|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Sebastian Errazuriz and his wall of sketches inside his Brooklyn studio. Photo: Jason Falchook |

Look Again

Artist and designer Sebastian Errazuriz provokes viewers to rethink the everyday.Fifteen years ago, Sebastian Errazuriz was walking through his native Santiago, Chile, scoping sites for a public art project, when he came upon a rundown taxidermy museum that was going out of business. The owner had been clearing the space and piling the unwanted animals, mostly birds and reptiles, along the sidewalk for the dumpster. Among them was a large, white goose. The 21-year-old design student knelt down for a closer look. The bird smelled. Its neck was broken, its head flopped to one side, and its chest puffed, rigid and unmoving. Errazuriz thought it was “disgusting, awkward, and morbid.” Yet somehow, he says, it seemed funny? Weirdly elegant, even. Darkly cute? Errazuriz had been struggling to find confidence in his ideas, and here he found a concept he loved. He plucked the goose from the pile and told the museum owner he’d be back with an idea and a blueprint.

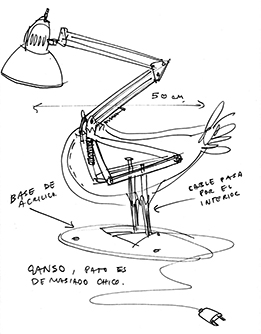

The sketch Errazuriz brought to the taxidermy museum replaced the goose’s head with a task lamp, reinforced its interior with wire scaffolding, and ran a hollow rod through one leg to allow for an electrical cord. The owner was skeptical but complied. “Sure kid,” he said, “I’ll have it for you in three weeks.” For its title, says the artist, Duck Lamp just had a better ring than Goose Lamp. Rachel Delphia, the Museum of Art’s Alan G. and Jane A. Lehman Curator of Decorative Arts and Design, first saw Errazuriz’s work in 2011. “I love Duck Lamp,” she says, “because I think he made it before he fully understood his process.” Today Errazuriz sketches for several hours a day with black pen on paper. He works from an undeniably comfortable Brooklyn studio that he transformed from a hollow shell within an old industrial building. With white walls, large windows, and lofty ceilings, the space is now home to a gallery, woodshop, and an office for a staff that numbers between four and 10, depending on the day. Each day at 5 p.m. the computers are shut down, the tools are shelved, and Errazuriz is left alone to set his thoughts to paper. Sketching is an exercise he learned as a kid in London, where his dad completed a doctorate in arts education and assigned him daily, rigorous creative assignments. “I really believe most of the good ideas you get come from your unconscious side, not your rational side.”

- Sebastian Errazuriz“I really believe most of the good ideas you get come from your unconscious side, not your rational side,” says Errazuriz, now 37. “You’re like a medium. You’re receiving things, taking it down and trying to make sense of what you’re seeing.” As he explained once to Delphia, sketching is “like turning the tap on and paying attention to what comes out.” LIFE AND DEATHBoth his family and his boyhood schools were strictly Catholic. He prayed at the start of class, confessed his sins every week at school, and went to mass with his parents on Sundays. Shortly before Errazuriz was born, his uncle Panchito died of diabetes in his twenties. His uncle, who had just completed architecture school, had refused to live under the strict diet and health regimen his doctors prescribed. “To suddenly have your brother, or your son, decide that he’s not going to look after himself is almost like a death sentence for the whole family,” says Errazuriz.

“Being very young, there was always this awareness of mortality,” says Errazuriz. “I had a really happy childhood, but I just knew that life was short. I knew that you could die. That for me was very liberating, because it helped put things into perspective.” Little by little, Errazuriz grew unsure about the rules of Catholicism. It’s stupid we can’t eat meat on Fridays, he thought. He became skeptical about the power sought by members of the church. A priest has no more sainthood than I do, he decided. By 13, he was an atheist and considered suicide a tool of empowerment. Without that option, he reasoned, we are not choosing to live. So much of Errazuriz’s work today addresses the human condition from this sense of morbid empowerment. There is El Santo, a chair with a halo that transforms any sitter into a saint, and Emergency Crucifix, an inflatable cross for an airplane crash over water. THE PROBLEM SOLVERTo begin working, Errazuriz always sketches with a problem in mind. Sometimes, as in the case of commissions—which account for about 10 percent of his output—the problem is tangibly defined. He needs to create something of a certain size, with a specific function, on a set budget while maintaining his standards for aesthetics and meaning. Reflection Desk, for example, is a small writing table that includes a small adjustable mirror so that the sitter will occasionally catch his own eye while working and be reminded to stay present; that he is alive.

Other times, as with his public art, Errazuriz begins with a social or political issue and creates work that seeks to challenge a problematic status quo. For The Tree Memorial of a Concentration Camp in 2006, he planted a magnolia tree in the Chilean National Stadium where former dictator Augusto Pinochet murdered thousands in 1973. The stadium opened as a park, and after a week the national soccer team played a match while the tree still stood in centerfield. A constant problem solver, Errazuriz often capitalizes on better-paid commissions and gallery sales to underwrite his social experiments, a video compilation of which will be included in Look Again. One day while sketching, seemingly unprompted, he drew a small man standing with a piano hung above his head by a rope. The caption read, “The piano!” As is typical for him, Errazuriz was spending the afternoon thinking about death and randomness, the absurd abruptness with which life can end.

“A hanging piano is such a stupid cliché,” Errazuriz admits, “but it occurred to me that as stupid as it was, if I actually realize it, the idea has this extra depth and weight.” So Errazuriz hung a real piano by a rope in his studio and worked that way for five years. The piano became so much a part of his background that occasionally he’d forget about it, walk underneath while absorbed in a phone call, and then dart away with a muttered expletive realizing the risk he was in. “It was this really beautiful challenge of: Hey, you like to talk about being aware? Put your money where your mouth is.” A replica of the piano will make its public debut in the museum’s Hall of Architecture. EYES WIDE OPENErrazuriz believes an artist, much like a comedian, is capable of delivering a truth that resonates. He incorporates humor—a “vital lubricant” in his words—into his own work as a way to address difficult subjects people might otherwise reject.

The exhibition’s title piece, made in 2011, is a simple white door with two peepholes side by side. It’s Errazuriz’s philosophy embodied. “We’ve been closing one eye for decades, for centuries, and it doesn’t make sense,” he says. “Why not invite people to open the other eye and see more?” Counterbalancing his fascination with mortality and rejection of the afterlife is his insistence that this life has much to discover, if you are fully awake to it. In Look Again, a series of fantastical cabinets prompts this thought exercise. As a design student in Chile, Errazuriz continued adding tools to his creative arsenal. His grandfather, who worked for a nearby shipping company, owned a small woodshop and built ship models and carved crucifixes during his free time. There, Errazuriz learned to work with wood. But he does not consider himself a master woodworker. In fact, he uses the term “we” when discussing the fabrication process and praises the skills of his team.

Inspired by the playful work of 18th-century cabinetmaker David Roentgen—famous for creating ingenious secret compartments and hidden levers—Errazuriz understands how different materials and unexpected functions can work to communicate his ideas. “What’s really powerful about his work is the cumulative action of looking again at so many different things. It gets at an entire way of thinking.”

- Rachel Delphia, The Museum of Art's Curator of Decorative Arts and DesignKaleidoscope, made of walnut and lined internally with mirrored glass, distorts whatever objects are placed inside, viewable through a peephole. Magistral, covered in 80,000 bamboo skewers, resembles an armored safe but glides open to reveal a series of staggered compartments. Explosion, crafted this year, is his most ambitious cabinet and was recently acquired by Carnegie Museum of Art. At approximately five feet wide, it’s composed of thin strips of maple that telescope outward on a series of runners until each one overlaps by only five inches. When the piece is expanded fully on sides, top, and bottom, it stretches for 22 feet and ceases to be a cabinet, says Delphia, “because there is no longer a space to contain.” The metaphor was easy, but the expression, the cabinet, took a year to construct. What unites Errazuriz’s work is not necessarily aesthetic. Look Again includes high-heeled shoes made of resin through 3-D printing; a fire screen carved to resemble the Chilean palace La Moneda, which burned during the coup d’état in 1973; and chairs made for protestors in the Occupy movement, eight of which the museum also acquired. What links the work is the idea behind it. It’s a message resulting from a life experience that is entirely his own. Look Again is a prescription for others to live life as he does—with eyes open—should they choose to.

|

||||||||||||||||

Storyteller · Shock and Awe · Thinking Like a Scientist · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Jo Ellen Parker · Artistic License: Out of the Vault · About Town: Let's Talk about Race · Science & Nature: The Body on Stage · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |