|

|||||||||||

| Carnegie Science Center jumps into Pittsburgh’s burgeoning maker community by giving new digital creators of all ages a space to experiment.

Inside Carnegie Science Center’s new do-it-yourself Fab Lab (short for digital fabrication laboratory), Steve Weiss tries his hand at Inkscape, a free and open-source graphics software. The challenge: design and build a basic parallel electrical circuit. Streetlights, for example, are powered by this kind of device so that, unlike on a string of holiday lights, if one light goes out the others don’t follow. So what’s new about this triedand- true middle school science lesson, especially for a seasoned science teacher like Weiss? Digital making.

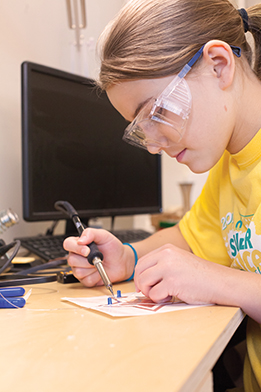

By forgoing the traditional, prepackaged kit used for decades to teach this basic electronics lesson, personalization and experimentation—in addition to the science— are king in the Fab Lab. Case in point (albeit on a beginner’s scale): The colleague to Weiss’ right uses Inkscape to draw a conductor in the shape of a star, the colleague to his left models a butterfly. At their instructor’s urging, Weiss confirms that his pattern is sized correctly and then transfers it by flash drive to a desktop vinyl cutter. Within minutes,Weiss’ creation prints letter by letter on adhesive-backed copper foil, declaring: “Science Rules.” A 3-volt battery pack in hand, Weiss’ plan is to literally and figuratively shine a light on science. “This,” he says, motioning to the unassuming lab brimming with tools of the modern maker movement— 3D printers and scanners, laser printers, and a pair of computer-controlled milling machines, all connected through open-source software—“will hook some of my kids who don’t see themselves as scientists. “A lot of my kids are very hands-on, it’s the only way they learn,” continues Weiss, who teaches grades five through eight at Pittsburgh Public School’s Sunnyside Elementary in Stanton Heights. “I need to meet them where they are because they’re not meeting me where I am.” Bridging that distance is part of what brings Weiss and a half dozen other regional educators to the Science Center on this warm June afternoon to brainstorm, experiment, collaborate, design, and build as part of a week-long “Fab Lab Boot Camp” for teachers —a full two months before the space is officially open for making. The ambitious end goal is to reimagine the classroom as a place where students are real-time inventors, scientists, and mathematicians who are given the freedom to experiment, fail, learn from their mistakes, and try again. A city of makers

“With the addition of Fab Lab at the Science Center, we can now put 1- to-99-year-olds in the making pipeline in Pittsburgh,” he says. “We’re part of the national conversation.” A conversation that President Obama amplified in this way: “Today’s D.I.Y. is tomorrow’s ‘Made in America.’ Your projects are examples of a revolution that’s taking place in American manufacturing— a revolution that can help us create new jobs and industries for decades to come.” A snapshot of Pittsburgh’s growing maker pipeline includes the MAKESHOP at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh, an ambitious mix of low- and high-tech tinkering designed largely for a younger audience; TechShop in East Liberty, designed for the digital maker-to-market audience; and thanks to the generous support of Chevron, the Science Center’s Fab Lab will fill a niche all its own— the digital “zero-to-maker” audience of all ages, with a focus on school kids and their teachers. Not satisfied to just bring eager makers to its new on-site Fab Lab, the Science Center is unveiling a 30-foot-long Mobile Fab Lab in September that its educators will roll into school parking lots for a week at a time. “The Science Center was a leader in the maker movement before it was called the maker movement. They’ve long encouraged visitors to explore with robots and build with giant blue blocks. The Fab Lab is the next evolution of that.”

- JUSTIN AGLIO, DIRECTOR OF INNOVATION FOR MONTOUR SCHOOL DISTRICTMaking, of course, is in Pittsburgh’s DNA. In the 19th century, Pittsburghers engineered an industrial economy, notable for its glass, iron, aluminum, and, as everyone knows, big steel. But over the last few years a new community of makers has flourished in the city—from kids hammering away in community libraries to successful robotic upstarts. Already a leader in hands-on science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) learning, the Science Center is jumping in to make digital making accessible to everyone. “The Science Center was a leader in the maker movement before it was called the maker movement,” says Aglio. “They’ve long encouraged visitors to explore with robots and build with giant blue blocks. The Fab Lab is the next evolution of that.” Failing betterLocated on the ground floor of Highmark SportsWorks®, Fab Lab is designed as a workshop— unpolished, unassuming, and functional. Its furniture was built in-house, serving as first-hand examples of how things are made. The premise behind the “anyone can make anything” approach is an open-access, shared learning environment “that embraces the idea of failing better,” says founder Neil Gershenfeld, the director of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms, where Fab Labs were born. When he started with 26 Fab Labs in 2002, Gershenfeld said, matter-of-factly: “Basically, the goal is to create a Star Trekstyle replicator in 20 years.” Since then, his global network spans more than 450 Fab Labs in 55 countries, including maker spaces in Detroit, Jalalabad, Afghanistan, Barcelona, Nairobi, and many points in between, including 95 in the United States. “It’s a huge advantage for makers in Pittsburgh to be looped into such a far-reaching community of doers,” says Liz Whitewolf, the education and technical manager of Carnegie Science Center’s Fab Lab. “We can get live video feed from other sites; it’s an amazing opportunity to partner on projects with Fab Labs around the world and learn from each other.” In the words of Gershenfeld, “The power of digital fabrication is social, not technical.” Part of the Fab Lab magic, says cultural literacy teacher Michelle King, is that it’s a place where everyone is a teacher and everyone is a student. This hones all-important “soft skills,” also known as 21st-century skills, including collaborating, problem solving, and being nimble in solution choices, notes King, who teaches at Pittsburgh Public’s Environmental Charter School, is a member of the Fab Lab advisory committee, and self identifies as a “learning instigator.” It also places real-world constraints on time, space, and material, invaluable lessons in an interconnected world. “The lab is a powerful incubator for ideas because it’s based on experimentation,” King says. “But our school systems are about getting it right the first time. Making is about trying something and getting things wrong. We have to look at how the two can influence each other.” The wow factorMuch like dinosaurs are for kids and science, 3D printers are a popular gateway to digital making. Also like dinosaurs, there’s no denying their wow factor. From 3D-printed skin and organs to prosthetic legs for a dog, the potential of 3D printers is nothing short of jaw-dropping. High-end versions print in plastics, but also in silver, gold, and other metals, along with ceramics, wax, and even food. The Andy Warhol Museum is providing 3D-printed and laser-routed reproductions of iconic Warhol paintings, including Marilyn, for visitors with visual impairments. The touchables have raised surfaces that accentuate the lines, shapes, and contours of the worldfamous artwork.

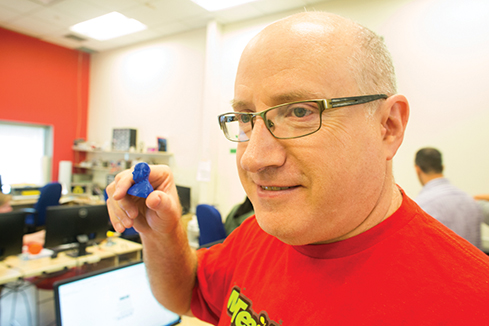

This kind of sophisticated rapid prototyping is changing medicine and the face of small business. But if you ask Liz Whitewolf, she’ll tell you your average Jane comes to the lab for the 3D printer, but stays for the laser cutter. “It’s not as sexy, but it’s precise, fast, and you can use a lot of different kinds of materials with it,” says Whitewolf. “People fall in love with it.” At boot camp, Michele Thomas, a STEM specialist for fifth and sixth grade at Kiski Area Upper Elementary School, is learning this firsthand. Having recently received a grant to buy some of its own making equipment, the district empowered Thomas with deciding what equipment to buy and how to arrange it. So she’s giving Fab Lab a test drive. Upon designing and printing a small plastic doorstop for her classroom on the 3D printer, she’s equally amazed and cautious. “If printing something this small takes about an hour, you have to figure that into class assignments,” she says. “It’s a must have, but you have to think more closely about how it might be most effectively worked into projects.” She snaps a quick picture of her completed parallel circuit: a star all aglow. “I just sent it to my principal,” she says. “This is my first time using any of these tools. It’s good to know you can pick it up fast.” To give the 3D printer a go, Steve Weiss picks up a quick lesson he thinks will be a fun motivator for his middle school science students. While seated in a wheeled desk chair, he uses his feet to slowly spin himself 360 degrees while a fellow teacher uses a wand to scan him from the shoulders up. An hour and 29 minutes later, a 2-by-2-inch blue plastic bust—a 3D selfie—appears. “If you’re student of the month, you get to print your own likeness,” he says with a smirk. “Somehow I think they’ll like this.”

|

|||||||||||

Book Smart · Imperfectly Modern · Divine Provenance · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Steve Tonsor · Artistic License: Drawing Hopper · About Town: Move Over, T. rex · First Person · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |