Facing a global outbreak of the disabling disease yaws in the 1950s, the United Nations Children’s Fund and World Health Organization launched a campaign to bring penicillin to 46 countries.

Early into that 12-year campaign, James Swauger and Don Dragoo, two archaeologists with Carnegie Museum of Natural History, created a panel display about the efforts to defeat yaws. But they were more concerned with a different problem—racism. Their panel sought to dispel the myth that some “races” were more susceptible to disease than others.

“Children are the same everywhere,” the text read. Pictures of those children framed a globe, with arrows pointing to the regions where they lived. It spoke to the biological unity of human beings.

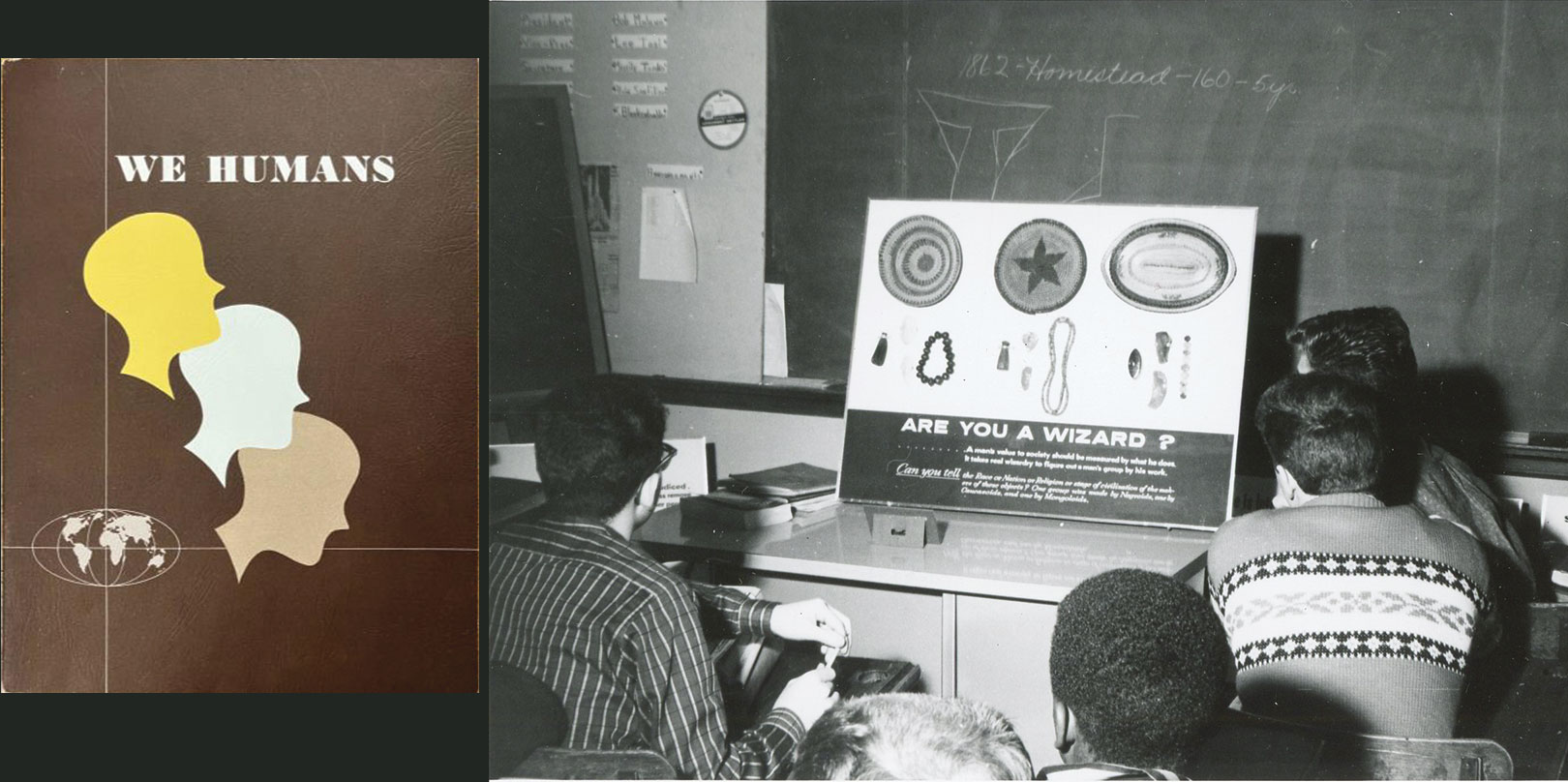

In 1955, the panel became part of a groundbreaking exhibition about race, We Humans. Its collaborators—the United Steelworkers (USW), Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the city of Pittsburgh, and Pittsburgh Public Schools—believed that individuals had the power to conquer racism.

“It’s really valuable to see that in 1955, the highest people in power in Pittsburgh were making anti-racism a priority,” says Deirdre Smith, curator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, who worked with University of Pittsburgh senior Lindsey Kenny to curate the exhibition, We Humans at 70: Educating Pittsburgh on Race in the 1950s. The exhibition is on view at the University of Pittsburgh’s Hyland Gallery at Hillman Library through July 2026.

“In many ways, we face unique challenges, but these aren’t necessarily new challenges,” adds Ron Idoko, associate director of the Center on Race and Social Problems at the University of Pittsburgh. “We learn from our history.”

We Humans grew out of the USW’s Civil Rights Committee joining the nationwide reckoning over the Holocaust and the dangers of claiming racial purity and superiority. It was the early years of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education ended “separate but equal” school systems. The following year, 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi.

Swauger and Dragoo curated the original exhibition, filling four cases and eight panels with objects from the museum’s anthropology collection alongside graphic and written materials. They interpreted the contents through the theory at that time that only scientists were qualified to determine someone’s race. (We now know there is no genetic basis to racial categorization.)

“Scientists are obligated to make certain that facts on inter-group relationships are understood by everyone,” then-Director of the Museum of Natural History M. Graham Netting told The Pittsburgh Press. “In this project, we are doing our part to help alleviate tensions and do away with prejudices.”

“It’s really valuable to see that in 1955, the highest people in power in Pittsburgh were making anti-racism a priority.”

Deirdre Smith, curator, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

The displays emphasized human universality as well as the contributions of each “race.” One case of woven and beaded artifacts from around the world was presented without identifying labels, telling viewers that only a wizard would be able to discern their origin or determine which was superior. “If you needed one of these baskets or one of these mats, would it really matter who made it?”

One image featured a besuited white man at a diner counter. “If you insist on being prejudiced,” it asked, “why not have the waitress remove the breakfast items other peoples developed?” To do so would leave the man without oatmeal, potatoes, wheat toast, sugar, and coffee.

We Humans received mostly positive attention, Smith says. The editorial board at the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph praised the project: “You can help fight this ‘social cancer’ by making up your mind that you are NOT naturally better than others.” A letter to the editor, however, called the project “propaganda” and said that embracing it would invite a communist takeover.

Then, as now, progress was muddled. Each partner behind We Humans simultaneously acted in contradiction to the exhibition’s purpose. The USW’s Civil Rights Committee ran without Black leadership. Mayor David L. Lawrence oversaw the demolition of the Lower Hill District in 1955, disproportionately affecting the Black community in ways still evident today. The Museum of Natural History’s collection contained stolen human remains. (The museum is currently repatriating those remains.) In 1956, the first portable version of We Humans went to Schenley High School, whose student population was nearly 46 percent Black but had only four Black teachers.

Portable versions later went beyond Pittsburgh to institutions like the San Francisco Public Library. A version also remained on display in the Museum of Natural History until at least 1969.

This look back at the original exhibition underscores how much has changed in 70 years, and how much hasn’t.

“Our understanding of what racism is has vastly changed,” says Gina Winstead, vice president of culture and community at Carnegie Museums. “Previously, racism was seen as an individual choice. Now we have a better understanding that if a group of people made the choice to be racist, then they implemented racist systems, laws, and policies.”

However, she adds, those systems still exist even though there’s increasing awareness.

In revisiting the intents and flaws of We Humans, Smith asks, “How can it help you act differently in the present? What will people in the future say about the anti-racist work of today?”

Winstead adds, “If they could come up with something that worked for them to have constructive conversations about race in 1955, we absolutely can in 2025.”