|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Edward R. Massery, Civic Arena Yields to the Pittsburgh Skyline, 2012, from the series Last Light, Carnegie Museum of Art, Purchase: Second Century Acquisition Fund © Ed Massery |

Imperfectly Modern

A new Heinz Architectural Center exhibition considers the highs and lows of Pittsburgh’s postwar redevelopment—and the intentional and unintentional consequences still being debated today. By the end of World War II, urban development in American cities neared a standstill. Resources had been diverted elsewhere for years. Housing stood dingy and unmaintained. Pollution poured from factories and crime increased. The problem was dire. The quality of life was deteriorating. With more than 7 million servicemen and women returning home from abroad, an opportunity offered by the GI Bill did not go unnoticed. It was possible for veterans to obtain low-interest, zero-down-payment loans for home ownership. The most desirable terms only applied to new homes, few of which existed in cities, so the decision was made promptly and en masse. Families—mostly white and middle class—pulled anchors, signed mortgages, and packed their cars for the suburbs. The exodus from cities, aided by the expansion of commuter highways, left urban populations and their contributing tax bases shriveled, exacerbating the problem. The national response came in 1949 with the Federal Housing Act, which allocated landmark sums to help cities rehabilitate areas deemed as slums. Pittsburgh, then considered among the dirtiest and most economically depressed cities in the country, became an early adopter of a process called urban renewal, an aggressive approach to tearing down dilapidated structures and remaking the urban landscape on a grand scale. Out with the old and in with the new. The concept offered promise, a clean slate, a shining solution to a pressing problem.

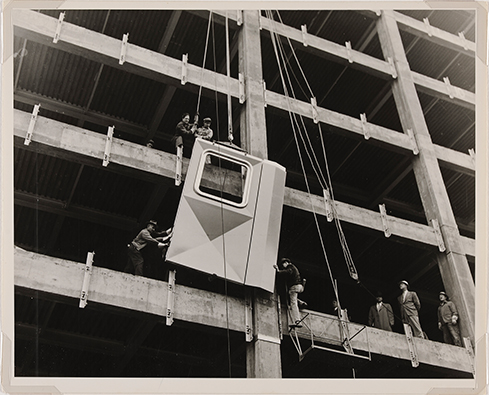

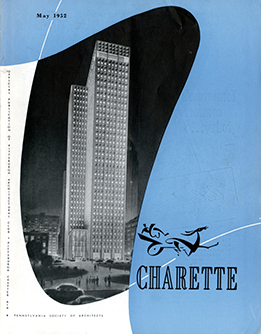

A new exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Art’s Heinz Architectural Center titled HACLab Pittsburgh: Imagining the Modern, curated with architects-in-residence over,under and running September 12, 2015–May 2, 2016, examines postwar architecture and urbanization in Pittsburgh from 1945 to1975. Using photography, documentary film, and news clippings, the show offers nuanced insight into the stellar moments, sweeping mistakes, and fraught debates that defined the era in Pittsburgh and similar Rust-Belt cities. It showcases radical proposals for Downtown’s Gateway Center, the Lower Hill, the North Side’s Allegheny Center, East Liberty, and Oakland— some enacted and some not. In the exhibition’s main gallery it envisions what might still be constructed. “Pittsburgh was presented in the national media as an exemplar for urban development in the postwar period,” says Raymund Ryan, curator of architecture at Carnegie Museum of Art. “It was a model for how a city might evolve.” A MODEL, BUT OF WHAT?In 1939 the Pittsburgh Regional Planning Association hired a consultant named Robert Moses to solve problems related to traffic congestion around the Golden Triangle. Famous for his public works accomplishments in New York—he was known as New York’s “master builder”— Moses was a divisive figure. He was credited with creating the template for the new American city: it was an escape from the dirt and chaos of the Victorian and home to skyscrapers, highways, and pristine parkland settings. To do so, he used whatever means necessary and was criticized for displacing people from their homes. “I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without removing people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs,” Moses said, according to his New York Times obituary. “There was a very strong sense of corporate identity. It’s what you might think of as Mad Men territory, this glamorous notion of what it meant to work for a large company.”

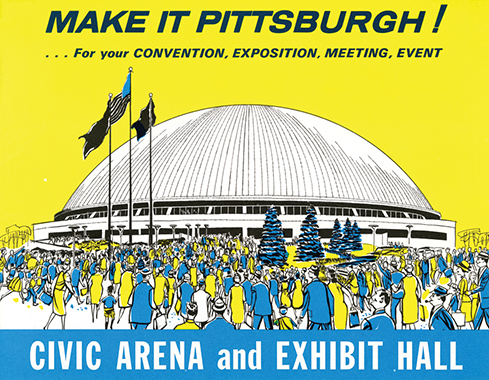

- RAYMUND RYAN, CURATOR OF ARCHITECTURE AT CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF ARTHis proposal for the Point was titled the “Arterial Plan for Pittsburgh” and, created in three months, it was comprehensive. The Pittsburgh Press published his recommendations under the headline “Highways to Suburban Areas.” Based on roadway systems adopted in New York City, the plan led to the Penn-Lincoln Parkway and Crosstown Boulevard and to the construction of Point State Park. “The Moses Plan is really forward-looking and not unabashed in its aim to reinvent the city,” says Chris Grimley, a partner at over,under. “It sets the stage for the postwar Renaissance in terms of its vision and its scope.” The reinvention of Downtown continued with the rise of Gateway Center in the 1950s. Skyscrapers sang an ode to Pittsburgh corporations. “There was a very strong sense of corporate identity,” says Ryan. “It’s what you might think of as Mad Men territory, this glamorous notion of what it meant to work for a large company. “And you might think of Moses as a very top-down planner. This idea of planning on a very big scale, as opposed to grassroots or neighborhood planning, was big in the 1950s.” But by the 1970s, these ideas fell into disrepute. “They seemed to be completely denying history and the grain of existing neighborhoods,” says Ryan. In 1962, Jane Jacobs, a grassroots planner and strong critic of Moses, spent a week consulting in the city at the invitation of the University of Pittsburgh. She had just published her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities and was known for leading neighborhood campaigns that opposed large-scale destruction of New York’s original Greenwich Village neighborhood. Upon her arrival at Pittsburgh International Airport, itself a result of the city’s postwar Renaissance, she received a driving tour of renewal projects around town, including the Lower Hill, which had recently been razed to construct the Civic Arena. At the conclusion of the tour she made a statement to the press: “Pittsburgh is being rebuilt by city haters.” Throughout the week, she defended her claim. Jacobs sat on panels insisting that no independently hired planner was capable of doing the work effectively, that only residents of a community knew it well enough to control its layout, and that plans to speed renewal by tearing down buildings were shortsighted and lazy. According to an article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, her rhetoric was so strong it prompted an executive on the Greater Pittsburgh Board of Realtors to throw up his hands and say: “If you followed her program in toto, you would do nothing!” This article and others pulled from local and international press are exhibited in HACLab Pittsburgh and demonstrate how the city became part of a national conversation. “We’re trying to unravel this back and forth between being conscious of what already exists and the social and psychological importance of neighborhood, and at the same time being aware that some of the conditions people were living in were pretty dire,” says Ryan. STILL GRAPPLINGHACLab Pittsburgh: Imagining the Modern is the first in a new series of shows at the Heinz Architectural Center, each of which will partner with separate architects-in-residence to explore regional architecture in dynamic ways. “It’s all a bit experimental,” says Ryan. “With the labs, we’re trying to make exhibitions that are more like works in progress. They’re more about engagement and process than, let’s say, a mute display of beautiful objects.”

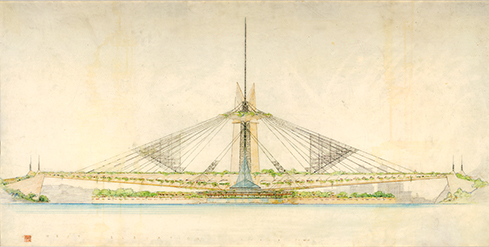

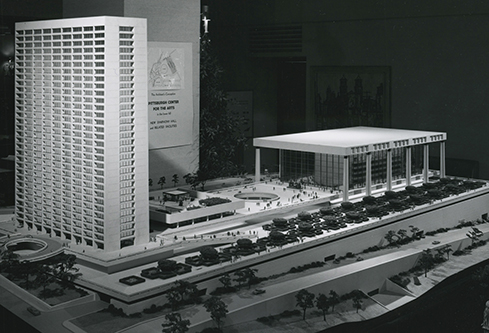

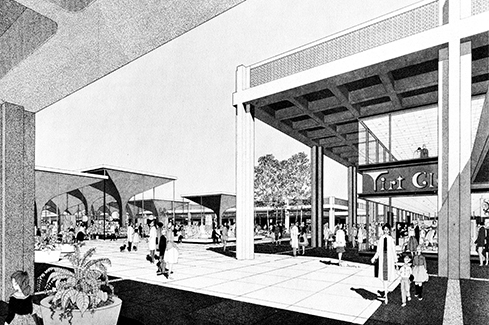

For its part, the first HACLab opens with an instructional area that organizers refer to as “Urban Renewal 101,” and then quickly moves into a more speculative space, highlighting plans that were proposed for Pittsburgh but never came to be. There were two Frank Lloyd Wright proposals for the Point, one of which featured an immense circular structure a quarter mile wide. “If it had been built, there would have been plenty of science fiction and dystopian future films being set there,” says Grimley. A symphony hall and center for the arts for the Hill District would have rivaled New York’s Lincoln Center. An aggressive expansion of the University of Pittsburgh in Panther Hollow proposed new research and office space, punctuated by gardens, pools, and a helipad. A series of recommended pedestrian malls in East Liberty contributed to a national discussion about the importance of the Main Street and small-scale commerce as the heart of a community.

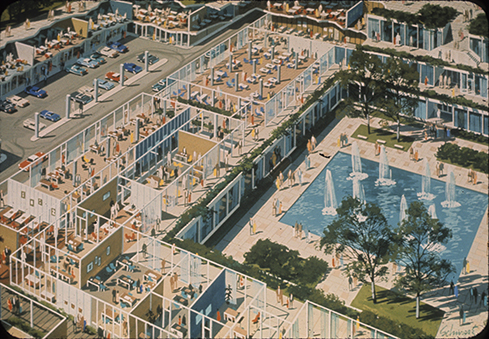

The largest gallery in the show perhaps best embodies the experimental spirit of the HACLab series. Looking to the future, it will host a semester-long studio during which students at Carnegie Mellon’s School of Architecture will rethink Allegheny Center, posting their evolving plans on museum walls for the public to ponder and revisit again and again. The lab will be taught by el Samahy, who splits his time between over,under and teaching at the university. Allegheny Center emerged as an obvious choice for such a study early on in the exhibition’s planning. It’s a project with a fraught urban renewal story that continues today. In the early 1960s, in response to high crime, poor living conditions, and a 24 percent decline in the population of the North Side between 1950 and 1960, the city razed a total of 518 buildings to accommodate new office buildings, apartment complexes, and a shopping mall on a pedestrian street encircled by a multi-lane road designed for easy access from a new highway system. Allegheny Center would “become as important to the future of the North Side as Gateway Center was in the rebirth of the Downtown,” predicted Mayor Joseph Barr, according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “The call to remove Allegheny Center because it’s ugly or because it doesn’t work is effectively the same kind of rhetoric that was used to create it.”

- RAMI EL SAMAHY, AN ASSOCIATE TEACHING PROFESSOR AT CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY’S SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND A PRINCIPAL AT OVER,UNDERYet despite some initial success, the plan proved ill-fated. The traffic circle cut off most of the commercial space from pedestrian reach of the surrounding neighborhoods. Despite a new road network and parking garage, it could not compete with the ease of vehicular access offered by suburban shopping centers. As a result, most of the mall’s 75 stores were replaced by business offices that did not rely on foot traffic. Soon the empty pedestrian zones created pockets for crime, and a population formerly estimated to increase from 2,000 to 4,500 hovered near 1,800. Allegheny Center, once renewed, is again up for redevelopment.

Shortly after the lab set its focus on Allegheny Center, a New York developer announced plans to redesign the mall into a technology hub. “It’s exciting and kind of serendipitous that the city has found a buyer for the area,” says el Samahy. “It’s more speculative where the students want to take it; that’s what school is for.” Students can choose to reinstall buildings that once stood or clear the way for something altogether new. For his part, el Samahy recognizes a pattern in thinking.

“The call to remove Allegheny Center because it’s ugly or because it doesn’t work is effectively the same kind of rhetoric that was used to create it,” he says. It’s not that every building on the site should be sacrosanct, he suggests. “The big issue is wholesale removal of what exists today to replicate some moment in the past. It would only be repetition of the mistakes that were already made.

“The only real way forward is a hybrid that celebrates the pre-modern era and also the modern, which is really one of Pittsburgh’s most important eras if you think about it.”

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Book Smart · Divine Provenance · The Fab (Lab) Life · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Steve Tonsor · Artistic License: Drawing Hopper · About Town: Move Over, T. rex · First Person · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |