Just about every Saturday night from 1977 to 1986, people across America would anchor themselves to their living-room couches and cast their attention to the family television set. The Love Boat was on. An unabashed prime-time sensation, it offered viewers a weekly dose of celebrity trolling that almost rivals any Twitter feed.

“Love, exciting and new,” the familiar theme song would croon as the credits announced each episode’s passengers, played mostly by former stars relegated to less-than-stellar guest stints. “Come aboard, we’re expecting you.”

On one particular Saturday night—October 12, 1985, to be precise— something equal parts weird and wonderful happened. Along with Milton Berle, Tom Bosley, Andy Griffith, Cloris Leachman, and Marion Ross, the 200th installment of the series also featured Andy Warhol.

He played himself. Art imitating life. Life imitating art. Both satire and homage. At least that’s what The New York Times thought. In a 1991 article previewing the opening of a Warhol exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the paper referred to his Love Boat performance as “either the kitschy high point or the banal dregs.”

The article went on to say, “Warhol’s iconic silkscreen portraits of Elizabeth Taylor and a low-brow hit television series were a perfectly natural combination, at least for the artist who in the 1960s painted a Campbell’s soup can and almost single-handedly demolished the barriers between popular culture and high art.”

It’s exactly those themes—Warhol’s humanity, his contradictions, his obsession with fame and celebrity as well as his own fame and celebrity—that come into focus in a major new exhibition opening June 16 at The Andy Warhol Museum.

Soon after her tragic death in 1962, Andy Warhol made a series of paintings paying tribute to Marilyn Monroe. He used this publicity still taken by Gene Kornman for the 1953 film Niagara as his source material. The crop markings are Warhol’s. Photograph (Marilyn Monroe), ca. 1953, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Boasting nearly 900 items and spanning four decades, Andy Warhol: Stars of the Silver Screen debuted at the TIFF Bell Lightbox of the Toronto International Film Festival in October 2015. It’s been expanded for its Pittsburgh showing, highlighting even more of the native son’s artworks and the inspiration behind them. The show marks the first time much of the art and artifacts will be seen together, creating a fuller, more vibrant picture of both Warhol the artist and Warhol the fan, says Geralyn Huxley, the museum’s curator of film and video and the architect of the show, in partnership with Matt Wrbican, The Warhol’s archival consultant and former chief archivist .

Among the show’s treasures: Warhol’s early experiments with rubber-stamp multiples and composites; source materials for several of his most famous celebrity portraits; clips from movies filmed at The Factory; and selections from his series of silent-film portraits, Screen Tests. This deep dive also includes Interview magazines, segments of episodes from all three of his cable television shows, and of course his Pop portraits, prints, drawings, and Polaroids used as the foundation for silkscreens .

