Fall 2014

Fall 2014|

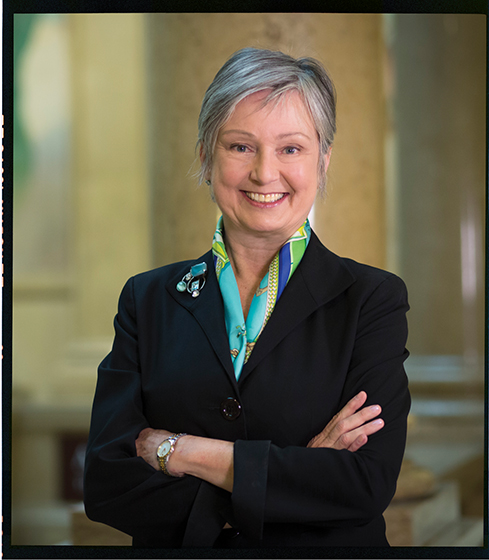

Jo Ellen Parker

Among Jo Ellen Parker’s most prized possessions is The Gift, a 4-foot-high sculpture of a Buddhist monk holding an empty space between outstretched hands. “The space he offers—the gift he carries—is pure potential,” explains Parker, the 10th president of Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, who considers it her primary role as leader to seek out those sweet spots of potential where collaboration is both natural and game-changing. “Holding a space,” as she describes it, “where bright and engaged people come together and find where their passions and priorities overlap.” Early on, the savvy educatorturned- CEO followed her passion for literature all the way to a doctorate in English. But after a number of years as a professor and college administrator, her focus shifted to nonprofit entrepreneurship. This led her to assume CEO roles at the Great Lakes Colleges Association, a consortium of 13 liberal-arts colleges, and then at the National Institute for Technology in Liberal Education—little more than a series of grant-funded projects until Parker turned it into a sustainable nonprofit serving nearly 150 colleges in the United States and abroad. For the past five years, she’s served as the much-admired, enterprising president of Sweet Briar College in Virginia. All three leadership stints reflected her impassioned determination that nonprofits—including museums—must earn their place in a tenuous economic future by being more mission-driven, collaborative, and entrepreneurial. “These are tough times for nonprofits,” she notes. “I’ve believed for years that collaborations between nonprofits with similar missions can keep those organizations strong and extend their reach.” Where do you see the potential for collaboration here?One of the inspiring aspects of the museum mission is that more Americans encounter the liberal arts and sciences in museums than, for example, colleges. There are obviously practical opportunities in such areas as centralized services and resource sharing. But there are intellectual opportunities as well; issues, moments in history can be presented from scientific, historical, and artistic points of view through collaboration, creating a multi-dimensional set of programs for patrons. What’s your secret for getting things done?There’s no secret! Relationships matter. It’s all about bringing people together, defining shared goals, and helping people help each other. Do any past experiences in museums stand out to you?As this opportunity presented itself, I realized how easily I could tell my life story in museums. I think first about the Nelson-Atkins in Kansas City; my mother was a docent, and as a child I spent untold hours there. I could still describe the Japanese hall in loving detail! I think of taking my son to The Franklin Institute and the Philadelphia Museum of Art when he was little. Thank goodness for armory, the best way to get a little boy into an art museum—knights! swords!—and for the educators at The Franklin who got him excited about science. More recently, in my husband’s hometown of Detroit, the challenges facing the Detroit Institute of Arts has only underlined for me the importance of vital museums to a sense of civic pride and identity. What are you most proud of from your time at Sweet Briar?Creating a more socially inclusive college was a central commitment of my work there. When I arrived, the percentage of students who identified themselves as non-white was in the single digits. This year, it’s more than a quarter. Socioeconomically, too—more than a third of today’s Sweet Briar students are eligible for Pell support or are first-generation college attenders. The ability to ensure that all students have access to the finest education—as a society we must treasure that and fight for it. You moonlighted as a “Nia” instructor at Sweet Briar. How did that come about?When I lived in Michigan I studied Nia [a combination of martial arts, dance, and yoga] and loved it. But when I moved to Virginia there were no Nia instructors within 50 miles, so I trained as an instructor myself. I’ve done three belts so far! On campus, I’d offer free classes as an expression of my commitment to employee wellness. It was a delight to get to know faculty, staff, spouses, and students of all ages and fitness levels in those classes. As it happens, there are no Nia teachers in Pittsburgh, so I have yet to figure out how I will continue my Nia practice here. What inspired you to take this position?My flippant answer is: Who wouldn’t want to do this job? Each of the four museums is a gem; it is an honor and a privilege to contribute to their work. Pittsburgh drew me and my husband to this position as well. The chance to be part of a community that so obviously cherishes its cultural organizations was irresistible. My focus, of course, is Carnegie Museums. But as I’ve gotten to know the city, I see so many other cultural organizations, universities, and performance groups that make this a thriving community. I look forward, personally, to becoming engaged across the city’s cultural landscape.

|

Storyteller · Shock and Awe · Look Again · Thinking Like a Scientist · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Artistic License: Out of the Vault · About Town: Let's Talk about Race · Science & Nature: The Body on Stage · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |