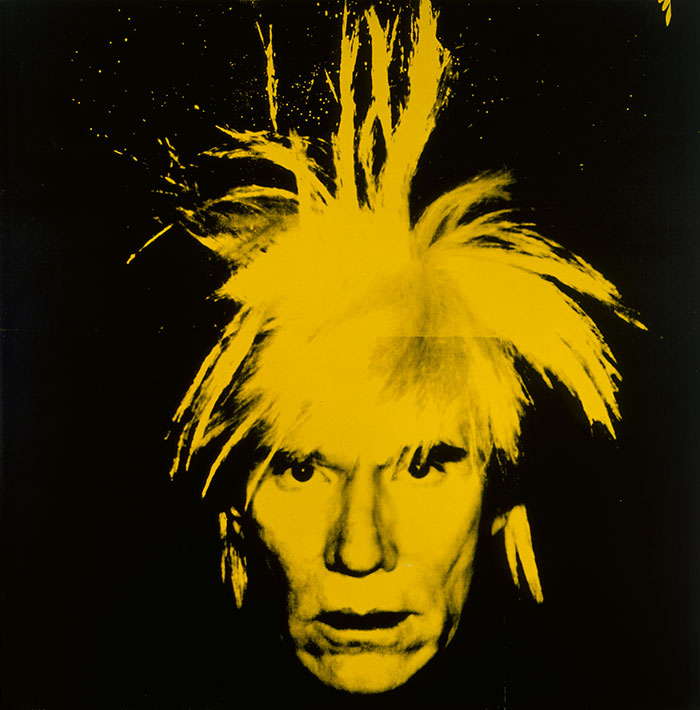

Leaving the house was no small feat for Andy Warhol. Before stepping out into the nightlife, he first had to “glue myself together,” as he often said. His biographer Wayne Koestenbaum described a “process of self-repair” that Warhol used to overcome his insecurities—dyed eyebrows, makeup, and the wigs that he used to conceal his premature balding.

Warhol’s routine featured an array of lotions and potions—health, beauty, and anti-aging products meant to keep him looking and feeling as young and vibrant as the stars in his orbit. An advertisement for one piece of his expansive collection, a night treatment cream made by Giorgio Beverly Hills, laid bare the message underlying all of this labor: “Introducing the extraordinary new way to buy time.”

Once part of Warhol’s medicine cabinet, the cream is now a revealing element in Time Capsule-20, a collection of items featured in Andy Warhol: Vanitas, an exhibition that explores the artist’s contemplation of mortality, vanity, and the fleeting nature of beauty and life itself. The exhibition runs through March 9, 2026, at The Andy Warhol Museum.

Vanitas shines a light on Warhol’s fascination with the temporality of life, says Patrick Moore, the museum’s former director, who curated the exhibition in collaboration with the Netherlands’ SCHUNCK Museum.

“Whether it’s the flowers in the flower paintings or the celebrities in the great celebrity portraits,” Moore says, “Warhol always looked at them as tragic in some sense, in that their beauty and their fragility was a reminder of how short life is.”

A Centuries-Old Tradition

Those themes are central to Vanitas (Latin for vanity), a genre of still-life painting that emerged in the Netherlands in the 17th century, with an emphasis on symbols of the futility of earthly endeavors in the face of mortality. The paintings are littered with memento mori, or reminders of the inevitability of death: extinguished candles, wilting flowers, hourglasses, and skulls. Although it’s unknown exactly which Vanitas pieces may have inspired Warhol, he was a student of art history who visited the Netherlands and its Rijksmuseum—home to masterpieces in the Vanitas tradition, including some featured in the exhibition—and he pondered many of the same ideas in his own work, says Amber Morgan, The Warhol’s director of collections and exhibitions.

“Whether it’s the flowers in the flower paintings or the celebrities in the great celebrity portraits, Warhol always looked at them as tragic in some sense, in that their beauty and their fragility was a reminder of how short life is.”

Patrick Moore, former director of The Andy Warhol Museum

When SCHUNCK and The Warhol sought to collaborate, it felt natural to explore the themes of the Vanitas genre, according to Fabian de Kloe, SCHUNCK’s artistic director. De Kloe and his colleagues admired Revelation, a 2019 exhibition at The Warhol that focused on Warhol’s Catholic upbringing and its influence on his art. Drawing out the connections between Warhol’s work and the Vanitas tradition offered the opportunity to delve deeper into some of the ideas raised in Revelation, de Kloe says. Vanitas was first shown at SCHUNCK beginning in September 2024 and serves “almost like a second chapter” to Revelation, Morgan says.

“It’s not really about religion,” she continues. “It’s about spirituality and the metaphysical, and it’s more abstract that way—about the process of investigating and being curious about different ways we process and think about death and the afterlife, or lack thereof.”

Warhol was raised in a devout Byzantine Catholic family, where Sundays were reserved for church and a reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper hung in the hall of his childhood home. (The exhibition features one of Warhol’s own reproductions of the painting, shown in black light to offer a different view of his Catholic upbringing.) From his religion, Moore says, Warhol developed a sense that the comforts of this world are ephemeral—a notion that is bound up in the Vanitas tradition and the paintings it inspired.

“They are these reminders that if we get too caught up in the pleasures of today, we’re going to be disappointed, because they’ll pass,” Moore says.

Wading into the Dark

Warhol was made acutely aware of life’s fleeting nature when he survived an assassination attempt in June 1968 that left him scarred and forced him to wear a surgical corset for the rest of his life. Several of his hand-dyed corsets are included in Vanitas. But even before 1968, his art revealed a preoccupation with death and its implications, Morgan notes.

In 1963’s White Burning Car III, part of Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” series, he repeated the silkscreened image of an upturned car, engulfed in flames following a deadly high-speed crash. In Foot and Tire, a nearly 7-by-12-foot silkscreen focuses on a haunting image cropped from another accident, showing only a lone foot crushed beneath a massive truck tire.

“People don’t necessarily expect Warhol’s work to have this kind of dark theme to it,” Morgan says, “but it’s actually quite common. There are a lot of dark themes and sarcasm and cynicism.”

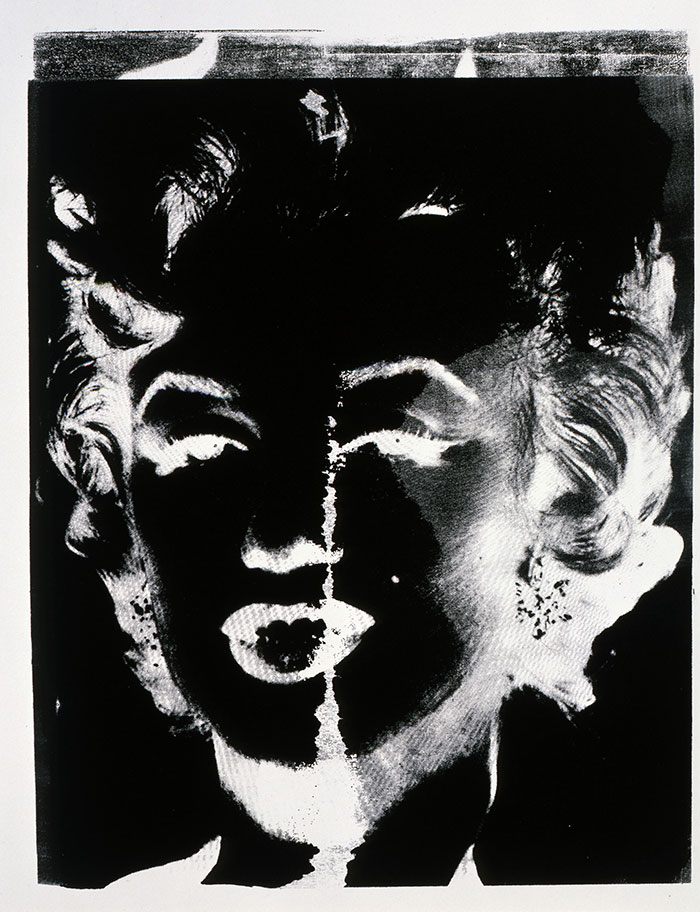

For those most familiar with Warhol’s Pop art—most notably his brightly colored depictions of celebrity—Vanitas offers a new lens through which to view his subjects and the way he saw them. A series of black-and-white screenprints of Marilyn Monroe, who died in 1962 at just 36, reverses the colors to appear like a photographic negative. Made in 1978, their eerie, ghostlike quality suggests Warhol’s fixation on the limits of fame, youth, and beauty in the face of life’s finitude, Morgan says.

