|

|||||||||||||||||||

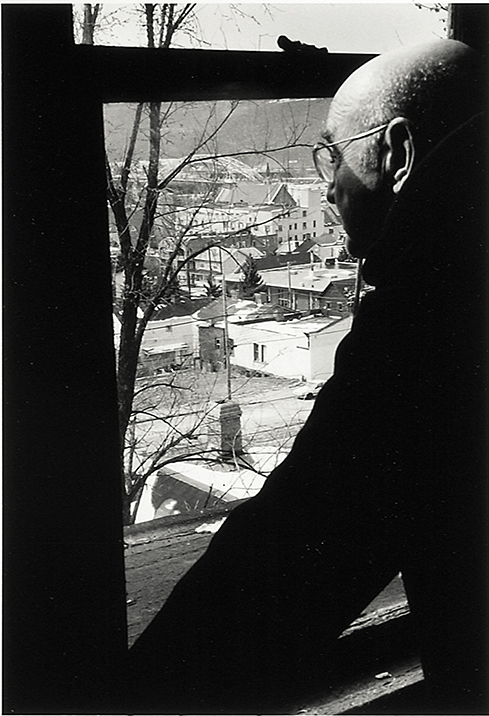

Above: Duane Michals, Grandpa Goes to Heaven, 1989, The Henry L. Hillman Fund |

Storyteller

With a deep-seated reverence for his Pittsburgh roots and a dogged determination to express himself through art, Duane Michals tells his stories his way. At long last, Pittsburgh will celebrate these stories, and the man behind them, through a definitive retrospective at Carnegie Museum of Art.

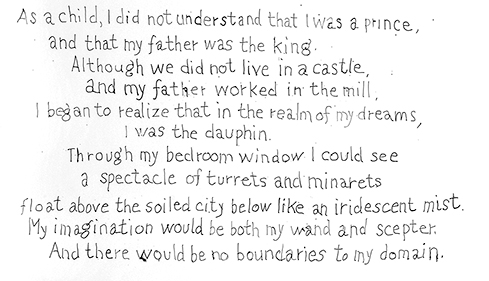

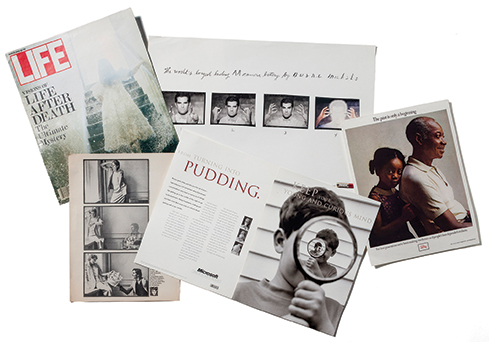

Duane Michals is an 82-year-old world-famous photographer, but as he talks he suddenly transforms into a 7-year-old boy in McKeesport. He recalls one day vividly. He and his mother have ventured inside Cox’s dress shop. His mother finds a chair, plants him there and says, “Stay here. I’ll be right back.” A few minutes later, she loads a few shopping bags onto her little boy’s lap before disappearing into the dress racks again. He sits patiently for five minutes or so. Then panic grips him. Why hasn’t she come back? Has she left me? She returns. But seven decades later, Michals can still feel that childhood fear of abandonment and death—emotions he has channeled into his photographic works. His images about childhood are among his most poignant and, until now, among his most overlooked. They will be exhibited as part of a major retrospective of his work that opens November 1 at Carnegie Museum of Art. Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals showcases six decades of groundbreaking work by an artist who changed modern photography by staging sequences instead of capturing a single moment, and juxtaposing the images with text (handwritten on the margins of his black-andwhite prints). His relentless work ethic, honed from his blue-collar roots, is evident as he explores themes ranging from gender identity to his beloved hometown of Pittsburgh, reinventing himself again and again. “He has created all sorts of wonderful narratives for half a century,” says Linda Benedict-Jones, the museum’s curator of photography and guide to Michals’ long and storied career. “He has a very special place in the history of photography.”

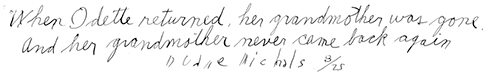

In the artist’s 1992 work Grandmother and Odette Visit the Park, a stern older woman sits on a bench with her granddaughter. “Odette, I want you to sit quiet like a good girl while I read the paper,” Michals penned in the margin. In subsequent images, Odette wanders off and discovers new adventures, including a ride on a merry-go-round. The last frame depicts the girl from behind as she approaches an empty bench. “He uses allegories to show you something that is either quaint or funny or singsongy, and hidden behind it is something sharp,” says Adam Ryan, the museum’s curatorial assistant in photography. “Children get distracted, go out and experience life, and there is the inevitable loss of our parents and our grandparents.” Michals, an admirer and friend of late children’s book author Maurice Sendak (the pair used to walk their dogs together) even wrote a whimsical illustrated children’s book titled Upside Down, Inside Out, and Backwards. But most of his children’s tales are photographic sequences. For Michals, it’s easy to think like a child, even after recently undergoing multiple bypass surgery, a very adult problem. “I am a big kid,” he says, his voice crackling with energy just a few weeks after the operation on his heart. “Grownups don’t do what I do. They leave all this stuff behind. They get rid of it. “Everyone wants to be a grownup. Where does that get you? You cannot do anything in my racket—make art—without being a kid.” PICTURING TRUTHThe older of two sons of Slovak immigrants, Michals was born in 1932 in the then-booming steel town of McKeesport. There was little affection between his stoic steelworker father and his mother, a sales clerk at Kaufmann’s department store. Though Michals remains proud of his father’s hardworking heritage, the two had a strained relationship. In a single image titled A Letter from My Father, he captures a tense profile of his brother, juxtaposed against a head-on view of his father. The patriarch’s hands rest on his hips in a pose of disapproval. In the margin, Michals wrote about a letter he expected from his father after his death, which would reveal the paternal love that was always hidden. The letter never came. The work allowed him to release an outpouring of emotions, and also inspired him to continue writing on photographs, which was considered a sacrilege at the time. For Michals, the writing was never a caption, but a way to pose questions rather than provide answers. Michals knew he didn’t want to work in the steel mills like his father and uncles, and after taking Saturday art classes at Carnegie Museum of Art as a teenager, he saw art as a way out. His parents were encouraging. He loved McKeesport, going to the library, hanging out with friends. He dated girls and never gave much thought to his sexual orientation. “We had sissies in McKeesport in 1949,” he says, letting out his hearty laugh. “We didn’t invent gay people yet.” He studied art on a full scholarship at the University of Denver, graduating with a B.A. in graphic design. He joined the Army, became a second lieutenant and was stationed in Germany during the Korean War. He wrote to his girlfriend in the States but also wrote to a male friend—a turning point in his sexual awakening. (The letters have been published in a book titled The Lieutenant Who Loved His Platoon.) During this period, he would read his well-worn copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, which he bought at Kaufmann’s and kept for years. Whitman’s poetry about his feelings for another man helped legitimize his own homosexuality, and Whitman’s philosophy became a touchstone for Michals’ life. The young artist moved to New York City in the 1950s to make his mark, eventually finding success as a commercial photographer for magazines such as Esquire and Mademoiselle. But he was a self-taught photographer with his own unique voice, influenced most by literature and surrealist painters such as René Magritte, Balthus, and Giorgio de Chirico. (To this day, as museum visitors will discover in the simultaneous exhibition, Duane Michals: Collector, his private art collection contains very few photographs.) At the time, celebrated photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson worked to capture an instant in time, a flash of reality. But the definitive moment was too constraining for Michals. He wanted the moment before and the moment after. So he began staging stories that mined a deeper emotional truth. “He doesn’t believe in the eyes. He believes in the mind.”

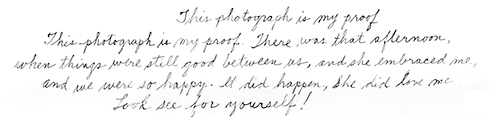

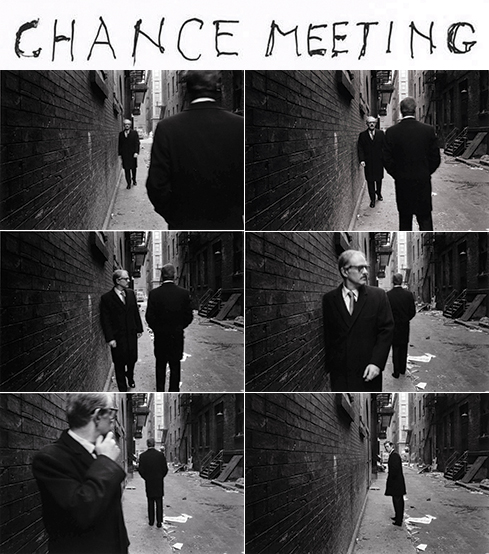

- Linda Benedict-Jones, the Museum of Art's curator of photographyIn 1963, Michals had his first show at the Underground Gallery in Greenwich Village. The works were shockingly different because they included a sequence of images. Photographers Joel Meyerowitz and Garry Winogrand walked out, the latter declaring, “This isn’t photography.” The New York Times also snubbed him, refusing him a review. “It was bigger than the 800-pound gorilla. It was the 999-pound gorilla,” recalls Stephen Perloff, editor of The Photo Review. “It took a long time for institutions to accept this kind of boundary- breaking that Duane and others did. It showed that you didn’t have to create a photograph as a single black-and-white rectangle. It opened the door for other photographers to do similar things to find their own paths.” The backlash stung. “I was surprised by the people with knives,” Michals says. “But it didn’t stop me.” He wasn’t trying to play the part of bad-boy provocateur. “He didn’t do it to be cool and different,” Benedict-Jones says. “He was frustrated with the limitations of the single print.” Among image-makers, Michals is a self-proclaimed anomaly. “He doesn’t believe in the eyes,” Benedict-Jones says. “He believes in the mind.” Michals put it another way. Though some photographs, such as the Hindenburg catching fire, may be worth a thousand words, many others are deceptive. “I could show you a picture of my parents smiling next to each other,” he says. “They didn’t like each other. They hadn’t kissed in 40 years. Photographs lie all the time.” The artist’s career took off after a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1970. One of the standouts was a sequence made that same year, Chance Meeting, which shows two men walking toward each other in an alley. One looks back to see if he knows the other. The second man looks back after the first has turned away. “It involves gay cruising, two guys on the street attracted to each other, passing like ships in the night,” Michals explains.

It’s one of many works in the show that focus on gender. Michals was ahead of his time in exploring gay rights and the struggles of hiding one’s sexual orientation. In The Unfortunate Man, made in 1976, the naked subject arches himself in anguish. Shoes cover his extended hands—a metaphor for being closeted. “The unfortunate man could not touch the one he loved,” reads the accompanying handwritten text. “It was declared illegal by the law. Slowly his fingers became his toes and his hands gradually became feet. He wore shoes on his hands to disguise his pain. It never occurs to him to break the law.”

PICTURING HOMELike Andy Warhol, Michals escaped his blue-collar Pittsburgh roots and moved to the epicenter of art production. Unlike Warhol, he cherishes western Pennsylvania, returning at every opportunity for high school reunions, to visit Carnegie Museum of Art and other favorite haunts, and to photograph the city that still defines him. “I still have this umbilical cord to western Pennsylvania,” Michals proudly admits. “Most people are so anxious to leave home. I have run away many times, but I have never left. It’s my spiritual home.” While describing his next trip back for the museum retrospective, he quips about gussying himself up for the occasion. “I think I will get a face job while I’m at it.” His photographs of his hometown—a lynchpin of his upcoming retrospective—are honest and intimate, a kind of photographic memoir. The House I Once Called Home depicts the abandoned three-story brick house on High Street where Michals was born. That bleak image is juxtaposed with scenes from his childhood, when the same home bustled with the energy of his family. “There is something very moving seeing how the space that once was alive with his parents and grandparents and him and his brother is now lost to decay,” Perloff says. The 30-work sequence will be on view in its entirety for the first time outside of New York City. “I still have this umbilical cord to western Pennsylvania. Most people are so anxious to leave home. I have run away many times, but I have never left. It’s my spiritual home.”

- Duane MichalsOther examples of his work capture the city from unusual angles. A sequence titled Old Money shows the graves of industrialists Henry Clay Frick, Willard Rockwell, and members of the Mellon family in Homewood Cemetery (a place Michals jokes would never allow him into its hallowed tombs). “This is where everyone ends up,” he says. “Even the Mellons die. Ultimately, this is the trip we take, rich or poor.” Six Views of the Cathedral of Learning in the Manner of Hiroshige shows the classroom tower at the University of Pittsburgh from six unique angles—from a moving vehicle to a far-away window reflection—an homage to 19th-century Japanese woodblock prints that featured famous views in the countryside. REINVENTINGThe retrospective—the largest ever representation of Michals’ work, including recent works rarely seen by the public—also features many portraits, which he has recently dubbed “prose portraits.” “You can’t capture someone, per se,” Michals insists. “How could you? The subject probably doesn’t even know who the photographer is. So, for me, a prose portrait is about a person, rather than of a person.”

His portraits feature a variety of subjects, many well-known, including Meryl Streep, Sting, Willem de Kooning, and Magritte, as well as the unknown, including the subject of Black is Ugly. This 1974 work presents a profile of an elderly black man in a suit, looking out a softly-lit window. The simple accompanying text allows for interpretation that the image alone could never achieve. “It’s as if the man could embody all elderly African Americans in the early 1970s, who had come of age before the Civil Rights Era,” notes Benedict-Jones. “The image illustrates Michals’ deep empathy for those who, because of a lifetime of exposure to the lies white men had told them, didn’t know how to trust the popular motto of the 1960s cultural movement, ‘Black Is Beautiful,’” she adds. “The image and text work together to make a poignant statement about race relations in the United States.” Michals keeps reinventing himself. He gets bored with artists who follow formulas in the hope of becoming superstars. “I have almost nothing to do with the New York art world,” he says. “There are these artists who developed a style. They become a brand. Buy the Warhol brand.”

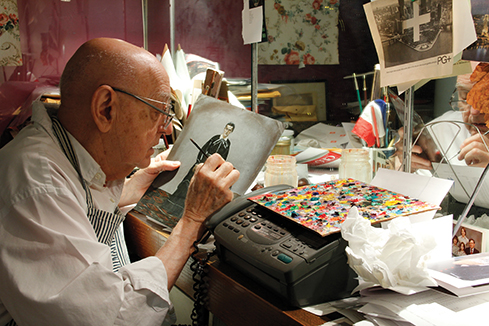

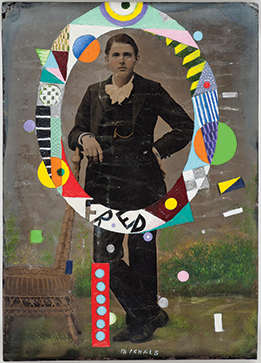

As part of his own evolution, in 2012 Michals began hand painting on found tintypes— oversized, unique photographs created on a thin sheet of iron, a popular portrait format in the second half of the 19th century. In Rigamarole, he rendered an ornate crest with the name Fred on a 19th-century tintype. It’s a tribute to Fred Gorrée, his partner of 54 years. The pair married in 2011, just nine days after same-sex marriage was legalized in New York. Despite some post-surgery downtime this past summer, the prolific artist is itching to get out of bed and continue reinterpreting the world in his own way. “In the back of my mind, I have a new idea,” he says. “That is always very exciting.”

|

||||||||||||||||||

Shock and Awe · Look Again · Thinking Like a Scientist · Director's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Jo Ellen Parker · Artistic License: Out of the Vault · About Town: Let's Talk about Race · Science & Nature: The Body on Stage · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |