The walk may have been short, but the journey was long.

For the past two years, Akemi May, Carnegie Museum of Art’s associate curator of works on paper, has been busy scouring the museum’s collection database in search of Japanese prints. Her goal was to create a comprehensive exhibition that would span more than a century of changing techniques, subject matter, and philosophies.

As part of her discovery process, May would often leave the confines of her office and set out to explore the museum’s in-house print storage room. The short trek from her desk became a rite of passage, an almost daily affirmation—each step asserting that her destination was drawing ever nearer.

Because, as May readily acknowledges, a computer screen is no substitute for the real thing, especially when dealing with woodblock prints. By their very definition, prints are produced in multiples, each iteration of a common design quietly asserting its individuality.

Hashiguchi Goyō, Woman in a Summer Kimono (Natsui no onna), 1920, Carnegie Museum of Art: Bequest of Dr. James B. Austin

“It’s easy to think that all prints are the same, but they’re not,” May says. “Every single impression has its own subtle variations—registration areas that are slightly off or places where the ink was applied differently.

“These are the details you can only detect when you look at it in person.”

The print room itself is purely functional, and it includes the 2,600 objects that comprise the permanent collection of Japanese prints—the most expansive grouping within the museum’s works-on-paper holdings. Neatly secured in rectangular black boxes of various dimensions and proportions, they are kept safe from the damaging effects of light.

“It’s easy to think that all prints are the same, but they’re not. Every single impression has its own subtle variations—registration areas that are slightly off or places where the ink was applied differently.”

–Akemi May, associate curator of works on paper at Carnegie Museum of Art

Matsubara Naoko, Shôjô (Nô Dancer), 1977, Carnegie Museum of Art, Gift of Drawing and Print Club, the Detroit Institute of Arts, © 2009 Naoko Matsubara

Working from her preliminary list, May would seek out the prints she wanted to examine more closely. Then: click, click. She would unfasten the latches and lift up the lid, opening it like a book revealing its secrets.

“Once you physically start going through the boxes, you are reminded of the actual sizes of the prints, you see the different techniques and different approaches,” May says. “It’s truly a special experience.”

That experience culminated in Imprinting in Their Time: Japanese Printmakers, 1912–2022. Making its debut in June, the exhibition will call Scaife Gallery One home through May 12, 2024. This nearly yearlong run allows museumgoers to enjoy two additional rotations of prints—one opening in October 2023, the other in February 2024. As a result, some 270 different works—many of which rarely see the light of day—will grace the gallery. The space will also feature several cases displaying print portfolios and bound material, including books and magazines.

Although it’s been more than 15 years since the museum’s last foray into this subject matter (2007’s Modern Japanese Prints: 1868–1989), what makes this current exhibition even more remarkable is its longevity.

“This will be the first time we’re offering visitors this prolonged experience,” May says. “Because the prints are very light-sensitive, we can’t keep them on view for longer than three months. The changing rotations allow us to refresh the show and share multiple works from a single artist throughout the different installations.”

The ‘New’ Era

The exhibition does not adhere to a strict timeline. Rather, it disrupts the chronology by taking a “thematic approach,” May says, guiding museumgoers through notable artistic movements that have come to define the Japanese time-honored tradition of printmaking.

The themes revolve around the shin-hanga movement (“new prints”), which dates back to 1915; the sōsaku-hanga movement (“creative prints”), which began in 1904; and contemporary prints, which are ongoing. Their stories diverge and intertwine just as the museum’s own holdings are highlighted and complemented with works on loan from regional private collections.

“I’ve been wanting to connect with local lenders while also bringing the story of our collection forward for some time,” May says. “Now we have an opportunity to feature this work in a very in-depth way.”

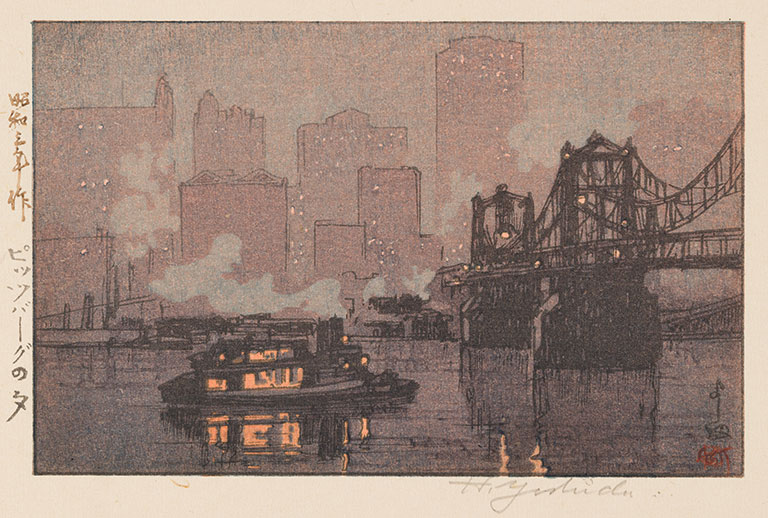

Among those prominently featured is Yoshida Hiroshi’s Evening in Pittsburgh (Pittsubaagu no yû), 1928. Presenting an enigmatic view of the city—complete with a twinkling skyline glistening off the Allegheny River—the print is relatively small (postcard-size) but nonetheless evocative.

Yoshida Hiroshi, Evening in Pittsburgh (Pittsubaagu no yû), 1928, Carnegie Museum of Art, Bequest of Dr. James B. Austin

“It has a real presence,” May says, “and it promises to be one of the most popular pieces in the show.” It will also be the only print to remain throughout the entirety of the exhibition. (Actually, each installment will feature a subtly different version: one from the museum’s collection, the other two shared by local collectors.)

Yoshida is closely associated with the shin-hanga movement that thrived in Japan during the early 20th century. Literally meaning “new prints,” shin-hanga represented a mashup of traditional themes in printmaking—like landscapes, birds and flowers, beauties (or beautiful women), and famous actors—with Western-influenced aesthetics that emphasized a heightened sense of realism.

Although shin-hanga offered a fresh perspective to the traditional Japanese graphic art form, the business of printmaking (hanmoto) remained virtually unchanged. Publishers ruled the medium: They hired the artists to create the designs, employed carvers to chisel the images into the woodblocks, and then had their printers ink the blocks and transfer the scene onto paper. It was a collaborative process that required the skills of a series of highly trained professionals to complete a single print.

The emergence of shin-hanga is credited to Watanabe Shōzaburō, an influential print publisher who was looking to revitalize a stagnant industry. Prior to 1915, Watanabe’s contemporaries were content to churn out reproductions of classic prints (ukiyo-e). He was looking for more opportunities to showcase new, younger artists and engage a broader international audience.

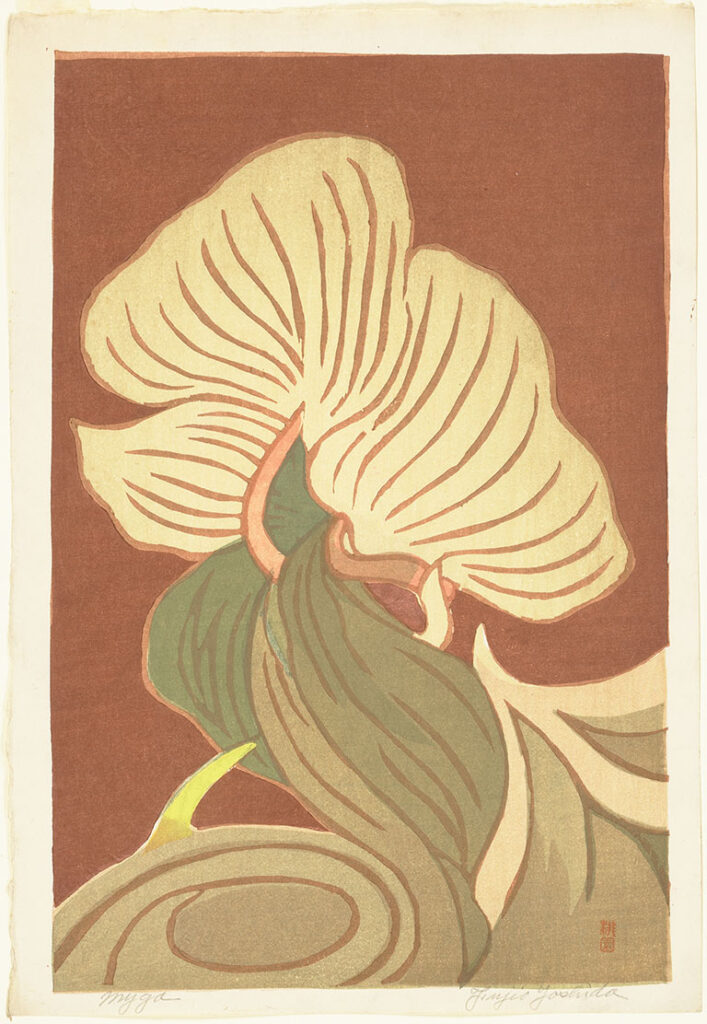

Yoshida Fujio, Myga, 1954, Carnegie Museum of Art, Carnegie Museum of Art, Bequest of Dr. James B. Austin, © Yoshida Fujio

He succeeded. By the ’30s, Watanabe was successfully marketing this modern view of old-world Japan to Western outlets via museum and gallery showings. Americans, in particular, became infatuated with shin-hanga prints. Sadly, much of Watanabe’s early inventory of prints and their original printing blocks were destroyed in a fire following the 1923 Great Kantō Earthquake. He managed to recreate, with some changes and modifications, many of the originals.

But there was another reason shin-hanga prospered, at least until the late 1950s; it was the antithesis of the sōsaku-hanga movement.

The Pendulum Swings (Again)

As the 20th century was dawning, Japanese artists began asserting their creative autonomy by rejecting the traditional collaborative model of printmaking in favor of a more self-centered approach.

At the core of sōsaku-hanga, aka “creative print,” was the artist as designer, carver, and printer. The finished pieces were truly a reflection of a singular vision. This notion of self-determination can definitely be linked to the European avant-garde movement that saw art expanding into the realms of abstraction and experimentation, and the artists wielding political, cultural, and even mystical power.

“Some of the artists in the exhibition have an almost spiritual way of looking at the art they’re creating that both reflects and respects the medium,” May says. “For example, Munakata Shikō talks about how he’s there to release the design from the block. That’s really a beautiful and fascinating approach or philosophy.”

Still, the finished products could look and feel less finished.

“In shin-hanga, the artists relied on skilled carvers—and, in fact, many artists used the same carvers,” May says. “In the sōsaku-hanga prints, you can see that there are varying degrees of refinement in the carving. It makes them more interesting and individual.”

And that was precisely the point.

“Some of the artists in the exhibition have an almost spiritual way of looking at the art they’re creating that both reflects and respects the medium.”

–Akemi May

Sōsaku-hanga’s impact continues to resonate to this day, in no small part because many of the young, aspiring artists of the movement grew to become the mentors and teachers of the next generation.

The exhibition calls out two artists in particular—Onchi Kōshirō and Hiratsuka Un’ichi—and links them both visually and conceptually to the work of the artists who followed them. This enables visitors, as May puts it, “to see the trickling of influence that leads to the modern era.”

That trickle turned into a deluge. Contemporary Japanese printmakers are not content with the traditional confines of their craft. They’re incorporating different surfaces and textures into the form, not to mention using found or appropriated objects. Sometimes they don’t even apply ink.

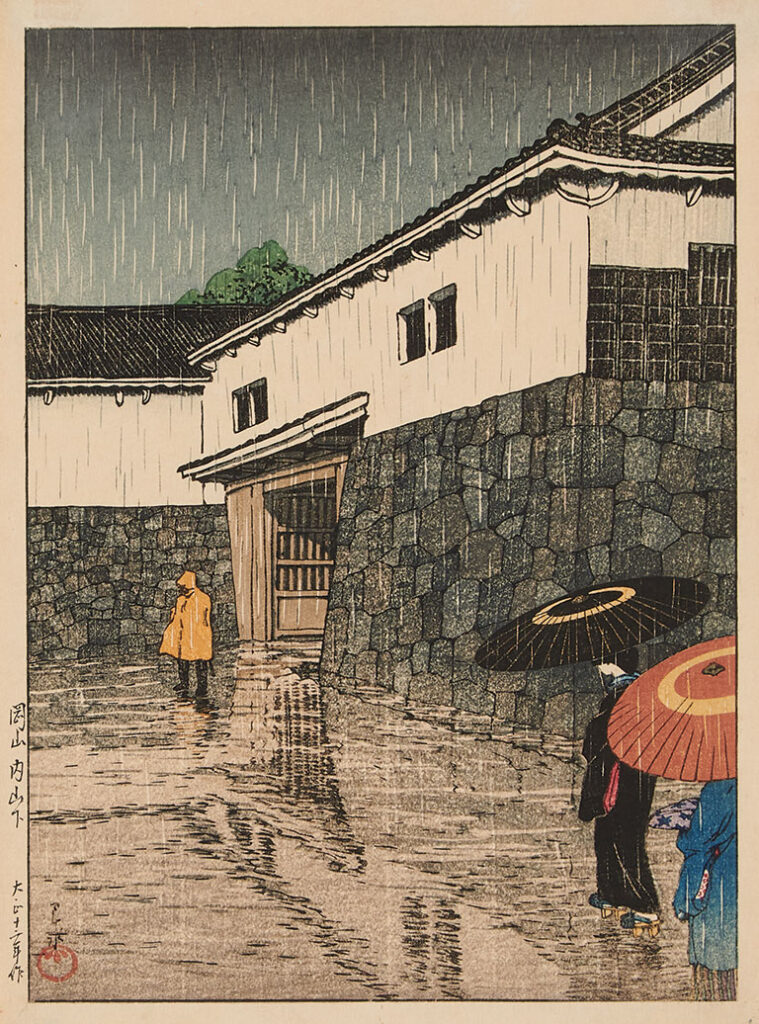

Kawase Hasui, Watanabe Shōzaburō, publisher, Uchiyamashita, Okayama, 1923, Collection of Dr. Lila Penchansky

The results continue to inspire private collectors like Lila Penchansky. A Pittsburgh pathologist, Penchansky did not set out to fill her house with Japanese prints. “I was looking to buy a gift for someone and stopped in this little store,” she recalls. “They had a whole stack of prints, and I couldn’t make up my mind so I decided to buy one for the present and one for me.”

Penchansky admits that she didn’t know what she was buying; she just knew she liked the bold combination of patterns and the “strong” use of colors.

Now, nearly 35 years and 400 prints later, she still doesn’t consider herself an art connoisseur. “The opinions of others don’t matter,” Penchansky says.

Despite her indifference to what other people might think, many pieces from her collection are highly regarded. In fact, May lobbied Penchansky to loan a few standouts to supplement the exhibition’s contemporary section.

Kurosaki Akira, Red Darkness 1 (Les Ténèbres Vermillon/Akai yami 1), 1970, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh: Collection of Dr. Lila Penchansky, © Estate of Akira Kurosaki

Walking through the gallery, May points to two distinctly different works from the Penchansky collection that speak to the collector’s ever-evolving artistic sensibilities. First, there’s Kurosaki Akira’s 1970 Red Darkness 1 (Les Ténèbres Vermillon 1/Akai yami 1), which has a bold red, midcentury, science fiction vibe to it. Then there’s Hamanishi Katsunori’s 2020 Manzyusyage (Flowers of Heaven), a tranquil meditation on the red and white spider lilies common to Japan.

Penchansky is happy to know that museumgoers may come to appreciate contemporary Japanese prints in general, and certain artists in particular. Perhaps visitors will share her same emotional connection with the art.

“For me,” Penshansky says, “this is something very personal that now I’m sharing with other people.”

Generous support for the exhibition has been provided by the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation. Additional support has been provided by the Bernard S. and Barbara F. Mars Fund.

Carnegie Museum of Art’s exhibition program is supported by the Carnegie Museum of Art Exhibition Fund and The Fellows of Carnegie Museum of Art.

Carnegie Museum of Art is supported by The Heinz Endowments and Allegheny Regional Asset District. Carnegie Museum of Art receives state arts funding support through a grant from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, a state agency funded by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.