Farhad Moshiri spent much of his childhood watching movies in Shiraz, Iran, where his father owned a chain of cinemas. One of his earliest movie memories is a Dracula film—it made 3-year-old Moshiri scream and cry so loudly that an usher walked him home. That early trauma gave way to his love for all kinds of movies, from horror to Bollywood to American westerns.

The rest of the audience could be a tough crowd, ripping up the seats if they didn’t like a movie. Art-house international films were particularly unpopular. Moshiri’s father had to hire an upholsterer to repair the seat damage between showings. But there was little trouble with westerns. The audience sat rapt watching John Wayne spout his tough-guy lines in dubbed Farsi.

When Moshiri moved to the United States during the Iranian Revolution at age 15, the American cowboy followed him, first to boarding school in California and then to the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), where he studied art and filmmaking until his graduation in 1984.

His global perspective changed a lot through the turbulent ’80s, when the United States and Iran clashed over Cold War tensions. It showed in his artwork. Upon moving back to Iran in 1991, Moshiri began experimenting with images and materials from both cultures—from traditional Iranian handicrafts to modern kitsch, plucking images from cartoons, films, comic strips, and Persian antiquities, and phrases from soap operas and pop songs.

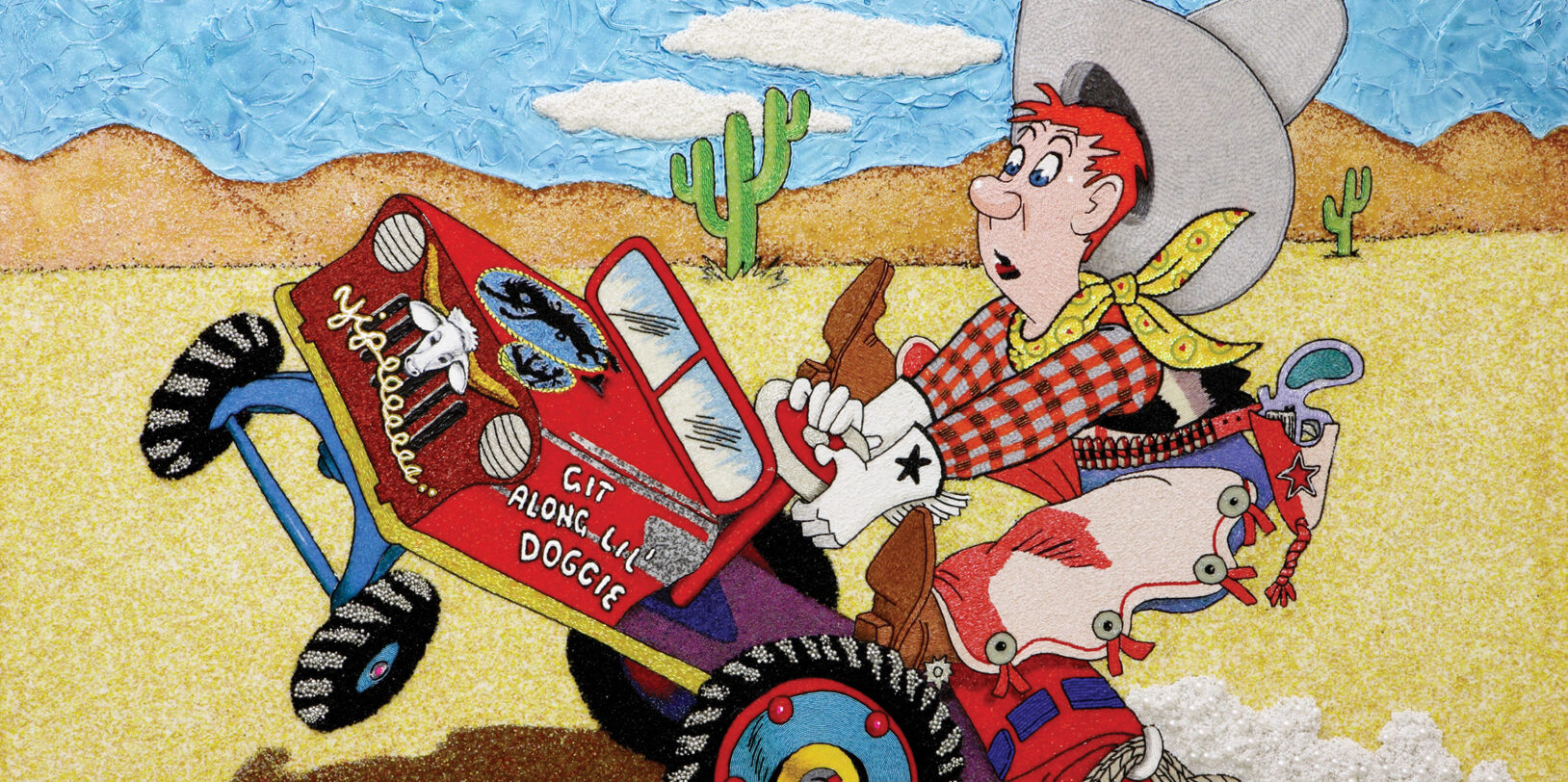

The artist will debut his first solo museum show, Farhad Moshiri: Go West, at The Andy Warhol Museum on October 13. Cowboy images abound. In Yipeeee (2009), a red-headed cowboy looks a bit like Howdy Doody as he struggles to control a red cart that reads, “Git Along Lil’ Doggie.” On the verge of tipping over, the cart sputters along on an empty desert landscape. The artwork is based on an American-made tin toy owned by the artist. In another work titled America (2010), Moshiri portrays a western saloon filled with cartoon characters caught up in a wild brawl. The madcap scene, like Yipeeee, is hand embroidered with glass beads, a hallmark of traditional Persian handicrafts.

The cross-cultural references of Moshiri’s artwork bridge the gap between Iran and the West in a way that resonates with both audiences.

“By showing images we all share—a cartoon we saw as children or a movie we saw as an adolescent—we create visual language that crosses borders,” says Shiva Balaghi, a cultural historian of the Middle East.

“I try not to be too inspired by other artists. Having said that, I think Andy Warhol and his Soup Can series have permanently rented a room up in my head.”

– Farhad Moshiri

Photo: Claire Dorn

Photo: Claire Dorn“That becomes a political statement when it comes from an Iranian artist whose work is being shown in the United States. Leaders of both countries tell us that our cultures are completely separate. It’s as if they are opposite extremes and it’s us versus them. Farhad’s art is saying that we have a lot of commonality in the way we see and experience the world. These cultures have a shared visual history we can all tap into, and that makes a deep political statement.”

“This exhibition is really going to open up Farhad’s work to a new audience,” says José Carlos Diaz, The Warhol’s chief curator and organizer of Go West, noting that much of the work will travel to the United States for the first time. While Moshiri has been exhibiting his paintings internationally since 1989, this moment marks a mid-career survey representing several key bodies of work made over decades.

“I think people will appreciate the aesthetics of the show. They’ll find there is something very beautiful about a lot of the paintings,” Diaz notes. “And they’ll walk away with a deeper understanding of a contemporary artist from another part of the world who is part of a global conversation. It’s significant that this is his first solo museum show, and it’s not in New York City, and it’s not in London or Paris but Pittsburgh—and at The Warhol.”

That excitement goes both ways. “It feels unreal,” says Moshiri, who splits his time between Tehran and Paris. “Actually, I’m quite beside myself. I couldn’t have predicted it in a million years.”

Inspiration in the everyday

During his teen years in the United States, Moshiri was drawn to the work of contemporary American artists, finding their work crisp and fresh compared to those in Europe. At boarding school, his art teacher introduced him to the work of Jackson Pollock. “I had such a blast imitating him, as so many others did,” recalls Moshiri. He also admired the work of John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Andy Warhol.

“I try not to be too inspired by other artists,” says Moshiri. Finding his own sources of inspiration, he notes, keeps his work from taking on the traits of others. “Having said that, I think Andy Warhol and his Soup Can series have permanently rented a room up in my head.”

At CalArts, Moshiri fulfilled his childhood ambition of studying film. But when he returned to Iran as a young artist, his creative instincts were thwarted by the Iranian regulations on film. He couldn’t make the kind of movies he wanted. So, he turned to other creative outlets. He began to collect everyday objects and transform them in a way that made a statement. He covered traditional furniture in gold leaf, merging classic European lines with the bling of contemporary Tehran, where new money was being displayed lavishly. “It was kitsch and garish and he was questioning taste levels,” says Diaz.

Moshiri also began scouring for “ordinary objects” to use in his artwork. He became fascinated with ancient jars and bowls from the Qajar dynasty of the Persian empire. At first, he collected the works, but then moved onto making monumental paintings of them. Layer upon layer of paint gives the jars a distressed look on the canvas.

One day, an unexpected finding—a bucket of crystals taken from dismantled chandeliers—inspired a new twist to the jar paintings. He saw the new accessory as a symbol of “the new money that was being flaunted across the city of Tehran, just like before the revolution,” Moshiri notes. “It spoke of the social paradox I witnessed.”

One such work, created in 2007, shows an otherwise-traditional Persian jar painted in hot pink, the word Faghat Eshgh (Only Love) spelled out in Swarovski crystals. “It’s this declaration of love,” Diaz says, “but then again, it’s also super kitsch and super glammed out.”

[media-credit name=”Farhad Moshiri, Faghat Eshgh (Only Love), 2007, Oil, tempera, crystals, and glue on canvas, Private collection, Switzerland” align=”alignnone” width=”900″]

Farhad Moshiri, Faghat Eshgh (Only Love), 2007, Oil, tempera, crystals, and glue on canvas, Private collection, Switzerland

Farhad Moshiri, Faghat Eshgh (Only Love), 2007, Oil, tempera, crystals, and glue on canvas, Private collection, Switzerland[/media-credit]

Moshiri is always experimenting with new ways of painting. When his wife stumbled across an old cake piping kit from the 1960s, he began applying paint on a canvas the way a pastry chef would decorate a cake. For him, it reflected his homeland’s post-revolution focus on consumerism and consumption. Luscious drips of paint evoke the lavish middle class Persian wedding cakes. “I would put acrylic paint in one end, squeeze it, and happiness would come out the other end,” Moshiri told Interview magazine in 2014.

The artist puts to use another kitchen utensil, the knife. The idea came in 2008 when he was working on an exhibition in Brussels at Galerie Rodolphe Janssen titled Home Sweet Home. Each work in the show represented a room in a house. “I had one work for the kitchen and suddenly the idea of sticking knives into the painting came to me,” says Moshiri. “I had already been using an icing-set syringe to create cake decoration with acrylic paint instead of frosting, so I was already using kitchen utensils instead of paint brushes. The progression was relatively smooth.”

While shopping for knives, Moshiri discovered antique treasures, handmade and signed by the maker, at the Tehran flea market. He also learned about traditional knife-making in Zanjan, an area north of Tehran. He began collecting these knives, setting aside half for his artwork and half for his personal collection.

The sculptures he creates with them, he says, work on the assumption that opposites attract—a “soft” word coupled with the hardness of metal knives. For an exhibition at the Galerie Perrotin, Paris, he stuck 600 knives into a wall to create the message Life is Beautiful. For The Warhol, he has a new message planned: Tranquility. He’ll provide Diaz with instructions on the exact placement for each knife.

“I love the easygoing approach to this type of art-making,” says Moshiri. “I find a word or phrase, go shopping for the knives, and stick them in the wall. No stress! If a knife breaks, I get another one—I love the fact that knives are replaceable. The work is in the gesture and the thought, and I find that very liberating.”

Diaz notes that sticking knives directly into the drywall shows the multi-faceted nature of Moshiri’s work. “What is so beautiful about this is that the knives function as subject and medium. The knives also are the only way to install the work. There’s no glue. There’s no string. The sharp blade is what holds them in place.”

Farhad Moshiri, Once Upon a Time, 2011, Acrylic embroidery, plastic pearls, crystals, glitter and glaze on canvas

Farhad Moshiri, Once Upon a Time, 2011, Acrylic embroidery, plastic pearls, crystals, glitter and glaze on canvas“What does art mean in our society? What do we consider to be a painting? How do we live with objects in our world? If Warhol was dealing with Middle America and class issues, Farhad is asking those questions on a more horizontal level, both cross-culturally and globally.”

– Shiva Balaghi, Cultural historian

Post-Pop examination

Moshiri’s intricate hand-beaded paintings are based on the beautiful embroidery found on the walls of Iranian households. He makes use of this traditional and well-known material yet resists the imagery normally associated with it. He hires local Iranian artists to do the beading work by hand based on his specifications, a process that can take months per painting. Though he often makes his own art by hand, he isn’t bound to the idea. “I see the art-making as a thinking process, followed by finding a way to create it,” whether by his own hand or any other means.

The artist says he lets sheer intuition guide his artistic choices, and he doesn’t overanalyze them. “I like to leave mystery in the work for myself and for the viewer. My gallerist in Brussels, Sebastien Janssen, used to ask me about my work by saying, ‘Where is the key? Where is the key?’”

“What key?” Moshiri would ask him.

The gallerist repeated the question until Moshiri realized what he meant—the story that would explain it.

“Oh, that key? I don’t want to give it to you.”

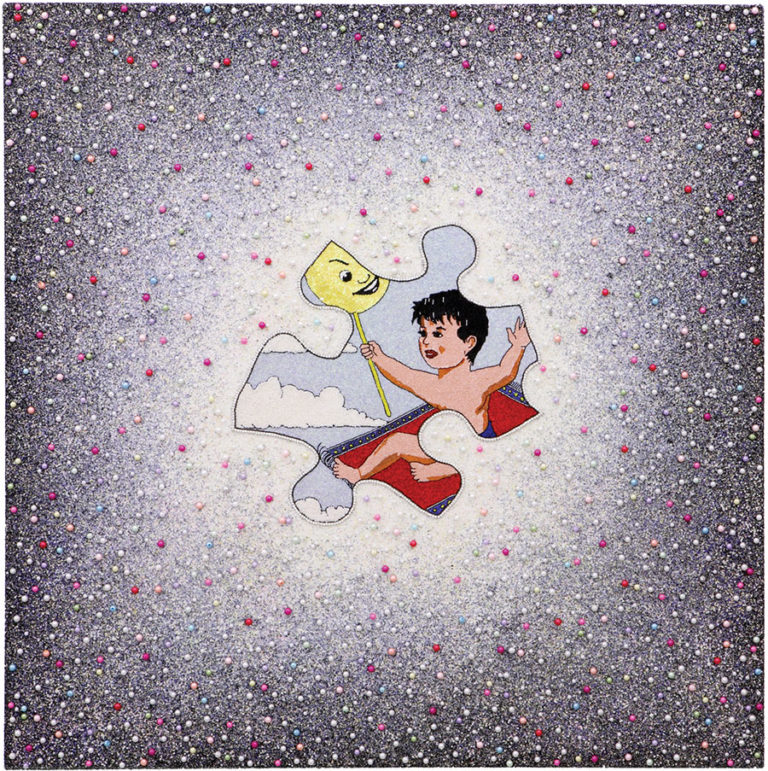

That ambiguity is part of his appeal, Diaz says. Consider the work Friends Forever (2009), which features mismatched puzzle pieces on a canvas of embroidery and paint. At first glance, the scenes of a child opening a bird cage and a young girl grabbing for an apple seem to depict innocence. But look again—is the child hurting the bird? Is that apple poisonous? A subtle ominous quality seeps into the work.

Drawing on his admiration for film, Moshiri’s paintings create short narratives with strange, vague instances. “These are moments where you don’t know what came before and what happened afterward,” Diaz explains.

Moshiri says of his art that features puzzle pieces, “Finishing a puzzle was always a very tedious job for me. I never had the patience.”

[media-credit name=”Farhad Moshiri, Self portrait on flying carpet, 2009, Embroidery and acrylic on canvas, Courtesy Galerie Perrotin, Photo by Guillaume Ziccarelli” align=”alignnone” width=”768″]

Farhad Moshiri, Self portrait on flying carpet, 2009, Embroidery and acrylic on canvas, Courtesy Galerie Perrotin, Photo by Guillaume Ziccarelli

Farhad Moshiri, Self portrait on flying carpet, 2009, Embroidery and acrylic on canvas, Courtesy Galerie Perrotin, Photo by Guillaume Ziccarelli[/media-credit]

In Self portrait on Flying Carpet (2009), he places a lone puzzle piece featuring a boy on a flying carpet in the center of a large, beaded canvas that shimmers. Moshiri makes many self-portraits, but they don’t resemble him physically. He shuns the celebrity art world, preferring to call as little attention to himself as possible. As he puts it, “I don’t self-advertise to family and friends for fear I might come across as a showoff. I’m timid and uncomfortable when I get attention.”

He received more attention than he may have wanted in 2008 when he became the first artist from the Middle East to sell a painting—which featured the Farsi word for “love” embroidered in Swarovski crystals and gold sequins—for more than $1 million at auction. Diaz says it gave him prominence globally, but he also experienced backlash by some who labeled him an auction-house darling. Moshiri is sometimes called the Andy Warhol of the Middle East—a comparison Diaz calls simplistic.

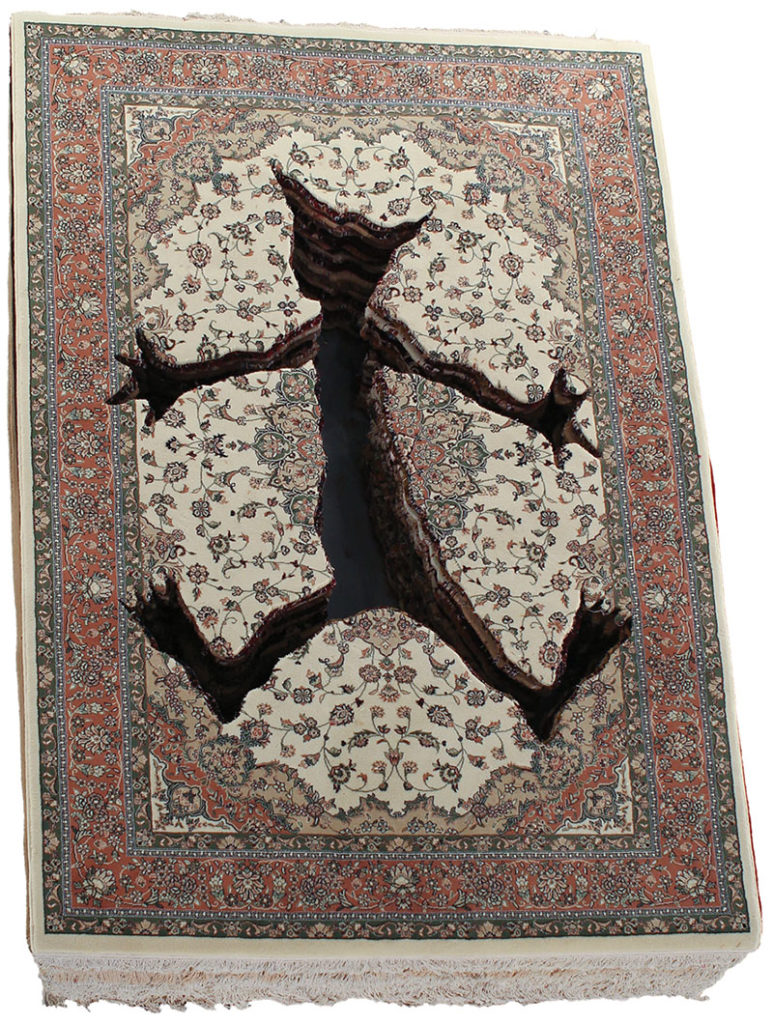

[media-credit name=”Farhad Moshiri, Crash, 2011, 43 stacked machine-made carpets, Courtesy of The Farjam Foundation, UAE” align=”alignnone” width=”773″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

“He is an heir to Warhol, and he does borrow and find inspiration from Pop,” says Diaz, acknowledging their shared affection for everything from appropriation to collecting and readymades. “But he is far more complicated in that he borrows styles and aesthetics from different artistic movements and differentgeographical parts of the world—the United States, of course, as well as contemporary Iranian culture and Persian traditions.”

Balaghi says Moshiri’s art is a post-Pop examination of some of the same questions that Warhol posed decades earlier. “What does art mean in our society? What do we consider to be a painting? How do we live with objects in our world?

“In that sense, The Warhol is really the perfect place to show Farhad,” Balaghi notes. “His work is addressing the same questions in a 21st-century context. If Warhol was dealing with Middle America and class issues, Farhad is asking those questions on a more horizontal level, both cross-culturally and globally.”

Farhad Moshiri: Go West is generously supported by Piaget, The Fine Foundation, and the Soudavar Memorial Foundation, with additional support from Fatima and Essi Maleki, Ziba Franks, Navid Mirtorabi, Elie Khouri, Maryam and Edward Eisler, and special thanks to Galerie Perrotin, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, and the Third Line, Dubai.