Candy Darling knew how to channel her inner bombshell. The late transgender icon strutted on stage in glittering gowns and lush blonde wigs, a look she cultivated by studying her idol, Kim Novak.

“I’ve had small parts in big pictures and big parts in small pictures,” she said of her acting career in the late 1960s and early ’70s. Working alongside Tennessee Williams in one of his original plays, Small Craft Warnings, Darling played the glamorous, sexually promiscuous Violet. She also had a knack for gritty roles in underground theater productions and the profanity-and nudity-filled films of Andy Warhol.

That Warhol and Darling became close friends seemed like destiny in the era of gender-bending, glam rock music, and the decadent New York high-low art scene. “Candy really embodied this kind of uptown-downtown vibe. She was glamorous, but she was also leading this punk rock lifestyle,” says Ben Harrison, curator of performing arts and special projects at The Andy Warhol Museum. “Andy loved big personalities, and Candy was larger than life.”

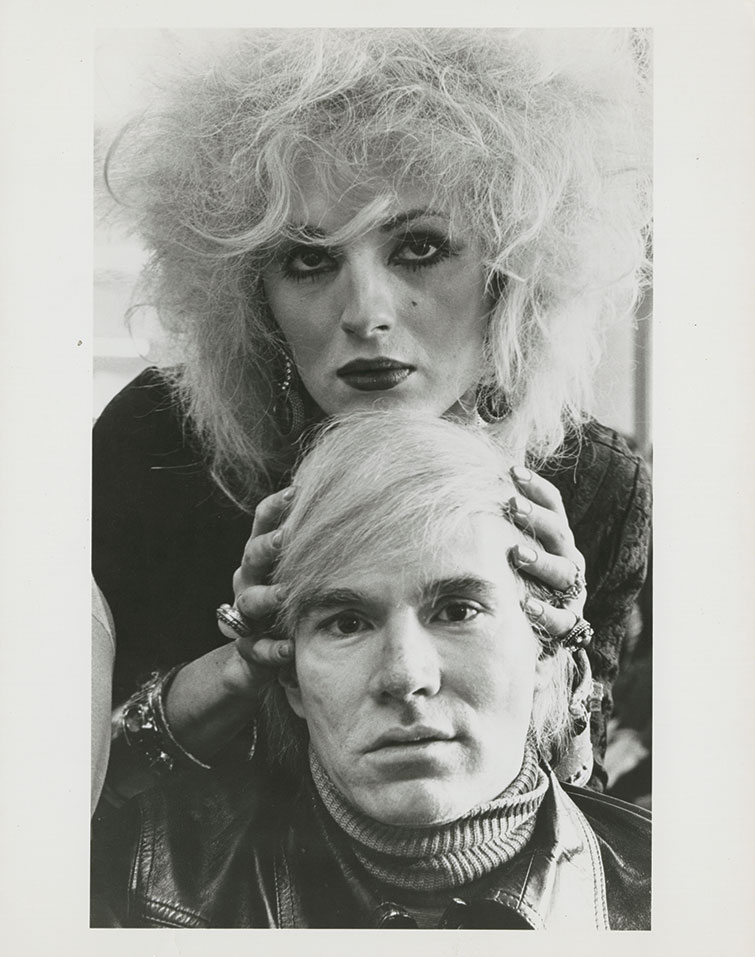

Cecil Beaton, Andy Warhol and Candy Darling, New York, 1969 © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

Museumgoers can catch a glimpse of her sultry fashion sense on two blonde mannequins dressed in Darling’s authentic evening gowns, both plucked from the vast Warhol Archives numbering more than a half-million objects.

Darling is among a group of groundbreaking figures with deep Warholian ties who will be featured in a new museum-wide exhibition dubbed Femme Touch, on view April 24–September 6. A collaboration between curators, educators, and archivists, the show will shine a light on nine fascinating women and femmes in Warhol’s inner circle. Collaborators, confidantes, and muses, they helped advance and shape the Pop artist’s career. Overshadowed by the force field that was Warhol, they’re often left out in the retelling of Warhol’s story, some say even by Warhol himself, their accomplishments having faded with time.

“We expect this will introduce audiences to individuals they don’t know, who are both captivating and pioneering,” says José Diaz, chief curator of The Warhol and lead organizer of Femme Touch.

Featured are Candy Darling and the artist’s longtime collaborator Brigid Berlin, as well as models and actresses Jane Forth and Donna Jordan, who changed the definition of beauty in the freewheeling ’70s. The presentation puts Warhol’s work in dialogue with artifacts from the lives of these influential innovators, as well as with those of his fellow stars of underground cinema: actress and singer Tally Brown, influential filmmaker Barbara Rubin, and award-winning drag performer Mario Montez. It also reexamines the story of writer Valerie Solanas—Warhol’s would-be assassin—and his beloved mother, Julia Warhola.

“Women were very important in Warhol’s life, starting with his mother, Julia. He worked in a very feminine universe, first as a commercial illustrator for the fashion industry and later as court painter to the rich and famous.” – Jose Diaz, chief curator of The Warhol

All but Solanas, Warhola, and Rubin are known as Warhol “Superstars,” a unique clique of characters who inspired the artist and whose thirst for individuality and fame rivaled his own.

Perhaps the most famous of the Superstars, socialite Edie Sedgwick, became the ’60s “it girl” only partly through her relationship with Warhol. Because her story is so well known, she’s not a central focus of Femme Touch.

But Sedgwick and other usual suspects such as Velvet Underground icon Nico and actress Susan Bottomly, known as International Velvet, do make significant appearances in rarely exhibited, color Warhol films screened on the museum’s second floor. It’s there where visitors can also surround themselves with an impressive number and variety of Warhol’s famous silkscreened portraits of women and femmes. Among those featured: Jackie Kennedy, Grace Jones, Debbie Harry, Judy Garland, and Wilhelmina Ross, who in 2019 was identified as one of Warhol’s sitters for his commissioned Ladies and Gentlemen series featuring anonymous drag queens and transgender women of color.

Warhol the experimental filmmaker often provided little instruction to the talent; instead, he would set up the camera, turn it on, and encourage his stars to act largely like themselves. Through this process, he invented his own idea of the Superstar, characterized by the motley crew of actresses, models, drag queens, socialites, and artists he hung around with at his New York studio, the Silver Factory.

Femme Touch takes the lesser-known, larger-than-life figures out of the shadows, all the while adding rich context to the world in which Warhol lived.

“Women were very important in Warhol’s life, starting with his mother, Julia,” Diaz says. “He worked in a very feminine universe, first as a commercial illustrator for the fashion industry and later as court painter to the rich and famous. Many in his inner circle were gifted artists in their own right, and they inspired him.”

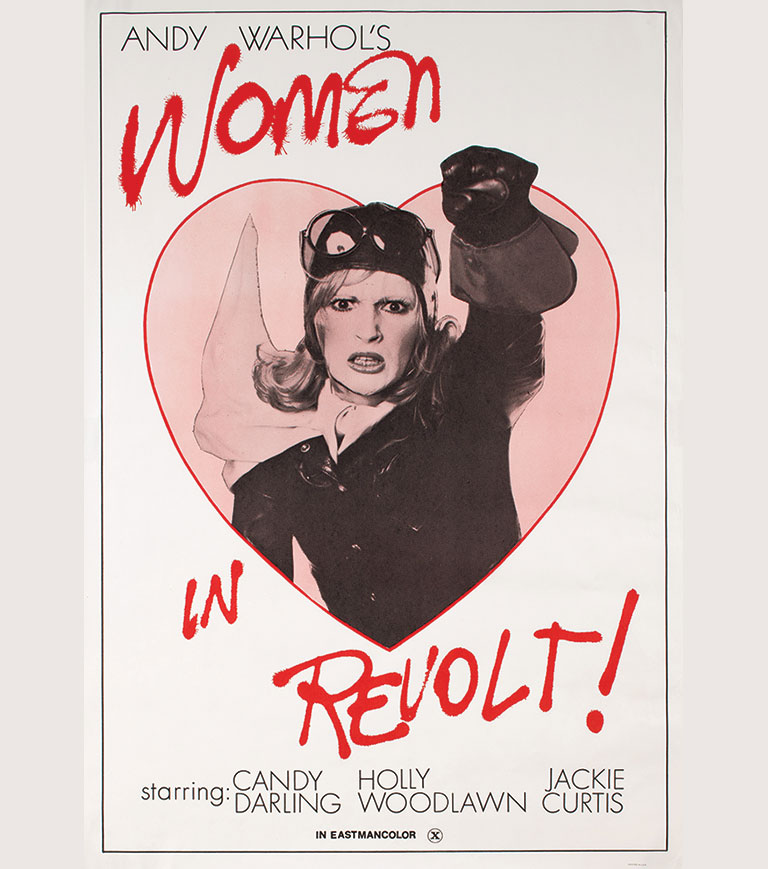

Film Poster (Women in Revolt), 1971, The Andy Warhol Museum; Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Pushing Boundaries

Decades before Laverne Cox and Caitlyn Jenner graced magazine covers, there was Candy Darling. Artifacts of her short but dazzling life are on display on the museum’s fifth floor. Darling became a transgender trailblazer who starred in Warhol’s movies Flesh (1968) and Women in Revolt (1971). She counted as her friends A-list celebrities such as Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dennis Hopper. Director John Waters, another friend, once said of her star power, “Candy fit in perfectly because she was like a real movie star from MGM, only in a world that was filled with LSD and speed.”

In one film clip, Darling recites lines from Kim Novak movies to a young and astonished Dennis Hopper. “It’s almost as though she is auditioning for him, and he seems so enamored with her,” Harrison says.

Darling’s early death—she died of lymphoma in 1974 at age 29—prevented her from ever achieving the mainstream stardom she dreamed of.

Peter Beard, Donna Jordan and Jane Forth, ca. 1970 © 2019 Peter Beard/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fellow Superstars Jane Forth and Donna Jordan were discovered by fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez in Central Park. “Antonio’s Girls,” a group of beauties that also includes Jessica Lange and Jerry Hall, changed the idea of the runway model with their unconventional style and bold personalities.

Inspired by the ’20s, Forth had an art deco look, her hair slicked with Wesson cooking oil and her eyebrows plucked to tiny apostrophes. Jordan, nicknamed Disco Marilyn, exuded ’70s glamour. A fourth-floor installation will show Forth and Jordan starring in Warhol’s film L’Amour, a comedy about American beauties showing up in Paris and becoming gold-digging supermodels. Never before shown glamour shots, borrowed from the archives of Antonio Lopez and Chris von Wangenheim, will be displayed, as well as photos of the models in Warhol’s Interview magazine.

As Diaz notes, “They pushed the extremes of gender through hyper-femininity but also androgyny.”

Androgynous style was also evident in the 1971 Warhol play, Pork, which is brought to life in the exhibition through photographs and snippets of its experimental dialogue. A satiric and bawdy look at life at the Silver Factory, Warhol adapted Pork from taped conversations, and its influence on popular culture was lasting. Turns out David Bowie went to see Pork in August of that year, during its run in London. “The wild exhibitionistic cast, the androgyny, and the gender play of Pork seem to have been an influence and inspiration reflected in the aesthetic of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars album released almost a year later in June 1972,” Harrison says. Ziggy Stardust became an androgynous bisexual, and Bowie’s manager Tony Defries hired a few of the cast and crew members from Pork to work for his production company, MainMan, in New York. Songs by David Bowie, Lou Reed, and other glam rock musicians help set the scene in this gallery.

