The tapes just sat around for a while, waiting. More than half a century passed between plays as they sat in Andy Warhol’s offices, later moved in boxes to dusty basements and, for the past few years, to the archives of The Andy Warhol Museum. In that time, the people involved in their making became icons: the ultimate art-rock band, the Velvet Underground; the Cold War chanteuse, Nico; the producer and great American artist, Andy Warhol. Likewise, the music that began life on the tapes would take on iconic status, eventually becoming The Velvet Underground & Nico—one of the most influential rock albums of all time.

When Matt Gray, The Andy Warhol Museum’s director of archives, first saw the words “Velvet Underground” on two quarter-inch reel-to-reel tapes in the museum’s archives, he had them digitized to discern what they were. It proved a revelation: the original New York City recording sessions that are the foundation of that iconic album. Now, in an exhibition curated by Ben Harrison, senior director of performing arts and programming, in collaboration with Gray and director of film and video Gregory Pierce, visitors can immerse themselves in the world from which one of the most famous works of American rock music emerged.

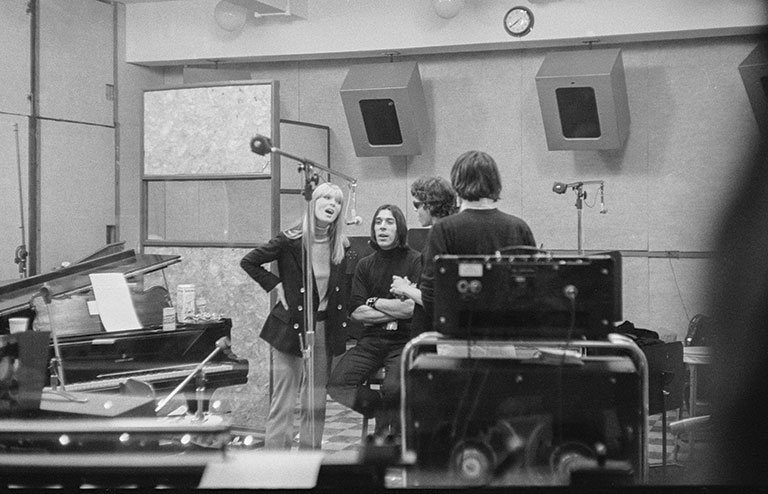

Steve Schapiro, The Velvet Underground Recording Session for The Velvet Underground & Nico, Nico and John Cale with Lou Reed Profile, New York, 1966, © Steve Schapiro, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

It was a brief and intense partnership that took shape in the creative heart of mid-’60s New York City and flared for just 16 months, but changed music forever. Through images, films, artworks, and—of course—hearing the original music of the Velvet Underground on the tapes for the first time anywhere, The Velvet Underground & Nico: Scepter Studio Sessions will illustrate those fiery days, weeks, and months.

“It was like a bright burning star,” Harrison says. “All these personalities, this friction, this energy happens and then it’s gone. That’s what we’re trying to capture—those 16 months.”

Explosive Collaborations

In 1965, Andy Warhol was one of America’s best-known artists, enjoying both artistic and financial success. So, being Warhol, he changed everything.

“It’s late 1965 and, at the peak of his fame, Warhol retires from painting,” says Harrison. “He says, ‘I’m done with this! I’m going to focus on filmmaking!’ And he wants to plug into rock music, too, because there’s this soundtrack that’s always playing at [Warhol’s studio] the Factory and he understands that this is what’s most appealing to young people.”

In December 1965, filmmaker Barbara Rubin and Warhol associate Gerard Malanga brought Warhol to Café Bizarre in Greenwich Village to see the Velvet Underground play. It was something at first sight: Love? Envy? Disturbance? The Velvet Underground wasn’t like the other coffee-house bands—they weren’t like any other bands. Singer Lou Reed was a street-corner garage-punk turned poet; Welsh bassist and violist John Cale came from an experimental music pedigree, having worked with John Cage and La Monte Young. Guitarist Sterling Morrison was inspired as much by raga and noise as the blues that owned rock music at the time, and drummer Maureen “Moe” Tucker bashed out rhythms standing up, her drums turned on their sides. It was loud, occasionally atonal, minimalist rock with dark, poetic lyrics about drugs and sex. It still stands out as odd and incomprehensible to many people, even today.

“It was like a bright burning star. All these personalities, this friction, this energy happens and then it’s gone. That’s what we’re trying to capture—those 16 months.”

– Ben Harrison, Senior Director of Performing Arts and Programming

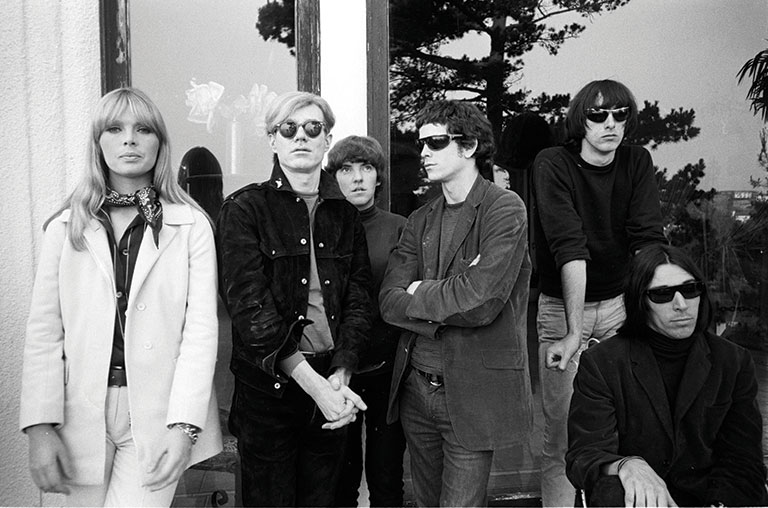

Steve Schapiro, Warhol, Nico, and The Velvet Underground, 1966, © Steve Schapiro, courtesy of Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

Warhol was smitten, and he quickly subsumed the group into his fold, becoming their “manager,” at least in the way Warhol might manage.

“What is management?” asks Harrison. “Maybe it meant buying them equipment; it certainly meant inviting them to the Factory to rehearse and become a sort of house band. Warhol was also interested in creating these very ephemeral performance events; these happenings.”

Warhol launched a series of events called Andy Warhol’s Up-Tight and, later, Exploding Plastic Inevitable (or EPI). These involved experimental films, light shows, dancers, and, providing the anarchic soundtrack, the Velvet Underground. The EPI was successful enough to go on tour across the United States, with alternately raving and damning reviews. But even the most gestational events were exciting enough to raise the idea: This band should make a record.

A Warhol acquaintance, Norman Dolph, worked for Columbia Records and saw the potential in releasing an LP under the auspices of Warhol’s artistic vision and media savvy. The two split the costs and, just as EPI was about to launch its tour, got the Velvet Underground into a studio.

Scepter Studio was located at 254 W. 54th St. in Manhattan—a location that resonates today more from its later use as the infamous disco Studio 54. It was a ramshackle space owned (though rarely used) by soul label Scepter Records. In the spring of 1966, the Velvet Underground, along with the German singer and actress known simply as Nico, recorded nine tracks of alternately feedback-laden noise-rock and eerily touching and dark torch songs.

Andy Warhol was the album’s producer. What this seems to have meant was not that Warhol—with little musical or recording-studio acumen—was calling the shots so much as that he told the engineer and “real” producers to let the band do whatever they wanted. The only person who could tell them what to do was Warhol himself, and he had two demands. First, the Velvet Underground would be augmented by the chilling-yet-sexy voice of Nico, whether they wanted it or not. (They didn’t at first.) And second, Warhol would have full artistic control over the resulting album’s artwork.

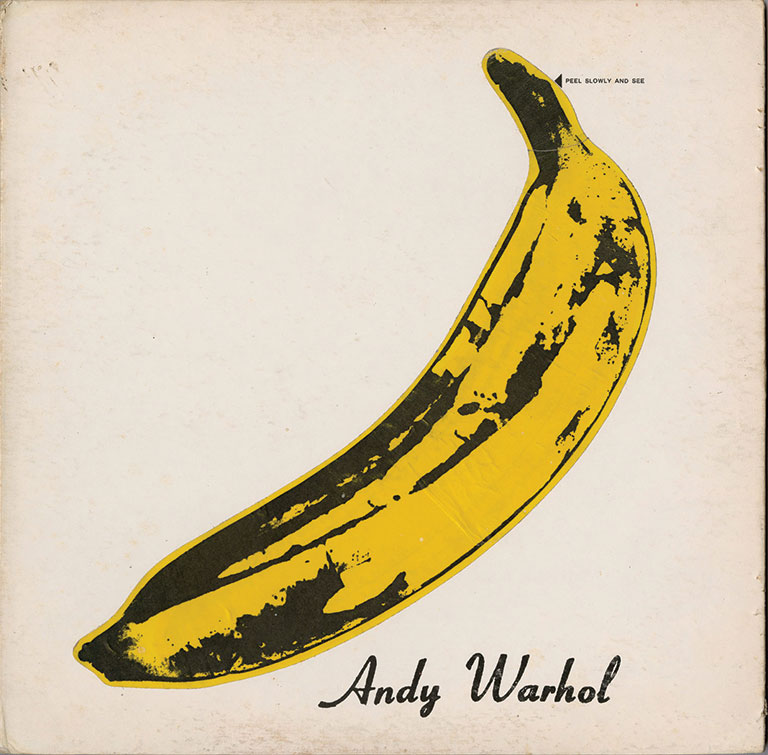

The album, The Velvet Underground & Nico, which was released a year later, drew from these Scepter sessions as well as later sessions in California and New York. Some of the recordings came straight from Scepter, while others were re-recorded, or added to. The artwork Warhol insisted on has become one of the most identifiable rock images of all time: a banana with a stick-on peel that could be removed to whatever degree by each album owner.

Much of what was recorded and shed in the original Scepter Studio work went unheard for decades as the tapes were thought to have disappeared. In fact, they had. But they weren’t thrown away or destroyed. Rather, they’d disappeared into the whirlwind of Andy Warhol.

Boxes of Warhol

Gray’s job at The Warhol is Sisyphean in nature. As director of archives, his task is to survey, track, and understand the artist’s objects that had been gifted to the museum in the decades since its opening. For any well-known artist this would be a fascinating and daunting task; with Warhol, it’s practically insurmountable.

“We say we have about half a million objects,” says Gray, “but there’s no hard count and I’d bet it’s more like three-quarters of a million.”

For a few key decades, just about everything that touched the American cultural landscape passed through Warhol’s gaze. And he kept everything—from plastic doo-dads and pages cut from magazines all the way up to invaluable original Basquiat artworks.

He kept the original master tapes from the Velvet Underground’s Scepter Studio sessions, too. It’s just that, for years, no one knew they were there.

“Warhol was not the most prudent of organizers,” says Gray. “And when he died, they just started boxing everything up and then, years later, dropped it off at our doorstep.”

Since The Warhol’s 1994 opening in Pittsburgh, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts in New York City has made regular donations of Warhol’s possessions, eventually passing on almost everything he left behind. The tapes were in a particularly large donation—truckloads of objects—made a few years ago. The recordings had been in Warhol’s possession for decades, ever since Columbia Records sent them to him with a letter explaining that they were clearing their vaults of inactive tapes and that these two had his name associated with them: no further information; no dates, no names, no identification. That was in 1969.

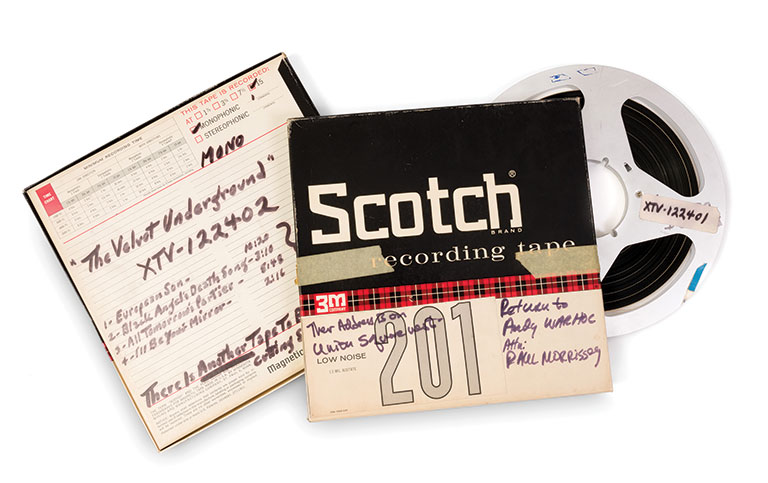

Master Tapes for The Velvet Underground at Scepter Studios, 1966, The Andy Warhol Museum; Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

In 2020, Gray became head of archives at The Warhol and picked up where his predecessor left off. Matt Wrbican was the assistant archivist from before its official opening and became chief archivist in 2011 until his untimely death from cancer at age 60 in 2019. (A towering figure in Warhol studies, Wrbican left a legacy of work based on the archives that includes five books as well as his assistance on countless exhibitions, articles, films, and other projects.) Before his illness, Wrbican had been processing the most recent large Foundation donation, and when Gray picked up the task one object stood out.

“He was spearheading the processing of that donation before he passed away, and he discovered the tapes,” says Gray. But Wrbican hadn’t actually heard them. That had to wait for the tapes to be carefully transferred to a digital format outside the museum. “We have a policy—we don’t play an original tape, just in case it breaks or something happens: that recorded content could be lost forever. But I saw that Matt Wrbican had written, ‘Velvet Underground’— I’m a fan, I have a connection to that music, on a personal level, so I had those tapes digitized so that we could find out what was on them.”

There was a clue as to what Gray had happened upon. On the box was a serial number, which Gray matched to the sole acetate record (a one-off test or demo pressing) of the Scepter recordings—a scratchy document known to fans, released on the album’s 45th-anniversary reissue. Once he heard the music, he knew that’s what he had: a window into a moment in time that still resonates today.

A Sonic Experience

What does it mean to listen to music in a particular place? A place with some relationship, some meaning, to that music?

Classic rock albums, the ones fans have heard hundreds of times, tend towards the rote. They can change over the years from artistic lifeblood to something that feels inevitable—no longer an emotional cry, but a script that fans know by heart.

But a new take on the old script, heard in a novel space and environment, can change all that. For some of those well-versed fans, hearing the newly discovered Scepter recordings in The Andy Warhol Museum will bring out the humanity, the moment, of The Velvet Underground & Nico.

It’s in the little things, like the aspirated sounds in “Black Angel’s Death Song”—the “tshhhhhh!” of John Cale hissing; the “p” in Lou Reed’s “plate”; the “ch” in “choose,” over and over. They’re no longer the rote moments of a classic recording, but the explosive breath of human beings; a snapshot of a unique moment in time.

Harrison insists that these recordings—clean, original master tapes—are not “better” sounding than, say, the popping and crackling of the known acetate. Rather, he says, they have a “different sonic quality.” The goal isn’t clean, digital, headphone-sound perfection, but a new experience of something important to our shared cultural milieu.

“In the exhibition, what we’re not doing is sitting and listening to this on our headphones,” says Harrison. “This music came into being in rehearsals at Warhol’s Factory—he was hearing this on a daily basis at that time. So, in the exhibition, the music is juxtaposed with the films that were being made at the same time. So it all becomes part of the same thing, because that’s the way Warhol heard it—the way he wanted to hear it.”

The exhibition includes photographs by Steve Schapiro of the Velvet Underground at the height of their Downtown cool, some blown up to wall-sized images, plus 37 of Warhol’s Screen Tests of the band members. It includes the music, played throughout the museum’s black-box exhibition space that has been remodeled for the best-possible acoustic response. And it includes related work made at the time of the recordings, such as Warhol’s film of Salvador Dali.

“In the exhibition, what we’re not doing is sitting and listening to this on our headphones. This music came into being in rehearsals at Warhol’s Factory—he was hearing this on a daily basis at that time.”

-Ben Harrison

Warhol’s iconic album cover artwork is represented in obsessive form. Mark Satlof is a New York City record collector who specializes in one thing: copies of The Velvet Underground & Nico, of which he currently possesses around 1,000. For this exhibition, he’s loaned the museum 100 copies in various conditions and states of “peel”—in other words, on some, the banana sticker is untouched; on others, fully peeled off, and everything in between.

Satlof comes by his love of the album honestly: He’s a longtime New Yorker, having moved there in 1982 at the age of 18, whose affection for the city goes all the way to being a licensed tour guide. His fascination with perhaps the most New York album ever made came while listening to Waiting for the Man, with its lyric, “Up to Lexington, 125…”

“One night when I was a sophomore in college, I was in a friend’s dorm suite overlooking Harlem,” says Satlof. “It was very late at night and I heard this record like I never heard it before and I looked down and thought, ‘Oh, there’s Lexington and 125th—it’s right there.’ The switch went in my head. And I have a collector mentality, so—I collected.”

The Velvet Underground, The Velvet Underground & Nico, 1967, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

He hit it big with his first copy: a “full banana” copy (the sticker unpeeled) in great condition and bearing the signature of one Lou Reed. He kept going. After he’d acquired 30 or 40 copies of the album, it occurred to him what he was actually doing.

“This is Andy’s art project,” says Satlof. “In my head, this is what he wanted: It’s a meta artwork. With the exception of copies that are still sealed in plastic, every other copy of this record has been messed up; it’s been interacted with by people. My favorites are the ones that are really beat up—coffee stains, drawings, graffiti on them, the records scratched and dirty and worn. Because someone loved that album. And they loved it in 1967. Today, it’s out there, lyrically and sonically, but in 1967? This was not the Mamas and the Papas.”

There’s little doubt that more surprises are lurking in Warhol’s archives. But what those surprises will be depends not just on the objects, but also on the way our own moment interprets them.

“It’s about perspective,” Gray says. “The objects are amorphous—the way they can be interpreted is full of so many possibilities. We need to see what researchers and curators come up with to determine what’s of the greatest value. Because some things—like these tapes, or an original Warhol painting—they would generate interest on the auction block; that’s the traditional idea of value. I see value as being in finding a deeper connection, and that’s never going to run out.

“This archive will never be exhausted.”

The Velvets

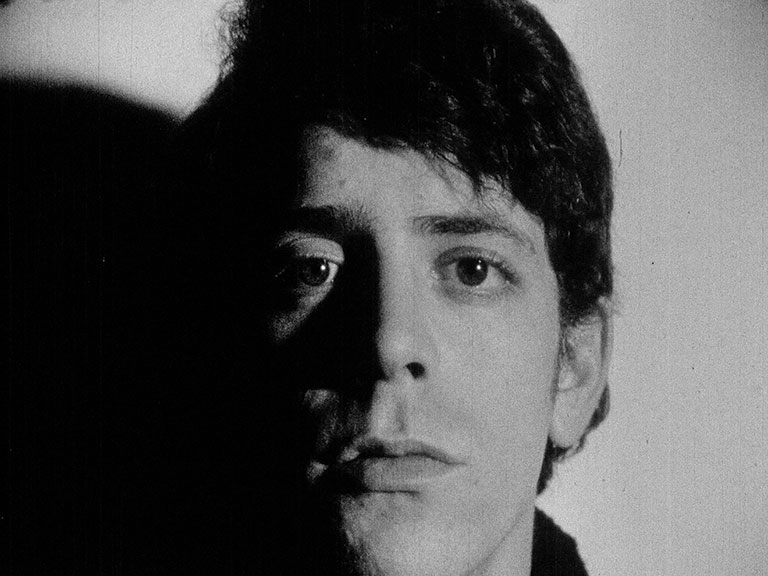

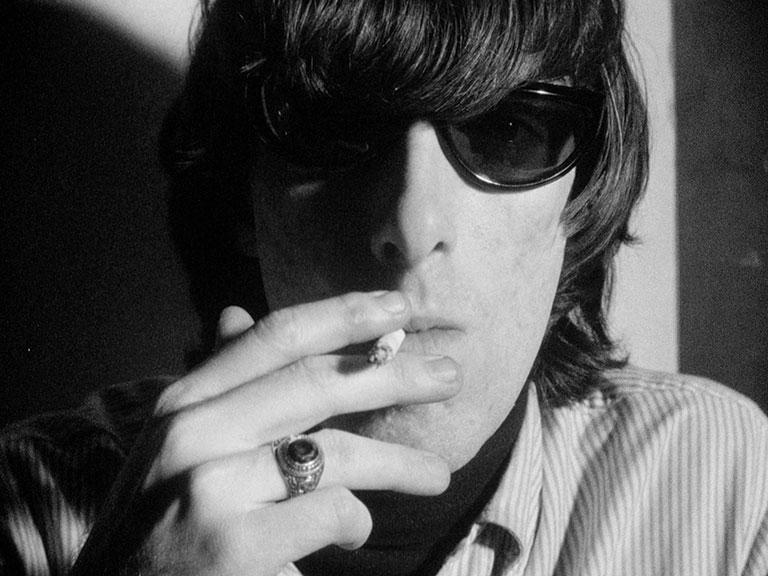

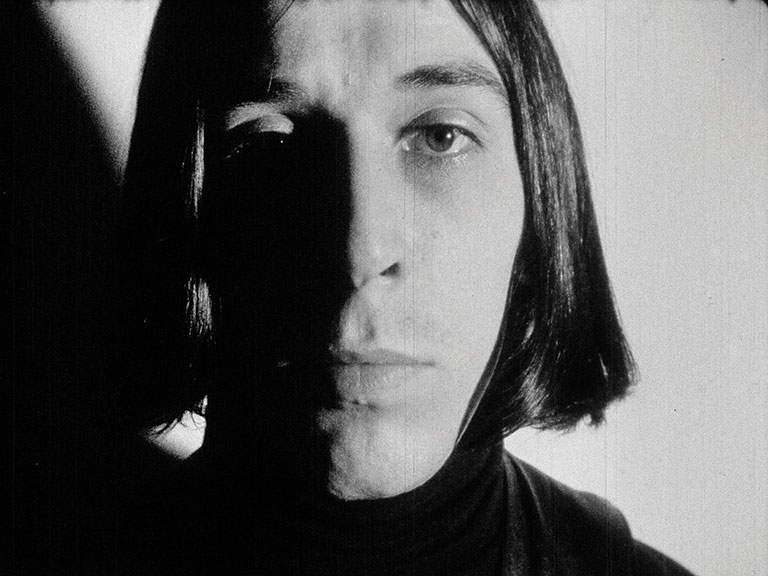

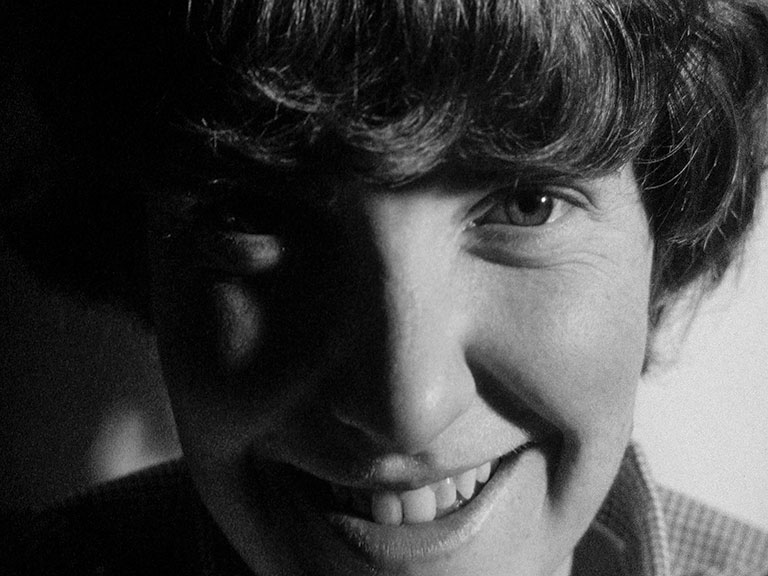

From Top: Andy Warhol, Lou Reed [ST266]; Sterling Morrison (Smoking) [ST225]; Nico [ST240]; John Cale [ST43]; Maureen Tucker [ST344], 1966, © The Andy Warhol Museum. All rights reserved

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up