About 52 million years ago, alligators slid through the swamps of the High Arctic. These were not wayward reptiles. The saurians thrived in a warm, lush environment at 75 degrees north latitude. What remains of the habitat is preserved in the rocks of Canada’s remote Ellesmere Island—a lost world uncovered by fossil hound Mary Dawson.

From feature films to magazine spreads, there’s a stereotyped image of who a paleontologist is. That person is often a scruffy-looking man in a broad-brimmed hat who scours remote deserts in a race to find unknown dinosaurs. Mary Dawson, who passed away at age 89 in late 2020, was the polar opposite of this image. Soft-spoken, tenacious, equally brilliant and generous, Dawson was an Arctic pioneer who helped transform the field of paleontology inside and out. She did so, her colleagues recall, by being herself and keeping her eye on what she wanted to accomplish, blazing a trail for others in the process.

Mary Dawson studying a Prolagus skeleton early in her career at the museum, ca.1966.

A Michigan native, Dawson started her formal studies at Michigan State University, where she set her sights on veterinary medicine. But over time her attention was drawn further into the past, to the mammals that populated the planet over the past 66 million years. In 1958, Dawson completed her doctorate at the University of Kansas, where she conducted groundbreaking research on fossil rabbits and hares of North America. These mammals, along with ancient rodents, would become Dawson’s core research subjects, although those studies were only part of an extraordinary legacy that includes game-changing fossil discoveries, a Fulbright scholarship, the prestigious Arnold Guyot Prize from the National Geographic Society, and a slew of researchers she mentored who still carry out fieldwork around the world.

Arctic Pioneer

Carnegie Museum of Natural History and a sheep farm north of Pittsburgh would become Dawson’s home bases for a remarkable 57 years, and her demanding schedule as a research associate in the 1960s wasn’t that different from her schedule as a curator emerita. From the start, Dawson bridged the past and present in many ways.

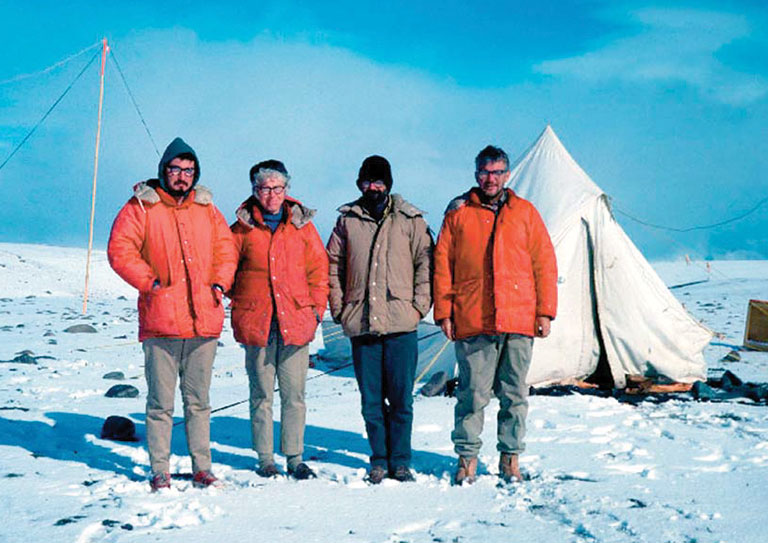

Mary Dawson (second from left) with Robert “Mac” West, J. Howard Hutchison, and Malcolm McKenna in 1976 at Strathcona Fiord. It was the year they found the “gold” for which they had been searching since 1973—jaws and teeth of Eocene mammals. Photo courtesy of Mac West.

(Left to right)Hans de Bruijn,Mary Dawson, and Robert (Mac) West board a twin otter at Resolute Bay, Cornwallis Island en route to Ellesmere Island (1979). Photo courtesy of Leo Hickey.

“I still work in the north and have challenges at times. I’ll often ask myself what Mary would do. Mary broke the mold. She is an Arctic pioneer. She is the Arctic pioneer of paleontology.”

– Jaelyn Eberle, University of Colorado Boulder paleontologist

The Eocene alligators of Ellesmere were one of her earliest and most influential successes. During the 1970s, when she began working with Milwaukee Public Museum paleontologist Robert “Mac” West, the idea that continents moved and dramatic fluctuations to Earth’s climate had occurred over vast stretches of time were still new theories. With that in mind, Dawson set about searching for Arctic fossils that might help elucidate how animals moved around the world as Earth’s continental plates shifted through time.

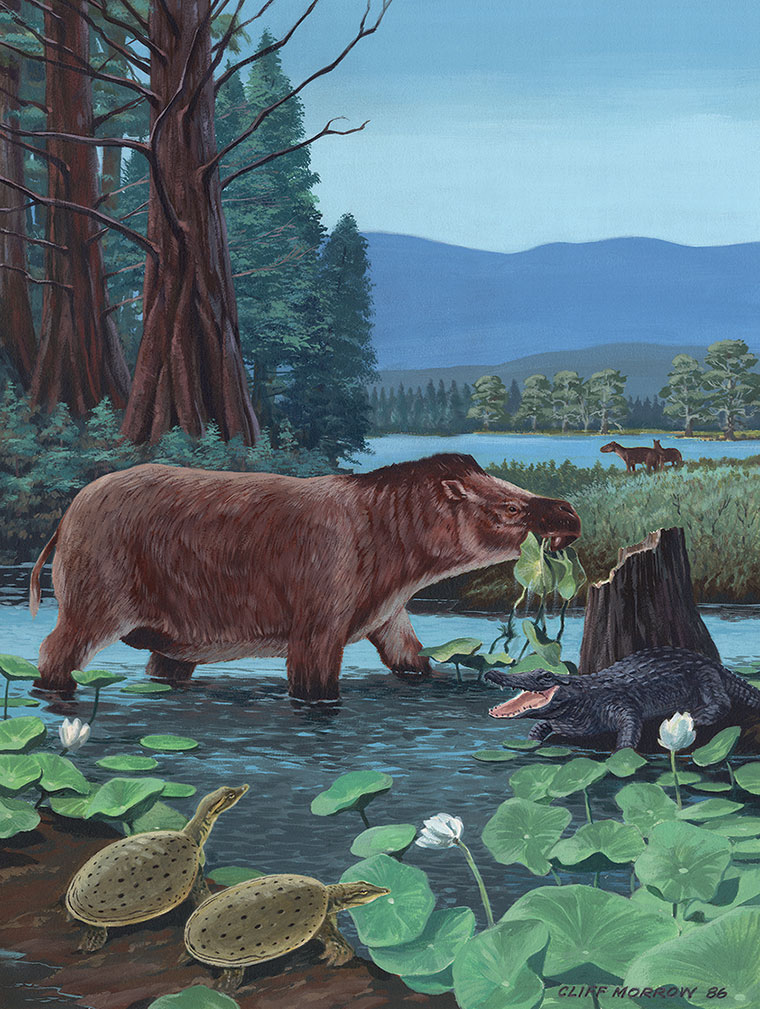

Early Eocene fauna of Ellesmere Island, including a Coryphodon (center) and Arctic alligator, based upon discoveries by Mary Dawson and collaborators. The 1986 painting is by Cliff Morrow, former head of exhibits at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

When Dawson and West published their early finds in 1976, colleagues were shocked. Among the landmark discoveries from those early explorations were the first fossil mammals ever found in the Arctic, including a hippo-like creature called Coryphodon. These finds were not only firsts for the region, they also established that there was once a connection between ancient North America and Europe. More than that, the 52-million-year-old rocks of Ellesmere Island contained the remains of a much warmer environment, a fact that piqued the curiosity of other researchers. Experts on prehistoric climates, fossil pollen, ancient plants, and more started thinking about the Arctic as a keystone to understanding how dramatically Earth has changed.

Matriarch of Vertebrate Paleontology

Dawson ventured to the top of the world again and again—11 times in total—to look for more fossils while creating a landmark paleontology program at Carnegie Museum, overseeing the fourth largest vertebrate fossil collection in North America. She became, as her successor Matt Lamanna puts it, “the matriarch” of the museum’s most famous section. Not bad for a scientist who, when promoted from research assistant to assistant curator in just a year’s time, was told that no woman would ever head the department—a title she would later hold for 30 years.

In July 2007, Mary Dawson (right), Natalia Rybczynski (left) of the Canadian Museum of Nature, and then-student Liz Ross found a small carnivorous mammal known as Puijila (pictured below) in 23-million-year-old lake deposits on Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic. Photo: Martin Lipman

Given Dawson’s research interests, the museum’s paleontology section has a strong focus on fossil mammals. Dawson trained and carried out studies with experts such as paleoprimatologist Chris Beard, now at the University of Kansas, and early mammal expert Zhe-Xi Luo of the University of Chicago, who chose to work at the museum partially based on Dawson’s reputation. Luo considers Dawson “the North Star” of his generation of vertebrate paleontologists.

Given that Carnegie Museum of Natural History is famous for its essential collection of Jurassic dinosaurs, Dawson had a sense of humor about which fossils drew the crowds and which drove the museum’s research program.

“Mary and I would tease one another relentlessly,” says Lamanna, the museum’s head paleontologist and dinosaur researcher whose official title is the Mary R. Dawson Associate Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology. “A lot of the barbs she threw my way had to do with how dinosaurs were so lame and uninteresting compared to mammals,” Lamanna says with a laugh. But Dawson was clearly only half serious. Recalling an episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood when Dawson gave Fred Rogers a tour of the old Dinosaur Hall, Lamanna recalls, “She did at least as good a job telling him about our dinos as I could.”

Mary Dawson with Fred Rogers in 1980.

Dawson’s knowledge and spirit shone through all facets of her work. And she always made time for curious students and early career scientists. “Mary was the type of person who, if you expressed an interest in something related to vertebrate paleontology, she would go out of her way to help you get started,” says Amy Henrici, the section’s longtime collections manager. In fact, that’s exactly how Henrici became one of Dawson’s graduate advisees.

Mary Dawson and collaborators on Devon Island in 2007.

University of Colorado Boulder paleontologist Jaelyn Eberle was also influenced by Dawson. The two worked together in the Arctic during the 2001 and 2002 field seasons, when Dawson was in her early 70s. “Mary’s a quiet person in the field, but when she says something, you listen,” Eberle recalls. Watching Dawson work, she says, is what eventually helped inspire her to run her own expeditions.

Her Own Breed

Dawson’s other true love was Bernese mountain dogs, and she earned distinction as a nationally recognized judge of the breed.

Her two areas of expertise sometimes came as a surprise to her colleagues as well as to the people who knew her first from the dog world. “I worked at the Canadian Museum of Nature for two years,” Eberle recalls, “and one day I talked to this person who owned a Bernese mountain dog. I had been planning on seeing Mary soon, and mentioned her name.” The new acquaintance was shocked. “You know Mary Dawson?” they asked, incredulous. Henrici, too, had a similar encounter with a star-struck Bernese mountain dog owner in Kansas, as Dawson was as much of a big name in the dog show world as in paleontology.

Mary Dawson and Alice Guilday with Mary’s prized Bernese mountain dogs.

In 2002, Dawson became the first American woman to garner the Romer-Simpson Medal from the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology for her work in the Arctic and her research on rodents and rabbits. That same year, at age 71, she retired from full-time work but kept uncovering new fossil secrets whether in her museum office or in some distant locale.

In 2005, a group of researchers named a new rodent species that had turned up in a meat market in Laos. Dawson immediately recognized that this was no ordinary animal. “I remember Mary telling me how as soon as she read the scientific description, she noticed remarkable similarities between this beastie and the fossil rodents of the family Diatomyidae,” Lamanna says, meaning that the new species belonged to a fossil lineage that was thought to have gone extinct 11 million years ago. Dawson published the alternative interpretation the following year, and her insight into the rodent’s true identity, Lamanna says, is a testament to “how creative, perceptive, and even bold a scientist she was.”

Dawson was involved in an equally impressive find the next year. She was doing Arctic fieldwork in the Haughton impact crater when the field crew’s ATV ran out of gas. While several members of the team started the long walk back to camp, Dawson and then-student Elizabeth Ross poked around the stranded vehicle. The unassuming patch of ground was brimming with bones, eventually announced as the nearly complete skeleton of a new mammal named Puijila—a transitional fossil that fits between seals and their terrestrial ancestors.

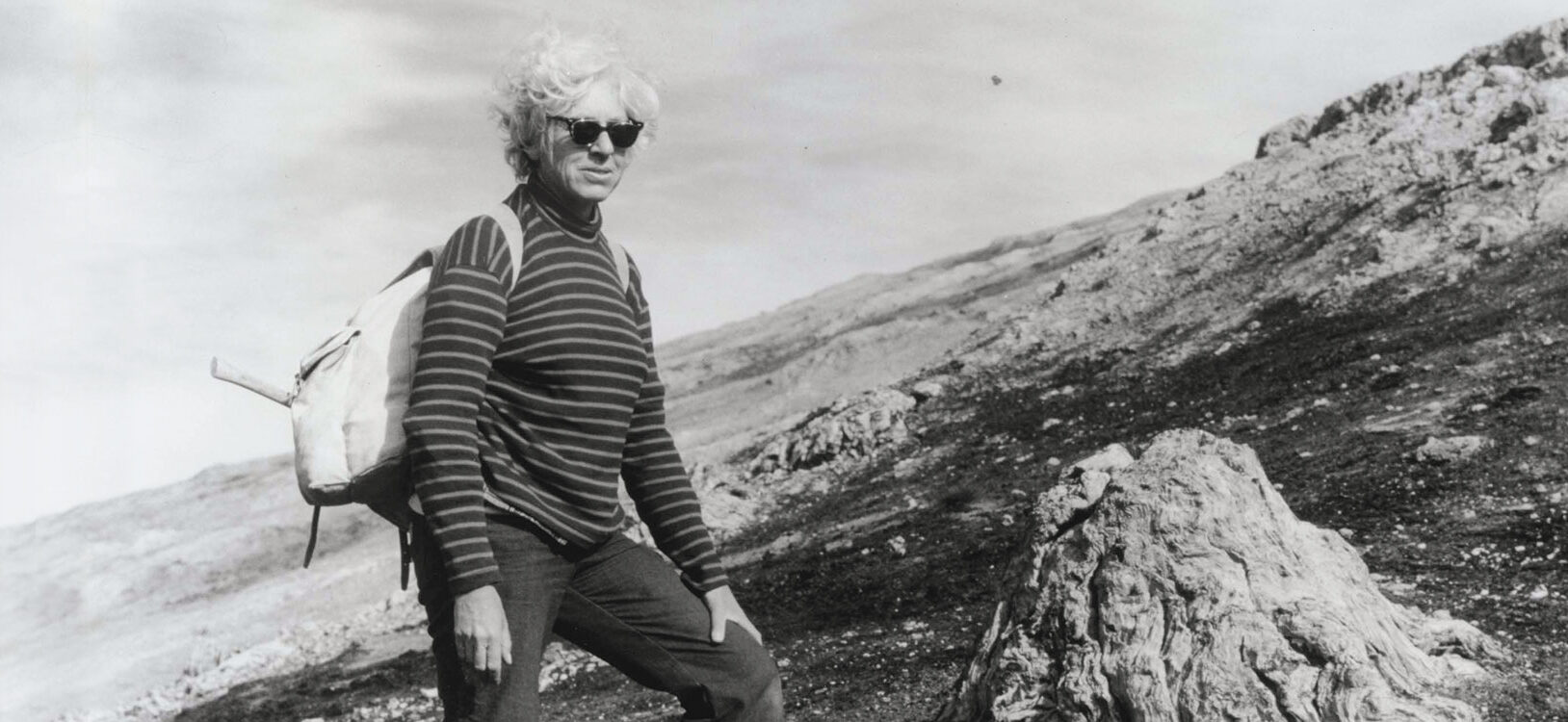

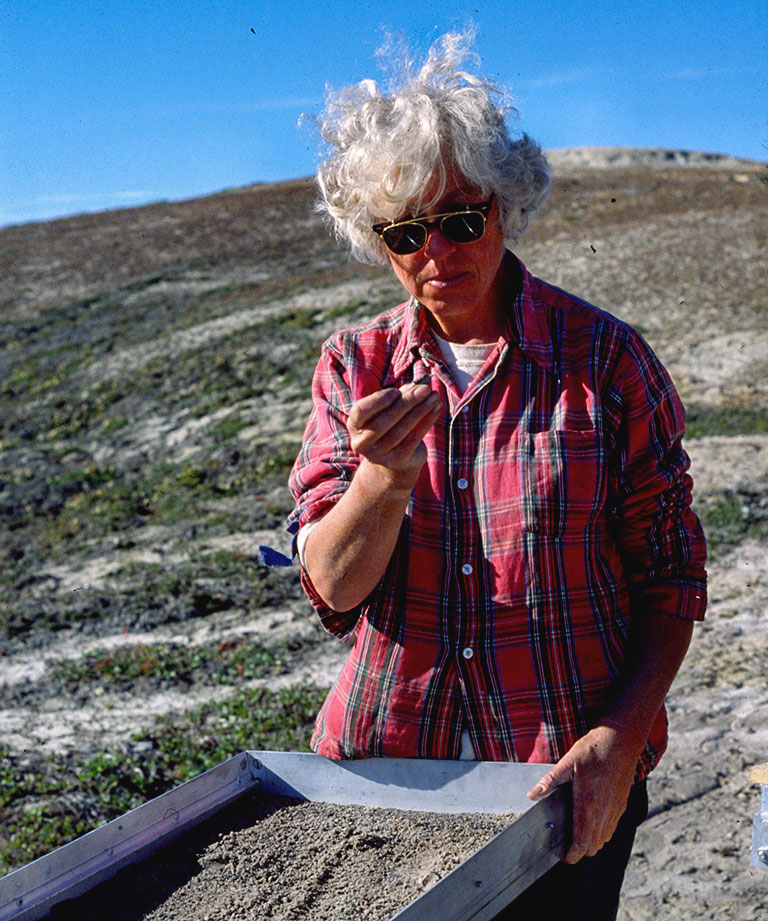

Checking screens on Ellesmere Island, 1970s. Photo: Mac West

Camp time in the Canadian Arctic, 1987. Photo: Malcolm McKenna

Through it all, Mary kept her trademark sense of wonder. “One day in Haughton crater,” recalls Canadian Museum of Nature paleontologist Natalia Rybczynski, “we became very concerned when a polar bear showed up and approached camp.” The crew worried as the bear started coming faster, but most everyone breathed a sigh of relief when it disappeared behind a hill. Except Mary. “Mary was upset, too, but only because she did not get to see the bear!” Rybczynski laughs.

“I still work in the north and have challenges at times,” Eberle says. When they present themselves, “I’ll often ask myself what Mary would do. Mary broke the mold. She is an Arctic pioneer. She is the Arctic pioneer of paleontology.”

Mary Dawson in 2007 in Haughton impact crater, where she and collaborators found Puijila. Photo Martin Lipman