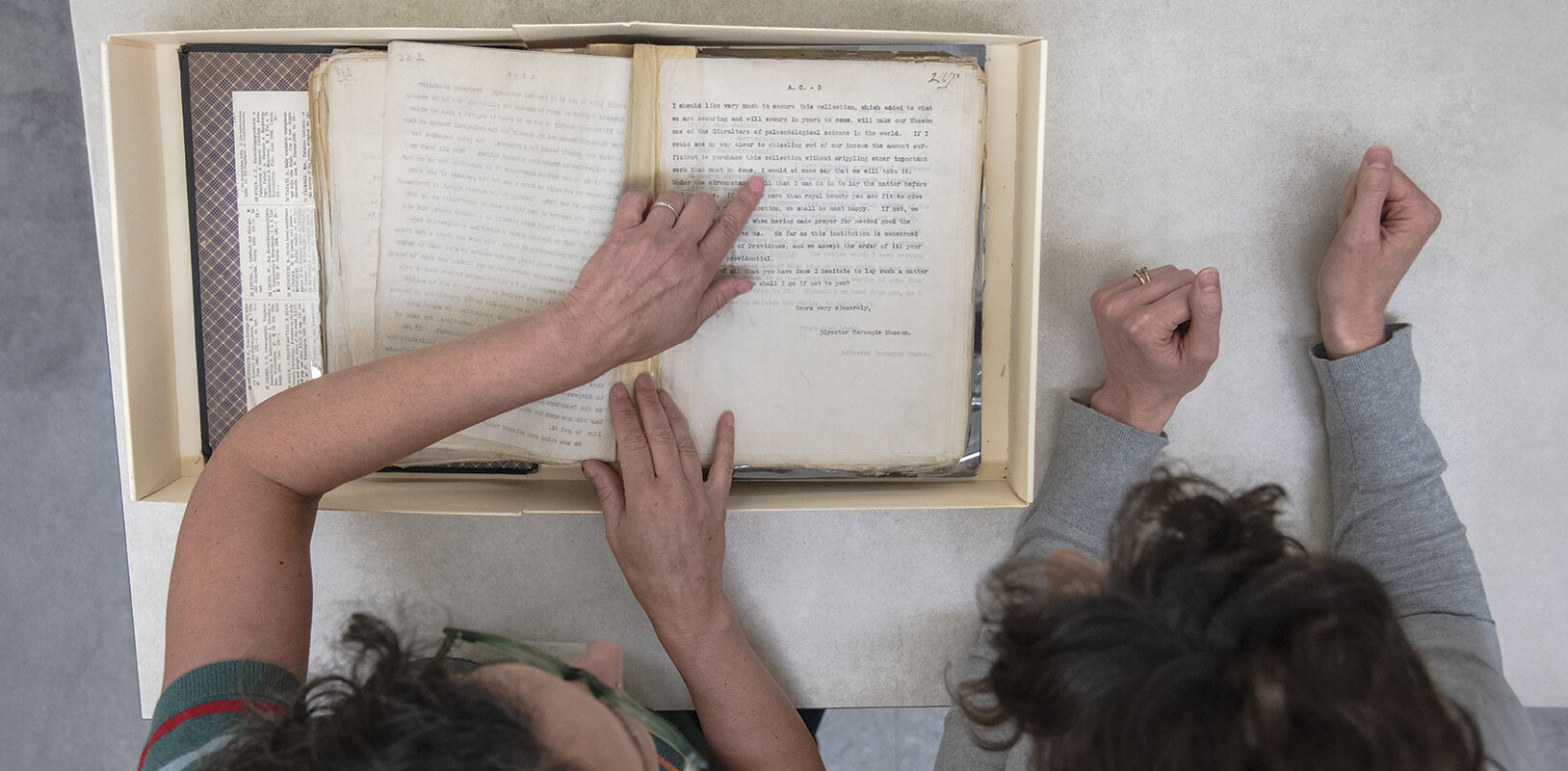

When science historian Ilja Nieuwland visited Carnegie Museum of Natural History on a research trip a decade ago, he was dismayed. He’d come from the Netherlands while working on American Dinosaur Abroad, his book about the plaster casts of Diplodocus carnegii that populated European museums in the early 20th century. Leafing through an archive of letters written by William J. Holland, the museum’s second and longest-tenured director, Nieuwland encountered a wellspring of information, not only about the history of the famed dinosaur that came to be known as “Dippy,” but also about the entire field of early American paleontology. More than 100 years on, though, the pages of the Holland letterbooks were in desperate need of conservation.

The situation was “dire,” Nieuwland says. The onion-skin paper on which the letters were written had become brittle, degraded by the acid in typewriter ink; he had to wear gloves to avoid further damage. Coal-dusted fingerprints marred the correspondence, letters were fading away, and covers were falling off some of the bound volumes. For a researcher eager to pore through a collection of more than 15,000 pages documenting the origins of the museum and its most storied artifacts, the only clue to guide the process was a handwritten index.

The archive—a vast record of Holland’s outgoing correspondence—offered Nieuwland a unique window into the daily activities of a natural history museum at the turn of the century.

“Holland was a notorious micromanager,” Nieuwland says. “This causes the correspondences to be inordinately broad and granular at the same time.”

Photo: John Schisler

Photo: John SchislerWithout conservation, he knew all that history might be lost. Nieuwland discussed his concerns with Paul Brinkman, a fellow paleontologist who shared his misgivings. Worried about the archive’s fate, Brinkman wrote to museum staff, urging them to preserve the letters. “Digitization of the Holland correspondence would be an invaluable contribution to the history of American museum science,” he wrote.

Over the past two years, the museum’s librarian, an archivist, and its curators have carried out that much-anticipated feat by conserving and digitizing the contents of Holland’s letters so they can be studied for generations to come. With the help of a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), the archive is better protected and more easily accessible in digital form. It can now serve as a vibrant resource for exploring the early development of the Museum of Natural History and its contemporaries.

“Museums can sometimes seem like their inner workings are inaccessible: You go, you see what’s on the floor, and that’s the museum,” says Lisa Haney, a curator at the museum and the project’s leader. “These letters offer our visitors and other interested people—not just those located here in Pittsburgh—the chance to see what goes on behind the scenes and how this very museum was created.”

A First-Person History

Carnegie Institute was still in its infancy when Holland, a naturalist and chancellor at the University of Pittsburgh, was tapped to oversee the museum in 1898. With Andrew Carnegie’s largesse, he set out to make the institution “one of the most famous as well as one of the most potent for the good of its class,” as he wrote to a colleague.

The archive, which spans 1896 to 1913, tells the story of Holland’s quest, in his own words. Its contents portray him navigating the process of building an American museum’s collection at a time when there was no blueprint for doing so. In letters to partners, researchers, and Carnegie himself, Holland pondered the role of a director in shaping a collection, respectfully requested additional funding to carry out his vision, and described the discovery of Dippy, the acquisition of the Bayet fossil collection, which still accounts for the bulk of the paleontology department, and the arrival of a 4,000-year-old Egyptian funerary boat—all of which still inspire visitors today.

“It’s striking seeing the museum find its identity and figuring out how it wanted to work,” says curator Deirdre Smith.

Despite the wealth of insight contained in the archive, its use was limited to those who could access it in person—and its condition raised questions about its future. The museum secured the IMLS grant in 2023 with three goals in mind: conserving the letters, creating a searchable digital repository, and expanding access to students, researchers, and museum professionals in Pittsburgh and beyond. As Haney says, the letters hold the answers to a range of important questions about the museum’s history and its place in the development of natural history museums writ large. “In order for us to be able to explore those questions, we first had to complete this project,” she says.

Photo: John Schisler

Photo: John SchislerLibrary Manager Marie Corrado sent the archive to Philadelphia’s Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts, where every page was digitized and carefully checked for any necessary mending or cleaning to ensure long-term preservation. The staff at the center built conservation-grade archival boxes to hold the volumes and made high-resolution digital scans of each page so they can be viewed without any further physical handling. Project archivist Hanna Dahlstrom then spent the past year and a half developing a digital database that will allow anyone to search for letters relevant to their interests.

“These letters offer our visitors and other interested people—not just those located here in Pittsburgh—the chance to see what goes on behind the scenes and how this very museum was created.”

Lisa Haney, Curator

Now safely preserved, Holland’s letters are ready to be studied widely. Last fall, Smith, who is also a teaching assistant professor of museum studies at the University of Pittsburgh, incorporated them into her course Inside the Museum, which examines behind-the-scenes museum practices. Students reviewed curated letters from the archive that focused on fossil excavation, Egyptology, and the museum’s Costa Rican collection, then wrote about their own interpretations of the letters. “It was revelatory for them to read,” Smith says.

Drawn in by the intimate and engaging nature of personal correspondence, Smith’s students had the opportunity to ponder the context in which Holland and his contemporaries operated and the complexity of their work. As Pitt senior Casey Withers wrote, reviewing a series of letters in which Holland rejected donations to the museum’s collection “provide[d] a glimpse into the personality of both the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and the second director himself.”

Grand Ambitions

The letters reveal the grand aspirations shared by Holland and his wealthy benefactor and the expansive nature of their collaboration.

In some, Holland contemplated why museums exist and what this one should explore. “Chemistry, mineralogy, geology, botany, entomology, ornithology—all the ologies are represented here,” he wrote to a colleague in 1901.

In other letters, he offered instruction on fieldwork, including an August 1899 missive in which he celebrated Dippy’s discovery in Wyoming and urged excavators to keep searching for the rest of its bones. “They have not trailed very far away,” he wrote. “There was not very much current in that pond where old Diplodocus lay down and died.”

“[Holland] was involved in everything—every little detail of every section and everything that everyone did.”

Marie Corrado, Carnegie Museum of Natural History Library Manager

The archive offers a window into Holland’s central role in the museum’s development. In his letters, he outlined his ideal staffing structure and contemplated the challenge of securing the most talented experts. But he also tended to the minutiae of organizing a museum, all the way down to the cabinets being built to house its collections.

“He was involved in everything—every little detail of every section and everything that everyone did,” says Corrado.

In a letter to Carnegie in July 1901, Holland called himself a “committee of one” in addressing the plan and scope for the museum that was to be Carnegie’s “chief monument.” The museum had “a future of great hope and promise,” he said, owing to “the magnificent generosity” of its founder.

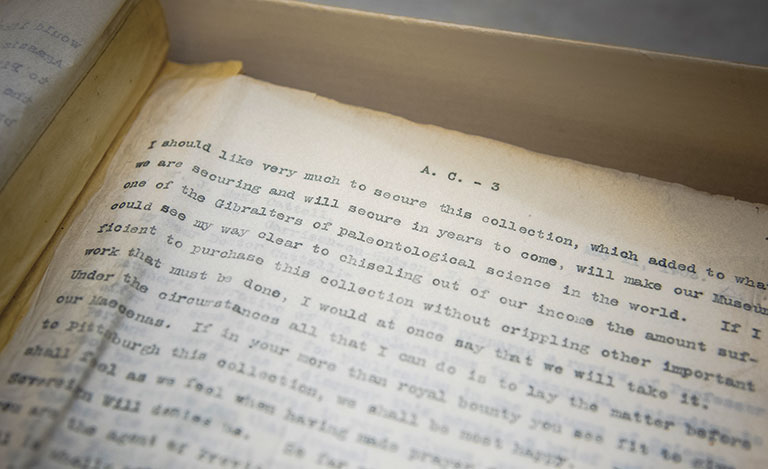

Holland wasn’t shy about leaning on that generosity, pushing Carnegie to set aside $100,000 (equivalent to about $3.5 million today) to support the publication of scientific research that could compete with other illustrious museums, or reminding his financier that institutions with greater resources were snapping up collections he was pained to lose. In May 1903, he asked Carnegie for $25,000 to secure the Bayet fossil collection, which had been put up for sale in Europe by the Baron de Bayet, secretary to the cabinet of Leopold II of Belgium. Facing competition from museums around Europe and the United States, Holland immediately booked passage on a ship to Europe to complete the deal. The price tag to acquire the massive collection—130,000 fossilized invertebrate and vertebrate specimens that go back hundreds of millions of years—was larger than the entire 1903 budget for all art and natural history acquisitions combined. But Holland assured Carnegie that it was a worthwhile investment, one that would “make our museum one of the Gibraltars of paleontological science in the world.”

Connecting to the Past

Read as a whole, the letters suggest a man who shrewdly navigated the museum’s development and the acquisition of the collections that came to define it, Smith says. Holland could be “curt and sassy, at times,” she says, including when he found himself unhappy with an employee or donor. But he was always focused on the task at hand.

“Holland was a go-getter. If he wanted something to be done he would get it done,” Dahlstrom says. “He didn’t seem like a very soft-spoken guy. He was straight to the point. If he had a complaint, he’d write you 10 pages about why you upset him.”

Holland often wrote to the heads of the country’s railway companies asking for free passage of fossils as the museum’s collection expanded, then thanked them by sending along a book he’d written about his favorite subject: butterflies. An accomplished lepidopterist who published influential books on butterflies and moths, he found that leading the museum demanded he become something of a Renaissance man, capable of demonstrating expertise well beyond his subject of choice.

Photo: John Schisler

Photo: John Schisler“The immense amount of work connected with an infinitude of small details, all of which [require] more or less exact knowledge, is something that at moments appears almost appalling,” Holland wrote. “Every scrap of information which a man possesses is sooner or later brought into play.”

For the curators and archivists who have led the effort to preserve the letters, the insight they offer on the museum’s history is a gift to be shared as widely as possible—and they intend to make the digital archive accessible to the public in the near future.

A selection of letters will be on display in the museum beginning November 8 as part of the exhibition The Stories We Keep: Bringing the World to Pittsburgh. And Smith plans to dive back into the archive with a new class of students this fall, further extending the letters’ reach.

“Being able to get more curious and be more empathic about the museum actors of the past is really important,” she says.

Museum staff have always been able to access the archive, but Smith is eager to see more people engage with the letters moving forward, finding “so many unexpected connections and benefits” along the way. That vision is closely aligned with Holland’s own, as he expressed in a letter to Carnegie in 1901.

“There are vast territories of knowledge which yet remain in this little world of ours to be explored,” Holland wrote, “and the institution which systematically addresses itself to the work of extending the boundaries of human knowledge covers itself with lustre.”