Jessica Beck needed only a few minutes in Devan Shimoyama’s studio to know she wanted to offer him a show at The Andy Warhol Museum. “Immediately I thought, ‘These works are stunning!’” says Beck, the Milton Fine Curator of Art at The Warhol, referencing the artist’s work from 2016, including the mythical self-portrait He Loves Me (Not). “The surfaces of his paintings are so subtle that it looks like they were painted with feathers. He has this ability to capture the softness of skin and flesh.”

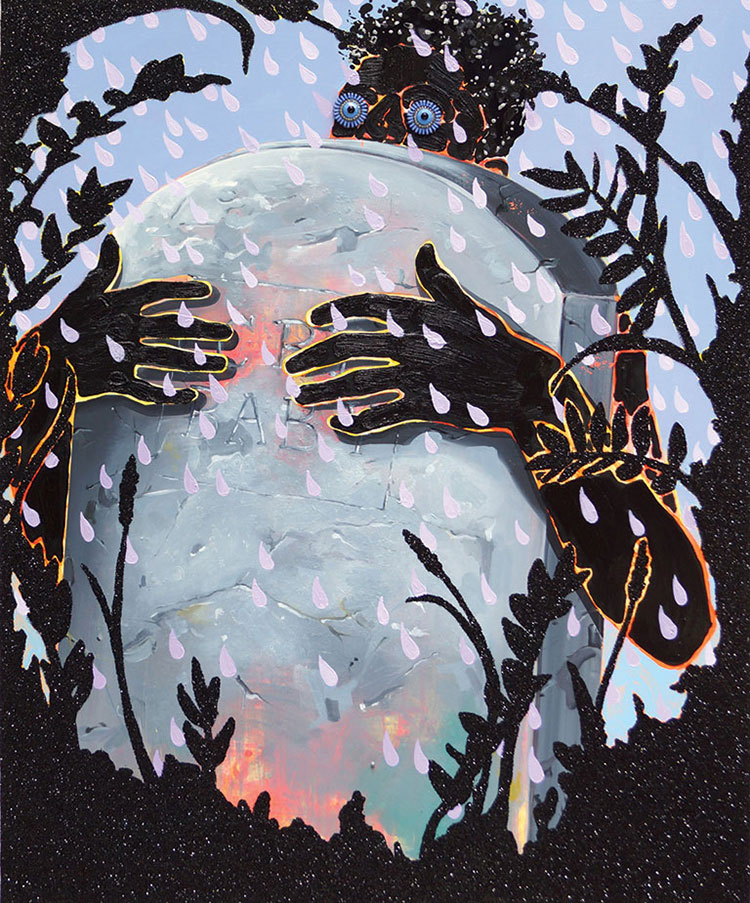

Shimoyama’s paintings crackle with color and dazzle as light glints off glitter and rhinestones. Yet the narrative under his lush surfaces is complex and tender. Tears cover the background or spring from the surface as collages of crystals bedazzle lone figures searching for safety in a world hostile to black, queer bodies.

Devan Shimoyama, He Loves Me (Not), 2016, Karyn and Charles Bendit Collection

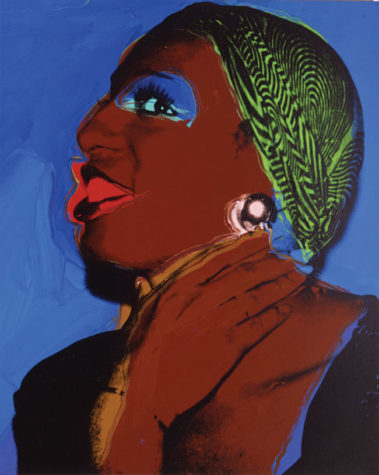

This twining of glamour and struggle immediately reminded Beck of one of Warhol’s lesser-known bodies of work, Ladies and Gentlemen. Commissioned by Italian collector Luciano Anselmino and completed in 1975, this series of portraits depicts black and Latino transgender women and drag queens. While the 348 paintings Warhol produced show perfection, the preparatory Polaroids reveal markers of poverty: a missing tooth or ill-fitting, cheap wigs.

Opening on October 13, Devan Shimoyama: Cry, Baby will mark the artist’s first solo museum exhibition and coincide with a fourth-floor reinstallation of The Warhol’s permanent collection of paintings, prints, and source photos from Ladies and Gentlemen. One of Shimoyama’s portraits of Miami drag queens will be displayed in dialogue with Warhol’s series, connecting the two bodies of work.

