|

||||||||||||

|

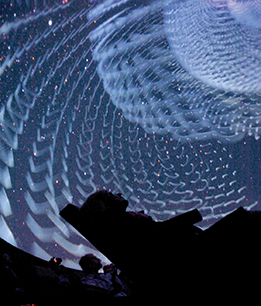

“My world changed that day. My universe grew enormously, from a small chunk of a single planet, to a whole cosmos of innumerable stars, worlds, and galaxies.” - Brendan Mullan, Director of Buhl PlanetariumAbove Photo: Rebecca Hale/National Geographic Society |

Thinking Like a Scientist

Celebrating 75 years as an inspiration to countless starry-eyed kids, Buhl Planetarium remains one of the Science Center’s best bets for lighting that early spark of scientific wonder and curiosity.Imagine a place that seems so near yet is truly unbounded. A place that seems constant yet is ever-changing. A place so familiar yet so wondrous that it inspires artists and scientists alike. That place is the night sky. In addition to being on display every evening in your backyard, it’s also playing at a theater near you—Carnegie Science Center’s Buhl Planetarium & Observatory. For much of the beloved attraction’s 75-year history, shows like Stars Over Pittsburgh, The Little Star that Could, and The Sky Above Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood have set the stage for the region’s big dreamers—not to mention its aspiring astronomers—by expanding their horizons. “When people come here,” says Dan Malerbo, planetarium coordinator, “they want to see the stars. They’re curious, and it’s that curiosity that gets them hooked on the universe. The next thing you know, they’re learning about string theory.” Maybe. But whether or not physics is in your future, studying the stars is a natural gateway to science and a better understanding of our own world.

Just ask Brendan Mullan. Like many kids growing up in the ’90s, he watched a lot of X-Files. This got him thinking about space, which made his trip to the local planetarium even more mind-blowing. A native of Buffalo, New York, Mullan vividly recalls sitting in a dentist-like chair watching in awe—and a bit of panic—as a mechanical projector that looked like a giant mutant insect rose from the floor and began to glow. “This is really cool!” Mullan remembers thinking at just 8 years old. No doubt, many Pittsburghers have similar memories of the now-retired Zeiss Model II, as all 12 feet and 6,000 pounds of it made a similar grand entrance at the original Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science. “My world changed that day,” Mullan affirms. “My universe grew enormously, from a small chunk of a single planet, to a whole cosmos of innumerable stars, worlds, and galaxies.” Fast forward to July 2014 and you’ll find the 29-year-old on the job as the new director of today’s just-as-wondrous, high-tech Buhl Planetarium. Armed with a doctorate in astronomy and astrophysics from the Pennsylvania State University, and sporting Converse sneakers (no socks, of course) and jeans, he’s ready to battle the stereotype that scientists are a bunch of pipe-smoking, white-coat-wearing elitist nerds, and that science is not relevant to our everyday lives. SCIENCE FOR LIFEScientists have played an undeniable role in Mullan’s life. Since his mom works in a biology lab and his dad is a chemical engineer, you could say science is the family business. “I didn’t necessarily know what scientists did,” he says, “but I knew who they were; they were sitting across from me at the dinner table.” That sense of purpose and possibility is something he’s trying to pass on to all kids. Mullan is making it his personal mission to reach out to young people and encourage them to boldly go where no one has had to go before. And that’s not hyperbole; as far as he’s concerned, our collective future is not necessarily bright. “Our challenges are different today,” says Mullan. “There’s climate change, resource depletion, overpopulation, and our outdated, declining infrastructure. To address these issues, we need people who are able to ask the right questions and think through problems like scientists.” So, how do scientists think? The short answer, says Mullan, is ASAP: Ask why and figure out how. Solve problems. Argue your case with evidence and conviction. Provide value to others. From Mullan’s perspective, there has to be more to science than just the science. That’s why he’s urging the next generation to see the big, intergalactic picture. According to Ron Baillie, the Science Center’s Henry Buhl, Jr., Co-director, that’s exactly the outlook that will help the planetarium navigate the 21st century and beyond. “Mullan is a young guy, he’s extremely accomplished, and very energetic,” says Baillie. “But most importantly, he’s a world-class communicator.” Those communications skills, not to mention his intellect, earned Mullan top honors in the 2012 NASA FameLab competition. FameLab was founded in 2005 as a means of encouraging budding scientists to share their ideas directly with the public in presentations lasting no longer than three minutes. Since then it’s gone global, with more than 3,800 researchers participating in 20 countries.

This user-friendly, plain-speaking approach to science took another leap forward in 2013 when he was named to that year’s National Geographic team of Emerging Explorers. This diverse group included an anthropologist, a computational geneticist, an innovative entrepreneur, and a data artist, and was hailed as “the next generation of innovative scientists and visionaries pushing boundaries of discovery, adventure, and global problem-solving.” Mullan then set off on a national tour of schools, talking to students about why inquiry-based thinking matters and advising teachers on why the way they communicate about science can make all the difference. While earning these accolades and awards, Mullan was also working toward his doctorate. In whatever time he could spare, he developed a Penn State undergrad course that encouraged students to think about humanity’s long-term sustainability and survival; he started an astrobiology summer camp where middle schoolers could search for life on distant worlds; and he encouraged his community to turn its gaze skyward. “It all felt challenging to me,” Mullan says. “What’s the point of taking it easy?” Now that he’s landed in Pittsburgh, the question is, what’s the next challenge going to look like? But first things first. Mullan is smart enough to know that “what’s new and what’s effective are not necessarily the same (think 3D televisions).” He acknowledges how important the history and nostalgia associated with the Buhl Planetarium are to southwestern Pennsylvania. DEMOCRATIZING SCIENCELong before Mullan was born, local businessman Henry Buhl, Jr., wanted to find a way to give back to the city that made him a very wealthy man. So he established the Buhl Foundation. With nearly $1.1 million of funding from the foundation, the Buhl Planetarium and Institute of Popular Science opened in 1939, becoming the fifth major planetarium in the United States, along with those in Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia.

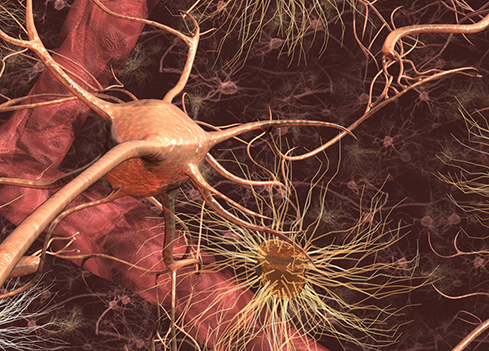

For decades, the Buhl Planetarium was a North Side landmark and favorite destination for school field trips. Then in 1982, it morphed into the Buhl Science Center, and five years later merged with Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. In October 1991, a reimagined planetarium and observatory debuted as part of the newly constructed Carnegie Science Center near the old Three Rivers Stadium. Throughout its 75 years, the planetarium has managed to more than keep pace with technology. Once the Zeiss (which, by the way, can still be seen in all its glory on the first floor of the Science Center) was retired, a series of newer, smarter, computerized projection systems followed. Today, a stateof- the-art, full-dome, interactive, digital system fills the 150-seat, 50-foot dome theater with amazing images and animation from outer space (Back to the Moon for Good and Cosmic Collisions) as well as glimpses into the human body (Journey into the Living Cell and Tissue Engineering for Life).

This diversity of content is one of the planetarium’s most far-reaching accomplishments. Thanks to collaborations with a variety of organizations including NASA, the National Institutes of Health, and GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare, the Science Center is a significant producer of programming for the world’s 3,000-plus planetariums. But for Malerbo—who, like Ron Baillie, worked at the original Buhl—today’s planetarium is more than just the sum of its parts. “It’s our entire educational philosophy that defines us,” he asserts. “We keep growing, learning, and sharing with the public. There’s no stagnation; we’re very progressive.” Baillie agrees. “Change is in our DNA.” But he notes that the Science Center not only reflects a changing world but also strives to influence it.

“For us, it’s absolutely essential that we contribute to a scientifically literate society. The more the public understands, the more it can think critically, ask relevant and meaningful questions, and make better decisions.”

- Ron Baillie, Carnegie Science Center Co-DirectorAlready a proven leader in informal science education, the Science Center is now leading the regional charge in critical STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education with a focus on uniting vast community resources. In 2011, the Science Center established its Chevron Center for STEM Learning and Career Development, an important next step in rallying the region behind a cause that has always been important to the Science Center but is now becoming critical to the technology industry at large: creating a more science-literate and science-driven community of children and adults. The need has never been greater, Baillie says. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, eight of the 10 fastest-growing occupations in America are science-, math-, or technology-related. As of last year, national jobs in science and engineering had increased by 2.2 million. But far too few students in the United States are prepared to meet these mounting demands on the country’s labor force. What’s more, many teachers are ill-equipped to train them. In Pittsburgh’s technology sectors alone, at least 2,000 STEM positions remain unfilled, jeopardizing the region’s economic future. “For us, it’s absolutely essential that we contribute to a scientifically literate society,” says Baillie. “The more the public understands, the more it can think critically, ask relevant and meaningful questions, and make better decisions.” As Mullan settles into life at the Science Center, he’s faced with some decision-making of his own. He’s still wondering what do with all the stuff in his office. That nondescript box sitting in the corner? There’s an honest-to-goodness 60-pound meteorite chunk in it. Pretty awesome. And that piece of carpet shoved under the desk? Neil Armstrong—yes, the guy who walked on the moon—actually stood on it during a visit to the Science Center. Pretty inspiring stuff. Then there’s the note he received last summer from one of his middle school campers, which he knows he won’t be parting with anytime soon. “Dear Dr. Brendan,” the hand-printed card reads. “Thank you for hosting such a wonderful camp this week! I believe that this camp was my favorite of all [Penn State camps] I have been to so far. I learned lots of different information about astronomy that I didn’t know before. ☺ Thanks again, Maddie I.” With that same spark of enthusiasm and passion he felt at his first glimpse of that giant telescope at age 8, Mullan grips the card and proclaims, “This is really cool!”

|

|||||||||||

Storyteller · Shock and Awe · Look Again · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Jo Ellen Parker · Artistic License: Out of the Vault · About Town: Let's Talk about Race · Science & Nature: The Body on Stage · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |