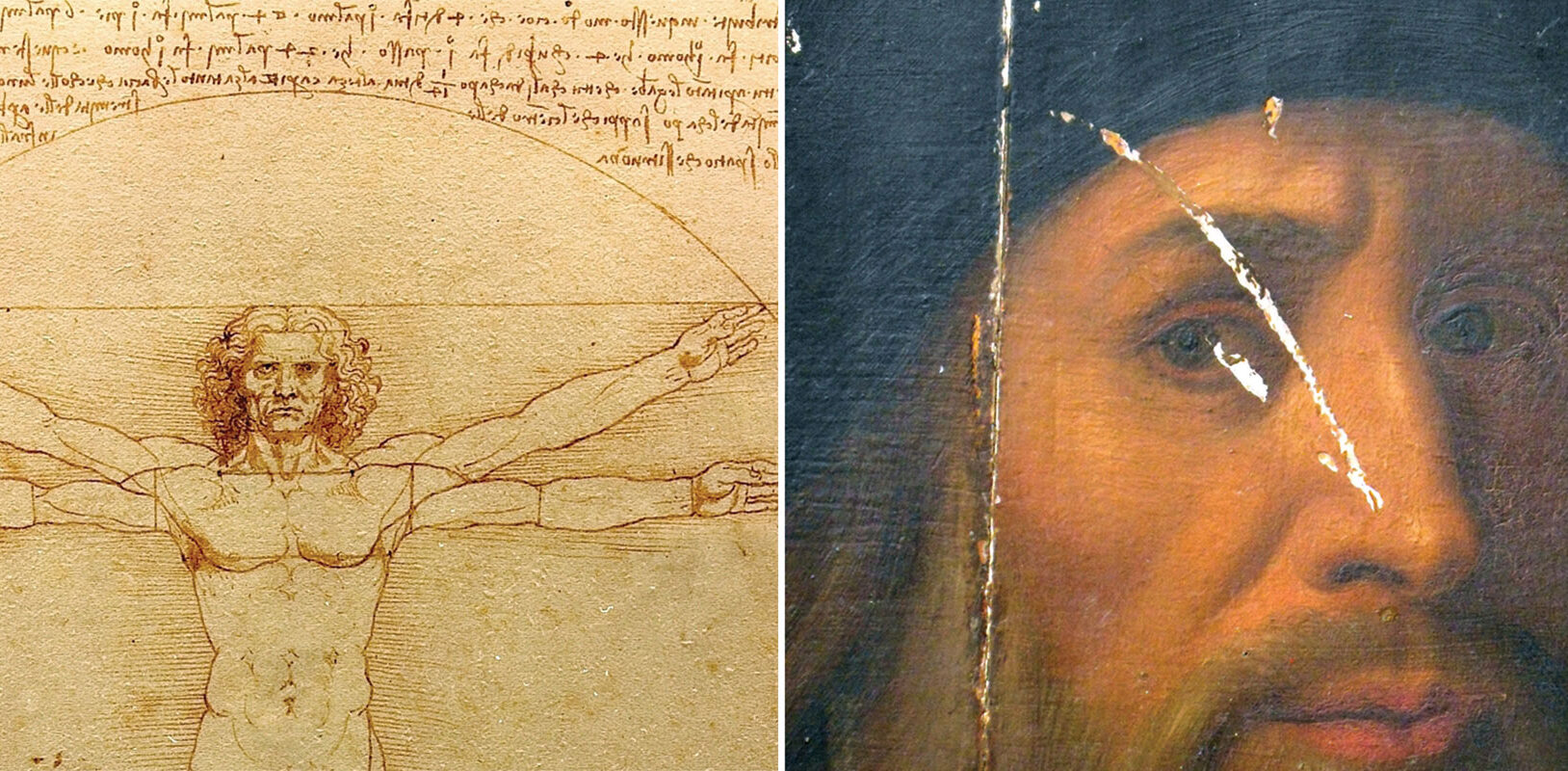

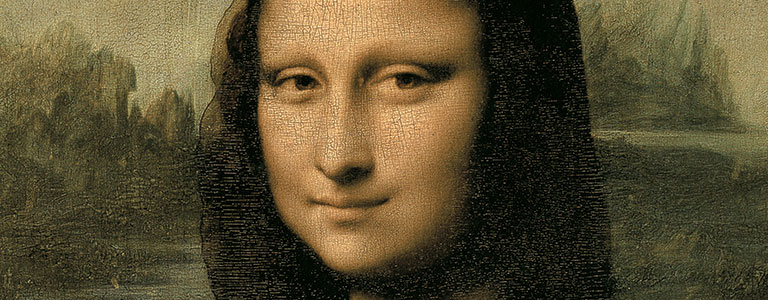

A detail of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

With an enigmatic smile, she looks out from the wall of the Louvre. Art collectors and schoolchildren alike know her famous face from art history books, advertising campaigns, and pop culture parodies. She’s the Mona Lisa—the masterpiece of the original Renaissance man, Leonardo da Vinci.

Unquestionably one of history’s greatest artists, Leonardo (da Vinci is not a surname, rather a reference to his hometown) is less well known but perhaps equally accomplished as a scientist. His insatiable curiosity propelled him to query the world around him—from anatomy to architecture, water flow to weapons, the curvature of the human spine to the tongue of a woodpecker.

Upon the 500th anniversary of his death, Da Vinci The Exhibition, on view at Carnegie Science Center’s PPG Science Pavilion™ through September 2, takes visitors back in time to discover one of history’s most forward-thinking figures. Featuring more than 60 life-size reproductions of Leonardo’s inventions, more than 20 fine-art replicas, and an activity zone inspired by the genius himself, Da Vinci The Exhibition explores his wonderous creative process.

The depth of Leonardo’s forays into so many unique disciplines is partly responsible for the relative scarcity of his authenticated paintings—just 19, and some of them are unfinished. To Leonardo, art and science were intertwined in his quest for the truth.

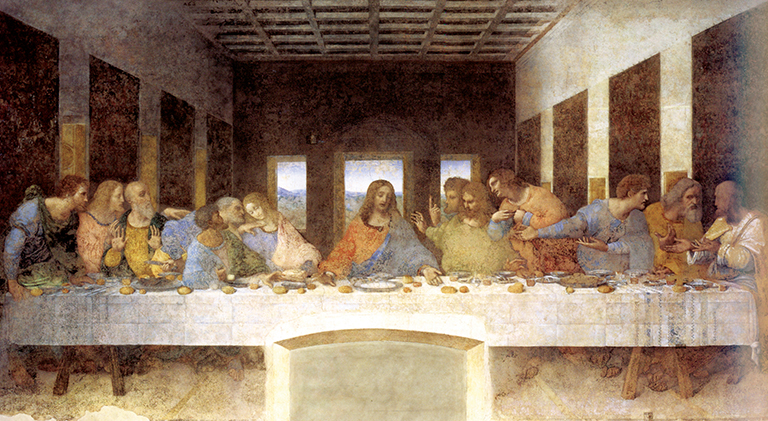

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, c. 1498

“It was all part of one big investigation,” says Martin Clayton, a leading Leonardo scholar and head of prints and drawings for Royal Collection Trust in London. “He regarded art as having a scientific basis. He regarded science as having an artistic basis. He saw the forces of nature as being so elegant and believed there was something beautiful and artistic about the way the universe arranged itself.”

That attitude was nurtured in 15th-century Florence, the cradle of the Italian Renaissance, when economic prosperity led to great strides in the arts and sciences. Born out of wedlock on April 15, 1452, illegitimacy prevented Leonardo from going to university. He apprenticed in the studio of Florentine painter Andrea del Verrocchio.

Leonardo would become a striking figure in his fur-lined cloaks and pink silk stockings. A great conversationalist, he was popular with both his intellectual friends and royalty. He was also a bit of a rebel—“gay, vegetarian, left-handed, easily distracted, and at times, heretical,” Walter Isaacson wrote in his 2017 biography, Leonardo da Vinci.

Pioneering anatomist

That rebel persona allowed Leonardo to look at things in new ways—especially the human body. Intent on instilling his human figures with a lifelike quality, he performed dissections on cadavers resulting in anatomical drawings that were astoundingly detailed and accurate for the time. As he gained mastery of the human form, he sometimes returned to earlier works.

He was able to correct his original drawing and get the neck muscles right in Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, Clayton noted. In his obsessive painting and repainting of the Mona Lisa, his focus on her eyes and facial muscles helped “create a smile that seemed to flicker on and off,” Isaacson wrote.

Leonardo used observations and sketches of real people to create the emotions of his subjects, says Clayton. But what began as an artistic exercise quickly pulled him in another direction—a 15th-century exploration of the way the brain communicates with the facial muscles to express emotions.

“Right from the start, he was going much deeper than most artists would go,” says Clayton, author of Leonardo da Vinci: A Curious Vision, among other books. “He wanted to find the neurological basis of emotion, expression, and pose, and surprisingly he found it impossible to make more than the most superficial observations.”

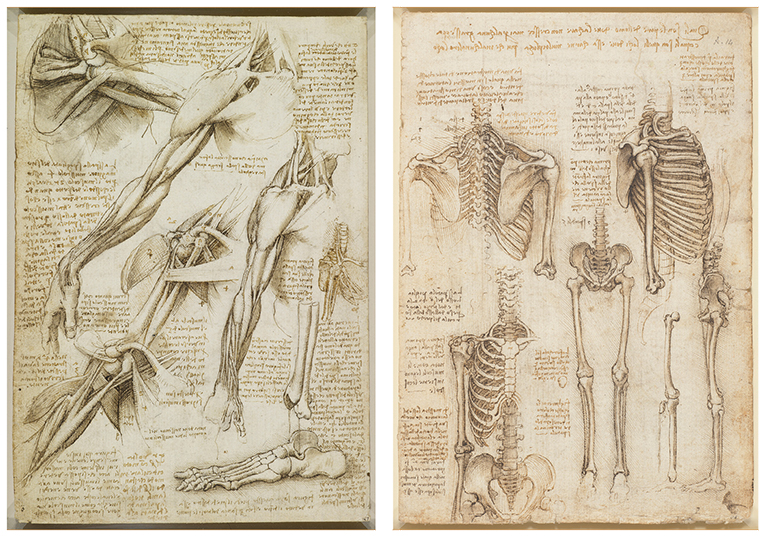

Leonardo’s intricate knowledge of the human body is demonstrated in a collection of notebooks, dated between 1492 and 1519, which he filled with detailed studies of organs, bones, vessels, and muscles using new illustrative techniques. He began the research to ensure his artworks were as accurate as possible. Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

Leonardo’s efforts to understand the human figure as an artist also made him a pioneering anatomist. “He was the first one to draw the vertebral column with the correct number of vertebrae,” says Ron Philo, co-author with Clayton of the books Leonardo da Vinci: The Mechanics of Man and Leonardo da Vinci: The Anatomy of Man.

“He put the curvature of the spine in before everyone else. He understood that the center of gravity was in the sacral area,” says Philo, adjunct associate professor of cell systems and anatomy for Long School of Medicine at UT Health San Antonio.

Having only seen the anatomical drawings in books, Philo was astounded when he saw in person Leonardo’s exquisitely detailed drawings at the Royal Collection Trust in Windsor. “You wouldn’t believe that someone had done this by hand. He had a very fine hand and extremely good instruments. I have used his drawings to teach modern-day anatomy.”

“He regarded art as having a scientific basis. He regarded science as having an artistic basis. He saw the forces of nature as being so elegant and believed there was something beautiful and artistic about the way the universe arranged itself.”

– Martin Clayton, Leonardo scholar

Leonardo also made a study of the heart, and his conclusions put him centuries ahead of his contemporaries. To visualize the organ’s functions, he made a wax cast of the cavities in an ox heart and used it as the mold for a glass model. By pumping water through the glass, he discovered that the aortic valves are not closed by muscle but by the backflow of blood.

That was in 1512. It wasn’t until the 1980s that science fully understood the mechanisms of the valves. “It was an extraordinary investigation of the functions of the heart,” says Clayton.

A scientist who paints

Leonardo wanted to publish his scientific studies, but as a perfectionist he was never satisfied that he knew enough to conclude his research. Very few of his contemporaries even knew the renowned artist was also a scientific genius. “Leonardo’s reputation was and to some degree still is, that of a painter who made crazy inventions,” Clayton explains.

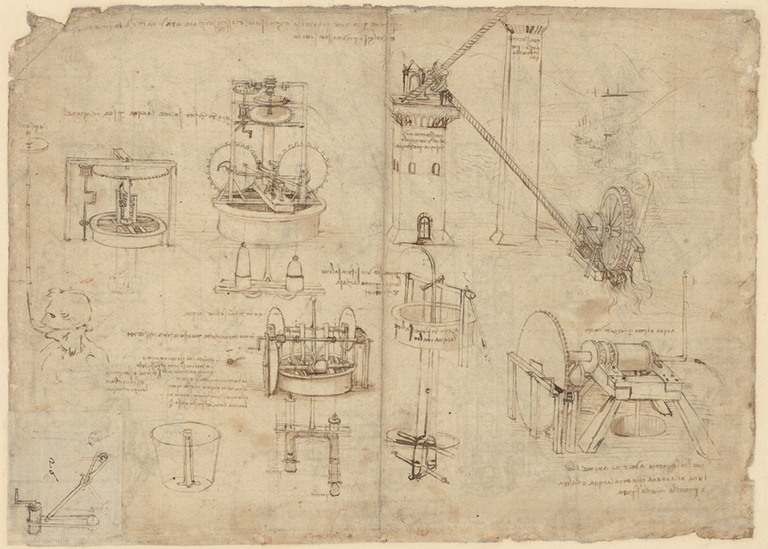

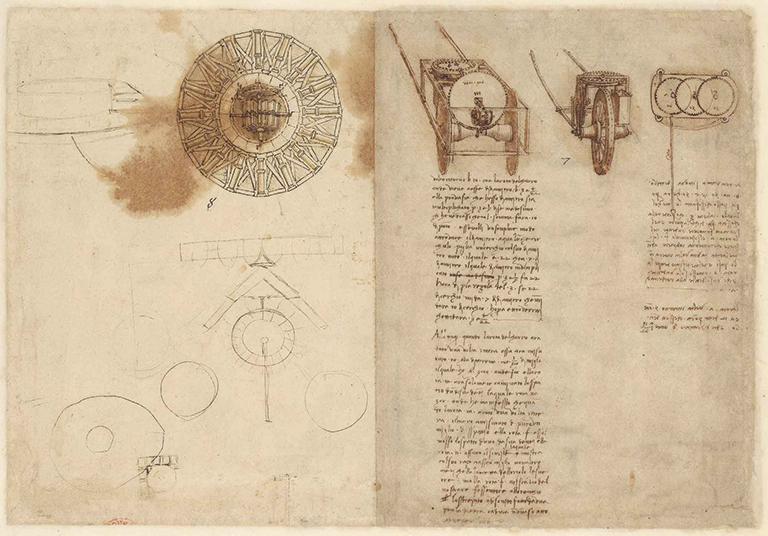

His work may have been lost to history had Leonardo not kept scrupulous notes—thousands of pages of sketches, diagrams, and musings for his personal use, written in a backwards “mirror style” by the lefty. Fortunately, he used good-quality paper that has preserved his handwriting over five centuries.

He left his notebooks to an apprentice, and after changing hands three times they were published in the late 19th century. Only then did the public grasp the scope of his achievements. The notebooks are now under the care of various museums. In 1994, Microsoft founder Bill Gates bought a Leonardo notebook for more than $30 million, which he has loaned out for exhibitions.

The notebooks offer a tour inside a mind that never stopped making the kinds of connections that others had yet to imagine.

In his notebooks, Leonardo described and sketched ideas for many inventions hundreds of years ahead of their time. He wrote his notes backwards, starting from the right side of the page and moving to the left. Theories abound about why he did this, including the simple explanation that he was left-handed and writing in this way didn’t smudge.

Each invention featured within Da Vinci The Exhibition was handcrafted using a modern translation of Leonardo’s unique mirrored writing style. Trained artisans used these translations to construct full-scale models and bring the two-dimensional plans to life.

He jotted down “math calculations, sketches of his devilish young boyfriend, birds, flying machines, theater props, eddies of water, blood valves, grotesque heads, angels, siphons, plant stems, sawed-apart skulls, tips for painters, notes on the eye and optics, weapons of war, fables, riddles, and studies for paintings,” Isaacson wrote. “The cross-disciplinary brilliance whirls across every page, providing a delightful display of a mind dancing with nature.”

Paper was expensive then, so Leonardo crammed a lot of information onto the pages of his notebooks, finding connections between various disciplines. For example, he might sketch a dome on a chapel and then study the structure of the skull as the perfect dome-like structure because it protects the brain. By studying the skull, he gleaned information on how to build a dome.

Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci, c. 1476

His studies of light were also ahead of his time, as reflected in the subtle glazes he applied to Mona Lisa’s smile. “He was also aware of peripheral vision and that things look different as the eye moves around. Something seems to be shifting on the smile as the eye passes over it,” Clayton says.

Like the Impressionists of the 19th century, Leonardo played with color and light. “He knew that colors took on the blush of the objects nearby,” Clayton says, as Claude Monet did centuries later.

A self-styled architect and engineer, Leonardo also made detailed drafts of three-dimensional buildings. While many completed architectural plans appear in his notebooks, Clayton notes that it’s not known whether any of them were built. The notebooks also show that Leonardo had a fascination with weapons. “He had an almost childlike love of inventing guns and cannon,” Clayton says.

As his life progressed, Leonardo’s focus shifted toward his scientific endeavors. “For the first part of his career, he was a painter who was a little bit interested in science,” adds Clayton. “In the latter part of his life, he was a scientist who was interested in art.”

Even now, there are those who believe the world was robbed of art by Leonardo’s obsessive pursuit of science and his inability to finish what he started.

“Maybe he did take things too far, but it comes with the territory,” Clayton says. “You can’t criticize someone for perfectionism on one hand, then marvel at how insightful their investigations were on the other hand.”

For Isaacson, who has authored the biographies of other visionaries such as Steve Jobs, Ben Franklin, and Albert Einstein, Leonardo stood out among the great men of history for his freewheeling and childlike curiosity.

As he put it, “He was the one person who most wanted to know everything that could be known about everything in creation, including how we humans fit into it.”

Da Vinci The Exhibition is a hands-on examination of the Renaissance master’s life, research, and art, with more than 60 fully built, life-size inventions and more than 20 fine-art studies to explore. It’s on view at Carnegie Science Center through September 2.

Da Vinci The Exhibition is developed by Aurea Exhibitions and produced by Imagine Exhibitions, Inc. At Carnegie Science Center it is generously supported by EQT Foundation and sponsored by Agora Cyber Charter School, Citizens Bank, and Renewal by Andersen.