|

||||||||||||||||||

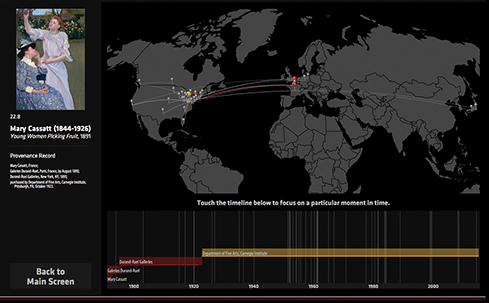

An interactive in-gallery touchscreen allows visitors to view both the history of ownership and the exhibition history of 20 of the museum’s most popular Impressionist paintings. |

Divine Provenance

With art sleuths and a powerful new software program named for Andrew Carnegie’s housekeeper, Carnegie Museum of Art is leading the field in not just organizing, but visualizing for the public the fascinating stories of its collections. In 1890, Vincent van Gogh quieted his inner demons by painting wheat fields in Auvers-sur-Oise, a small French village northwest of Paris. His dense brushstrokes formed a patchwork quilt of yellow and green wheat and wildflowers, beneath blue skies and puffy white clouds. But the calm he felt painting the landscape was short-lived. A few days later, Van Gogh shot himself not far from the pasture that inspired him.

Seventy-eight years later, Wheat Fields after the Rain (The Plain of Auvers) arrived at Carnegie Museum of Art, acquired through the generosity of Pittsburgh philanthropists, the Sarah Mellon Scaife family. How did this Impressionist masterpiece get from the European countryside to a museum wall in Pittsburgh? And how do visitors know that Wheat Fields is the real deal and not a reproduction? Enter the Art Tracks: Provenance Visualization Project, a pioneering initiative of Carnegie Museum of Art’s digital media lab, which is giving the museum-going public easy access to these answers, and more. Visitors to the Scaife Galleries can now trace both the history of ownership and the exhibition history of 20 of the museum’s most popular Impressionist paintings, including Wheat Fields. Traditionally, provenance—research of the history of ownership and custody of art—has been presented as a dry and static list of names, dates, relationships, and locations. Art Tracks, made possible in part by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), brings to life the often fascinating historical narratives of artworks. Just as images on a canvas tell a story, so does the history of how the work changed hands. “Paintings don’t just sit on walls,” says Louise Lippincott, Carnegie Museum of Art’s curator of fine arts. “They have these interesting and important stories. This project is a fun, creative way to share those stories with the public.” Eye-opening discoveriesVisitors can learn, for example, that Wheat Fields once hung inside the home of Harry Graf Kessler, a German aristocrat and Renaissance man of the early 20th century. “He was famous for knowing everyone who mattered, from artists to musicians to writers to politicians to actresses,” Lippincott says. “His little black book would have been a treasure.” A patron of the arts, Kessler had an impeccable discernment for the art of the early 20th century. “Kessler was an early collector of Van Gogh before Van Gogh became the household name he is today,” explains Costas G. Karakatsanis, the museum’s provenance researcher. The fact that Kessler owned Wheat Fields adds to the prestige of one of the most famous paintings in the world. “Van Gogh is a household name and you’ll find Wheat Fields on coffee mugs,” Lippincott says. “That’s not the same kind of fame as being part of a collection formed by one of the best eyes in the 20th century. It puts our painting in a very important place in a very important moment in modern art.” Though the museum’s curators had known that Kessler owned the painting by 1901 to at least 1929, Karakatsanis kept unearthing new facts that required him to update, and enrich, its provenance several times. “It’s very exciting to see one of ‘your’ paintings in a famous place at a famous time in art history.”

- COSTAS G. KARAKATSANIS, CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF ART PROVENANCE RESEARCHERAs is often the case with good detective work, he found clues where he was least expecting them. While reviewing the history of another Van Gogh painting in Indianapolis, Karakatsanis stumbled upon a reference to a German publication highlighting Kessler’s collection. He tracked down the source in the Frick Art Reference Library in New York City, an unrivaled resource he visits several times a year. To his amazement, he found that it included a black-and-white photograph taken in 1910 of Wheat Fields hanging in Kessler’s library in Weimar. “It’s very exciting to see one of ‘your’ paintings in a famous place at a famous time in art history,” says Karakatsanis. When Kessler owned it, Wheat Fields hung in a simple 20th-century frame with classical lines, more suitable, Lippincott notes, than the ornate 18th-century frame with scrolls and carvings that holds it today. In fact, she hopes to raise funds to commission a new frame similar to the one in the vintage photograph. Following the breadcrumbsOther paintings in the museum’s collection have had an extensive exhibition history since joining the Carnegie Museum collection. Consider Mary Cassatt’s Young Women Picking Fruit, which has an airtight provenance. A French dealer bought it before selling it to Carnegie Museum of Art in 1922. “There is a letter from Cassatt saying how happy she was that the Carnegie bought it,” Karakatsanis says. “You can’t get any better than that.” Since 1922, the painting has traveled to museums around the globe, a fact that will soon be illustrated in the galleries by a series of gray lines on a map zooming to Tokyo, Berlin, Grand Rapids, Michigan, and plenty of points in between. “We joke that if you add up all the miles it traveled and divide it by the number of years, you could come up with a mph,” Lippincott says, noting that this kind of easy-to-digest display signals to visitors that this particular work is not only precious, but in demand. Provenance research is a lot like a puzzle, and women taking their husband’s names can complicate the process of connecting the pieces. Museum records show, for instance, that Simon Vouet’s The Toilet of Venus changed hands from Mary Cassatt to her brother to Mrs. Horace Binney Hare. Tracey Berg-Fulton, the museum’s collections database associate whose job is to sift through and translate reams of museum records, was perusing the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s online collections database when she stumbled upon a footnote. Mrs. Horace Binney Hare, it turns out, was Ellen Mary Cassatt, the artist’s niece. “Familial connection makes that story more interesting,” Berg-Fulton explains. “The work went from Mary Cassatt to her brother to his daughter.” It’s all information she soon discovered was already tucked away in museum files, but that’s certainly not always the case. Sometimes a breakthrough can come after reading tiny scribbles in the margins of centuries-old art catalogues. “Some are great,” she says. “They look like a teenager texting with three exclamation points after it. This is something that translates across the centuries.” But wading through centuries-old resources also presents challenges. Sometimes records will only mention the title and the painter of a work, and not its dimensions. But even knowing the dimensions of a painting is not always a surefire way of determining whether the painting described in a catalogue is the same one hanging in your museum. Titles, especially, are famously unreliable as they sometimes change many times, often due to documentation errors, over the history of the artwork. There’s often multiple languages to decipher, as well. “Two hundred-year-old handwriting in Dutch is not the easiest thing to read,” Berg-Fulton says, laughing. Weeks of slogging through library records and online databases can lead to nothing, followed by the thrill of a great find. As Berg-Fulton put it, “Every once in a while you find this little breadcrumb, that loose string dangling you can pull on.”

Art museums have been doing this kind of sleuthing for years. A concerted, field-wide effort has been made in the last decade to investigate the World War II-era provenance of European paintings—works that were acquired after 1932 and created before 1946—due to looting during the Nazi era. Public awareness of the issue was heightened by the 2014 George Clooney movie The Monuments Men, which tells the story of art scholars, historians, and other experts who risked their lives to retrieve masterpieces stolen by Nazi troops; and again this year with the film Woman in Gold, which traces the Nazi-era theft of Gustav Klimt’s gold-leaf portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer and its 2006 return to the Bloch-Bauer heirs. Museums want to make sure what’s in their collections is legally theirs. “It’s like a title search,” Lippincott says, noting that the museum’s research on its own works from that era is ongoing. What makes Art Tracks unique is how it’s using technology to give order and meaning to the heaping paper and digital trails attached to each work of art—from condition reports and loan agreements to scholarly articles, wills, and even the old-fashioned card catalog files. “A lot of really important details are buried in databases and footnotes,” Berg-Fulton affirms. “We’re teasing them out in meaningful ways.” Perhaps surprisingly, every museum has its own way of providing provenance information. With Art Tracks, Carnegie Museum of Art is leading the charge for a uniform and robust provenance language based on the American Alliance of Museums standards. By developing software to then read this language, the museum is able to generate timelines and narratives that shed new light on the objects in their collection. The process is a collaboration in the true sense of the word. Lead developer David Newbury is a self-professed computer geek who didn’t know an Impressionist painting from the work of an Old Master until a year and a half ago. Berg-Fulton, who is trained as a museum registrar, has an art history degree and is charged with translating the provenance unearthed by Karakatsanis who is a chemist by profession and worked for Bayer for 27 years before volunteering his research skills at the museum. “Tracey [Berg-Fulton] is trying to get as much story in as possible,” Newbury says. “I’m trying to get rid of the ambiguity.” It’s exactly that kind of back and forth that has helped Newbury develop software that reveals, in some cases, unbelievably rich histories of works of art. “It would have never occurred to me that it would matter if a painting were given, bought, or stolen,” says Newbury. “In the museum world, it’s incredibly important. It helps you understand the history of a given object. It’s where the stories live.”

