In 1947, a logger named Joseph Cox made a discovery that would not only make him rich but would end up changing the world. And he did it by watching beetles.

You see, up until this point, most chainsaws worked by scratching sharpened edges, like tiny knives, against a piece of wood. And while that method worked alright, the blades had to be honed constantly, and they lost efficiency at high speeds. As someone who often had to sharpen those blades as part of a logging outfit, Cox was always thinking about how to improve this process.

So, one day, while he was searching for salvageable lumber left behind by a series of forest fires in Oregon, Cox happened upon a charred stump infested with “woodworms.” Actually the larvae of a longhorn beetle, the creatures had gnawed through the wood at an incredible clip, piling up sawdust in their wake. Upon closer inspection, Cox observed how it all worked—the left and the right sides of the beetles’ C-shaped jaws took turns not scratching but scooping tiny chips off of the stump.

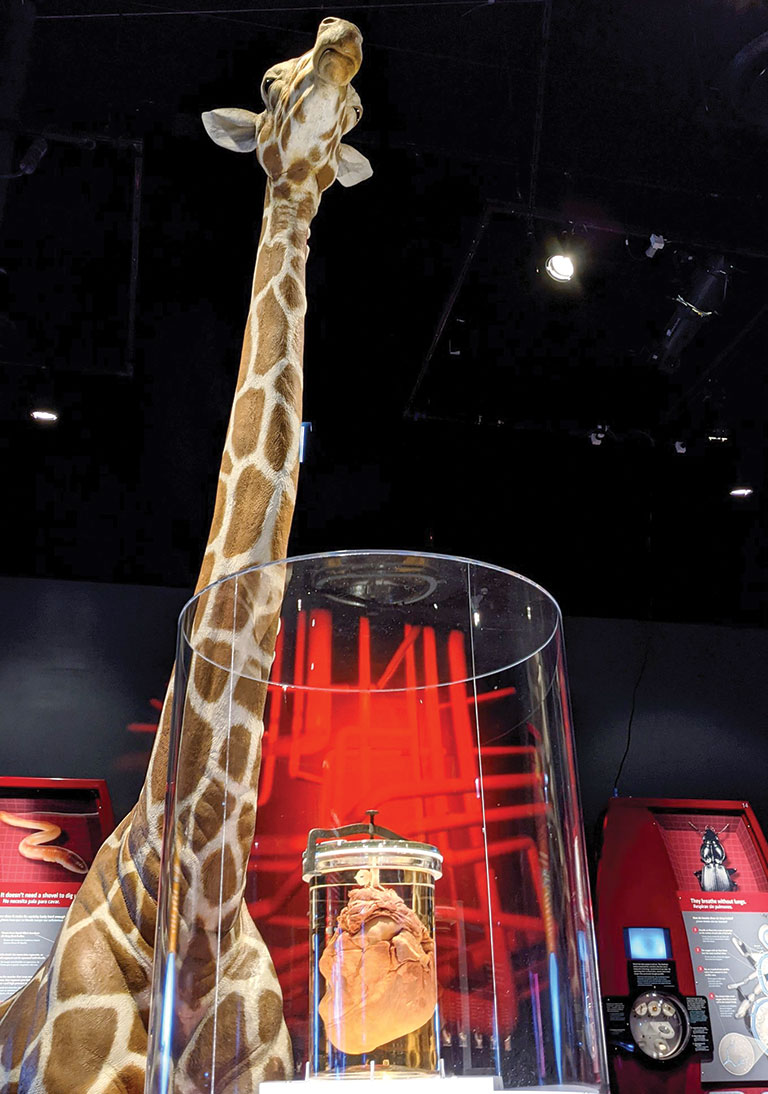

A giraffe’s heart is no bigger than you’d expect for a large animal, but it is unusually powerful and uniquely positioned so it can pump blood up the giraffe’s long neck to the brain.

Intrigued, Cox set to work trying to create a saw blade that mimicked the beetle’s mouth, and in 1950 he earned a patent for his efforts. The new design revolutionized the industry. Go to the hardware store today, and Cox’s beetle-inspired blade is now the chainsaw standard. Few people realize they have timber worms to thank for their bed frames, kitchen cabinets, and baseball bats.

This is just one example of the mechanical marvels found in nature. But there are many, many more, as a new traveling exhibit called Nature’s Amazing Machines makes abundantly clear.

From the heart of a giraffe, which is lopsided so it can create extra pressure for pumping blood all the way up the animal’s elongated neck, to the flexible, spring-like spine of a cheetah that contributes to its top speed of 60 miles per hour, the exhibit shows visitors how physics, biology, and ecology come together to help animals run, fly, swim, burrow, and bite.

The cheetah’s entire body is built for speed.

With digestible chunks of information and hands-on stations that let visitors interact with the exhibit—“Compare your grip strength against that of a chimpanzee!” “Control the epic chomping power of an extinct Dunkleosteus !”—Nature’s Amazing Machines is a perfect cross-section of many of the interesting research areas spread out across Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

“If you look at our current halls, we have a bird hall, a place for bugs, and a section where we’re talking about dinosaurs, but they’re all kind of separated,” says Sarah Crawford, the museum’s director of exhibitions. “What this exhibition does really beautifully is it brings all of these different scientists and their research together in one place. And I think those are the kinds of stories we want to tell.”

The Institute of Beetle Technology

While the exhibit brings in examples from across the plant and animal kingdoms, you could probably fill a museum with these kinds of stories using only beetles.

“There’s nothing humans have invented that a beetle isn’t already doing out there somewhere,” says Ainsley Seago, associate curator of invertebrate zoology. “I like to think of it as the Institute of Beetle Technology.”

For starters, says Seago, the beetle mouthparts that inspired saw blades aren’t just interesting because of their shape. They have chemical secrets, too.

“A lot of beetles that have a wood-boring lifestyle tend to sequester metals in their mandibles,” she says. This gives the insects extra durability because their jaws are literally made out of metal.

Interestingly, beetles and other arthropods don’t even need metal to be strong. That’s because they’ve got exoskeletons made of a translucent polymer called chitin.

“It’s comparable in structure and flexibility to the keratin in our fingernails,” says Seago.

There’s nothing humans have invented that a beetle isn’t already doing out there somewhere. I like to think of it as the Institute of Beetle Technology. – Ainsley Seago, associate curator of Invertebrate Zoology

In extreme cases, creatures like the ironclad beetle build up so many layers of chitin, and sandwich them together in such an interlocking pattern, that you can run the things over with a truck and still not crush them, Seago explains. Humans have adapted the same structural pattern to create very strong but lightweight panels for aircraft construction.

Elsewhere in beetle-dom, darkling beetles harvest water from the air, ladybug beetles fold their wings up like origami, and dung beetles navigate by the light of the stars.

Scientists have even used these animals to learn about light-scattering properties. This is because many beetle species derive their brilliant colors not from pigment but from microscopic structures, like photonic crystals, hidden in their exoskeletons, says Seago. These nanostructures are capable of scattering light in ways more advanced than scientists have been able to achieve in the lab and may pave the way for ultrafast optical computers.

Millions of years before Homo sapiens existed, beetles evolved the ability to create light—lightning bugs!—and defend themselves with tiny, controlled explosions—bombardier beetles!

Each is possible because of special chambers on the beetles’ backsides that control chemical reactions. In the firefly’s case, the beetles mix chemicals together that allow them to glow, which is used for communication and courtship. Likewise, the bombardier’s reaction is defensive, as it creates a hot, foul-tasting sizzle that deters frogs, lizards, and other arthropods from taking a bite.

And if you’re wondering why the beetles don’t blow themselves apart, Seago says it’s because they’ve evolved an ingenious one-way valve.

“So, the chemicals can’t go back where they came from, they can only go out,” she says. “And that allows them to direct their blasts in this sort of machine-gun-like fire.”

Taking Wing

People often say that they wish they could fly like a bird. But which kind?

“Don’t wish to be an eagle or hawk if you’re planning on going fast,” says Chase Mendenhall, the William and Ingrid Rea Assistant Curator of Bird Conservation. “Because they’re basically the station wagons of the sky.”

If you think about it, there are many different styles of flight. And Nature’s Amazing Machines shows us how each style is achieved physically and what a certain species might gain from evolving in that direction.

Birds with long, narrow wings (top) use them to ride gradients of moving air over flat water and save energy for long-distance flights, while those with shorter, sharp wings can beat them rapidly to obtain fast flight speeds.

Large birds of prey and vultures have enormous, broad wings that allow them to fly slowly by relying on rising warm air to take them high into the sky. This also allows them to cover vast territories while expending minimal energy. On the other end of the spectrum, a duck’s short, sharp wings beat rapidly to obtain fast flight speeds. In fact, duck wings are shaped rather like those of a falcon, which sometimes eats ducks, says Mendenhall. And then you have birds somewhere in between, like the blue jay, which has short, stubby wings that allow it to fly relatively slowly while maneuvering through the forest.

Best of all, Nature’s Amazing Machines takes the hypothetical and makes it experiential by allowing visitors to sit in a spinning chair and propel themselves with fans that mimic bird wings. A short, wide fan gets you moving quickly but requires constant wingbeats to keep the chair moving—quack quack! Likewise, the long, narrow fan requires more work to get started, but once you’re airborne, so to speak, you can keep spinning with minimal effort.

All of this is mirrored in our own flying machines, by the way.

Don’t wish to be an eagle or hawk if you’re planning on going fast. Because they’re basically the station wagons of the sky – Chase Mendenhall, the William and Ingrid Rea Assistant Curator of Bird Conservation

“The same way you can look at an airplane and guess what that airplane is good at, you can look at a bird’s wings and guess at what it’s good at,” says Mendenhall.

The Wright brothers observed birds before they ever left the ground, of course. And much of that research focused on how the curved shape of a bird’s upper wing creates lift. Today, we call these structures airfoils, and they’re used in everything from airliners and propellers to turbine blades.

It’s Not A Competition

While it’s clear humans owe a great deal to nature’s technological inspirations, the exhibit also reveals some interesting tensions.

“I think there’s a tendency to kind of think of these machines as superior to animals,” says Mendenhall.

And while human scientists have certainly come a long way in advancing fields such as robotics—the exhibit features MABEL, the world’s fastest two-legged robot—we still have a long way to go before we catch up with the natural world, says Mendenhall.

For instance, we still don’t really understand how photosynthesis works, he asserts, and that’s a process mastered by plants and even some animals, including the giant clam, which can feast on sunlight thanks to a partnership with algae.

The largemouth bass gulps down huge fish with its gaping jaws. Thanks to its linkages, it can open its mouth the height of its entire body.

“These are things that could solve major problems in the world if we figure them out,” says Mendenhall. “So, our machines are kind of stumbling way behind nature.”

Or consider the sling-jaw wrasse. These coral-reef fish attack shrimp by extending their jaws two-thirds the length of their own heads, kind of like the movie monsters seen in the Alien franchise. Using some of the same bones and ligaments, but in a different arrangement, the largemouth bass opens its mouth as wide as it is tall, which allows it to gulp down prey in an instant.

“You know, a fish eating its food might not seem that interesting,” says Seago, “but there are dozens and dozens of people out there who have spent their entire PhDs on all the different feeding mechanisms they use.”

Rather than seeing the mysteries underlying these mechanisms as a shortcoming of human progress, these exhibits are meant to inspire. From the stretchy throat of a pelican to the fluid-driven limbs of a spider, there’s wonder everywhere.

As Mendenhall notes, “It kind of gives you an idea of how, in a way, these everyday animals have superpowers.”

Nature’s Amazing Machines was developed by the Field Museum, Chicago, in partnership with the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, with generous support provided by the Searle Funds at the Chicago Community Trust and ITW Foundation. Major support for CMNH’s presentation of Nature’s Amazing Machines is provided by PPG and PPG Foundation. The exhibition is sponsored by Cook Myosite, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, Dollar Bank, and PA Virtual Charter School.