“There’s always something about temporality that filters through his work—that sense of fragility,” she says.

“People don’t necessarily expect Warhol’s work to have this kind of dark theme to it, but it’s actually quite common. There are a lot of dark themes and sarcasm and cynicism.”

Amber Morgan, director of collections and exhibitions, The Andy Warhol Museum

Those concerns are made literal in a series of more than two dozen images of skulls that form one of the central motifs of Vanitas. Across sketches, paintings, photographs, and self-portraits, Warhol returned over and over to one of the most immediate and fundamental reminders that life can’t go on forever. His skulls capture Warhol’s ability to balance dark and light in his art. They represent death, of course, but they also bring out the artist’s humor, Morgan says: “The skulls almost look like they’re grinning.” For his part, Moore found them energizing and exciting; prints of Warhol’s skulls hung in his office when he worked at the museum.

Another series puts a spin on the Vanitas genre by depicting one of life’s most fleeting objects: the shadow. More than a dozen shadows appear in the exhibition, photographed by Warhol and then abstracted in a range of bold colors and screenprinted with diamond dust. They have a melancholy quality, Moore notes, and there’s something mysterious in the way they obscure their subject for the viewer. That seems fitting, considering what the Shadows suggest.

“They represent the thing that is maybe most temporal in the world,” Moore says. “A shadow is only a shadow until the light moves in a different direction—and then it disappears.”

The Only Inevitability

A small selection of Warhol’s film work adds another dimension to Vanitas, including Empire, an eight-hour-long silent marathon that offers a close study of the passage of time around the Empire State Building, viewed through a stationary camera.

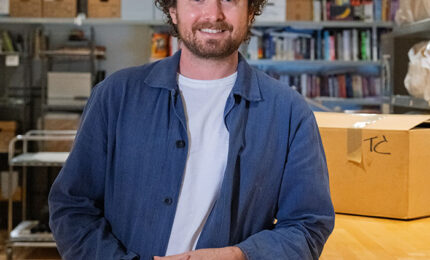

In 1965’s Outer and Inner Space, actor Edie Sedgwick discusses her ideas of space, the self, and personality—all in double screen, while she watches a recording of her own commentary. “It’s still viewed as the first masterpiece of video art,” says Matt Gray, the museum’s director of archives.

The 1963 film Sleep, meanwhile, spends five hours watching Warhol’s boyfriend and muse, John Giorno, in repose. Like much of the exhibition, it encourages consideration of the blurred line between life and death, Moore says.

“There’s this worshipful gaze—because Giorno was very beautiful—that Warhol had, but also he is laying there inert and it looks like he’s dead,” Moore notes. “There’s this idea of life and death toggling back and forth.”

Warhol’s contemplation—and even celebration—of life’s temporality draws a parallel across the centuries with the Dutch paintings he likely saw when he visited the Rijksmuseum in 1956. Vanitas Still Life, a 1650 painting by Jacques de Claeuw that features a skull and flowers scattered around a violin and crucifix, was on display during Warhol’s visit and has been brought to Pittsburgh for the exhibition. Along with a small collection of paintings from that era, it reminds visitors that Warhol’s work is part of a long lineage tangling with such weighty ideas.

“In the end, everything is temporary,” de Kloe says of the message that defined the Vanitas movement. “One can own the world, but even if one owns the world, don’t forget that you’ll die one day like everyone else.”

For Gray, that message doesn’t have to be morbid. “I see it as a way that we can all feel together,” he says. “We can all understand each other on the same level and relate in that way.”

To that end, the parts of the Time Capsule presented in vitrines throughout the exhibition are an intimate way to understand Warhol himself and how he approached the themes central to the Vanitas tradition in his own life. In the context of artworks contemplating the inevitability of death, Time Capsule-20—anti-aging creams, wig tape, and all—helps to demystify Warhol, Gray says.

“He is an iconic artist for a reason, but he and others like him get put on a pedestal where you can’t touch them,” Gray says. “These items bring him right back down to reality. And they reinforce what he was very well aware of: his own life and the fragility that came with it.”