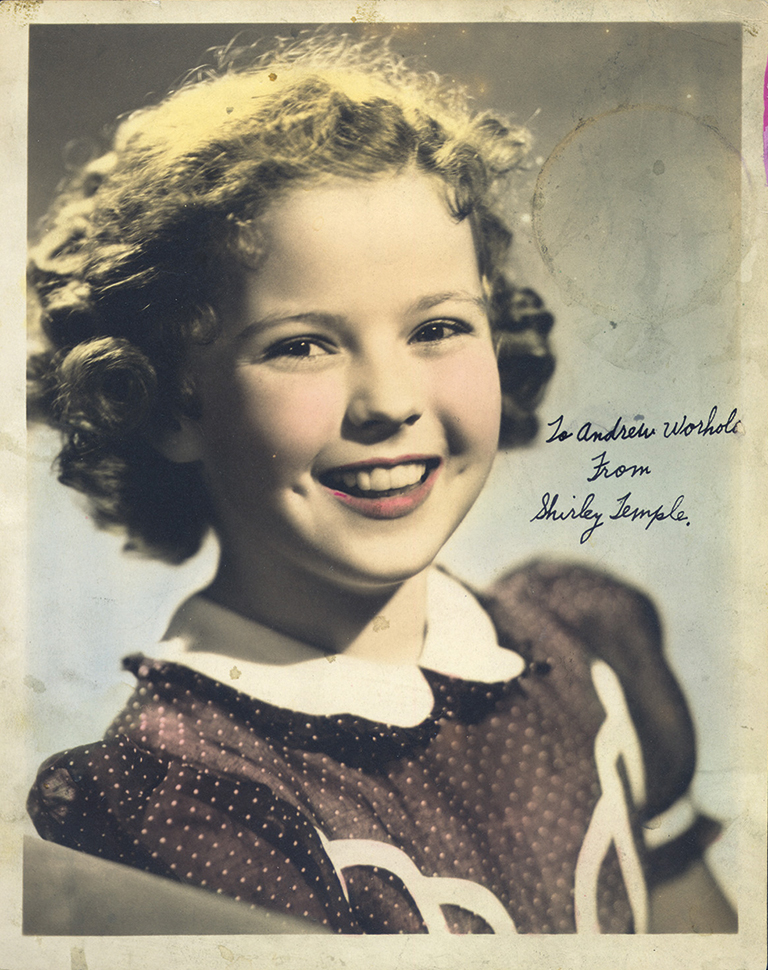

Shirley Temple, 1941, The Andy Warhol Museum, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Also on display will be objects from the artist-slash-packrat’s vast personal cache, including his prized childhood scrapbook featuring his screen idols, memorabilia he gathered throughout his life such as studio publicity shots, paper dolls, and costumes; fanzines; and correspondence from stars themselves, including one of his favorite stars, Shirley Temple, who was his same age and misspelled his name in a personalized message to him. Warhol’s oft-quoted statement, “I never wanted to be a painter; I wanted to be a tap-dancer” is most likely a reference to the work of the child actor he adored.

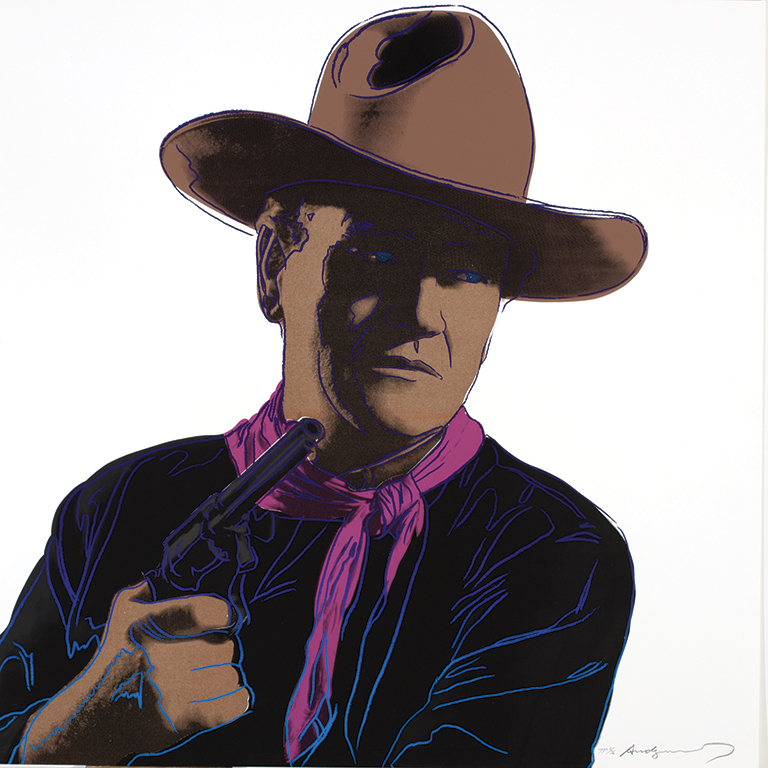

While immersed in Warhol’s world, visitors to the exhibition can expect plenty of celebrity sightings. Marilyn and Liz will be there, as well as a who’s-who list including Brigitte Bardot, Ingrid Bergman, Joan Collins, James Dean, Elvis, Jane Fonda, Greta Garbo, Judy Garland, Grace Kelly, Liza Minnelli, Ronald Reagan, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and John Wayne, to name just a few. “Andy has been portrayed in culture in a very 2-D way,” Huxley says. “But with shows like this we can really utilize The Warhol’s archives to reveal multidimensional aspects of him that people might never suspect were there .

“He was very creative and worked constantly,” she adds. “He had many sources of inspiration, and the show concentrates on the huge influence that Hollywood and celebrity culture had on him.”

In his Cowboys and Indians series, Warhol couples recognizable portraits of well-known American “heroes”—John Wayne and Annie Oakley among them—with less familiar Native American images and motifs in his ironic commentary on Americans’ collective mythologizing of the historic West. Andy Warhol, Cowboys and Indians: John Wayne, 1986, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

THE ALLURE OF GLITZ AND GLAM

One of the great things about movie stars during the glory days of the big Hollywood studios in the ’30s and ’40s is that they were ubiquitous. Their larger-than-life personas could be seen in every theater in every town throughout the country.

Like a lot of kids growing up during the Great Depression and then World War II, Warhol and his older brothers Paul and John found refuge in the neighborhood cinemas near their South Oakland duplex. As soon as the lights dimmed, the stars of the day—Shirley Temple, Clark Gable, and Joan Crawford—would carry them far away from their daily routines .

A sickly and shy boy, Warhol embraced the icons he saw on the big screen. By age 11, he was amassing autographed photos, cutting out images from magazines, and then ever so carefully arranging them in his cardboard album. This act of reverence would later be replicated in his famous silkscreened celebrity grids and even play a supporting role at the scene of his death in 1987 .

As Huxley tells it, “There was a small photo of Frank Sinatra mounted in his childhood scrapbook, and there in his hospital room when he died was the Kitty Kelley bio His Way: The Unauthorized Biography of Frank Sinatra.”

“Warhol took the things he was interested in and made them into art.”

– Geralyn Huxley, curator of film and video at The Warhol

Call it the circle of life, if that life happened to revolve around the enigma of fame. Of course, fame was something Warhol found in his own right. After moving to New York in 1949, he slowly but surely began to cultivate a following. He became the essence of cool in the ’60s. His signature look: Ray-Ban sunglasses, black leather jacket, and white-blond hair made him instantly recognizable. And his art—the Campbell’s Soup Can series, the celebrity portraits, his films, and the opening of The Factory, his work space and a place to see and be seen—launched him into the firmament.

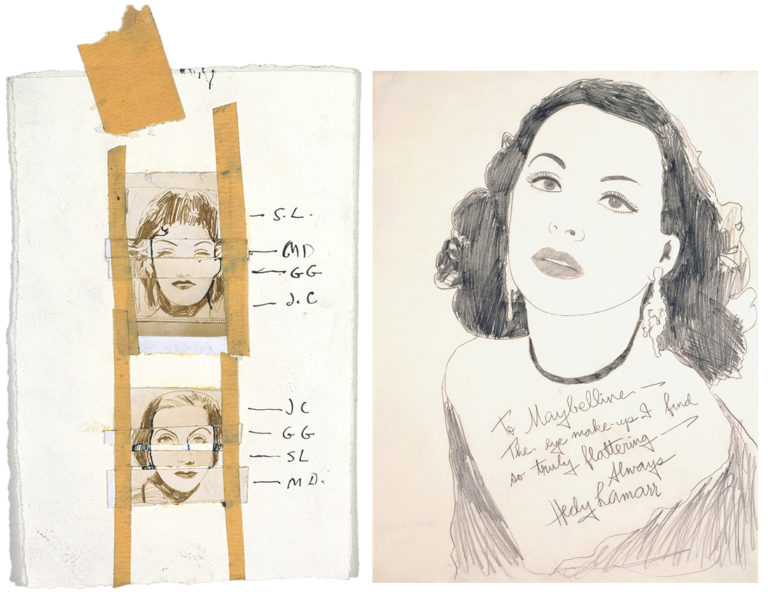

But he was always an artist first. “Warhol took the things he was interested in and made them into art,” Huxley says. “He cast a wide net for ideas, and when he found something he liked he worked with it, oftentimes repeatedly—either in printing multiples or by returning to subjects years later.” He made a graphite drawing of Hedy Lamarr’s 1945 Maybelline magazine ad, for instance, then later, he made a film, Hedy, starring his own Superstar actors after Lamarr had been arrested for shoplifting in 1966.

In this 1962 collage, Andy Warhol cut and glued strips of various celebrity facial attributes to create a single image. The same year he made a graphite drawing of Hedy Lamarr’s 1945 Maybelline magazine ad.

Andy Warhol, Female Movie Star Composite, ca. 1962, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. Andy Warhol, Hedy Lamarr, 1962, The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

What he liked, says Huxley, was the mundane, the ordinary things that populated everyday life. And as Hollywood’s studio system broke down, celebrities seemed to become more and more “ordinary,” at least in the sense that we could watch them on television, read about them in the newspaper, and witness their frailties and scandals with ever-increasing regularity. In that way, she says, “The stars became Pop.”

THE SUPERSTAR FACTORY

Basically, the business of fame was evolving into an equal-opportunity employer—and Warhol was the HR person. He would seek out emerging actors of the day, from Farrah Fawcett to Brooke Shields, and add them to his soon-to-be vast Polaroid collection. And by collaborating with counter-culture and avant-garde artists such as Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground and Jean-Michel Basquiat, he no doubt enhanced their appeal .

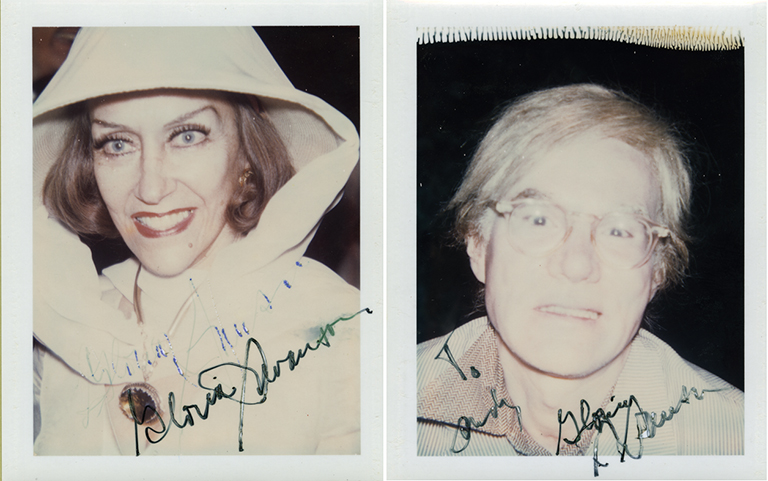

So, it’s not without irony that Toronto’s The Globe and Mail asked, “What was The Factory, with its stable of ‘superstars’ such as Viva and Edie [Sedgwick], Ondine and Mario [Montez], but a sort of parallel to, and low-rent parody of, the Hollywood studio system that so brightened Warhol’s benighted childhood?” But even when his star was on the rise, Warhol could still be starstruck. At a 1972 party commemorating the 60th anniversary of Paramount Pictures, he came face-to-face with the legendary Gloria Swanson. Not surprisingly, he took a Polaroid of her; and she, in turn, took one of him. His expression is pure adoration.

At a 1972 party celebrating 60 years of Paramount Pictures, Gloria Swanson and Andy Warhol snapped Polaroids of one another.

“He was always taking pictures,” Huxley says, noting that the famous pair of snapshots is on view in Stars of the Silver Screen. “He also used a tape recorder for a long time, frequently audiotaping people. When a new technology popped up, he embraced it. When the Sony Walkman came out, he immediately got a Sony Walkman. He made movies in 16mm, then when consumer grade video came out he started working with video and later purchased more professional equipment to make his own television series. Towards the end of his life, he had a Commodore Computer and was making art with the Amiga [a mid-’80s competitor to Apple’s Macintosh.]

“He loved cable TV,” she notes, adding that what he really prized was the promise of cable television—its intimacy, its immediacy, its egalitarianism. And so goes the now-famous quote: “In the future,” Warhol quipped, “everybody will be world-famous for 15 minutes.”

This singular statement, says The Globe and Mail, “was at heart a recognition of the power of mass media and popular culture to weirdly democratize the manufacture of glamour and celebrity.” When filtered through today’s omnipresent social media lens, Warhol’s assertion seems ever more prescient .

Many have proclaimed he was the original Hollywood-obsessed, selfie-addicted, multi-media-sampling, collaborative content creator. Given that context, Stars of the Silver Screen might play more like Back to the Future than Gone with the Wind.

“The entire exhibition is tiled with his collection of framed publicity portraits of celebrities, from Hedy Lamarr to Warren Beatty and beyond,” wrote The Toronto Star. “Warhol collected these obsessively, and they fit the frame through which he viewed his art: mass-produced, consumable bits, designed to idealize and not to reveal.” But in Huxley’s estimation, Warhol’s work is quite revealing. “I think the role of art is to help you learn things about yourself that you don’t already know,” she says .

As for Warhol’s own public persona, it was always a work in progress. “The wig was an artifice,” says Huxley. “He was very shy and would hide behind people. He wasn’t in his films much at all. In 1979, when his first television show started, he was in only a couple episodes, but by the last show in the ’80s he was the full-fledged host. Also in the ’80s, he joined the Ford and Zoli modeling agencies and was doing runway shows.

“He was growing as an individual,” she says. “That’s what human beings do.”

Andy Warhol: Stars of the Silver Screen is supported by Cadillac.