Iconic photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris didn’t document just any community. Then one of the most vibrant and consequential communities of color in the United States, Pittsburgh’s Hill District and surrounding areas were his home, and the people he photographed were his neighbors. Among the most prolific photographers of the 20th century, Harris affectionately captured his neighborhood’s cultural, economic, and political life from the inside, telling the stories as only he could.

Over 40 years, he shot at least 80,000 images, many of them produced while on assignment for the Pittsburgh Courier, at the time the country’s widest-selling and most influential black newspaper. Today, the Teenie Harris Archive at Carnegie Museum of Art is considered one of the country’s most detailed and intimate photographic records of the black urban experience.

Installation view of In Sharp Focus: Charles “Teenie” Harris | Photo: Bryan Conley

In a Scaife Gallery newly dedicated to the archive, 36 black-and-white prints comprise a fresh take on Harris’ work. Titled In Sharp Focus: Charles “Teenie” Harris, the installation includes a mix of photojournalism, studio photography, and everyday snapshots, and highlights three critical aspects of the archive that connect the past and present: access and opportunity, complex identities, and social networks.

A few classic Harris images, such as the little boy boxer and Kay’s Valet Shoppe, make the cut. But most of the photographs are on public view for the first time. Extending the space’s impact in a big way is a searchable digital catalog of some 60,000 images that visitors can access using iPads in the gallery, which is designed to double as a place to host programming for and of the community.

A natural talent with no formal training, Harris photographed the likes of baseball great Jackie Robinson and jazz singer Lena Horne, but more often focused his lens on the everyday. From about 1935 to 1975, his photographs bore witness to baptisms, birthdays, weddings, anniversaries, and funerals—the full cycle of life. “You knew it was an event if Teenie was there,” says Charlene Foggie-Barnett, who grew up being photographed by the artist and has served as a liaison between the museum and Pittsburgh’s black community since 2006 and as an archive specialist since 2010.

Through the characters in his plays, “playwright August Wilson explained our lives,” says Foggie-Barnett. “Teenie did it without a single solitary word.”

Shifting Access and Opportunity

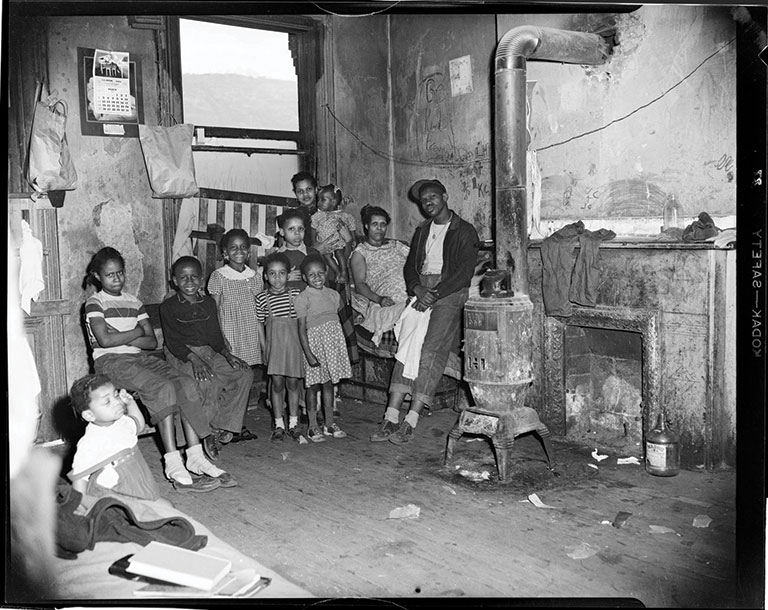

Inadequate housing and crumbling infrastructure have long plagued Pittsburgh’s black neighborhoods. Over four decades, Harris recorded a complex reality: the destructive effects of structural racism alongside against-the-odds achievement and a persistent demand for equality.

“I am both fascinated and disturbed by how the problems of the past come back to haunt us through the lens of his camera,” author and oral historian Yvonne McBride observed about Harris’ photographs in a 2015 essay. “Who could have imagined that 50 years later we would still need to argue the case for employment opportunities, business opportunities, and affordable housing for both new and lifelong residents—especially when that development takes place within our own communities?”

In seeming contrast to pictures of empowerment, there are also images of people living in substandard conditions. These images were used to document Courier stories that sought to expose substandard housing or absentee landlords. They, too, can be interpreted as a form of protest image.

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Lillie Copeland and her family posed in their dilapidated home with graffiti on wall inscribed “Be kind to everyone,” 2919 Penn Avenue, Strip District, March 1951

“I am both fascinated and disturbed by how the problems of the past come back to haunt us through the lens of his camera.”

– Oral historian Yvonne McBride

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Protesters outside of U.S. Steel building, including Byrd Brown with sign reading “NAACP PGH Branch,” and Judge Henry Smith with sign reading “US Steel still has segregated facilities in 1966,” Downtown, June 1966

No Single Idea of Blackness

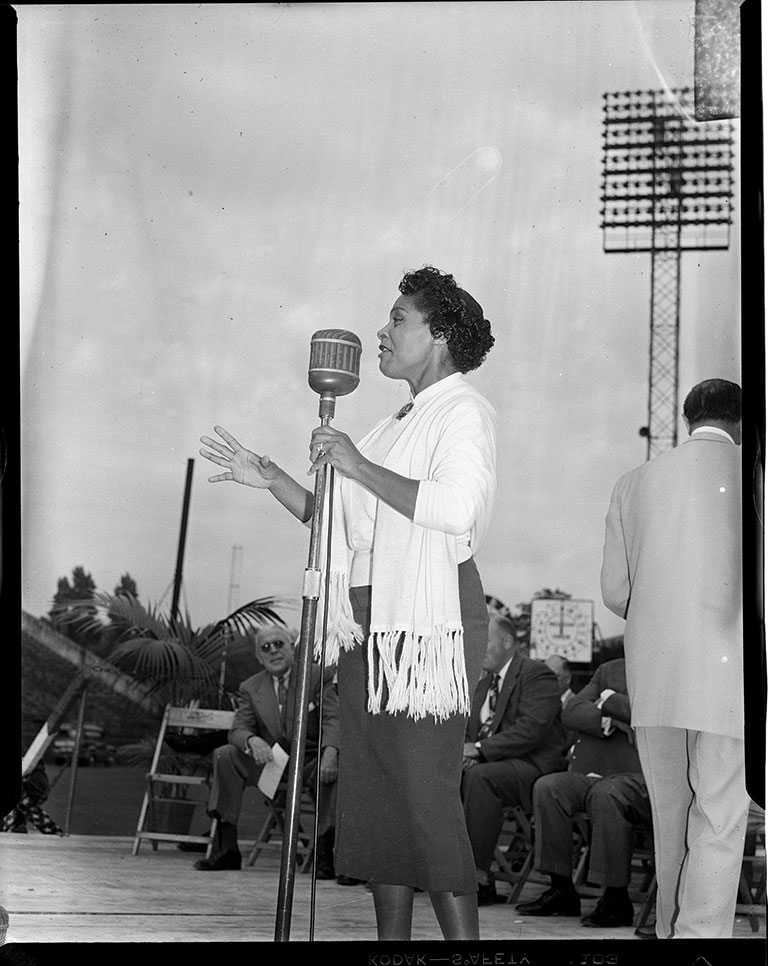

Harris had an extraordinary gift for capturing the complexity of black identity within a single frame, says Dominique Luster, the Teenie Harris Archivist. “Living in a world of institutional oppression means you can flourish as a black, female business owner, but still face discrimination,” she says. “It’s a very complicated story to tell in pictures.”

By dismissing any single idea of “blackness,” Luster notes, Harris documented the humanity in everyday moments of ordinary people, taking great care to contextualize his subjects, and revealing that most people live at the intersection of many identity categories—from race and ethnicity to age and socioeconomic status.

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Singer Velma Carey singing, with Pittsburgh Mayor David L. Lawrence seated in background, during “I am an American Day” celebration at Forbes Field, Oakland, September 1952

“It’s a very complicated story to tell in pictures.”

– Dominique Luster, Teenie Harris Archivist

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Woman in profile modeling hairstyle, c. 1930–1950

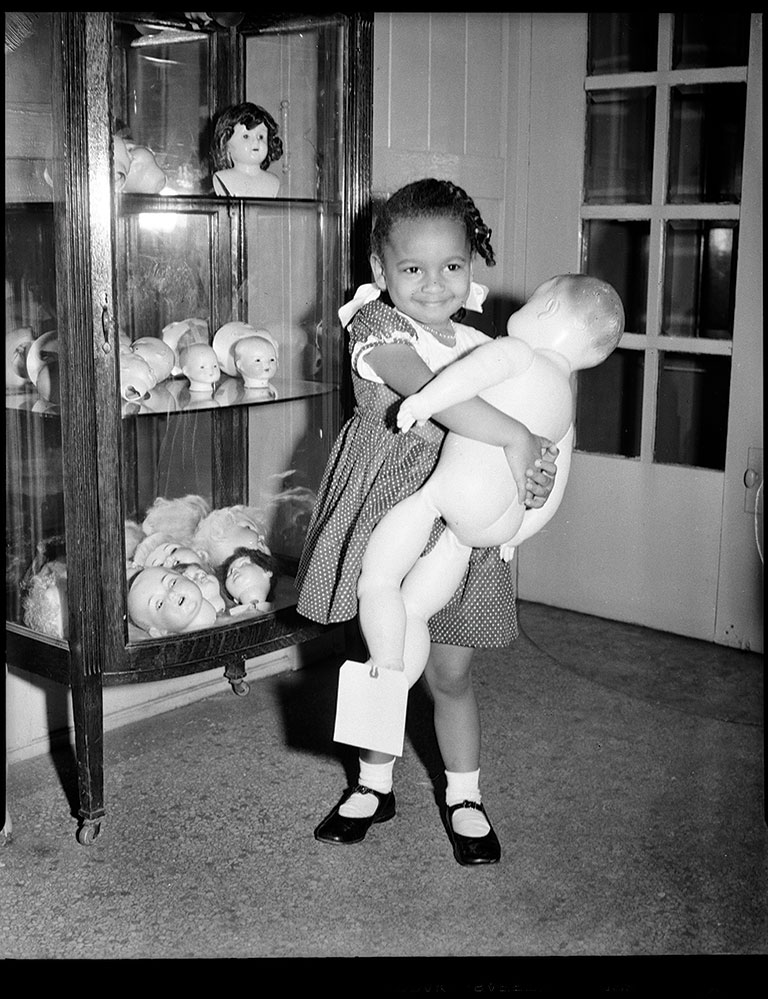

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Girl holding doll, possibly in Stevenson Doll Shop, c. 1950–1960

Social Networks

Photographs in black newspapers offered readers positive images of themselves and their communities—a reflection they seldom found elsewhere. Harris and photojournalists like Vera Jackson of south Los Angeles avoided sensationalism, whether documenting a crime scene or a glamorous social event.

In a somber Harris image showing family members of a murder victim embracing outside the victim’s apartment, Foggie-Barnett says she feels as if she’s standing inside the photograph, flooded by sorrow. “The community trusted Teenie; that’s how he got access during moments like these, and he puts us there. We don’t see the emotion, we feel it.”

“The community trusted Teenie; that’s how he got access during moments like these, and he puts us there. We don’t see the emotion, we feel it.” – Charlene Foggie-Barnett, archive specialist

The social networks section of the installation underscores the importance of alliance building in African American culture in the 20th century. Many formal social groups were initially formed in response to white social groups denying entry to blacks. Many of them endure, including the more than 100-year-old social club known as FROGS, an acronym for Friendly Rivalry Often Generates Success, a hub for male, middle-class professionals once known for throwing the social events of the year. As Harris’ images show so powerfully, informal networks were just as vital. In one especially tender interaction, he captures two young girls who are all smiles as they visit with a community elder named Sabre “Mother” Washington, a former slave. “We can only imagine what they might be talking about,” says Luster, “but what a precious moment.”

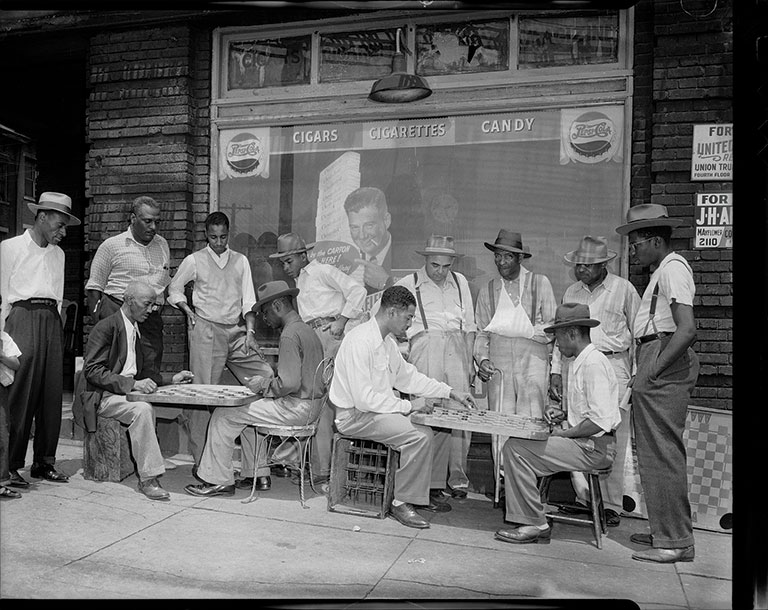

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Checkers players, including Albert Valentine, John Gray, Clarence Walker, Ray Harris, Joe Mitchell, R. L. Lipscomb, Richard Reed, West Wall, Ted Campbell, Claud Foster, Clifford L. Brown Jr., and “Checkers” Brown, in front of Babe’s Place, Logan and Epiphany Streets, Hill District, June 1949

Charles “Teenie” Harris, Roberta Thomas and Joyce L. Addaway (Harris) with former slave Sabre “Mother” Washington, in her home at 8141 Conemaugh Street, Homewood, c. 1949