Fall 2015

Fall 2015|

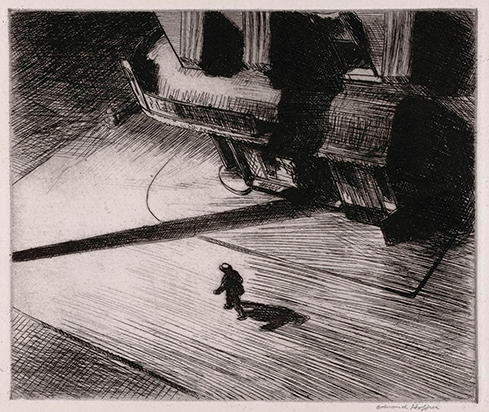

Drawing Hopper

Carnegie Museum of Art showcases its works by Edward Hopper, tracing the creative process of the draftsman turned iconic painter.

Say the name Edward Hopper to just about any art enthusiast, and it’s almost possible to see the image racing into that person’s frontal cortex: A painting of a brightly lit diner at night, a lone three customers at the counter. The vantage point is from the outside looking in through a long expanse of windows; the backdrop an empty city street. Nighthawks, as the iconic American work is titled, is shorthand for Hopper. Despite being one of the best-known— and best-loved—American painters of the 20th century, Hopper produced far more drawings, etchings, and watercolors over the course of his lifetime than oil paintings. CMOA Collects Edward Hopper, an exhibition on view at Carnegie Museum of Art through October 26, explores that depth by including art from every medium. With 22 works total, the show is an intimate meet and greet with the artist, says organizer Akemi May, the museum’s assistant curator of fine arts and decorative arts and design. “Seeing him in every medium really helps you understand who Hopper is and what he was able to accomplish in his paintings.”

- AKEMI MAY, EXHIBITION CURATOR“It’s very digestible; it’s a small but memorable bite,” May says. “An amuse-bouche.” That taste allows viewers to get at the marrow of Hopper’s career, which resides in the meticulous, iterative, off-canvas works that laid the foundation for his iconic paintings. “Seeing him in every medium really helps you understand who Hopper is and what he was able to accomplish in his paintings,” says May. Known for his New England landscapes, Hopper was born into a middle-class family in Nyack, New York, in the waning years of the 19th century. Though he came of age as Modernism did, Hopper never fully embraced the era’s aesthetic. An anecdote from one of his three trips to Europe between 1906 and 1910 illuminates the artist’s almost obstinate self-determined style. At the time, Paris seethed with the mad turmoil of the new century, with the demise of Victorian mores, the speed of travel, and the quicksilver of new ideas; it fed the intellectual hunger, imagination, and irrepressible carryings-on of everyone from Gertrude Stein to F. Scott Fitzgerald to Picasso. But Hopper, when asked whom he had met there, responded, “Nobody. I’d heard of Gertrude Stein, but I don’t remember having heard of Picasso at all. Paris had no great or immediate impact on me.” It wasn’t that Hopper was immune to the influence of other artists—the work of Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet informed his painting. When he took up printmaking, largely teaching himself, he looked to people whose work he admired, which is why Carnegie Museum of Art’s show includes five non-Hopper works from its collection by Martin Lewis, Charles Meryon, Rembrandt, and John Sloan. The consistent theme, however, is that Hopper could make use of a technique or an idea without emulating it. “He always stayed a representational artist,” says May. “There are these abstract and geometric qualities to the works. He’s knowledgeable of everything that’s going on but decides to stay as far away from it as possible.” Hopper’s ability to hold his own artistic course speaks to his perseverance, a quality that helped him ride out the intermittent success of the first half of his career. After selling his first painting, Carnegie Museum of Art’s Sailing, at the first Armory show in 1913, Hopper didn’t sell another painting for a decade. “In order to sustain himself, Hopper was a commercial illustrator,” explains May. “Though creating art for others wasn’t entirely satisfying. For his own artistic outlet he was able to channel his energy primarily into etching.” May is most excited to showcase 11 of these etchings, all owned by the museum and several of which have never before been on view. Looking at them feels like reading the rough draft of a movie script. “He struggled in early years with composition,” says May. “In etchings he was able to really explore these ideas that he had with a freer hand, exploring compositions and themes that you see later in paintings. They really are the seeds for ideas that are fully realized later on.” Hopper—like his art—was sometimes described as taciturn, standoffish. His buildings and street scenes devoid of people and studies of lone figures or figures that don’t interact with one another have led critics to ascribe feelings like loneliness and social isolation to his work. But May and other art historians see something else in those seemingly empty expanses: Hopper is making room for people. “He likes to leave it up to the viewers to really come to their own conclusions,” she says. As an example, May points to an etching titled The Lonely House. In it, a two-story building dwarfs a pair of children at play. It could be the architectural version of The Giving Tree. “Even buildings he’s able to treat as something very tender,” May says. “He gives them a personality.” That empathy for his subjects creates a covenant with the viewer that attracted Pittsburgh collectors Rebecca and James Beal to Hopper’s work. The couple, who lived in a modest apartment within walking distance of Carnegie Museum of Art, purchased some of the artist’s most impressive watercolors and oils, five of which they gave to the museum, three in their will. In all, the Beals donated more than 250 objects to the museum. There’s no doubt they’d be thrilled that the show features all 17 works by Hopper in the museum’s collection, shown together for the first time. In an essay on the Beal Collection of American Art, art historian Henry Adams notes that what attracted the Beals to the art they purchased was “inner spiritual resonance rather than large size or strong decorative impact.” The world Hopper captured is not unlike the artist himself: full of feeling, yet understated. CMOA Collects Edward Hopper is supported in part by Jane C. Arkus.

|

Book Smart · Imperfectly Modern · Divine Provenance · The Fab (Lab) Life · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Steve Tonsor · About Town: Move Over, T. rex · First Person · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |