Since March, Thaddeus Mosley has created six stunning sculptures, one soaring high above him, another comprised mostly of reimagined “cut-offs,” which are the removed ends of wooden logs that have been trimmed to achieve a straight edge.

Inspired by the shape of raw wood, he uses a mallet and gouges to reduce often massive tree trunks, chip by chip, letting them speak through the revealing of forms. “The log and I decide together what it will become,” says Mosley, noting that he lives with each trunk, getting to know it—its grain, its structure, its unique personality—before picking up any tools.

At age 91, the celebrated Pittsburgh artist is developing new work for the 2018 Carnegie International, the 57th edition of Carnegie Museum of Art’s signature exhibition that dates back to 1896. Most of the sculptures, made low to the ground and treated to withstand wind and moisture, will be displayed outside in the museum’s Sculpture Garden. Existing work carved over decades—one piece measuring nearly 14-feet-tall—will be shown inside.

Above, Thaddeus Mosley inside his North Side studio. Below is a glimpse of the dozens of sculptures that flank him as he works. The images were captured by the Mattress Factory in advance of Mosley’s 2009 exhibition there, Thaddeus Mosley: Sculpture (Studio|Home).

Renowned for his energy and work ethic, the self-taught artist works at a pace that, even at his age, hasn’t changed all that much in decades. In mid-life, Mosley would carve for eight hours a day after working his full-time night job at the U.S. Postal Service—a stable “means to an end” position he held for 40 years while raising six kids—and 12 hours a day on weekends. Today, he spends five to seven hours a day in his rented basement studio on the North Side, working creatively among a forest of sculptures, a few nearly twice his size. Occasionally, he takes a break on a Sunday to visit family. “I work faster now, but I worked longer when I was younger,” says Mosley.

Turning wood and stone into art is not a fast process. Many of Mosley’s sculptures include four or five components, some weighing more than 100 pounds each. A large work usually takes him a month or two to complete; some take up to four.

“My studio makes me want to work,” says Mosley, whose compact, muscular build hints at the vigor needed to coax his sculptures to life. “At night, I’m thinking about what I’m going to do the next day. I always believe I’m going to do something better than I’ve done before. Maybe it doesn’t happen, but it’s a challenge, and I find satisfaction in it. I have a sense of urgency while I’m able to do it.”

In a way, his participation in the Carnegie International, opening next October, means he’s come full circle. Carnegie Museum of Art was the New Castle native’s informal art school—the place where, while studying journalism and English at nearby University of Pittsburgh in the late 1940s, he fell in love with art. At a painter friend’s prompting, “We would spend a lot of time in the collection just looking, looking at certain pieces from every angle to figure out how they were made,” he recounts. “I think sometimes we looked so long and hard the guards thought we were looking to remove a big bronze or something,” he says, laughing.

“Looking is how we learned. And that’s what I tell people starting in sculpture. Thinking in the round takes a lot of looking, and looking hard until you get a feel for it.”

Mosley is a student of the International, having attended every iteration since the 1950s, when, following World War II, it emerged as an influential show of the avant-garde, documenting the rise of significant developments such as abstract expressionism. In the ’50s, jurors included Marcel Duchamp and Vincent Price. The museum purchased works by Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline for its collection.

“My studio makes me want to work. At night, I’m thinking about what I’m going to do the next day. I always believe I’m going to do something better than I’ve done before. Maybe it doesn’t happen, but it’s a challenge, and I find satisfaction in it.”

“I couldn’t wait to see what surprises were in store,” says Mosley, noting in those days people went to the show’s openings as much to see the artists as the art. “The Internationals were one of my big joys, especially in the ’50s and ’60s. You got to see things you would never see any other time—work from Borneo, China, Bali, South America. They’re among my favorite memories of learning about art—you would see such a wide range of stuff in one show.”

Next year, he’ll be one of those surprises. “It’s like, I guess, the little league baseball player finally becoming a major leaguer,” he says, using an analogy befitting a former sports reporter.

An awakening

Born to a coal miner father and a seamstress mother, Mosley graduated from New Castle High School with honors and as class president in 1945, and was drafted into a segregated Navy, stationed first in Illinois and then the Western Pacific. He was 20 when he was demobilized and entered Pitt, where the only blacks employed by the university were service workers.

With plans to be a magazine writer, Mosley registered as a dual English and journalism major, prompting the English department’s dean to call him to his office. “He told me he was curious about an Afro-American wanting to major in English.” When Mosley responded with the names of famous black writers and colleges, the administrator seemed completely unfamiliar with them. “That was curious to me,” he says. “But people didn’t want to know because they didn’t want anything to disrupt their conclusions that they had about your inability.”

A book assigned in a world history class changed the trajectory of his life. In it, he discovered a sculpture by Romanian artist Constantin Brâncuși. Displayed directly across from it was a sculpture by an unknown African sculptor.

“It was 1948 and I had never seen a piece of African tribal art,” recalls Mosley. “It was paired with Brâncuși’s art. I was stunned by seeing this even though I wasn’t an artist. It just blew me away.”

Joined by Japanese-American artist and landscape architect Isamu Noguchi, whose work Mosley admired in five Internationals, Brâncuși and African tribal art remain Mosley’s deepest influences. He carved his first sculptures about five years later, at the age of 28, following a trip to Kaufmann’s department store in downtown Pittsburgh.

At the time, Scandinavian furniture was all the rage, and displayed with it at Kaufmann’s were petite wood carvings of birds and fish. “They wanted $75 for one and $125 for another, and in the 1950s that was a lot more money than it is now. I looked at them and thought to myself, ‘Heck, I can do that,’” says Mosley, smiling his laid-back smile, chuckling at himself. “I picked up a couple of 2-by-4s and made mine bigger and fatter than the Scandinavian ones.

“My art started because I wanted it for my house. I’ve always made things for myself. Still do.”

By that time, he was married with a family, and was covering high school and college sports 20 to 30 hours a week, sometimes more, for the Pittsburgh Courier, while also working at the post office. Eventually he gave up the reporting to focus his free time on making art.

He and other artist friends showed their work in their Hill District community whenever and wherever they could—in parks, on porches, and in garages, usually on Sundays to catch the after-church crowds. In 1959, he entered his first juried show at the Three Rivers Arts Festival. Jerry Caplan, a sculptor who taught at Chatham University, saw his work and encouraged him to join the Society of Sculptors, which he did, as well as the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh.

William Palmer (left) and Thaddeus Mosley with their work at the Three Rivers Arts Festival in 1959—a moment, captured by Teenie Harris, marking Mosley’s first juried show.

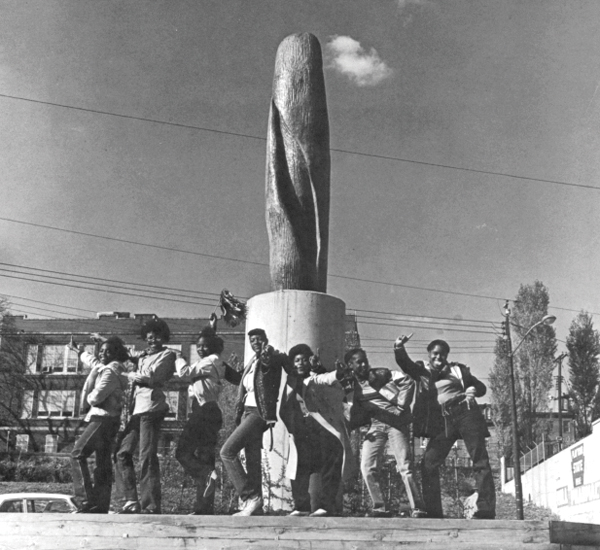

Community members pose with the Phoenix in 1979.

In 1966, then Carnegie Museum of Art director Leon Arkus offered him a one-man show. With few galleries in Pittsburgh at the time, it was a coveted honor. Featuring eight sculptures, the exhibition opened in 1968, right around the time Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Violence erupted in cities across the country, including in the predominantly black neighborhoods in Pittsburgh, and some local protesters called on black artists to refuse to show their work in white institutions like Carnegie Museum of Art.

Mosley, who had protested discriminatory hiring practices at places like Duquesne Light and U.S. Steel, forged ahead, and the show’s success led to more recognition. In 1979, he was named Artist of the Year by the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts—all while still working full-time at the post office. He also taught summer classes in wood sculpture for 28 years at the Touchstone Center for Crafts in Fayette County. In 1992, he was able to retire from “the drudge work” of sorting mail and five years later had another solo show at the museum.

What is it about wood? “It was free and available,” explains Mosley, noting in the early days he could get his hands on it easily through nearby public works departments. He grew to love its warmth, its colors, and the texture of hardwoods, using mostly walnut, wild cherry, and elm.

In his sculptures, the artist conveys a sense “of levitation, a feeling of movement as you walk around them. They should look and feel like they’re floating,” he explains, “and the emphasis is up instead of down,” with the most weight at the top of sculpture, not the bottom. Including multiple components, his creations are built to be disassembled, transported, and reassembled.

“Looking is how we learned. And that’s what I tell people starting in sculpture. Thinking in the round takes a lot of looking, and looking hard until you get a feel for it.”

A rhythm to the work

A beloved elder of Pittsburgh’s art community, Mosley contributes to his city in the same way he’s lived his life: with an abundance of generosity and modesty, and leading by example.

Says artist Diane Samuels, a longtime friend and Mexican War Streets neighbor of Mosley’s who also owns one of his large sculptures: “Years ago, I must have been in New York, and I saw Mikhail Baryshnikov just walking down the street, and I looked at him and it wasn’t that I recognized Baryshnikov right away, but I thought, ‘God, that man isn’t walking, he’s dancing.’ Then I realized who it was. I didn’t say anything to him, but I thought, ‘There is something about completely integrating your art, your body, your philosophy, the brilliance of your art, they’re all one.’

“Thad’s been doing it all these years, but it’s not like ‘Oh, I have to do this.’ It’s more there’s an internal reason why he has to do it.

Mosley in his art-filled home in the Mexican War Streets. Photo: the Mattress Factory

“It’s wonderful that he’s being acknowledged in a very big way now, but Thad’s always been a really great artist—40 years ago, 50 years ago. His artwork, it’s got a really clear vision. The man expresses—in his work and in his self—extraordinary joy about the making and about the thinking that goes into the artwork. He’s an inspiration to many people from that point of view. He’s just kept on, and kept on, and kept on.”

Mosley credits some of the discipline and much of the improvisation in his work to the fact that he came from a musical family. His father played the trumpet and his mother and all four of his sisters played piano, two seriously. He sang a cappella for three years in high school. In 1934, he started listening to jazz, and came up during the heyday of Pittsburgh’s legendary jazz clubs on the North Side and in the Hill District.

“Jazz was part of the all-around culture of my life,” he explained to a group of museum patrons in late September. They’d come to sketch as part of the International’s Tam O’Shanter drawing program, this particular iteration inspired by a jazz playlist culled from Mosley’s personal collection highlighting Pittsburgh legends Sarah Vaughan, Erroll Garner, and Billy Eckstine, set to a slideshow of his work.

Transporter of Fire, 1998, walnut and steel

“Thaddeus is working in a modernist tradition and that sort of space of abstraction —rhythm, form—that he equates very directly to music,” says Ingrid Schaffner, curator of the 2018 Carnegie International.

He’s an active participant in the local jazz scene, spending every Thursday night listening to jazz great and lifelong friend Roger Humphries jam at the James Street Gastropub and Speakeasy on the North Side, before it announced recently its closing. “It’s my religious observance,” says Mosley. “Roger is one of the last of the greats of a legion of great drummers to come out of Pittsburgh. He takes me back to the old days when jazz really flourished.”

Humphries sees the rhythm and improvisation of his craft reflected in his friend’s sculptures. “It’s very creative, you can’t necessarily define it, but you can see it, feel it,” says Humphries about the ripples and the contrast they create in the carved wood.

Over six decades, Mosley estimates he’s made about 700 sculptures, large and small, both in stone and wood. One of his most well-known works, the Phoenix, sits at the corner of Centre Avenue at Dinwiddie Street in the Hill District, signifying the community’s rising from the ashes of the fires set during the civil rights riots of the 1960s. Another, Georgia Gate, was acquired by Carnegie Museum of Art in 1976 and is currently on view as part of 20/20: The Studio Museum in Harlem and Carnegie Museum of Art.

Thaddeus Mosley’s Georgia Gate (at right), created in 1975 and acquired by Carnegie Museum of Art the following year, is currently on view as part of 20/20: The Studio Museum in Harlem and Carnegie Museum of Art.

More than 100 others surround him in his studio, and he lives among another 60 to 70 at his modest home, which is also filled with books—art titles, poetry, a hardback he’s currently reading about astrophysics —as well as his treasured collection of African tribal art, and many creations by friends in the local art community that he relishes.

His work, as is his life, is an accumulation.

“Thaddeus’ work has been in conversation with the Carnegie International for decades,” says Schaffner, “through what he’s brought back to the studio from the exhibitions, and now because he’s part of it. To encounter one of Thaddeus’ sculptures is very satisfying, and you feel that it’s part of a larger body of work. It’s not only about the singular object, but about a world of work you’re brought into.”