“All forces of nature are interlaced and interwoven. The earth is one great, living organism where everything is connected.” – Alexander von Humboldt

Tucked away in an unassuming office near Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s world-renowned bird collection, Steve Rogers leads a group of visitors to a long row of specimen cabinets and pulls open a drawer filled with some of the museum’s most precious residents. Inside, 16 dark brown-and-white Dusky Seaside Sparrows are at rest, belly up.

Rogers, who has some 195,000 birds in his care as collection manager, paints a picture of what life was like for these petite songbirds that once made their home in a 10-mile stretch along Florida’s eastern coastal marshes. That is, until NASA set up shop in nearby Cape Canaveral, causing a domino effect in land development. The animal’s demise began in the 1950s, he notes, when DDT was sprayed and the area was flooded to reduce mosquitoes around the Kennedy Space Center, and nearby marshes were drained to make way for highway development.

Because the sparrows didn’t migrate, they were particularly vulnerable to change. On June 16, 1987—less than 20 years after the birds numbered about 1,800—the last Dusky Seaside Sparrow died in captivity at Walt Disney World, becoming another example of human-caused extinction, like the dodo and passenger pigeon before it. The museum’s sparrows, markers of the unintended consequences of human progress, were all collected or donated by 1910, when the subspecies was still plentiful.

This cautionary tale is just one of many in the museum’s vast collections teeming with the life and death dramas of the natural world. Tagging along with Rogers as curious fact finders this day is artist and Carnegie Mellon University professor Richard Pell, along with 10 of his undergraduate art students charged with thinking about natural history collections in non-traditional ways.

Having arrived at the museum in search of evidence of the Anthropocene—Earth in the age of humanity—the students are suddenly face to feather with one of its loudest alarm bells: the extinction crisis.

According to the 2016 Living Planet Index, a report from the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London released in late October, since 1970 the planet has experienced a staggering loss of life, including a 58 percent drop in the number of vertebrates (fish, mammals, birds, and reptiles). The same report predicts that two-thirds of all wildlife could be lost by 2020, based on 1970 population levels.

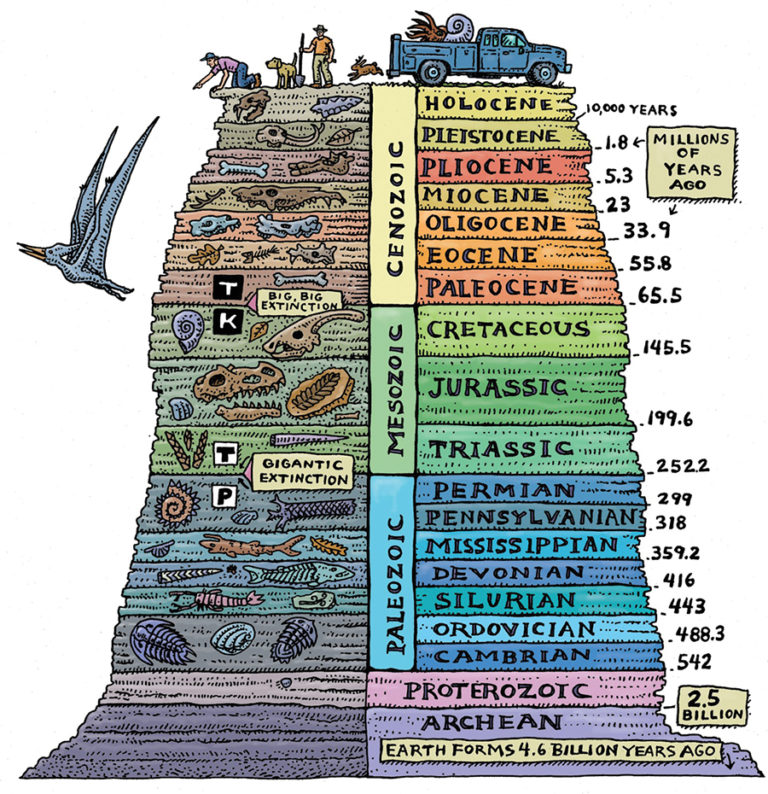

This startling extinction rate is more than 100 times its natural level—and that’s only taking into account the animals we know about. In the last half-billion years, life on Earth has been nearly wiped out five times—by things such as climate change, volcanoes, the ice age, and the asteroid that decimated the dinosaurs and a whole slew of other species.

Now, many signs point to the fact that not only have we entered a sixth mass extinction, but we alone have caused it—through the sum effect of deforestation, overfishing, the spread of invasive species, pollution, rapid climate change, and the list goes on.

“The story of the sparrow is so recent, you can actually put yourself there,” says Pell. “The Anthropocene is not about necessarily having a funeral, but taking a cold hard look at ‘What is our impact?’”

Written in Stone

The idea that humankind’s influence on the planet is so profound that it’s becoming irreversible has a history dating back to the 1870s. But the word Anthropocene wasn’t coined until about 130 years later by Dutch chemist Paul Crutzen, who in the 1970s and ’80s made major discoveries about the relationship between the ozone layer and the planet’s health, earning him a Nobel Prize. In 2000, he nearly blurted out the word Anthropocene at a scientific conference as he boldly pronounced that the most recent chapter in Earth’s history, the Holocene, which stretched back nearly 12,000 years to the end of the last ice age, was in fact over, giving way to a new era of the human.

Two years later, Crutzen and a colleague published their notion of the Anthropocene in the journal Nature, and it’s since been widely adopted across disciplines—embraced by artists and environmentalists alike as an important cultural period, not unlike the Renaissance or Medieval eras.

Much to the satisfaction of Eric Dorfman, director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the Anthropocene is also being formally considered as a new geological era. In August, an international working group of 35 scientists gave it the green light, citing overwhelming evidence. Now, the world waits on the determination of the Union of Geological Sciences, the organization that oversees the process geologists use to carve up Earth’s 4.5 billion years of history into digestible chapters. This geological timescale isn’t easily changed. It’s an inherently conservative process, and with good reason: the scaffolding of deep time has taken centuries to erect.

The geological history of Earth. We are currently in the Holocene, but activity by humans has pushed us into the Anthropocene, many scientists say.

The holistic approach to the study of the Anthropocene has already inspired the new guiding vision for Carnegie Museum of Natural History. The museum’s focus, says Dorfman, is on “the unity and interdependence of humans and nature” and a call for stewardship of the Earth. As part of a family of two art and two science museums, the Museum of Natural History is uniquely positioned to not only embrace the young and urgent science of the Anthropocene in a comprehensive way, but to help lead the field, says Dorfman. The plan is to investigate nature and humankind’s intimate relationship not just with scientific methods but also through art—reaching audiences “in both the heart and the mind,” he adds.

“The Anthropocene is very useful in getting us to think cohesively about what we’re doing to the planet, because things like climate change, pollution, population growth, biodiversity loss—these issues are integrated,” Dorfman says. “There’s a whole lot of work that a focus on the Anthropocene does for us, and we can weave that story throughout the entire museum, using technology to unpack it. If we’re going to make an impact on people, it’s going to be through emotion as well as knowledge.”

While the evidence of the human impact on the planet is abundant, the changes are very recent in geological terms, where an era usually spans tens of millions of years. “One criticism of the Anthropocene as geology is that it is very short,” says Jan Zalasiewicz, a geologist at the University of Leicester and chair of the Working Group on the Anthropocene. “Our response is that many of the changes are irreversible.”

But not everyone agrees with Zalasiewicz’s assessment, including some of his fellow geologists. The detractors acknowledge that humans are in fact permanently altering the planet, but they’re not convinced that the geological record reflects it—yet.

Stratigraphers piece together Earth’s history from clues left in layers of rocks millions of years after the fact. To define a new era, a worldwide signature must be found in the Earth’s sediments. That’s why researchers set the birth of the Anthropocene around 1950, when radioactive fallout from nuclear bomb testing began leaving a distinct layer in the geological record.

“But we are spoiled for choice,” says Zalasiewicz, noting that, at about the same time, humans were also leaving their mark through millions of tons of plastic, carbon pollution from power plants, and the rise of the concrete cities. Each is likely to leave its own fossil record in stone.

“There has to be a balance between the messages that we give and the good that we do,” says Dorfman. “We could sit for years deciding on whether we have the perfect data set while the planet descends into chaos, and then the quality of our data won’t matter.”

A Wicked Problem

While delivering a recent lecture on the Anthropocene, Steve Tonsor, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s director of science and research, outlined some of its mounting evidence.

“In every place we look around the earth, we see the evidence of human effects,” says Tonsor. “From outer space, one can see the 7 billion humans at night lighting up the earth. In the day, we can see that the landscapes of the earth have been profoundly changed.”

While humans have only been around for about 200,000 years—less than .01 percent of Earth’s timeline—in that short blip we’ve altered more than 50 percent of Earth’s land by clearing fields, building cities, damning rivers, and removing mountaintops in search of coal. If we look only at ice-free land, notes Tonsor, the estimate climbs to 83 percent.

Through mining activities alone, humans move more sediment than all of the world’s rivers combined. Forests are shrinking at an unsettling rate; there are half as many trees in our forests today as there were when we arrived. And even if humans stopped generating carbon dioxide cold turkey, what we’ve already released through concrete production, deforestation, and the burning of fossil fuels would last tens of thousands of years, continuing to warm the planet and change the chemical makeup of its oceans.

“In every place we look around the earth, we see the evidence of human effects. From outer space, one can see the 7 billion humans at night lighting up the earth. In the day, we can see that the landscapes of the earth have been profoundly changed.”

– Steve Tonsor, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Director of Science and Research

Evidence of the Anthropocene: radioactive elements dispersed across Earth by nuclear bomb tests, the bones of the domestic chicken—now a global staple—and plastic pollution.

All of these challenges are, of course, heightened by an ever-growing human population, which has more than doubled in the last 50 years. By 2012, the equivalent of 1.6 Earths were needed to provide the resources and services we consume each year.

“We’ve entered the Anthropocene and it’s not looking like heaven on Earth. But I’m not here to depress you, actually,” Tonsor tells the crowd, with a laugh. “I’m here to talk about what we can do. The science makes clear predictions. So, why haven’t we taken action? How can science solve these problems?” he asks. “Well, the bad news is, it cannot.”

That’s because they’re not strictly scientific problems, says Tonsor, but rather a “wicked problem” in which, because of the complex interconnectedness of the Earth’s living, atmospheric, and ocean systems, any potential solutions have both positive and negative consequences. The problem is made more difficult by the way in which western knowledge is structured, a structure that divides up knowledge among disciplines and loses track of nature’s interconnectivity.

“To bring people to the point where they’re able to see what’s happening in the Anthropocene and act on it we have to use all the ways of thinking, all the ways of knowing we can find,” Tonsor says. “What better place to do that than Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, where art and science are joined at the hip, and two world-class universities are in conversation with us as well?”

Taking a page from the early study of natural history, where great thinkers like Alexander von Humboldt and Charles Darwin identified as natural philosophers and practiced as both artists and scientists, Tonsor believes life in the Anthropocene requires reintegration across disciplines. “As scientists, we’re looking at the geology and the atmosphere,” he says. “But the same kinds of gigantically transformative things are going on in terms of cultural change worldwide, technological change, population stresses, and all of these things show up in economics, they show up in poetry, in music, in philosophy.”

As the museum recruits future scientists, he notes, they’ll be looking for those who excel not just in their respective disciplines but who understand how science informs other fields, and vice versa.

While the museum’s leadership team lays the groundwork for a future permanent gallery dedicated to the Anthropocene, it’s also using the concept as the basis for new and multidisciplinary research, as well as a major topic for visitor engagement through temporary exhibits and programming.

Tonsor notes that two ongoing projects are already helping the museum deliver an all-important message of hope in the Anthropocene: the Window Strike Project, a research effort at Powdermill Nature Reserve that assists glass companies in testing product designs that could help prevent millions of birds from perishing each year after flying into glass windows; and the museum’s leadership role in Pittsburgh’s Climate & Urban Systems Partnership (CUSP), a network of informal educators working across the city to spur conversation about ways to curb climate change on the local level.

“So much of the climate change denial comes from the inability to cope with the magnitude of the challenges we face,” Tonsor says. “It’s also important to know large things can happen with small actions by lots of people. That’s how we got into trouble—a whole bunch of people leaving lights on and driving when they didn’t need to. The same kind of accumulation of small actions can also lead to good outcomes. The CUSP program, for instance, is aimed at people understanding how they can help on the scale of their own neighborhood. We plan to do a lot more of this kind of work.”

In early 2017, Carnegie Museums will take the Anthropocene message to a broad audience when it premieres a four-month-long series of eclectic performances, films, and lively discussions, dubbed Strange Times: Earth in the Age of the Human. The series is bringing together scientists and writers, musicians and visual artists to respond to the question: Will we survive ourselves? It’s the first offering of Carnegie Nexus, Carnegie Museums’ new interdisciplinary initiative dedicated to exploring pressing contemporary issues. Strange Times pairs the humanities with the sciences—robotics with philosophers, artists with herpetologists.

“This series is helping us chart our path across disciplines—within Carnegie Museums and across the world, really,” says Tonsor.

Mining the Museum

In October 2017, the Museum of Natural History will debut its first temporary exhibit on the Anthropocene, We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene, which will draw on the museum’s collections to blend the 16th-century concept of the cabinet of curiosities with an examination of what might be humanity’s future.

“Virtually every spot on the planet has now been explored by someone,” says Dorfman. “The exploration is now about our changing world. What we might find in it is as mysterious as an unknown geographical destination.”

It was as part of the museum’s own deep dive into its collections in search of evidence of the Anthropocene—a fairly new and evolving task for many natural history museums—that Tonsor invited Richard Pell and his students to join its efforts by looking at the collections through the eyes of artists and technologists.

As founder of Pittsburgh’s Center for PostNatural History, Pell and his students are especially interested in finding specimens altered by people, an area often ignored by natural history museums. Their search is for domesticated animals that for whatever reason—food, research, productivity, aesthetics—have been modified by humans to fit their needs.

Pell’s class is called “Mining the Museum,” named for a well-known exhibition by African-American artist Fred Wilson that introduced the idea of looking at a museum collection as a cultural work that can be pulled apart and reconfigured, reinterpreted.

As an artist interested in spaces where technology and culture collide, Pell recently spent several months studying the Smithsonian’s natural history collections in search of evidence of the Anthropocene. By examining its rodent collections, he was able to basically map out the development and testing of the atomic bomb, something truly unique to a collection in the United States, especially one with such a close relationship with government. “Typically, collections are looked at as chronicling ecology or evolution or habitat,” says Pell. “When I look at collections, I pay close attention to instances where cultural history and nature might bump into each other.”

He’s not quite sure yet what he might stumble upon in the Carnegie Museums collections, but he notes that his perspective as an artist can be valuable. While scientists need to be incredibly focused and specific, Pell takes a wide view, “looking for things that are outside the focused light.”

He describes the collections as snapshots in time. “It’s like trying to recreate a place based on someone’s vacation pictures, with lots of random moments. We need to tell more complicated stories in museums. We humans have been part of the story all along, just on the other side of the camera.”

Not coincidentally, the opening of the Museum of Natural History’s We Are Nature exhibit will overlap with the annual conference of the International Council of Museums’ Committee for Museums and Collections of Natural History (ICOM NATHIST), which is being hosted by Carnegie Museum of Natural History in the fall of 2017. It’s the first time the conference will be held in the United States, and attendees will include staff from some 300 international peer institutions.

As president of the organization, Dorfman is thrilled to be hosting the group’s next gathering, which will be themed, The Anthropocene: Natural History Museums in the Age of Humanity, a topic that he says couldn’t be more relevant to the work of natural history museums worldwide.

For a short window of time, attendees and the public will get the rare opportunity to view the world’s only mummified head and foot of a dodo—an evocative symbol of human-caused extinction—on loan from the Natural History Museum of the University of Oxford. Also on loan for Cabinets of Change will be Andy Warhol’s Endangered Species series, a set of 10 colorful screenprints portraying endangered animals from around the world. “It will add a very different perspective on what the Anthropocene means and how it manifests,” notes Dorfman.

“As trusted sources, museums have an important role to play,” adds Tonsor. “We need to be effective communicators and conveners. We must be a safe place for unsafe conversations.”