You May Also Like

Visions for a Better World The Consummate Friend and Volunteer Creating Belonging Through ArtNyjah Cephas’ summer included an ideal Frick Park activity: pulling tree branches down to look for evidence of one of her favorite insects—moths—by way of their bite marks in the leaves.

“It’s just so interesting how much butterflies and moths can tell you about what’s around you because there are certain moths that are specialists, so they only eat a specific plant as caterpillars,” she says. “If you know the moth is there, then you know that the plant is there; and if the plant is there, you can tell what the soil conditions are. It’s just like a little investigation.”

For Cephas, a naturalist educator with the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, nature is both comforting and energizing. It is an environment where, no matter the chaos happening around the world, she seeks refuge. “I know that trees are never gonna judge me,” she says. “I can just be a human and have the trees be the trees.”

As a Black woman, she says being in nature can sometimes feel otherwise. “It doesn’t always feel like others think I should be there,” she says. The idea that being immersed in the outdoors is the realm of white people is so pervasive, she says, that “I often find myself thinking the same thing.”

But Cephas ultimately rejects those notions and understands that she does belong in nature. And in her role as a naturalist educator, she has been working to convince other people—many of them children of color—that they belong, too. Cephas’s experience as an educator helps her engage with others and create a connection through their shared curiosity. “I feel like the more times other people can see people that look like me outside, the more used to it they’ll get, and the more opportunities for me and people like me to just go enjoy ourselves. I just wish it wasn’t that complex.”

Creating An Inclusive Community

Institutions like the American Society of Naturalists and Carnegie Museum of Natural History are making a concerted effort to support diversity initiatives and create a more inclusive community of nature lovers.

Laurie Giarratani, director of learning and community at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, says museums have an important role to play in creating accessibility, within museums themselves as well as in their work out in the community.

Objectivity is important in science, Giarratani says, but we shouldn’t overlook the influence of lived experience on the field. “Fundamentally, science is a cultural practice,” she notes. “It’s a way of conversing about and observing the world and documenting the world—that humans invented. And so we bring our human selves to it, which includes biases and also really unique insights.”

“I feel like the more times other people can see people that look like me outside, the more used to it they’ll get, and the more opportunities for me and people like me to just go enjoy ourselves. I just wish it wasn’t that complex.“

-Nyjah Cephas, naturalist educator with the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy

About the latter, she mentions Akiima Price, who, in her 2018 presentation for the museum’s R.W. Moriarty Science Seminar series, spoke about the role of naturalism in Harriet Tubman’s life. While trapping muskrats as an enslaved child in Maryland, Tubman learned about wildlife, plants, navigation of marshes, and other skills that became fundamental to the success of the Underground Railroad.

“That was the kind of example where you start kind of broadening your perspective on who is a naturalist or how somebody’s knowledge of nature played this really important role in American history,” Giarratani says.

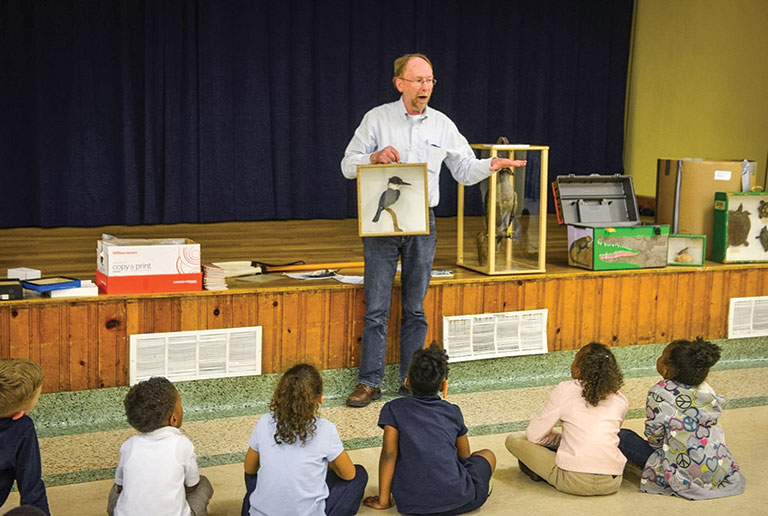

She sees the museum’s Educator Loan Collection as a unique way to give children from all over Pittsburgh access to a hands-on way to learn about nature.

For over 30 years, Pat McShea, program officer for the collection, has curated themed kits—portable plastic toolboxes containing gems, animal skulls, and other museum specimens—that educators can take out on loan. The collection is the Museum of Natural History’s longest-running educational program, dating back to its first director, William Jacob Holland. The kits contain specimens that don’t have the quality or scientific importance to be part of the museum’s permanent collection but are perfect for hands-on learning for children. McShea’s hope is that these items give kids a “wow!” experience. They help children experience things they’ll likely never run across on their own—a whale spine—or better understand something in their literal backyard—the thousands of crows that roost each winter in the Hill District.

After hearing Price’s talk, McShea continued his own learning on the subject and added Tubman’s story to an existing muskrat loan kit. The combination serves as a tangible illustration as to how inextricably linked nature and human history are.

In 2017, McShea began to create kits aimed at reaching early-career Black naturalists. This came out of a meeting several years earlier with Will Tolliver Jr., a naturalist educational consultant who was working at the Parks Conservancy at the time. The two shared an immediate bond over their alma mater, Allegheny College, and Tolliver’s Homewood neighborhood, where McShea’s father grew up; the relationship blossomed from there.

Connecting With Black Naturalists

“What’s interesting about being marginalized in the woods is it’s really no different than being marginalized anywhere else, which is unfortunate, right?” says Tolliver, now associate director for audience engagement with PBS. He brings up the viral video in 2020 taken by Black birder Christian Cooper in Central Park. In it, Cooper asks a white woman to put a leash on her dog, and she responds by calling the police and emphasizing Cooper’s race. The video led to a national discussion about racism as it relates to outdoor spaces.

“I think the media makes us hear more about the [prejudice around] people not belonging in places, but whenever you don’t have to worry about that, it’s really great,” he says.

Like Cephas, Tolliver enjoys exploring local parks on his own. He’s drawn to streams, looking for salamanders and other macroinvertebrates, as well as “the art that nature produces” in the form of lichen. He also likes the peace of sitting on a log to “soak in the moment.”

“Fundamentally, science is a cultural practice. It’s a way of conversing about and observing the world and documenting the world—that humans invented. And so we bring our human selves to it, which includes biases and also really unique insights.”

Laurie Giarratani, Director of Learning and Community at Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Thinking about macroinvertebrates leads to thinking about ecosystems, which brings out Tolliver’s inner philosopher, since a healthy ecosystem is a biodiverse ecosystem. That idea “eventually made me really interested in equity, diversity, and inclusion,” he says. “If you don’t have biodiversity in your stream, if you don’t have diversity in your workplace, in your life, you’re not getting a full aspect of what a healthy world ecosystem looks like.”

The beginning of his career was focused especially on connecting with families and kids of color, and McShea wanted to do what he could to support Tolliver’s work.

The museum’s Tolliver-inspired kit is designed to teach about regional species and includes feathers, a red-tailed hawk wing and tail, dried snakeskin in a cocoa container, a deer antler, turtle shells, a few pelts (including raccoon), and skulls aplenty (birds, muskrat, deer).

“This thing has gotten me through so many times,” Tolliver says. He’s used it for groups large and small, with younger kids—ages 3 to 8 is his favorite demographic—as well as college students and families. “Part of me never wants to let it go.”

Through the consulting practice he started in 2020, Tolliver offers virtual programming, neighborhood walks, and exploration in Pittsburgh’s parks. “I really model for them how to be curious about the environment, good stewards of the world around them, and understanding their place and connection to the world,” he says. He especially loves those “‘aha!’ moments, like when their eyes light up and they get something. That, to me, is the magic of the world.”

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua FranzosAs he began collaborating with Tolliver, McShea also took part in the museum’s 21st Century Naturalist initiative born out of the realization that scientists needed to take a holistic approach to addressing modern issues like climate change and biodiversity loss. And that includes building a more diverse community of naturalists in the Pittsburgh region.

“If you don’t have biodiversity in your stream, if you don’t have diversity in your workplace, in your life, you’re not getting a full aspect of what a healthy world ecosystem looks like.”

Will Tolliver Jr., a naturalist educational consultant

“There would be Black naturalists without our efforts, but we’re just trying to make it easier, maybe more rapid or bigger, or whatever we’re able to do to foster growth in the numbers,” McShea says.

Giarratani notes that, through McShea’s work, he cultivates strong relationships with a diverse group of educators who are using the kits. “Each of those adults is connected to young people and has built trust with them. These are connections the museum could not make alone.”

Welcoming The Next Generation

Cephas has been teaching teenagers through the Parks Conservancy’s different educational programs since 2018. She first arrived at the organization years ago as a high school student, first for an invasive removal project and then for a summer internship and her high school senior project. Her work now brings her inside classrooms around the city, where she’s able to reach a variety of students, rather than just those who are able to self-select for activities such as summer camps.

“Everybody on the [Conservancy] staff is just really invested in making life and education more equitable,” she says. That can be “as simple as starting off the program by saying, ‘Hey, everybody’s at a different place in how comfortable they are out here. You’re good as you are.’”

Cephas is fascinated by how the link between nature and human history plays out in Pittsburgh. She mentions how the city’s industrial and labor histories are reflected in the neighborhoods that workers and industries built, and how that affected humans and the natural environment.

Cephas grew up down the street from Hunter Park in Wilkinsburg; though there are basketball courts, a picnic area, and other amenities, she noticed that it wasn’t being embraced by local residents. She says learning the history of the park was a matter of applying her investigative skills: Her dad shared how there used to be a lot of violence there, followed by it becoming a dumping ground, which led to disengagement from the community.

“Without talking to my dad, I wouldn’t have understood that, and that’s an important story to be heard—and changed.” Cephas wants to be part of the change by building bridges between people and the natural world.

In meeting with young people, Cephas serves as a kind of real-life model for a more diverse younger generation of naturalists. She’s found that the best method for engaging her students is to “try my best to be authentic about who I am and why I’m excited.”

That excitement can be contagious. One group, for instance, had the combined experience of seeing a screech owl in Frick Park and then getting a closer look through one of the museum’s toolboxes. The kit had items like owl bones and an owl pellet for Cephas’s students to examine.

By reaching out to adults to hear about a neighborhood’s story, and by encouraging teenagers to feel excited about what they might find together in Frick Park, all Cephas really wants, in the end, is for everybody to have access to nature and the peace of mind they can get from not feeling judged. At a minimum, she wants them to feel safe.

“Nature is all around them all the time, so everybody has experience with it in some way,” she says. “I think it’s a matter of saying, ‘Hey, your experience has value, and you’re allowed to understand the world around you more in whatever way works best for you. And I’m here to support you through that.’”

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up