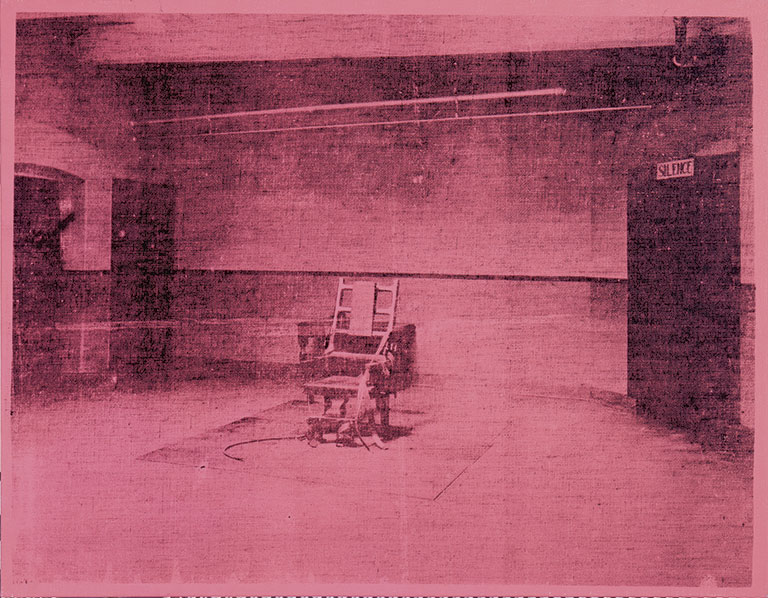

The sculpture COMPANION 2020 by the artist Brian Donnelly, better known as KAWS, and this definitive piece from Warhol’s 1960s Death and Disaster series seem like grim outliers from two artists better known for bright colors and pop-culture inspiration. But as The Warhol’s 30th anniversary exhibition KAWS + Warhol aims to show by bringing these two iconic artists together for the first time, there is another side to each of them—a darker side.

Warhol and KAWS are both often misinterpreted because they use pop culture and bright colors; because young people are attracted to the work. People think their work is light, or even superficial, and I think that’s far, far from the truth.

–Patrick Moore, Former director of The Andy Warhol Museum

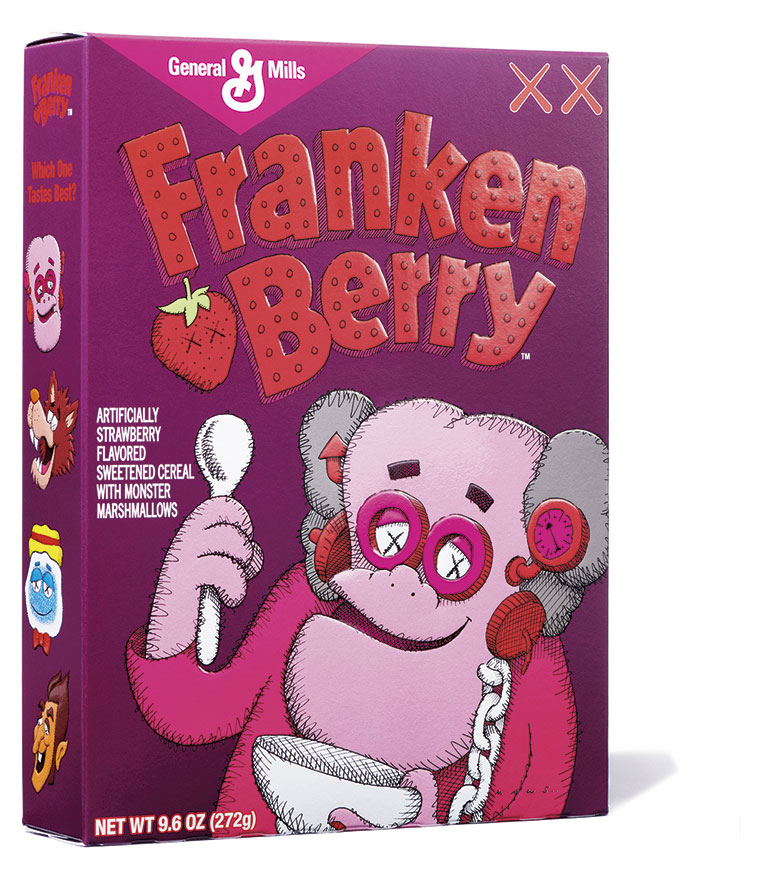

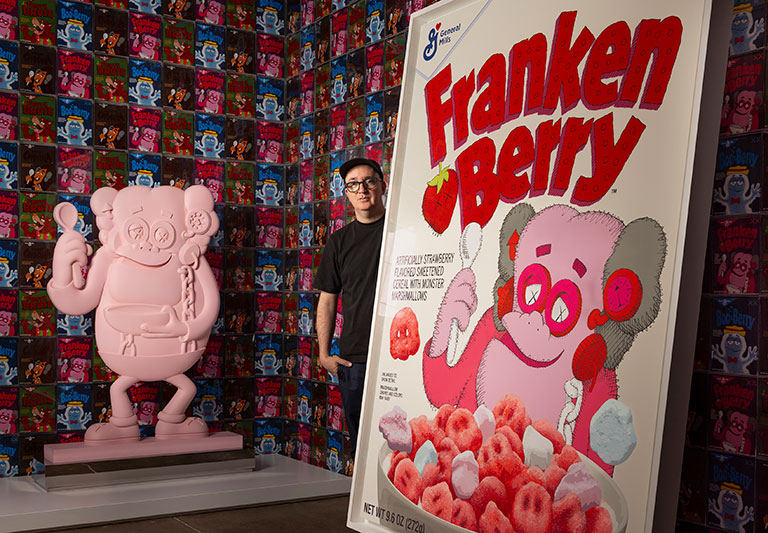

KAWS and Warhol have a lot in common, despite being generations apart. Like Warhol, KAWS continually breaks down the barrier between art and commerce, equally adept at exhibiting in major international galleries and selling T-shirts and figurines featuring COMPANION and similar characters. KAWS started his career in New York City as a graffiti artist, just like Warhol’s young friends Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. And KAWS’ collaborations, such as the one with General Mills to make mass-produced cereal boxes, takes the Campbell’s soup-can aesthetic one step further—moving KAWS’ artwork outside gallery spaces and onto supermarket shelves.

But that’s not the only common thread connecting the two.

“Warhol and KAWS are both often misinterpreted because they use pop culture and bright colors; because young people are attracted to the work,” says Patrick Moore, former director of The Andy Warhol Museum, who was the curator of KAWS + Warhol. “People think their work is light, or even superficial, and I think that’s far, far from the truth.”

KAWS + Warhol shows these two artists not as pop phenomena or brothers-in-mass-market, but as subtler voices for the anxious. Not as celebrity-beloved trendsetters—though they are—but as observers of a generation that simply has seen too much and would so love to briefly close its eyes.

Pop Icons, Misunderstood

“I’ve always gravitated to Andy Warhol,” KAWS says from his studio in Brooklyn, New York. “When you’re young, you tiptoe into artists, and, aside from Van Gogh and the artists schools push on you as a child, it’s Warhol who’s one of those that really hits you first. He has such a free, open mind to different media and to occupying spaces—he opened a lot of doors for my generation, and for artists like [Keith] Haring, who in turn opened doors for me.”

Warhol’s silkscreens and Haring’s dancing, twisting figures have become fully integrated parts of Western culture—not just artworks, but also some kind of pop folk-culture that can be found on T-shirts in Urban Outfitters and television commercials aired during the Super Bowl. It’s the same with KAWS’ artworks, designs, and toys, so ubiquitous from New York to Tokyo that they’ve grown far beyond their creator.

