|

||||||||||

|

Shock and Awe

Why one of the world's most abundant birds went from billions to extinction in less than 50 years, and how the lessons it taught us—now a century old—are more timely than ever.In January of 1810, Alexander Wilson, a Scottish-American naturalist who would become the father of American ornithology, set out on a six-month journey to collect and illustrate the birds of his adopted country. The school teacher traveled alone from his home in Philadelphia west to Pittsburgh. As he continued along the Ohio River in an open rowboat, he would occasionally rest his oars, gazing up at what he described as endless streams of migrating pigeons pouring out of Kentucky toward Indiana, “marking a space on the face of the heavens resembling the windings of a vast and majestic river.”

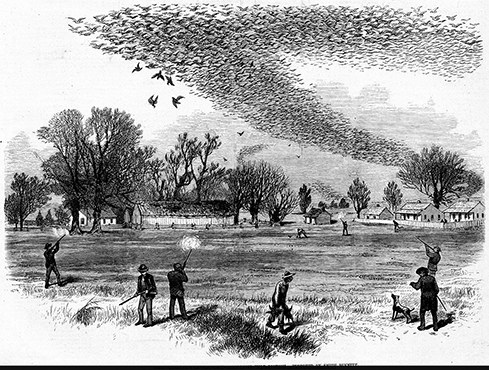

One day, he paddled ashore to buy milk from a farmer. While he was inside a cabin talking, he was nearly swept off his feet with fear: “I was suddenly struck with astonishment at a loud rushing roar, succeeded by instant darkness,” wrote Wilson, “which, on first moment, I took for a tornado, about to overwhelm the house and everything around it in destruction.” To which the farmer calmly replied, “It is only the pigeons.” Wilson rushed outside to find a massive flock swooping low between the cabin and a high bank across the river. Evoking equal amazement and alarm were passenger pigeons, at the time the most abundant bird in North America, and possibly the world. When Europeans arrived on the continent they seemed inexhaustible, numbering from three to five billion and accounting for 25 to 40 percent of all bird life. They dominated the United States and Canada from the Atlantic Coast to the Missouri River, migrating seasonally by the millions and, in the process, “rendering normal conversations inaudible” by one account, blotting out the sun for hours, and the furious downward clap of their wings chilling the air below. In 1813, famed naturalist John James Audubon recorded a flight along the Ohio River that eclipsed the sun for three days. It was a phenomenon—and a guaranteed meal—familiar to farmers and city-dwellers alike. “Unlike the bison, you didn’t have to travel anywhere remote to see them,” says Joel Greenberg, the Chicago-area naturalist who spent years researching the bird for his recent book, A Feathered River Across the Sky: The Passenger Pigeon’s Flight to Extinction. “Not necessarily every year, but for days in the spring and days in the fall, clouds of birds would fill the skies. People shot at them from their porches in Manhattan.” The passenger pigeon’s largest nesting site was recorded as late as 1871 and included an estimated 136 million birds covering 850 square miles of central Wisconsin, roughly the size of 15 Pittsburghs. “There were birds in nearly every tree,” says Stanley Temple, an avian ecologist and wildlife biologist from Wisconsin who has spent his career studying and saving threatened animals and their habitats. A single gun dealer in the tiny railroad crossing town of nearby Sparta reported selling more than a half-million rounds of ammunition over the two-month nesting season, contributing to the demise of an estimated 1.2 million birds at this single site. “It’s believed that 100,000 people participated in the slaughter,” Temple says. “It must have been absolute chaos.” Just 28 years later, the last confirmed wild passenger pigeon was shot in Ohio, and a short 15 years later, on September 1, 1914, the last one in the world, a captive bird named Martha (after President Washington’s wife) died at the Cincinnati Zoo. This September marks the 100-year anniversary of the bird’s extinction; its journey from billions to none took fewer than 50 years. That we know the exact date—and nearly the exact time the species was wiped from the earth (between noon and 4 p.m.)—makes the at once shocking and awe-inspiring story of the passenger pigeon that much more captivating. A lesson for the agesPerched inside a large bell jar on the first floor of Carnegie Museum of Natural History are four red-eyed passenger pigeons from the museum’s collection, paired alongside a couple of smaller and still plentiful mourning doves—which, until recently, was believed to be the passenger pigeon’s closest relative. (Thanks to DNA testing, we now know the closest relative is actually the less common band-tailed pigeon). The tan (female) and mostly slate-blue (male) birds, which strut a rust-colored breast and a patch of iridescent neck feathers, are the stars of the museum’s contributions to an international effort dubbed “Project Passenger Pigeon.” Organized by Greenberg and Temple, among others, and joined by museums, nature groups, educational institutions, and independent artists, the goal is to drive home the “teachable moment” these animals represent in a storyline that is as much about people as it is about birds. “It’s perhaps the best cautionary tale to the proposition that no matter how common or plentiful something is—it could be water or fuel or something that is alive—if we’re not good stewards, we can absolutely lose it,” says Greenberg. While it’s the most iconic example of human-caused extinction since the dodo bird (also a member of the pigeon family), the fascinating life and times of the passenger pigeon is largely unknown, concedes Greenberg, a fact he and others traveling the country spreading the passenger-pigeon gospel are working hard to change. Look for one of their marquee projects, the documentary Billions to None, on PBS and WQED this September. Fittingly, “passenger pigeon”—not to be confused with its distant cousin, the messagebearing or homing pigeon, which originated in Europe and is domesticated—is a corruption of early French settlers’ reference to the birds as pigeon de passage, which, as with the bird’s scientific name, Ectopistes migratorius, translates roughly as “wandering migrator.” Lured by beechnuts, acorns, and berries, the birds tore into eastern temperate forests like those of Pennsylvania, the weight of their collective bodies and nests bearing down like a biological hurricane, crippling trees. But the sometimes feet-thick nitrogen-rich droppings they left in their wake also promoted new growth. So, like a forest fire, the birds were both destructive and regenerative.

They were also easy targets. Tasty, convenient, and flying in flocks so thick that hunting required so little skill that even waving a pole or tossing a potato could make low-flying pigeons drop from the sky. After the Civil War, two technological advances—the telegraph and the railroad—made it much easier to communicate about the birds’ locations and reach them, fueling an already rapidly growing commercial pigeon industry that often employed whole families and towns. The birds were sold cheaply at about 31 cents per dozen. “The industry that paid people to kill these birds said, ‘If you restrict the killing, people will lose their jobs,” notes Greenberg, “Sound familiar?” When their numbers started to nose dive, people just couldn’t seem to believe it, making outrageous claims about their whereabouts. On this topic, Jonathan Rosen of The New York Times wrote, “The flocks were like phantom limbs that the country kept on feeling. Or perhaps the birds’ disappearance, and the human role in it, was simply too much to bear.” Memorializing MarthaTemple notes that there were dozens of species of birds and mammals on the brink of extinction around the same time the passenger pigeon met its fate—many of which, like the wild pigeon, were being commercially overkilled. Bison, wood ducks, wild turkeys, and beavers are prime examples. “But they made tremendous comebacks as a result of the 20th-century conservation movement that in no small way was catalyzed by the shock of the passenger pigeon’s extinction,” he says. In 1900, more than a decade before Martha took her last breath, Republican Congressman John F. Lacey of Iowa introduced the nation’s first wildlife-protection law, which banned the interstate shipping of unlawfully-killed game. “The industry that paid people to kill these birds said, ‘If you restrict the killing, people will lose their jobs. Sound familiar?”

- Joel Greenberg, naturalist“The wild pigeon, formerly in flocks of millions, has entirely disappeared from the face of the earth,” Lacey said on the House floor. “We have given an awful exhibition of slaughter and destruction, which may serve as a warning to all mankind. Let us now give an example of wise conservation of what remains of the gifts of nature.” That year, Congress passed the Lacey Act, followed by the tougher Weeks-McLean Act in 1913 and, five years later, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which protected not just birds but also their eggs, nests, and feathers.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, today 13 percent of birds are threatened, 25 percent of mammals, and 41 percent of amphibians. Why museums matterThis is why trusted repositories of natural-history collections such as Carnegie Museum of Natural History do what they do, says John Rawlins, head of the museum’s section of invertebrate zoology. “When emergencies happen in the environment, when an invasive species strikes, when there is a need to understand why a species is either reproducing too much or going extinct, it basically comes down to the need for information and context, and often that need is relatively rapid,” Rawlins notes. Museum collections and the research of museum scientists— which are all about tracing the origins and relationships of varying species—are often crucial in fulfilling this need. Case in point: Amphibians are in crisis. Frogs, toads, and salamanders are disappearing in record numbers because of habitat loss, water and air pollution, climate change, and disease, among other factors. Because of their sensitivity to environmental changes—unlike birds or mammals, for instance, their ability to adapt or simply relocate is limited—vanishing amphibians could be viewed as the canary in the global coal mine, signaling subtle yet radical ecosystem changes that could ultimately impact many other species, even humans. “A lot of my colleagues who work in Panama, in Ecuador, have seen their common frogs go extinct—the typical frog that you take for granted that it will be in the pond in spring,” says Jose Padial, the museum’s William and Ingrid Rea Assistant Curator of Amphibians and Repiles. “And they are gone forever. We are really transforming our environment.”

Frog populations, he says, continue to drastically decline the world over due to the spread of a killer fungus that belongs to a group known as chytrids (pronounced kit-rids). Scientists are still trying to understand what makes it tick, but one thing is for certain: humans are helping it spread through the trade and import of the animals, says Padial. Like her colleagues around the world, Patricia Burrowes Gómez, a researcher at the University of Puerto Rico, is trying to determine when the fungus arrived in her home island and what species it infected first. She’s also interested in knowing if there was a single wave of infection or several waves. To find out, she’s digging through museum collections, says Padial, including those at the Museum of Natural History, testing specimens collected over decades to see if they carried the disease but survived. In other words, she’s building an historical reconstruction of the pandemic wave moving through the island—something that is only possible through the use of museum specimens. “It’s a very dramatic thing,” Padial says. “It means that dozens of species are already gone in less than 20 years. We have some in the collections; the only way to see them now is in pictures or in jars.” Through its numerous collections, the museum is constantly contributing to triage science. The mammals section, for instance, has specimens of the endangered Florida panther and the rapidly declining little brown bat (once the most common bat species in the northeastern United States), both of which have been studied by outside researchers in an effort to solve the riddle of what’s contributing to their demise. “There are 100-year-old specimens in our collections, and those that represent species that are undergoing such radical changes today that they will be the next treasured remains preserved in a museum collection,” says Sue McLaren, collection manager for mammals. Past meets presentWould the existence of Powdermill Nature Reserve’s world-renowned bird banding program, now in its 53rd year, have made a difference to the passenger pigeon? Only if people were listening. Bird banding data has allowed scientists to conduct long-term nature studies.These studies are a gold mind of valuable data because they can reveal trends in population demography, biodiversity, and ecosystem stability—information critical to decision-making about current and future conservation issues, says Luke DeGroote, an avian ecologist and the bird banding program coordinator at Powdermill. “A bird population in distress indicates larger problems with the environment,” he says. “Our banding program serves as an early warning to when migrations happen earlier, populations shift north, and species begin to decline. Our long-term monitoring efforts help look at both the causes and the solutions.” As the environmental research center of the Museum of Natural History, Powdermill is also at the forefront of developing new techniques that are redefining how we learn about birds and their behavior. They record birds captured during banding to build a library of nocturnal flight calls that are then used to assess nighttime migrations, and help direct the placement of wind turbines to areas that birds do not use as flyways. And because more than 100 million birds are killed annually in the United States simply from colliding with windows, they’re testing many species of birds to measure how well they see various experimental glass formulas, helping to develop windows that are both unobtrusive to humans and visible to birds. “I’ve spent my whole career working on endangered species,” says Temple. “People ask how I can remain optimistic. My standard response is I’m not optimistic. The definition of an optimist is someone who knows the odds are in their favor. What I am is hopeful. I know the odds are against me, but I’m going to try my best anyway because I know there’s a chance we might be able to turn this around.”

|

||||||||||

Storyteller · Look Again · Thinking Like a Scientist · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Jo Ellen Parker · Artistic License: Out of the Vault · About Town: Let's Talk about Race · Science & Nature: The Body on Stage · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |