Nona Faustine sat inside her Brooklyn apartment, watching TV as she recovered from COVID-19. Exhausted from the lingering effects of the virus, the photographer had no intention of making art that day—June 1, 2020—until she saw something so startling that she instinctively jumped to her feet and grabbed her camera. There was President Trump, holding a Bible, in front of Washington, D.C.’s historic St. John’s Episcopal Church.

She snapped a still of the now-infamous image that would appear in newspapers and on TV screens across America—the Bible-toting president juxtaposed against federal troops who had cleared his way from the White House to the church by throwing tear gas at people peacefully protesting police brutality and the murder of George Floyd. “When he held up that Bible, I was like, ‘Oh, my God,’” Faustine recalls. “He did it as a photo op. He probably never even opened the Bible before. To me, it summed up everything that was going on in the nation.”

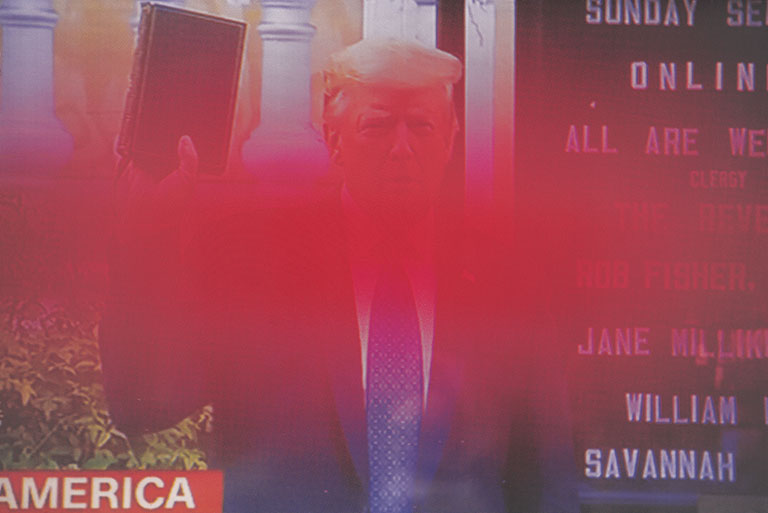

Faustine homed in on the president and the Bible he placed not far from his face. Through her camera she slashed the scene with a thick red line, just below Trump’s face, and silkscreened the image at 60 inches by 40 inches. Also caught on camera, the word “America” at the bottom edge of the screen in all caps, the first “A” partly lopped off. Intentionally obscured is part of the church’s placard, making the message All are welcome here unreadable. Titled Oh No The Devil Never Ever Lies, the work will be on view for the first time as part of Fantasy America, a new exhibition at The Andy Warhol Museum featuring five artists whose work reflects contemporary American life. It opens March 5 and runs through August 30.

Nona Faustine, Oh No The Devil Never Ever Lies, 2020, Courtesy of the artist and Two Palms © Nona Faustine

The work is one of nine silkscreens from Faustine’s ongoing series My Country, which reframes iconic American monuments, to be displayed against the backdrop of Andy Warhol’s wallpaper featuring the Washington Monument. It’s a moment not lost on Faustine. “Even as a kid, I loved Warhol,” she says. “I am over the moon. Warhol is like a god. This is the closest thing to meeting him.”

Faustine and four other emerging contemporary artists—Kambui Olujimi, Pacifico Silano, Naama Tsabar, and Chloe Wise—were invited by José Carlos Diaz, The Warhol’s chief curator, to use Warhol’s travelogue-style book, America, as a jumping-off point for creating their own interpretations of the United States. Mimicking the punk zines of the 1970s and 1980s, Warhol’s 1985 publication is a scrapbook of sorts of the decade he spent meandering around the country snapping black-and-white photos, interspersed with his musings about everything from fame to glamour to immigration and homelessness.

Diaz came up with the concept for Fantasy America after reading a passage from the book in which Warhol wrote, uncharacteristically, of his own childhood in Pittsburgh: “Everybody has their own America, and then they have the pieces of a fantasy America they think is out there but they can’t see.”

Published two years before Warhol’s death, the book was a bit of a bust. But Diaz saw in it an opportunity. The cover of the book’s first edition shows an image of the Statue of Liberty surrounded by scaffolding for its centennial celebration. Now, five young artists reflect on their own current-day America, in the process exploring a range of subjects from modern injustices to intimacy, joy, and consumerism. Tethered to a present moment of political upheaval, social unrest, and a global health crisis, the 32 works in the show highlight what America is and what it can become, says Diaz.

“Everybody has their own America, and then they have the pieces of a fantasy America they think is out there but they can’t see.”

– Andy Warhol

“This show is about life in America from the perspective of artists: the good, the bad, and the ugly. From personal to Pop to political, these artists have examined our culture for quite some time,” he says.

“I chose these five because I have been watching them closely between a span of five to 12 years and thought they would complement one another in a show about artists working in America, at this moment.”

The artists share many Warholian characteristics. They work across various disciplines and media, address popular culture, and frequently use visual repetition in their artmaking.

“During his time, especially later in life, Warhol was supportive of the next generation of artists,” says Diaz. “That got me thinking of Warhol’s legacy and his heirs. The show is made up of New York-based artists. They’re not all American, but they have planted roots in New York City, like Warhol. They are all talking about their lived experience and identity in the United States. These are artists that you will continue to read about and see in the future.”

The weight of systemic racism

Kambui Olujimi’s eclectic artmaking explores the decolonization of bodies, land, time, and space. And like Faustine’s work, it surfaces political pasts.

In a new body of work titled North Star, he uses weightlessness to represent freedom in large ink drawings that show Black people twisting and turning as they float in abstract space. Two new pieces will be on view in Fantasy America.

“One of the things I’ve been thinking about is the gravity of white supremacy and oppression,” says Olujimi. “It’s thought of as this inevitability, and this model says that weightlessness is a temporary escape from this.

“What is the Black body in zero gravity? What does it look like? This project really puts that out there. And it’s a meditational weightlessness. … It’s really about this description of freedom and who gets to be free. When you’re born, you’re born free. And then there are systems that work to take that away immediately. The weightless body is no longer weighed down by these systematic things.”

Kambui Olujimi, Hand to Hand, 2020, Courtesy of the artist

Olujimi plans to go beyond imagined weightlessness to lived experiences. He launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise money to conduct parabolic flights—maneuvers in which a specially trained pilot flies in a steep arc to reproduce the sensation of zero gravity for passengers. “It’s like a 30,000-foot roller coaster,” he says.

He plans to take a small group of people from the African diaspora on the flights and document their experiences of weightlessness.

While the flight experiment is delayed because of the pandemic, Olujimi has continued to pour his intense creative impulses into other projects, including a small-scale series of Quarantine Paintings that address violence in Minneapolis and Kenosha, among other topics. At midnight each day this past September, his video In Your Absence the Skies Are All the Same, which combines footage of skies from around the world, was illuminated on the giant screens of Times Square.

His 2017 work T-minus Ø, on view in Fantasy America, is a series of 13 flags mounted to a wall. But instead of representing different nations, the flags carry printed images—layered, edited, repeated—of failed American rocket and shuttle launches as commentary on the conquest of space.

“What is the cost of space exploration, the narrative of conquest?” Olujimi asks. “These landscapes are really beautiful and sublime but extremely tragic and traumatic. A lot of people remember those explosions and disasters.”

What would Warhol say?

Some work in Fantasy America is presented in direct conversation with art by Warhol. Fellow queer artist Pacifico Silano uses vintage gay porn magazines to collage what he calls arrangements. These works present a new narrative, often about love and loss, with some rooted in the AIDS crisis while also speaking to the current pandemic. In his 2019 work The Meat Rack, he includes an image of a cowboy hat on a branch, the body it belongs to out of frame. In displaying it and another photographed collage alongside a pair of Warhol portraits of actor Dennis Hopper, the Pop artist’s movie star pal, Silano explores the American cowboy trope and its associations in queer culture.

Pacifico Silano, Sure of You, 2019, Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Julie K. Herman

Similarly, Diaz pairs performance artist Naama Tsabar’s Stranger, a video work featuring two female musicians negotiating the use of a shared instrument, a custom silver double-guitar, with a Warhol 1962 Dance Diagram painting that reproduced popular dance steps onto canvas. “Tsabar’s work branches from live music and the spaces where we experience it, often in crowded, intimate venues and after dark,” says Diaz. “Warhol understood the liberation of music and nightlife.”

Naama Tsabar, Stranger (video still), 2017, single channel video, Courtesy of the artist

Some contributors take up similar themes as Warhol. Chloe Wise, a painter, sculptor, and video artist with a large following on Instagram, confronts American consumerism and social rituals in her work. Fashion and food are among her chosen subjects. Early in her career she slapped Chanel and Prada hardware on what she calls “bread bags”—casted urethane sculptures of purses and backpacks made to look like real bagels and jelly-slathered toast.

Chloe Wise, Tormentedly Untainted, 2019, Courtesy of the artist © 2019 Chloe Wise/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fantasy America highlights a range of video works by Wise, including her 2020 video Alternative Facts. In it, a television sits on the beach, the vast ocean behind it, the artist’s face on the screen. She looks like a disembodied head on the sand as she recites the words of Kellyanne Conway, President Trump’s former adviser who coined the term “alternative facts.” In front of the television screen, another Chloe Wise, laying on the sand, stares at herself speaking and possibly accepting what she hears herself recite.

Chloe Wise, Alternative Facts, 2020, digital film, Courtesy of the artist

“It looks and sounds humorous, but it’s actually verbatim from the words that came out of Kellyanne Conway’s mouth. It’s playful yet disturbing,” says Diaz.

“I think Warhol would have embraced Chloe. She is the essence of Pop. I think they would have actually been good friends or great rivals.”

Statue of limited liberty

Nona Faustine is so passionate about revealing the full history behind public sites of historical importance that she posed naked and vulnerable at a number of them, bringing light to the invisible, erased, and forgotten.

Aimed at exposing New York City’s 201-year history in the slave trade, in 2013 Faustine took self-portraits wearing only white high heels against the backdrop of famous landmarks such as Wall Street and the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. The unflinching photos went viral, revealing buried truths of these attractions and their ties to the bondage of slaves who were often displayed without clothing on the auction block. While not included in Fantasy America, two images from the White Shoes series, including the Wall Street image titled From Her Body Came Their Greatest Wealth, were recently acquired by The Warhol’s sister museum, Carnegie Museum of Art.

“It was one of the toughest things I ever did in my life, but I knew I had to do it,” says Faustine about taking the images that garnered worldwide attention and were created alongside those in her My Country series. “It was an act of desperation, of sorrow, but also joy because I am a free woman, and my people were triumphant in the end. The nudity was something I felt absolutely necessary to be seen and heard and understood. When you see a naked woman in that vulnerable position, she is putting herself in danger.”

The descendant of slaves from North Carolina, Faustine grew up in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood. Her father, an amateur photographer, would bring home Time and Life magazines. And while she loved studying the works of famous photographers, she says she rarely saw photographs made by Black artists on those pages.

Nona Faustine, Fragment of Evidence, 2019, Courtesy of the artist and Two Palms © Nona Faustine

“This show is about life in America from the perspective of artists: the good, the bad, and the ugly.”

– José Carlos Diaz, Chief Curator at The Warhol

Just as Warhol captured Lady Liberty enveloped by scaffolding, Faustine presents in Fantasy America her own take on the monument and the limited freedom it represents. She happened to be on the Staten Island Ferry in 2016, right before the election of President Trump, and while passing Ellis Island she snapped a photo of the statue, the edge of a window frame leaving a symbolic black blur across the statue’s pedestal.

“It’s almost as if freedom, in that picture, was disappearing,” says Faustine. “Something made me push the shutter. I could have lifted the lens up or cropped it out, but I didn’t. I am always looking for those accidents, those magic moments in photography.”

Fantasy America is presented by Bank of America and generously supported by Artis; the Arts, Equity, & Education Fund; the Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation; The Fine Foundation; the Sheila Reicher Fine Foundation; Richard King Mellon Foundation; Joshua Hagen & Todd Kratofil; Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield and Allegheny Health Network.