Born in New Jersey in 1974, KAWS moved to New York City in the 1990s, working in commercial illustration and animation as well as his sideline in illegal street art. His early day-job work on animated TV shows (such as 101 Dalmatians, Daria, and Doug) and his graffiti bled together into a kind of artistic gumbo that evokes Disney and The Simpsons, Michelin Man and Bugs Bunny. Eventually, a recognizable form came into being: a series of characters—COMPANION, BENDY, ACCOMPLICE—that are part-humanoid, part-cartoon, with X’s for eyes like dead comic-book drawings. The ever-repeatable images in his paintings and sculptures, album covers and toys are manna to a global, digital generation for whom images matter perhaps more than they do to baby boomers or even Generation X.

Just as Warhol was initially derided for his Campbell’s Soup Cans, KAWS’ exhibitions are sometimes met poorly by parts of the art world. But neither artist makes work that is simply a shallow celebration of capital, which mass media and advertising might imply. To Moore, Warhol and KAWS both convey far deeper sentiments; sentiments often bathed in the darkness of anxious times.

“We live in a world of images—more than even Warhol could have imagined,” says Moore. “But these two artists are very aware of the dark side of image culture—where you’re looking at things but not really seeing them. They’re offering up images that are candy-colored, and that have popular-culture resonance for us, but then have a secondary meaning that’s more critical.”

To this end, KAWS + Warhol includes some of the most familiar images in each artist’s canon, available for reinterpretation. For example, the pairing of Warhol’s film Blow Job with KAWS’ sculpture of COMPANION or KAWSBOB (a kind of Spongebob Squarepants with KAWS’ signature X’d-out eyes) emphasizes the grotesque side of Warhol’s work. In this context, Blow Job star DeVeren Bookwalter suddenly appears death-like, eyes drooping, practically forming X’s.

Works from Warhol’s Death and Disaster series, such as the ambulance paintings and silkscreens of an electric chair, are juxtaposed with sculptures of COMPANION such as GONE, in which the figure carries the broken body of a KAWS-style character like Grover or Elmo from Sesame Street.

Marianne Dobner is curator at Mumok, the Museum of Modern Art in Vienna, Austria, who has written on and curated exhibitions of Warhol, and who contributed an essay on KAWS and Warhol to this exhibition’s catalog. To Dobner, there is a key artistic category that ties the two men together: “the cute.”

“The cute means it’s something very easy to connect to, and yet if you keep digging, there’s something that criticizes society as a whole,” says Dobner. “Look at the Death and Disaster series, the electric chairs and accidents [from 1960s America]. COMPANION feels like we’re in a similar moment now—like there’s so much going on we can’t even find a proper way to talk about it.”

Consider how both artists render dark subject matter such as skulls, Moore says.

“It’s the mark of a great artist that they take a subject that’s actually quite morbid, but through color and shape and form they turn it into something irresistible.”

Fun With Cereal

When presented in context, Warhol’s influence on KAWS becomes more apparent. And that inspiration isn’t just skulls and colors; it’s as much about Warhol’s approach as any of the artist’s actual pieces. Part of that is a passion for exploring different ways to make art, regardless of the medium.

“With Andy, if he’s working on film, that’s what he’s doing—he’s a filmmaker,” says KAWS. “If he’s doing an advertisement, that’s just part of his practice. And I think he’d just expect people to, you know, catch up!”

KAWS and General Mills, KAWS Franken Berry Limited Edition Cereal Box, 2022

© KAWS, Photo: Brad Bridgers

This includes collaborations with musicians. Warhol managed The Velvet Underground & Nico, the seminal 1960s proto-punk album for which he made the famed “banana” cover art. KAWS has 808s & Heartbreak, Kanye West’s game-changing 2008 hip-hop album, for which he designed images bursting with colors and typically KAWS-bendy icons. And while Warhol made renowned ads for magazines and the fashion industry in the 1950s, KAWS’ collaborations with Japanese fashion brand UNIQLO and Disney have turned the 21st century into a world of X’d-out eyes. Their album covers and ads may not be featured in KAWS + Warhol, but there are other ways in which Warhol’s ad-obsessed work and KAWS come into play.

One example includes new works that KAWS will debut in The Warhol’s 30th anniversary exhibition—a series of large-scale paintings of cereal boxes. In 2022, KAWS worked with General Mills to make new KAWS versions of their beloved monster-themed cereal boxes such as Franken Berry and Count Chocula, which are well known to anyone who grew up in the Saturday morning cartoon era. (KAWS was such a fan that, when approached to collaborate on a different cereal for GM, he immediately asked about the monster cereals.) Limited-edition cereal boxes sold in stores with the pink Frankenstein-esque Franken Berry, for example, showed the character with COMPANION-styled skull-and-crossbones head and X’d eyes. Now KAWS has painstakingly reproduced those designs as wall-sized paintings.

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua Franzos“They’ve been on the wall for months,” he says. “It seems so straightforward—reverse engineering what I did for the cereal box. But those are ink drawings scanned into the computer, and now here I’m hand painting all these little lines which, at an 8-inch-by-10-inch scale is just a crosshatch with a pen and takes minutes. So this is months of just redrawing all of that—paying attention to the line weight. It’s fun. It’s therapeutic.”

Part of the project included plastic toys like the ones cereal boxes contained in his childhood. And as part of the exhibition, KAWS has recreated those toys as bronze sculptures, similar to the painting approach.

“Warhol was, obviously, very interested in this kind of work,” says Moore. “KAWS has taken that to a whole other level. You could walk into any grocery store and buy those KAWS cereal boxes, and now, to walk it back into a fine art context with these paintings and sculptures—it becomes like a hall of mirrors between things that are unabashedly commercial and those which are part of the highest level of the art world.”

A Fruitful Pairing

To celebrate The Warhol turning 30 years old, it seems appropriate to do what the museum’s namesake might’ve done and bring together his work with that of the new generation.

The comparisons between Warhol and KAWS are so fruitful—whether it’s their more apparent interests in ignoring tradi- tional boundaries, or the dark “cute”-ness that Moore and Dobner find so compelling. The exhibition also creates a juxtaposition that could be seen as a collaboration between the two artists, their works shining new light on one another that gives rise to new interpretations—and new audiences.

“KAWS has an incredible drawing power with younger viewers,” says Moore. “When Warhol was in the last years of his life, he connected with and made collaborative works with Basquiat and Haring, and he got the idea that to remain relevant, I need a relationship with younger artists who will inspire me, and who I can bring attention to. That’s a strategy baked into Warhol’s life. He wanted to remain relevant, and one way to do that was to work with younger artists.”

Included in the exhibition is a painting called TIDE, which shows COMPANION barely floating—or perhaps not; perhaps sinking—in a moon-lit ocean, no shore in sight. The depth of color, the significance of the moon and its swathe of light across the water, the stillness of this image is comforting despite its potentially unsettling message. Similar to some of Warhol’s silkscreen portraits, COMPANION is like a jolly death mask of celebrity.

My work is very personal. I don’t approach it trying to create dark undertones. I feel like there are just a lot of reactions to the environment in my life, and these are attempts to create things from those reactions that are inviting and have empathy.

–KAWS

“To have these two big figures of the art world talking to each other—it almost feels like propelling Warhol into today,” says Dobner. “For me, those COMPANION figures feel almost like an avatar for myself, just like the Death and Disaster works were decades ago. It’s like me staring at the news—that feeling that we need to do something, and not knowing what we could do.”

What might be seen as an uncanny ability to give the audience its avatar could simply be something KAWS and Warhol exude: respect for the viewer. Neither one feels the need to tell the viewer what they’re seeing.

“My work is very personal,” says KAWS. “I don’t approach it trying to create dark undertones. I feel like there are just a lot of reactions to the environment in my life, and these are attempts to create things from those reactions that are inviting and have empathy.

“The work Andy created is a lot more guarded; cooler. With the work that I make, it’s myself. There’s no façade. I’m just a person making work.”

KAWS + Warhol is presented by Uniqlo. Lead support is provided by Nemacolin. Generous support is provided by Jim Spencer and Michael Lin, and Kathe and Jim Patrinos. Additional support is provided by Carnegie Corporation of New York, and Steven and Lynda Latner. The Warhol’s exhibition program is made possible in part through support provided by the Curatorial Vision Fund. Contributors include Scott M. Mory, and Cris and Cindy Turner.