Andy Warhol, Ladies and Gentlemen (Wilhelmina Ross), 1975, The Andy Warhol Museum, © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

At age 28, Shimoyama has been pursing art with singular focus since his junior year in college. Growing up in northeast Philadelphia, he took drawing classes, but wasn’t sure how artists forged sustainable careers. So, instead, he started out at Pennsylvania State University as a life science major.

“I literally woke up one day and changed my major to art,” he recalls. “I didn’t really think about it too much.” In addition to taking a more-than-full course load so he could graduate on time, he created a club and traveled to New York City to learn about the industry.

In 2014, Shimoyama received his MFA in painting and printmaking from Yale University and immediately moved to Pittsburgh to teach at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU). “It was rapid-fire. It’s been such a period of exponential growth,” he says. “Pittsburgh is where I figured out who I am as an artist.”

At CMU, he notes, he’s surrounded by people who work in other mediums. “It forces me to be even more of a painter. It makes me even more different.” In fact, much of Shimoyama’s work had been forged in relative isolation. While at Penn State, he didn’t feel at home in the LGBTQ+ clubs, spaces that seemed “largely white.” His mother, who had him at age 16, is a lesbian, so he didn’t share the same experiences as many of his gay peers who weren’t accepted by their families.

Because he was the only person of color in the painting department at Penn State, he relied on his own body as a model to work out how to paint non-white skin. Gradually these self-portraits became more abstract, eyes and lips replaced with collaged eyes from fashion magazines or photos of the women in his family. “The eyes represent the maternal energy that surrounded me growing up,” he says. “I have always been around strong women of color: my mom, aunt, and grandmother.”

Devan Shimoyama, He Lies, He Cries, 2016, Courtesy of Joyce Varvatos and the artist

Shimoyama’s interest in religion, myth, comic books, and science fiction as represented by people of color, including Octavia Butler, came together in these early paintings. “I was creating this shamanistic figure who is searching for his origins,” he explains. “He is alone, looking for others like him, exposing moments of magic, and opening up portals in the night sky.” The figure is often depicted with a glittery snake, a symbol of healing and fertility in some African religions. “In Western culture, the snake is conniving, but it used to be beautiful and a companion to women,” he says. “The figure in my paintings and the snake have an understanding of one another because they are both misunderstood.”

Accessing the Magic

Around 2016, Shimoyama’s work shifted from depicting a mythical space to exploring the real space of the barbershop. While traditionally a place of togetherness and safety in many black communities, the barbershop isn’t exactly a welcoming, comfortable place for queer black men. At times, Shimoyama has chosen to cut his own hair, as do many of the figures in his paintings. In Michael, painted this year, a man stands in a purple bathroom and takes a razor to his silver hair. Shirtless, his torso is comprised of flecks of color resembling a field of wildflowers.

Devan Shimoyama, Michael, 2018, Courtesy of Richard Gerrig, Timothy Peterson and the artist

“These are fraught spaces for people who don’t perform masculinity in an accepted way,” says Rickey Laurentiis, creative writing fellow at the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics at the University of Pittsburgh. Laurentiis, who contributed an essay for the show’s catalogue, says a young boy’s first haircuts can be traumatic. “Someone is coming at you with mechanized razors and you are told: ‘Don’t cry, be a big boy, be a little man.’ The barbershop is a place where masculinity intensifies around itself.”

Shimoyama transforms the barbershop into a colorful, queer utopia, where boys are free to cry as caring feminine hands clip their hair. His newest series of portraits star drag queens of color. He noticed that even though RuPaul’s Drag Race is making drag more mainstream, black and Latino drag queens are still marginalized. “[RuPaul’s Drag Race] reflects the real world,” he says. “White drag queens are celebrated more.” During a July residency in Miami, he followed performers, talking with them and watching them get ready in order to celebrate them in “superhero portraits.” “I am making fan art,” he explains.

“I want my work to be dazzling. I want it to change when you walk across it and be alive.”

– Devan Shimoyama

Shimoyama has another connection to drag queens: He often shops in the same stores as them for the rhinestones and glitter that enrich the surfaces of his paintings. Shimoyama tends to work on four paintings at a time while listening to music or epic fantasy novels. “While painting, I am thinking about color and light,” he says. “I am thinking about that dazzling sensation when a drag queen is performing and the spotlight glints off her sequins. It’s magic.” He hopes to recreate that sensation for the viewer. “I want my work to be dazzling. I want it to change when you walk across it and be alive.” Sometimes he even adds feathers that undulate when viewers walk by.

In the materials Shimoyama uses, Laurentiis sees a powerful argument for celebrating gay culture. While feathers, fashion magazines, and glitter are associated with gay culture, they are largely derided in the art world as childish or cheap materials. “Black queer subjectivity is already seen as flamboyant because it’s non-normative,” says Laurentiis. “Shimoyama reclaims flamboyancy by using the very materials used to debase it.” While a young gay man might be bullied for being “limp-wristed” or walking with a “swish,” Shimoyama embraces in his paintings feminine poses on masculine bodies as something beautiful.

Laurentiis uses the term “the black ecstatic” to describe this flamboyancy. “It’s about seeing your blackness in a new way because you come into contact with something other or beyond language: the divine, or history, or queerness.” Shimoyama relates these moments of transformation to magic: “Magic is constantly floating around us, and some people have access to making it tangible and some people are hardened and don’t want access to it,” he says. For him, magic is linked both to blackness and to queerness: two things that can create a change or shift when they appear in a room.

Devan Shimoyama, Cry, Baby, 2016, Courtesy of Howard C. Eglit and the artist

To access this magic, Shimoyama notes, the walls of reified masculinity must come down. This is why tears—of sadness and also of resilience—figure so prominently in his work. “Crying was not something I saw men doing when I was growing up,” he says. “Black men always felt so pent up, using masculinity or anger to shield themselves.” He describes crying as a way to decompress, to let that energy go and relax. Many of his paintings create safe spaces in which boys can do just that. In Cry, Baby, a 2016 self-portrait, he anxiously clutches a large tombstone, eyes stretched wide open, as the sky sheds lavender tears.

“Cry, Baby is about taking vulnerability and using it as strength,” Beck says. “It’s a great name for the exhibition because it’s about permission: permission to cry, permission to be queer, permission to just be without any limitations.”

In Shimoyama’s barbershop paintings, the tears are no longer in the background. They’re three-dimensional crystals affixed to the figures’ faces. “The paintings’ provocation is to take a moment of black queer abjection and reclaim it for beauty,” Laurentiis says. “He turns the tears into diamonds, into capital. He makes them into wealth.”

Dealing with the darkness

Cry, Baby the exhibition will include 36 paintings and objects, including a pair of sculptures Shimoyama created in response to the slayings of two black children. A swing is covered in cloth flowers for Tamir Rice, who was shot on a playground, and a hoodie turned into a feathered robe for Trayvon Martin, who was wearing the popular garment when he was killed.

“There have to be other ways of dealing with that darkness that don’t just re-present it,” says Shimoyama. He looks to the iconography of urban memorials—flowers and stuffed animals—left at sites of shootings as he takes objects that are emblematic of each tragedy and transforms them into radiant symbols of empowerment.

“Cry, Baby is about taking vulnerability and using it as strength. It’s a great name for the exhibition because it’s about permission: permission to cry, permission to be queer, permission to just be without any limitations.”

– Jessica Beck, The Warhol’s Milton Fine Curator of Art

Beck hopes the exhibition will spark meaningful discourse. “The Warhol is a place where dialogues can happen around race, identity, and pop culture because they are a part of Warhol’s tradition,” she says. Programs designed to help forward this conversation include artist residencies with renowned New York-based artist Rashaad Newsome and The Black Joy Project creator Kleaver Cruz, poetry readings, and dance parties.

Devan Shimoyama, For Tamir III, 2018, Courtesy of the artist

Shimoyama also finds connections between his work and Warhol’s, particularly their shared interest in fashion. “Growing up, Warhol was an artist that I knew, even though I didn’t know a lot of contemporary artists,” he says. Shimoyama says he discovered some of his greatest inspirations— contemporary artists of color Kerry James Marshall and Mickalene Thomas, as well as the visionary printmaker and poet of the early 19th century William Blake—later in life. “[Warhol] did so much that every artist is a product of him in some way—whether they like it or not.”

He also sees his own work as a departure from Warhol, because he doesn’t see the same deep reverence he has for drag queens in Warhol’s work. Shimoyama says the way in which Warhol treated his sitters was “messy” because he didn’t use their names when he showed the work—a request of Anselmino as part of the commission. Nor were they well-compensated for their time. Researchers have recently matched the paintings with the sitters’ names using payment receipts in Warhol’s archives. This marks the first time the portraits will be shown at The Warhol along with their subjects’ names.

“Warhol was really at the beginning of these conversations around identity,” Beck says—conversations Shimoyama continues in his own portraits.

“The most important thing is just seeing Devan’s images,” says Beck. “It’s just important for people to know that his work tells a valuable story of acceptance: that it is okay to be vulnerable, to embody both masculine and feminine traits, to be young, queer, and want to live life and be free from shame.”

Generous support of Devan Shimoyama: Cry, Baby is provided by the Quentin and Evelyn T. Cunningham Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation; The Fine Foundation; Arts, Equity, & Education Fund; Karen and Jim Johnson; De Buck Gallery; and Stacy and Samuel Freeman.