Dyan Youpee has been working for years to return sacred objects and bodily remains of tribal ancestors to the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeast Montana—continuing the work that her father, Darrell “Curley” Youpee, began.

“There’s a multitude of situations and experiences in this work that confirm that he’s with me and guiding me more than when he was on Earth,” says Youpee, who buried her father in 2021. His death intensified Youpee’s commitment to fight for the rights of Native Americans to be buried in accordance with tribal customs.

In October 2023, Youpee brought home the remains of several individuals held by Carnegie Museum of Natural History through repatriation efforts with the museum under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). “All this work is to thank the ancestors who are not here,” says Youpee. “And it’s always, always about the ones yet to be born. This work is not about us. All of this legacy and work is an honor beyond anything I can imagine.”

Amy Covell-Murthy, archaeology collection manager who oversees repatriation and human remains policies for Carnegie Museum of Natural History, says the process with Fort Peck tribal members was emotional. “There were a lot of tears. It’s kind of a finalization, and I could breathe a big sigh of relief. These people are home now.”

“There has been an industrywide reckoning across natural history museums. We have all been looking at our own practices and how we’ve contributed to that and how we can play a role in addressing those issues.”

–Gretchen Baker, Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Natural history museums across the United States are known for their immense collections of the world’s wonders. And among the dinosaur skeletons, dioramas, and rare Earth gems, visitors are likely to come across displays that contain human remains. From the mummified body of a person to a human skull, set of bones, or teeth, most remains were taken without the consent of the individual. Now, museums are coming to terms with how these human remains ended up in their collections—and what to do about it.

“There has been an industrywide reckoning across natural history museums,” says Gretchen Baker, Daniel G. and Carole L. Kamin Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History and Vice President of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. “We have all been looking at our own practices and how we’ve contributed to that and how we can play a role in addressing those issues.”

Youpee is the cultural resources department director, Tribal Historic Preservation Program, and curator of the Fort Peck Tribal Museum and archive repository. From a young age, she learned by watching her father advocate for their ancestors.

“Because I breathe this type of work, and I’ve been prepared for this mentally, emotionally, and spiritually, I know that if I’m repeating some of the things that my dad has been saying for 20-plus years, then there has to be some change,” Youpee says. “There has to be some collaboration and being able to encourage institutions to make internal policy changes.”

Inheriting a Complex Issue

Museums are facing increased public scrutiny over their handling of human remains, and Carnegie Museum of Natural History is no exception.

“It’s become an institutional priority,” Baker says. “It’s not just the behind-the-scenes, but in every way that we carry out our mission. Removing the human remains from public display is part of this broader question of how we ethically and equitably care for the remains of individuals that are in our care.”

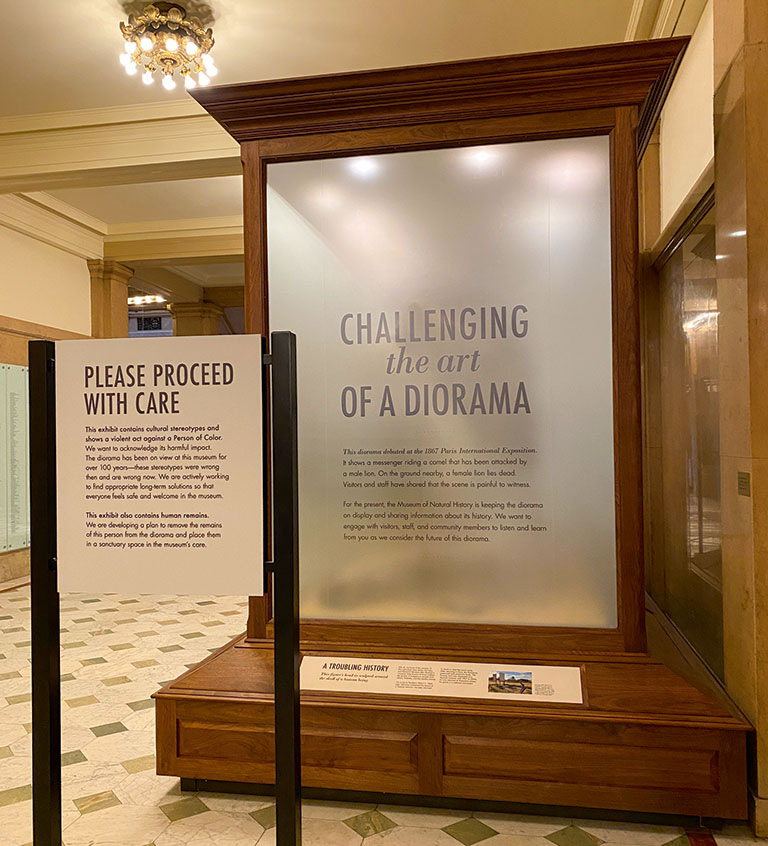

Last year, Carnegie Museum of Natural History removed all human remains from view, including those in the Hall of Ancient Egypt and its Lion Attacking a Dromedary diorama, which had been on display at various locations around the museum for more than a century. Museum researchers were aware that the diorama contained human teeth, but an X-ray scan in 2016 revealed it contained a human skull.