Though Pork inspired Bowie, it annoyed critics. Newspaper clippings with scathing reviews are mounted on a gallery wall. “It’s very tongue-in-cheek. A lot of the cast was nude and it was pretty profane,” Harrison says. “The dialogue was mostly non-linear and absurdist.” Museumgoers pick up a rotary phone to listen to two local actors, Lissa Brennan and Brian Siewiorek, reading the lines from the groundbreaking stage production, specifically recorded for the installation.

The script was partially based on transcripts of tape-recorded conversations between Brigid Berlin and Warhol, and conversations between Berlin and her mother, Honey Berlin.

Brigid Berlin, Self-Portrait, ca. 1969, The Andy Warhol Museum; Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

The daughter of Richard Berlin, chairman of Hearst Media, Brigid Berlin was born in 1939 into great wealth and was groomed to be a socialite. She was a self-proclaimed “overweight troublemaker,” says Danielle Linzer, director of learning and public engagement at The Warhol. “As a girl, her mom would give her diet pills and give her cash for every pound she lost.”

Instead of hobnobbing with Manhattan’s upper crust, Berlin rebelled by living a bohemian lifestyle. When she visited the Silver Factory in 1964, she knew she had found her tribe. While other women cycled in and out of Warhol’s orbit, sometimes upset that he didn’t pay them to be in movies or he had moved on to the next star, Berlin was a bosom friend and sounding board to Warhol until his death in 1987.

Berlin was a brash exhibitionist and naturally provocative performer, frequently appearing topless and making “tit prints” by using her bare breasts to imprint paint onto canvas. She was nicknamed Brigid Polk because of her habit of giving her friends at the Silver Factory “pokes,” injections of vitamin B and amphetamines.

For all her antics, she was a prolific artist. The Polaroid portraits she made of herself, Warhol, and other Silver Factory dwellers—some of them superimposed in front of Warhol’s own artworks—are included in the exhibition. Berlin, who still lives in New York, appeared in an impressive number of Warhol films, including Chelsea Girls. Like Warhol, she compulsively taped conversations, and was known for her signature double-exposed Polaroids.

When Berlin had gallstones removed, she wrapped them up in a box and gave them to Warhol with a note that read, “Now you have three of my most precious stones from my gallbladder. Friday, February 19, 1982. Much love, Brigid.”

A Life-Changing Encounter

The fifth-floor also contains sentimental notes Berlin wrote to Warhol while he was convalescing in the hospital after he was shot and nearly killed on June 3, 1968, by Valerie Solanas.

From the movie I Shot Andy Warhol to an episode of American Horror Story, Solanas looms large in pop culture. But her story goes beyond the “party line of a crazy ‘feminist’ who shot Warhol for fame,” says Nicole Dezelon, associate director of learning at The Warhol.

Instead of the stereotypical trope, the exhibition tells the deeper tale of Solanas’ unhappy life, filled with abuse, trauma, and undiagnosed mental illness. We learn that she ran away from home at age 15 after claiming sexual and physical abuse from both her father and grandfather. “She fell into this relationship with a married man and ended up having a child that she had to give up for adoption,” Dezelon says. “She had a very rough start.” She turned to panhandling and prostitution to support herself.

Despite early trauma, Solanas earned a degree in psychology at the University of Maryland and took a few courses at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1967, she wrote the Society for Cutting Up Men (SCUM) Manifesto, arguing that men had ruined the world, with a call to take back everything men destroyed. “She has been characterized as a radical feminist writer but she never called herself a feminist,” Dezelon notes.

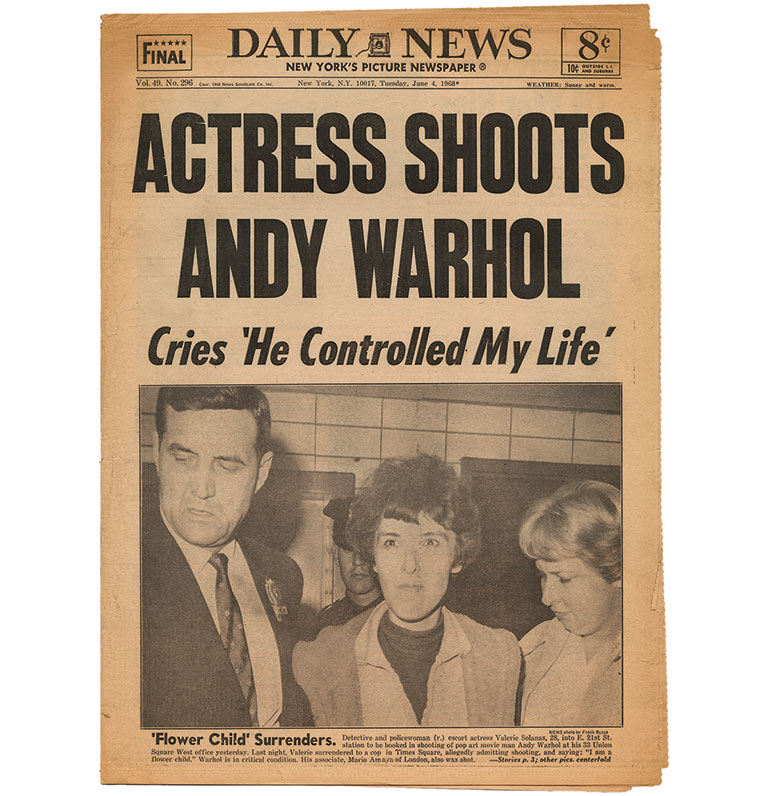

Newspaper section (Daily News – Vol. 49, no. 296, June 4, 1968), The Andy Warhol Museum; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Solanas also wrote the play titled Up Your Ass, and she gave her only copy to Warhol. She had interactions with the artist but was more of a hanger-on than a member of his avant-garde world. Warhol told her she was a wonderful typist and that she should come work for him at the Silver Factory—a comment that likely set her off, Dezelon says. Warhol seemingly forgot about her play and misplaced it, but in Solanas’ paranoid mind, Warhol was stealing her work.

The exhibition will include news footage from the day of the shooting showing the bullet holes found in the Silver Factory window and the Daily News headline—“Actress Shoots Andy Warhol. Cries ‘He Controlled My Life,’”—her words when she turned herself in to police. On display are photos of Warhol’s scars and one of the extra-small corsets he was forced to wear after Solanas shot him in the abdomen. He wore the undergarments, many of which Berlin hand-dyed a variety of colors, to help support his organs. The shooting was such a traumatic event that he closed the Factory’s doors to outsiders and became what friend and photographer Billy Name coined “Cardboard Andy,” so sensitized that he couldn’t be touched without jumping from fear.

“There is one camp who thinks he exploited women and another camp thinks he helped many women’s careers. Like everything else with Warhol, it’s a matter of opinion.” – Nicole Dezelon, associate director of learning at The Warhol

The stories in the exhibition highlight two conflicting theories of Warhol’s relationships to the uniquely talented women and femmes who hung around the Silver Factory. “There is one camp who thinks he exploited women and another camp thinks he helped many women’s careers,” Dezelon says. “Like everything else with Warhol, it’s a matter of opinion.”

Diaz says Warhol had complicated relationships with his Superstars and other women in his orbit, but the most ambitious ones saw Warhol as a stepping stone to their own brilliant careers. “We are not trying to credit Warhol,” he says. “We are crediting these fascinating women who deserve to have their stories told.” n

Femme Touch is presented by Bank of America and Steven Alan Bennett and Dr. Elaine Melotti Schmidt, Founders of The Bennett Collection of Women Realists.