The team identified 25 different ways a work can change hands. This ranges from acquisition, inheritance, and commission to less common avenues such as field collection for archaeological artifacts to looting from the Nazi era. The software, which took Newbury a year and a half to develop, is called Elysa and like everything else in this project it has a good story behind it. They named the program for Andrew Carnegie’s housekeeper, often known simply as Mrs. Nichol, to whom he left a sizeable pension. “Every once in a while you find this little breadcrumb, that loose string dangling you can pull on.”

- TRACEY BERG-FULTON, CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF ART’S COLLECTIONS DATABASE ASSOCIATEWith Elysa, the team has created a visual and digestible method of sharing provenance while updating it in real-time. In fact, they’re so excited about its possibilities that the team is in talks with other museums, including the Smithsonian Institution, about upgrading their data so they can use Elysa, too. “We’re in the middle of securing some significant partnerships with some major museums in the country,” Lippincott says. “We are a couple of years ahead of everyone else in the field.”

The kind of integration they aim for would allow museums to work together to identify the often interconnected past of famous collections, such as the Northbrook collection, named for the Earl of Northbrook and other family members who founded the Barings Bank, an institution so powerful that it helped finance the Louisiana Purchase. Four generations of the family bought and sold to create this famous collection of Old Masters paintings that number in the hundreds and are dispersed around the world. Through meticulous research, Karakatsanis discovered that Carnegie Museum of Art owns six of these works, given to the museum by four different donors. “Five of those are reunited in the same gallery, which is amazing for a museum our size,” Karakatsanis says. He knew that the painting Hero, Ursula, and Beatrice in Leonato's Garden (act 3, scene 1 from Much Ado About Nothing) by Reverend Matthew Williams Peters was donated to the museum by the children of Mrs. Alexander C. (Tillie) Speyer, an artist and arts supporter from Pittsburgh. But not much of the painting’s earlier history was known, including when and how Mrs. Speyer had acquired it. Only after extensive research proved that the work was part of the Northbrook collection, did he fill in the gaps of its ownership history, revealing that the work was purchased at a 1933 auction in New York, much earlier than previously thought. Karakatsanis’ research solved a mystery behind another Northbrook work, Lady Ann Fenhoulet painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1760. Lippincott had always been troubled by the poor condition of the portrait, with cracks and bubbles in a small section of the background of the painting. Karakatsanis tracked down a 19th-century catalogue of engravings of Reynolds paintings and found a note that this painting had been damaged in a fire. “Lulu’s face lit up,” he recalls. “It was the background she needed.” Lippincott then shared that information with the museum’s paintings conservator, who will be able to restore it using the proper techniques for fire damage. “Reconstructing the history of a work can be thrilling,” says Lippincott. “So is interpreting and sharing that history.”

|

|||||||||||||||||

Book Smart · Imperfectly Modern · The Fab (Lab) Life · President's Note · NewsWorthy · Face Time: Steve Tonsor · Artistic License: Drawing Hopper · About Town: Move Over, T. rex · First Person · Travel Log · The Big Picture

|

Copyright © 2017 CARNEGIE Magazine. All rights reserved. |