The removal of the person’s skull was guided by the museum’s new policy defining how human remains are to be handled, displayed, and returned. The policy was approved by the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh Board of Trustees on August 30, 2023, and went into effect immediately.

“The idea that human remains are people is kind of hard for some science-minded individuals to grasp,” says Covell-Murthy. “When we start talking about how we’re dealing with actual human bodies, people kind of change their tune.”

Museums everywhere are grappling with what to do with the remains of tens of thousands of people who ended up in their displays or storage cabinets. Smithsonian Institution, which holds one of the largest collections of human remains in the world from some 30,000 individuals, last year established a Human Remains Task Force to write guidelines on “the ethical acquisition, care, use, and return of human remains.” The American Museum of Natural History in New York City, which has the remains of 12,000 people, also announced in October that the museum would remove human remains from public displays.

Photo: Robert Jones

Photo: Robert Jones“The idea that human remains are people is kind of hard for some science-minded individuals to grasp. When we start talking about how we’re dealing with actual human bodies, people kind of change their tune.”

–Amy Covell-Murthy, archaeology collection manager for Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Covell-Murthy estimates that the remains of about 800 individuals—mostly of Native American descent—are currently in the care of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. She and other staff members have been actively working to repatriate these remains. Since NAGPRA was enacted in 1990, the museum has returned the remains of over 100 individuals to their descendant communities.

In 2009, Covell-Murthy began to review how human remains in the museum’s collections were being treated. “Human remains were once part of living, breathing people with cultural and familial ties, and should not be equated with the other material in a natural history collection,” she says.

NAGPRA—which was instituted by Congress to protect and return Native American human remains, sacred and funerary objects, and objects of cultural significance—provides guidelines for how to operate with human remains originating in the U.S. But many museums have been slow to return items, and in January, new federal regulations went into effect that were designed to hasten the process. However, there is no international law that governs their return outside the country, “so internal policy is the best way to ensure that you’re treating every situation and person equitably,” Covell-Murthy notes.

Covell-Murthy spent more than a year leading a cross-departmental group of 22 museum employees and stakeholders to create its policy.

The first step was to define what constitutes human remains and figure out exactly what the institution had in its collections. Even the mannequins in the cultural halls needed to be considered, as they were modeled after actual people who gave permission to be used in an exhibit.

“You have to ask yourself what constitutes human remains in your collection,” Covell-Murthy explains. “Does hair, because it’s freely shed, still count as being human remains? Where do you put human beings on the evolutionary time scale? … We had to answer all of these questions as an institution.”

The Critical Issue of Consent

Seven years ago, Carnegie Museum of Natural History researchers discovered that Lion Attacking a Dromedary contained an actual human skull within the sculpted head of its main figure

The diorama, featuring a courier atop a one-humped camel being attacked by two Barbary lions, was made by French taxidermist Édouard Verreaux for the Paris Exposition of 1867. It was purchased by the American Museum of Natural History in New York, but was taken off display for being “too strong on theatrics” and was set to be destroyed until Andrew Carnegie stepped in to purchase the exhibit for $50 in 1898.

Covell-Murthy notes there are many problems with the diorama, starting with its misrepresentation of North African culture and attire. But at the top of the list was the fact that it contained an actual human skull.

As it turns out, Verreaux and his brother Jules weren’t exactly doing things by-the-book, and they infamously robbed graves in the 1800s during trips to Africa. The family business trafficked primarily in exotic birds and animals, and brought more than 130,000 specimens back to France after an 1818 trip to Africa, including human skulls.

The skull in Lion Attacking a Dromedary is likely one of those skulls, but it was never documented as being used to create the display.

“That diorama became the flare point for our discussions about representations of different communities on display, how we represent them, as well as human remains,” Baker says.

The issue even involves classroom teaching tools. Decades ago, the museum purchased a classroom skeleton from a scientific education company, only to discover years later that it was comprised of the actual remains of an unidentified woman from India. Many skeletons still used in classrooms are from human beings from India or China who were sold by families to scientific companies, often because the families needed money. During that time, the bone trade also involved human skulls. Dental students were even encouraged to purchase human skulls to practice their dental procedures.

“The relationships that we have with living people are more important than an object on a shelf.”

–Kristina Gaugler, anthropology collection manager for Carnegie Museum of Natural History

These individuals hadn’t given their consent for their bodies to be used in these ways, and informed consent is at the core of Carnegie Museums’ new policy on human remains in its collections. Human remains will no longer be exhibited without informed consent from the deceased individual, their living relatives, descendent communities, or ethical stakeholders.

Doing right by Indigenous communities involves relationship building and learning each nation’s practices for keeping their sacred objects and remains, says Kristina Gaugler, anthropology collection manager, who works closely with Covell-Murthy in the section of anthropology.

“The relationships that we have with living people are more important than an object on a shelf,” Gaugler says.

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua FranzosMuseum staff also are changing how remains are cared for, including keeping them in their original coffins and bringing objects associated with the deceased people in close proximity to them, “to be in contact with the things that they were intentionally placed with,” says Gaugler.

“We are hoping to complete a sanctuary space for human remains that aren’t able to be repatriated as quickly as we’d like,” she adds.

Because the human beings whose remains ended up in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s care are being handled in new ways, such as being reunited with their belongings in burial boxes as close to being in the ground as possible, the work of collections managers has become that much more challenging.

It’s particularly challenging for museums that store other materials—ceramics, for example—together. It takes an immense amount of staff time to sort through, catalog, and reorganize collections that include tens of thousands of artifacts—human remains mixed among them. Covell-Murthy had a head start because of forward-thinking predecessors like Verna Cowan, a curator in the 1990s who anticipated NAGPRA and worked diligently to reorganize the archaeological collection accordingly.

For example, the museum’s ethnographic artifacts are organized by cultural grouping, rather than item type, which recognizes a more holistic picture of the artifacts.

“Some things are easier for me because I had really thoughtful predecessors,” Covell-Murthy says.

‘Egypt on the Nile’

The museum’s human remains policy goes beyond meeting the federal requirements of NAGPRA to consider the ethics of other groups, including people from ancient Egypt.

Andrew Carnegie was fascinated with Egypt, and his first purchase for the museum was the coffin and body of an unnamed Chantress of Amun. The Museum of Natural History now stewards around 5,000 objects from ancient Egypt and the mummified remains of 17 individuals.

“Prior to 1835, you used to be able to just buy whatever you wanted in Egypt if you were rich—including people,” says Lisa Haney, the museum’s Egyptologist and assistant curator of the future exhibition Egypt on the Nile. “Then in 1835, the Egyptian government banned the export of mummified human remains. So people started parting them out, because it would be easier to smuggle part of a mummified person back with you than the whole thing.”

An important first step in assessing how to care for these human remains is acknowledging why and how they came into the care of the museum in the first place. The collecting of ancient Egyptian human remains by European and American institutions increased dramatically in the 19th century, but these trends were part of a longer history of “cabinets of curiosities fueled by imperialism, Enlightenment thinking, and, later, the development of the pseudosciences of phrenology and craniometry,” according to a forthcoming research paper by Haney. Institutions such as Carnegie Museum of Natural History are grappling with that history as they determine how best to care for the remains moving forward.

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua FranzosMuseum staff removed the last of the human remains on view in Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt when it closed last summer. Haney has been working with museum staff to replace that exhibition with Egypt on the Nile, which will focus on the connection between ancient Egyptians and the natural environment of the Nile Valley.

“We’re really trying to bring the exhibition into the moment and reflect the material in our care as research that’s going on behind the scenes,” Haney says. This deliberate shift away from the ways the museum displayed and spoke about ancient Egypt in the past includes removing mummified remains from public view entirely.

In the meantime, a temporary exhibition called The Stories We Keep focuses on museum conservation work. Some Egyptian artifacts are on display while others are being actively worked on in a visible conservation lab.

Working with the Descendants

Western Pennsylvania has no habitable, federally recognized tribal land in the state, as tribal nations were forcibly removed from the region. The last Indigenous tribe in the region, the Seneca Nation of Indians, were displaced to New York by eminent domain claimed by the Army Corps of Engineers to build the Kinzua Dam.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History was a repository for the State Museum of Pennsylvania until the early 1990s. Most of the remains in the museum’s care were excavated prior to laws preventing the destruction of historically significant sites. Because of that, the museum has a large number of human remains from the upper Ohio Valley. Repatriation has been difficult, in part because Native peoples migrated through Pennsylvania multiple times throughout their history, bringing with them varying oral traditions.

Photo: Joshua Franzos

Photo: Joshua FranzosLab testing can help identify bones, but remains can’t be displayed or used for destructive analysis without consent. The museum is working with groups who are connected to this region to help match the known geographic origins of each set of human remains to a present-day tribe. This process and the decisions that come out of it are being determined by the tribes, and the museum continues to repatriate and help rebury human remains from its collection.

This is an urgent issue for Indigenous communities, and Dyan Youpee is among a growing number of Native people showing up in museum spaces to demand their ancestors be returned.

Youpee says Carnegie Museum of Natural History has been quick to return tribal remains to their descendants, an experience she adds is not often the case with many other museums. She says Covell-Murthy’s “cultural competency” has been vital in building their working partnership to repatriate the remains of Youpee’s ancestors.

“It’s really hard to teach cultural competency when people haven’t been exposed or worked with tribes on a daily basis,” Youpee says. “So it was really helpful that she understood and that she had a team that understood.”

Youpee says she intentionally brings museum workers into the repatriation experience to help teach non-Native people the importance of tribal objects and funerary practices for the tribes she represents.

“I can’t quantify the amount of sacredness in a cup. It’s intangible,” Youpee says. “But by showing them, by bringing their faces right to what I’m looking at and being a part of talking to objects, talking to our ancestral remains, and even inviting them to witness the reburial … it helps them to work with the next tribe, and then the next tribe.”