You May Also Like

Visions for a Better World The Consummate Friend and Volunteer Creating Belonging Through ArtA black telephone bench stood in the middle of the long hallway that ran from the front door to the kitchen of the second-floor apartment at 2519 Webster Avenue in the Hill District. Next to the bench sat a lamp, casting its glow over a flip-top notepad. It was the home office, of sorts, where suffragist Daisy Lampkin would work, dressed to the nines, phone cradled against her ear.

“I’d be playing with my toys in the living room, and I’d hear her saying, ‘Yes, Roy, dear,’ or ‘Yes, Thurgood, darling, there’s something I need you to do,’” recalls her grandson Earl Childs, who lived one floor above with his parents. “She had such a soft and endearing voice. It wasn’t until much later in life that I realized she was talking to important men like [civil rights leader] Roy Wilkins or [Supreme Court Justice] Thurgood Marshall on that phone. Of course, I was so young that I had no concept of her being ‘Daisy Lampkin.’ To me, she was just grandma; my best buddy and playmate.”

Born on August 9, 1883, in Reading, Pennsylvania, Daisy Elizabeth Adams moved to Pittsburgh in 1909, and married William Lampkin three years later. It was the height of the women’s suffrage movement, and Daisy became a passionate advocate for the rights of all Black Americans, particularly those of Black women, and her impromptu speeches on the sidewalks around the Hill stopped people in their tracks.

“She was such a lovely force of nature,” recalls Charlene Foggie-Barnett, community archivist for the Teenie Harris Archive at Carnegie Museum of Art and a Hill District native who was a childhood friend of Childs’. “I think of her from the perspective of being a ‘shero’ of not only Black Pittsburgh but all girls and women of color. It’s women like her that made it possible for us to vote, have certain jobs, and to be in the room.”

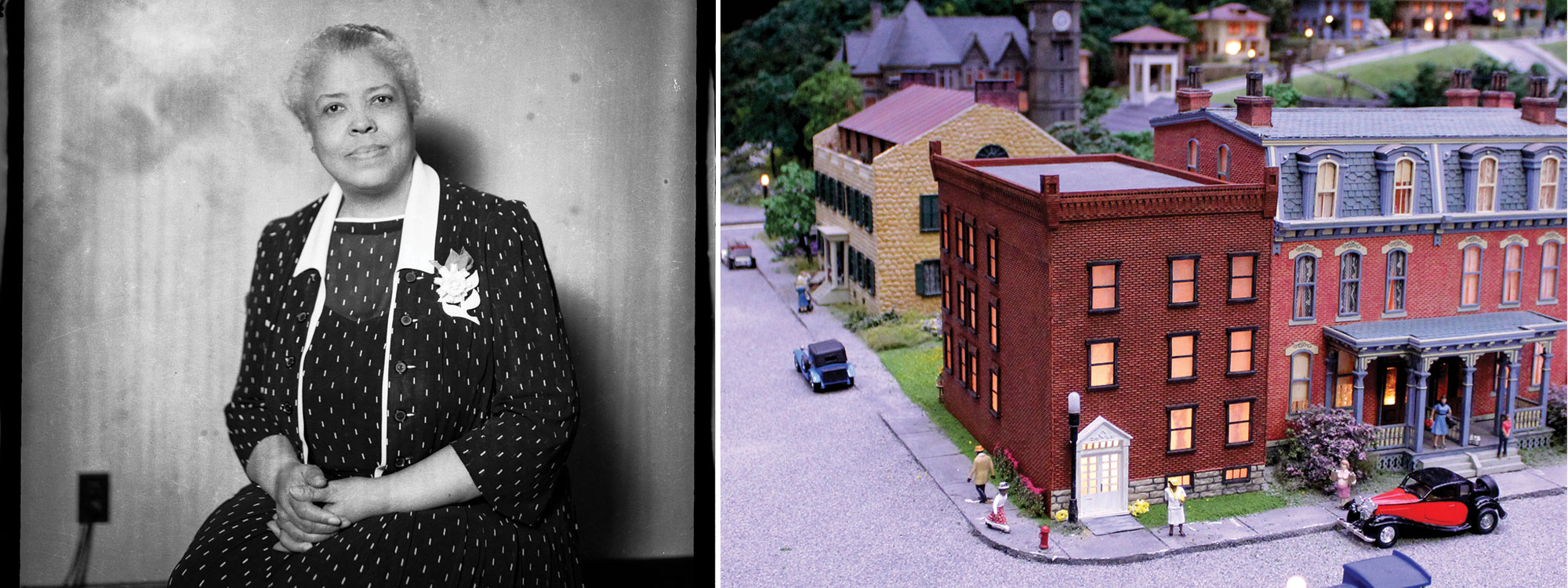

Late last year, the staff of Carnegie Science Center added a tiny likeness of Lampkin to its popular Miniature Railroad & Village®. Standing outside a replica of the three-story, red brick apartment building that she and her husband owned and called home on Webster Avenue, she’s wearing a yellow and white dress—colors favored by suffragists—with a matching hat, her signature accessory.

“We were looking for a way to represent the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage and the 19th amendment,” says Patty Everly, the Science Center’s curator of historic exhibits. “We wanted 2020 to be the year of the woman, and Daisy was the perfect fit.”

By 1915, Lampkin had gained notoriety for the suffragist meetings she held in her home, which were springboards to leadership positions both locally and nationally, including in the National Association of Colored Women, Negro Voters League of Pennsylvania, and Colored Voters Division of the Republican National Committee. After spearheading an effort to boost subscriptions for the floundering Pittsburgh Courier, she became vice president and part owner. She blazed the way for female leadership, establishing the first Red Cross chapter among Black women and local chapters of the Urban League and the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Pittsburgh.

“Both Thurgood Marshall and Roy Wilkins called her ‘Aunt Daisy.’ She was a genteel lady and was charming. A steel hammer in a velvet glove.”

– Earl Childs on his grandmother, Daisy Lampkin

In 1924, she was invited to the White House to meet with President Calvin Coolidge, the only woman in a roomful of men discussing racial discrimination. In 1930, the NAACP’s executive secretary, Walter White, recruited Daisy as the group’s first field secretary, and not long after, she became its national field secretary.

“She didn’t deal with these men in a rough and tough way,” says Childs, a local dentist. “Both Thurgood Marshall and Roy Wilkins called her ‘Aunt Daisy.’ She was a genteel lady and was charming. A steel hammer in a velvet glove.”

Still, her persona never consumed her. She doted on her only grandchild, whom she affectionately called “Little Earl.”

“At the time, there were very few Black students who attended Falk School, and, at first, they didn’t want to let me in,” Childs recalls. “Supposedly, grandma went to the school. Keep in mind, at that point, she was ‘Daisy Lampkin.’ Soon, I was attending junior kindergarten there. There were no marches. She didn’t have to make a big stink about things. She just enforced what was right and fair.”

Lampkin suffered a stroke while attending a NAACP meeting in Camden, New Jersey, and died on March 10, 1965, at age 81. A Pennsylvania state historical marker stands outside her former home on Webster Avenue, which Childs now owns.

Of being immortalized in a historic exhibit that appeals to all ages, Childs believes his grandmother would be very proud. “She would say, ‘Well, that’s very nice, thank you so much,’ and then she’d get back to work.”

Above: Charles “Teenie” Harris, Portrait of Daisy Lampkin, posed possibly in Harris Studio, c. 1940-1960, Carnegie Museum of Art; Heinz Family Fund

Receive more stories in your email

Sign up