Editor’s note: This excerpt is from an article in the November 1939 issue of Carnegie magazine that announces the opening of Buhl Planetarium. Once a stand-alone planetarium, the Buhl merged with Carnegie Museums in 1987 and officially became part of Carnegie Science Center upon its opening in 1991.

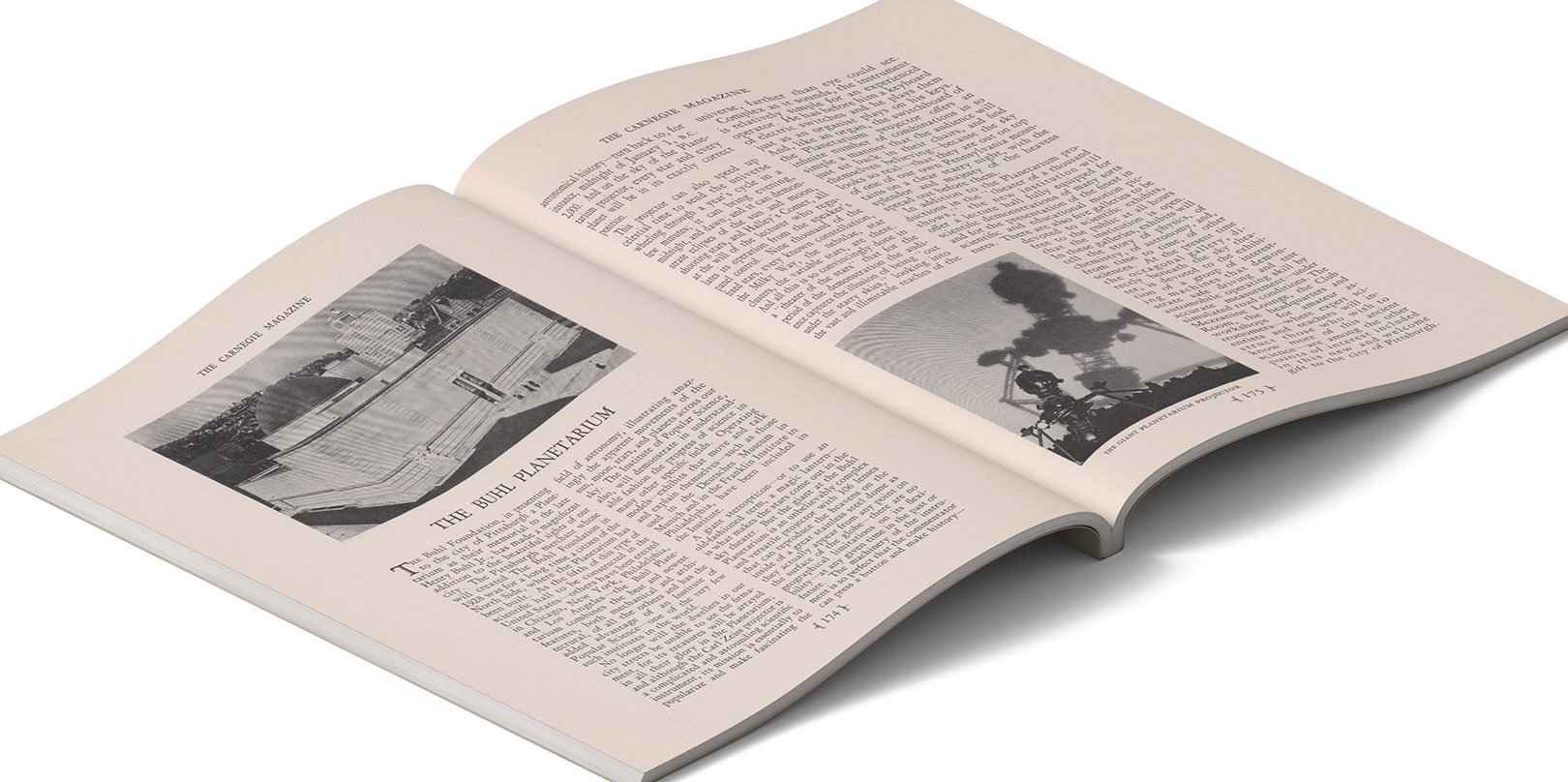

The Buhl Foundation, in presenting to the city of Pittsburgh a Planetarium as their memorial to the late Henry Buhl Jr., has made a magnificent addition to the beautiful sights of our city. The Pittsburgh merchant whose will created The Buhl Foundation in 1928 was for a long time a citizen of the North Side, where the Planetarium has been built. As the fifth of this type of scientific hall to be constructed in the United States—others have been erected in Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles—the Buhl Planetarium combines the best and newest features, both mechanical and architectural, of all the others and has the added advantage of an Institute of Popular Science—one of the very few such institutes in the world.

No longer will the dwellers in our city streets be unable to see the firmament, for its treasures will be arrayed in all their glory in the Planetarium; and although the Carl Zeiss projector is a complicated and astounding scientific instrument, its mission is essentially to popularize and make fascinating the field of astronomy, illustrating amazingly the apparent movements of the sun, moon, stars, and planets across our sky. The Institute of Popular Science, also, will demonstrate in understandable fashion the progress of science in many other specific fields. Operating models—exhibits that move and talk and explain themselves—such as those used in the Deutsches Museum in Munich and in the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, have been included in the Institute.

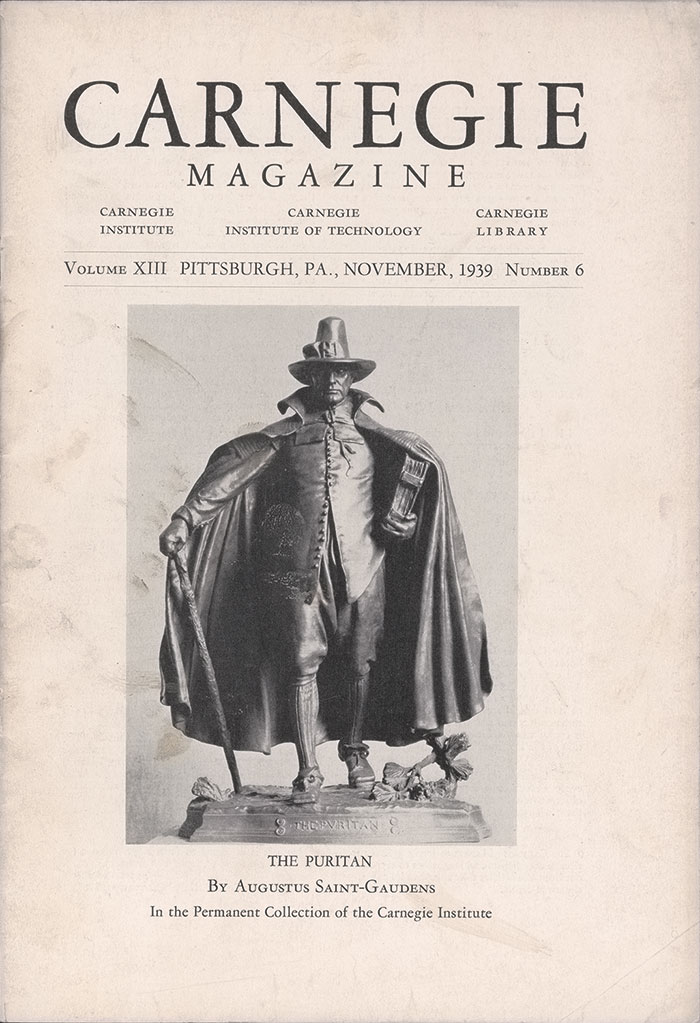

A giant stereopticon—or to use an old-fashioned term, a magic lantern—is what makes the stars come out in the sky theater. But the giant at the Buhl Planetarium is an unbelievably complex and versatile projector with 106 lenses that can reproduce the heavens on the inside of a great stainless steel dome as they actually appear from any point on the surface of the globe—there are no geographical limitations on its flexibility—at any given time in the past or future. The machinery of the instrument is so perfect that the commentator can press a button and make history—astronomical history—turn back to, for instance, midnight of January 1, B.C. 2,000. And on the sky of the Planetarium projector, every star and every planet will be in its exactly correct position.